Troy Mansfield had barely sat down in his new lawyer’s office before his voice started cracking with emotion.

The married father of two grown sons choked back tears as he told Austin attorney Kristin Etter how he had spent two decades living with a scarlet letter for a sin he didn’t commit. He’d been cast out of homes, thrown out of his boys’ basketball games and even rejected at churches.

Clutching the hand of his soft-spoken wife, the clean-cut man with salt-and-pepper hair wept as he described how his family was forced into poverty, living off as little as $16,000 a year.

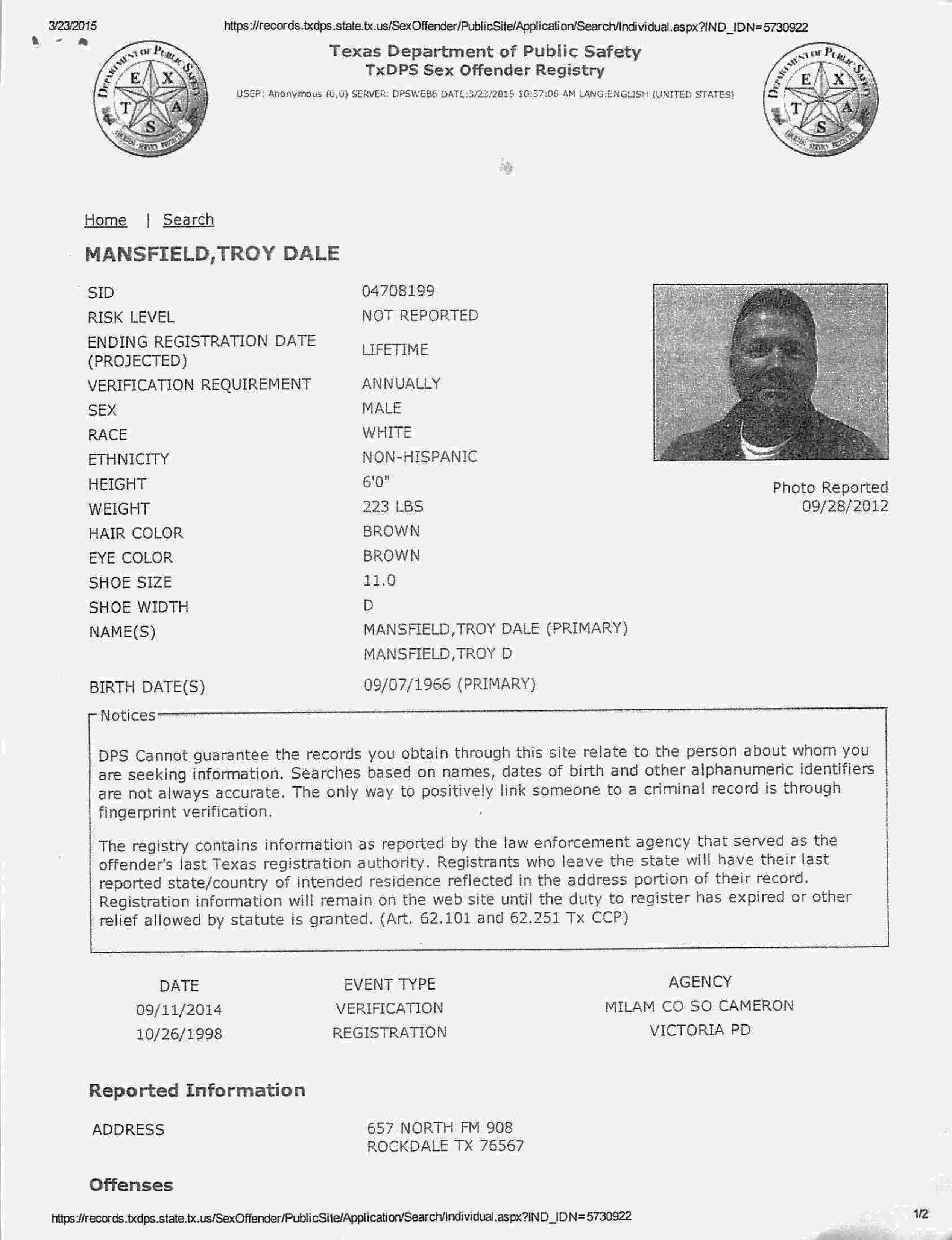

In 1993, he explained, he had been convicted in Williamson County of molesting a 4-year-old girl, forced to register on the state’s list of rapists and pedophiles. He pleaded guilty to a crime he said he could never imagine committing because police and prosecutors relentlessly badgered him and threatened to destroy his family.

As Etter listened intently and scribbled notes on a yellow legal pad during their 2014 meeting, Mansfield explained that he had learned about a new law that might finally free him from his life of shame and help him get off the registry.

“As soon as I learned there might a chance, I tried to figure out a way,” he says.

Regrettably, Etter told him, the law wouldn’t help.

But something about the 48-year-old man’s sincerity tugged at her.

“He was just very credible,” she says.

There was more than a feeling.

Etter quickly realized her new client had been convicted of molesting the girl during a dark period in Williamson County criminal justice. Ken Anderson, the former district attorney and judge, since disgraced and disbarred for concealing evidence that led to the wrongful murder conviction of Michael Morton, had overseen Mansfield’s case.

Etter couldn’t help wondering if the tearful man sitting on the other side of her desk was another victim of an agency corrupted by a lock-them-up culture that prized winning over justice.

She would soon start pondering a more alarming question: Had anyone thoroughly reviewed Anderson’s cases to ensure that more innocent people like Morton weren’t unjustly convicted?

She told Mansfield and his wife, careful not to set them up for yet another disappointment, that she would look into his case but probably wouldn’t find much.

“We won’t know until we try,” she said.

Etter began pursuing Mansfield’s 21-year-old case file, logging countless phone calls and emails to the county just north of Austin.

Six months passed before she was invited to review it in a conference room at the district attorney’s office. There, she opened a shockingly thin brown folder and saw pages of handwritten prosecutor notes from interviews with the little girl who accused Mansfield of touching her.

Scrawled in the prosecutor’s handwriting across the pages was exactly what she expected.

“She told me she doesn’t remember what happened! At one point, told me nothing happened.”

Shocking interrogation

Mansfield was 25 in 1992, living with his wife and two young sons, John and Mason, in a wood-framed rented duplex in a middle class Round Rock neighborhood. He was a manager at an auto parts store in Round Rock, in line for a promotion to regional manager. Amy, his childhood sweetheart, was a stay-at-home mother.

When a Round Rock police officer called Mansfield and asked him to come to the station, he figured he knew why. A few weeks earlier, he had been arrested with a small amount of marijuana.

Mansfield sometimes smoked pot to dull the pain of a back injury he suffered while loading a B-1 bomber on a flight line in the U.S. Air Force. He had served in the military from 1986 to 1988, when his career was sidelined because of the injury. He eventually moved to Austin, then to Round Rock, so he would be closer to work.

The officer, he thought, probably wanted to know where Mansfield had gotten the pot. He agreed to meet with Detective Dan LeMay that August afternoon.

Inside the windowless interrogation room, though, the conversation took a shocking turn, according to Mansfield and the police report Etter found in the file.

LeMay informed him that a 4-year-old girl, who lived in a neighboring duplex, had told her parents that Mansfield had tickled her and fondled her through her underwear.

Mansfield was dumbfounded. The girl and his 4-year-old son had played at his home just a few days earlier. The children roughhoused on the two beds in his son’s room, hiding under the covers while Mansfield tossed them from bed to bed. He hadn’t inappropriately touched her, he told the officers, as he racked his brain to think of how or why the little girl could have said such a thing.

But that didn’t satisfy LeMay.

The officer badgered Mansfield for hours, trying to force him to admit he had molested the girl. LeMay told Mansfield, who was visibly shaken by the alarming turn of events, that he could leave anytime. But the officer promised that if Mansfield left, he would make sure Child Protective Services took his children.

At one point, LeMay, who did not return messages seeking comment, told Mansfield that he could admit to fondling the girl, go next door to a mental health facility (Mansfield didn’t know it was fictitious) and bring back a receipt for an $80 therapy session for “child molesters.” In exchange, the detective offered to drop his entire investigation.

For hours, Mansfield went back and forth with the officers. Over and over, he insisted on his innocence. But the officers’ dogged insistence and increasingly frightening threats made it clear the only way he could leave was by admitting to the crime.

Emotionally exhausted and terrified that police would break apart his family, Mansfield caved after several hours, admitting he’d touched the girl.

Mansfield says he felt tricked by police, but he and his family had faith in the justice system.

“I thought, ‘Surely this is going to work out — there is no way that this can go any further than it is,’ ” Mansfield says.

The family hired a lawyer to make sure the investigation ended. But the lawyer, Stephen Cihal, who years later would be disciplined by the State Bar multiple times and did not return calls seeking comment, relayed messages from prosecutors that detectives had proof of the crime. They claimed to have a videotaped interview with the girl and a corroborating medical report of her injuries.

Over the next 13 months, Mansfield’s case was set for trial six times. Prosecutors offered a series of plea deals — one would have required him to serve 10 years in prison. They told him if he went to trial, they would ask the jury for a 99-year prison sentence — the maximum for a charge of sexual assault of a child.

Prosecutors’ final offer came the night before jury selection was set to begin in September 1993. It would require Mansfield to plead guilty to indecency with a child. He would serve 120 days in jail, spend 10 years on probation and register as a sex offender for 10 years on a database that only law enforcement would see.

Mansfield hated the idea of pleading guilty to an offense he swore he didn’t commit. But he worried that the agreement was his last hope of remaining with his family.

On Sept. 13, 1993, he signed it.

“What do you do when you are 25 years old and a county like Williamson County comes after you and you don’t have any money?” he says. “All I was thinking was, ‘I’ve got to stay home. I’ve got to take care of my wife. I have to take care of my children. I have to stay home.’ ”

‘You’ve got to leave’

Despite the state’s promise to punish him for only 10 years, Mansfield was branded a sex offender for more than two decades.

After the conviction, he and his family moved to Victoria so Amy could care for her mother, who was dying of cancer.

Mansfield applied for job after job. But he had to disclose on applications that he was both a convicted felon and a registered sex offender. No one hired him.

To survive, the family started a janitorial business in his wife’s name. Slowly, they built a clientele.

Just as the family was building a normal life, it was shattered again.

In 1997, a change in state law undid prosecutors’ promise that Mansfield would only be on the sex offender registry for 10 years. Lawmakers decided that those convicted of a sex crime after 1970 had to register forever, no matter what their plea agreements say.

A couple of years later, the registry became publicly available online. Anyone, including their clients, could see Mansfield’s photo, where he lived and the crime for which he was convicted.

Each time a client quit using the business after seeing his mug shot, Mansfield spiraled deeper into shame.

A neighbor and golf buddy threatened to picket his home in Victoria after learning he was a convicted sex offender. The Mansfields quickly packed and left their rental house.

They lived for a short time in a home they rented from a client in Victoria before moving back to Williamson County in January 1999. They lived in an RV park outside Georgetown for almost a year before, with their earnings from a handful of cleaning clients, buying a small piece of land outside Rockdale in Milam County.

There, the family attended a nondenominational church, where Mansfield sometimes preached about forgiveness. Then suddenly, church leaders demanded that the family leave.

“They came in that Sunday; they said, ‘We want y’all to get out,’ ” Mansfield says. “‘You haven’t done anything wrong, we don’t have a problem with you, but public opinion is killing us, and you’ve got to leave.’”

In 2013, 20 years after the conviction, a friend suggested that Mansfield hire a lawyer to see whether a new law might help him get off the sex offender list.

Mansfield came across Etter in an internet search. She had experience helping convicted sex offenders get their names removed from the registry, so he called to set up an appointment.

“I didn’t know anything about what had just gone on in Williamson County” with Michael Morton’s exoneration, he says. “I just wanted to see if there was a way to get off the registry.”

Conviction quietly undone

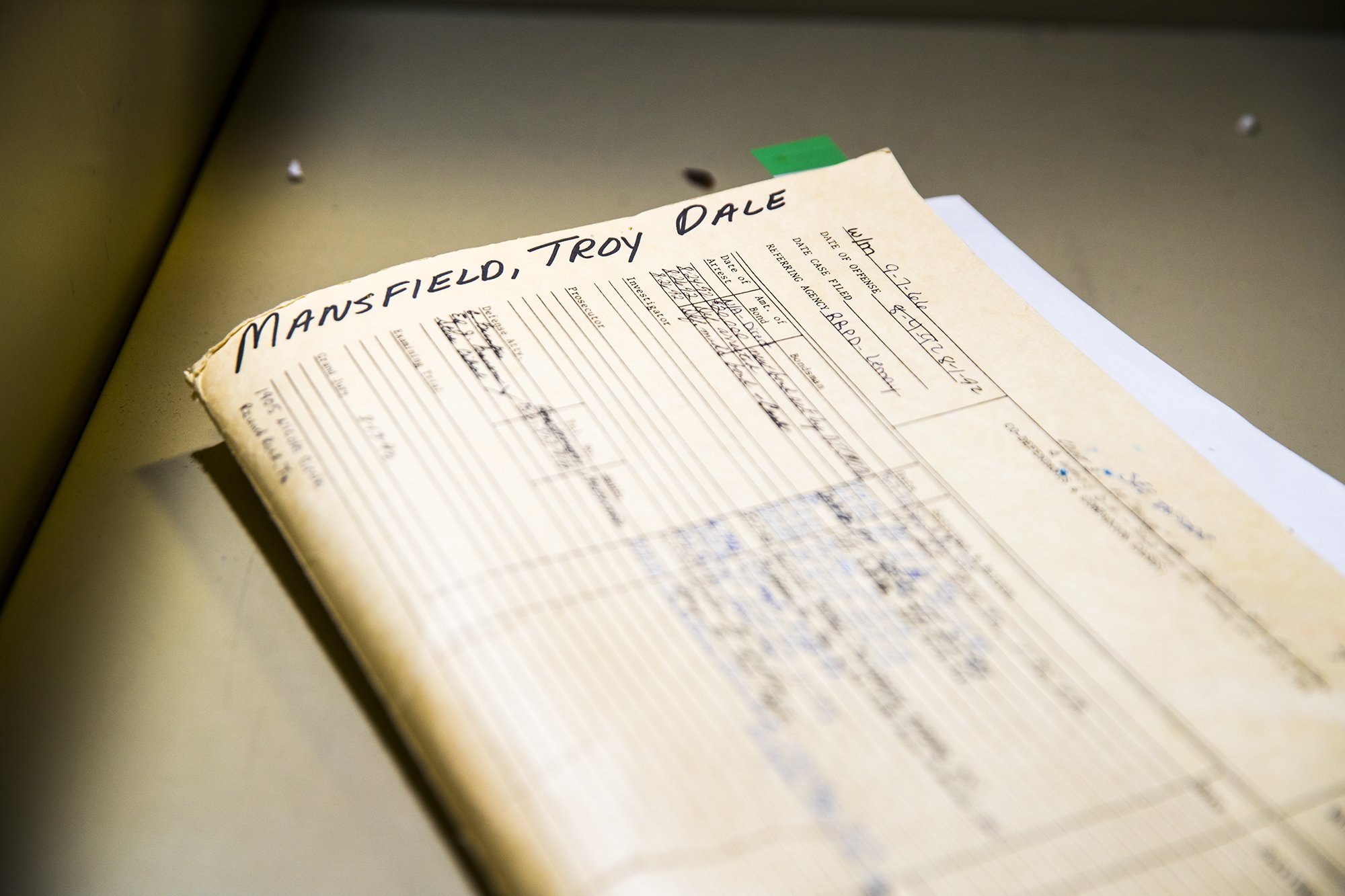

Etter thought it was odd when the district attorney’s second-in-command called her in the fall of 2014 for a meeting to discuss Mansfield’s file. Six months after she had asked for it, workers had finally found it in a warehouse.

As she drove to the courthouse, what happened to Michael Morton, whose wrongful conviction had sparked widespread outrage over criminal justice corruption, was fresh on her mind.

By then, courts had determined that Anderson, the county’s district attorney from 1985 to 2001, knowingly withheld evidence of Morton’s innocence from defense lawyers. More than two decades after he was convicted of his wife’s murder, Morton’s appellate lawyers discovered prosecutors had hid critical information that pointed to his innocence. During their fight with prosecutors over obtaining DNA evidence that eventually proved Morton’s innocence and led to the real killer, the DA’s office was forced to open its files. Morton’s lawyers discovered that his then-3-year-old son had told his grandmother, who told police, that he had seen a “monster” attack his mother while his father was away.

Anderson was charged with criminal evidence tampering in Morton’s case, served 10 days in jail and, along with being disbarred, was rebuked by the state Supreme Court: “This court cannot think of a more intentionally harmful act than a prosecutor's conscious choice to hide mitigating evidence so as to create an uneven playing field for a defendant.”

Etter thought about Anderson’s “closed file” policy and wondered what she might find in Mansfield’s file that had been gathering dust since 1993. Even though prosecutors had a constitutional duty to give defendants favorable evidence, prosecutors in the Williamson County office had wide latitude in their decisions about how and when to turn over evidence.

When Etter arrived, First Assistant District Attorney Mark Brunner explained that he and then-District Attorney Jana Duty were alarmed by what they had discovered in Mansfield’s file.

Brunner told her that it was a good thing her client had not gone to prison. Then he pointed out the handwritten notes.

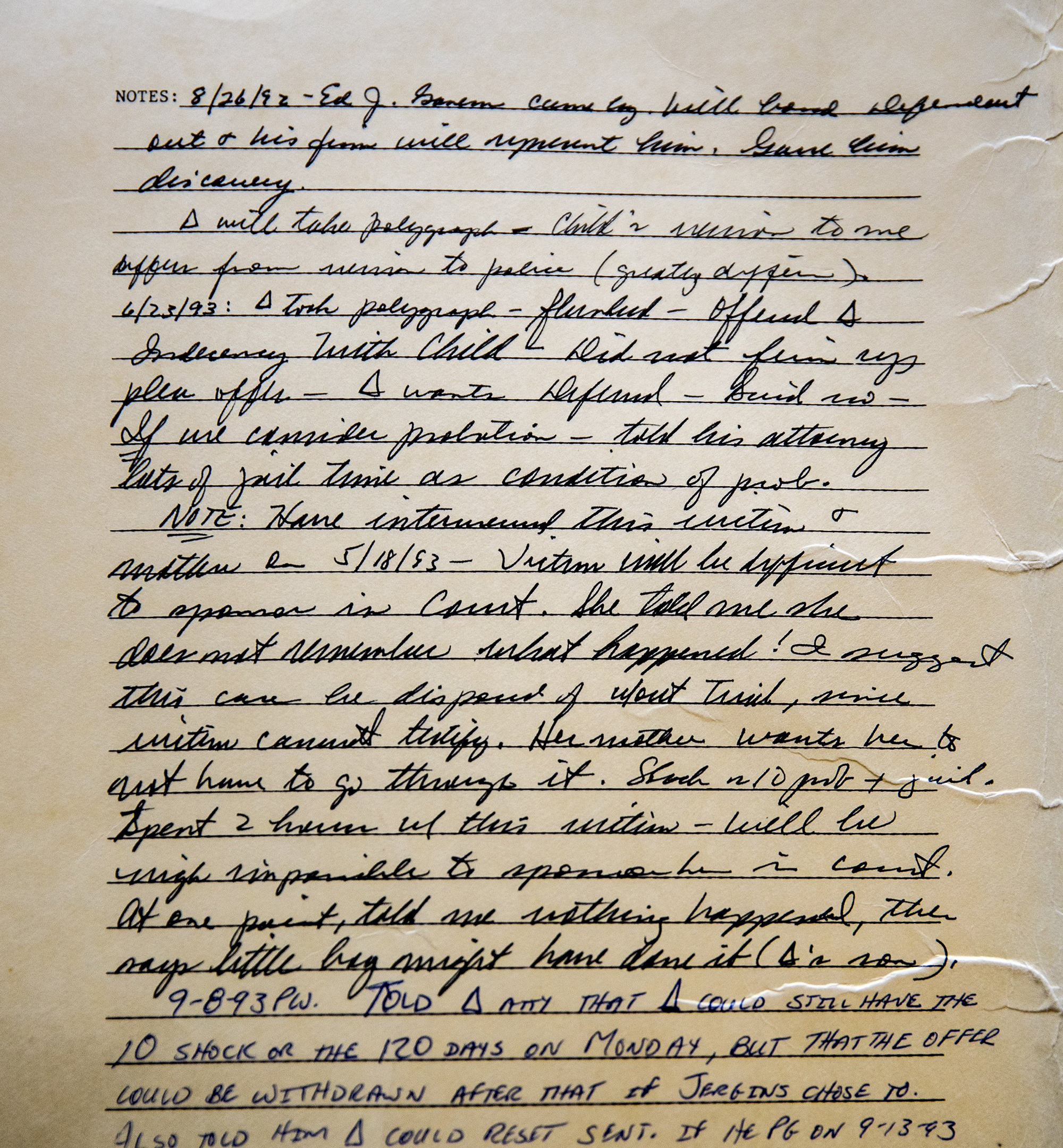

The first notation was written within three weeks of the girl’s allegation. The August 1992 note showed that prosecutors wondered about the veracity of her statements.

“Mansfield’s son under blanket with (girl). Could he have put his (little boy’s) finger in her?”

“Little kids don’t lie. Either (girl) was coached or she has been molested earlier and the accidental touching reminded her.”

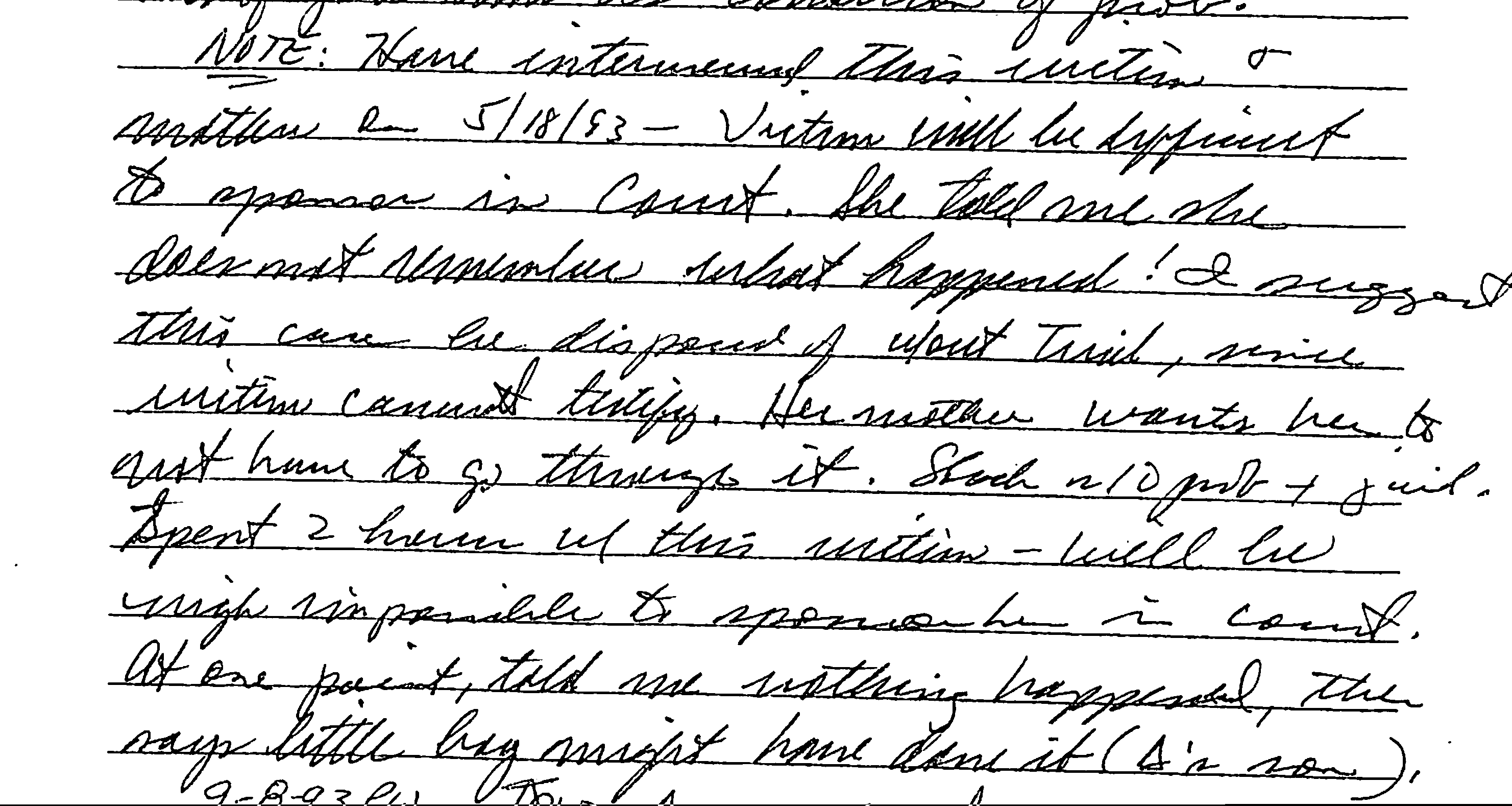

Then Etter saw another prosecutor’s notation — made just weeks after the girl’s outcry — that left her in disbelief: “Child’s version to me differs from version to police (greatly differs).”

She flipped to the next page, and suddenly the prosecutors’ entire case against her client unraveled. In different handwriting, another prosecutor expressed grave doubt about the case and whether the girl could be deemed credible enough to testify.

“NOTE: Home interviewed this victim on 5/18/1993 — victim will be difficult to sponsor in court. She told me she doesn’t remember what happened! I suggest this case be disposed of w/out trial since victim cannot testify.”

The entry concluded, “At one point, told me nothing happened then says the little boy might have done it.”

Etter called the Mansfields the minute she returned to her car.

“Amy and I just wept like babies that day, thinking, ‘Is this the beginning of the end of this nightmare that we’ve been through?’ ” Mansfield says.

Over the next several months, Etter and prosecutors crafted a joint request to have the conviction overturned, an agreement confirming that Mansfield’s due process rights were violated and that he was forced into a plea.

On Friday, Jan. 22, 2016, the Mansfields sat nervously in a Williamson County courtroom, while Etter and a prosecutor approached state District Judge Doug Shaver. The judge granted the dismissal request, taking only minutes to quietly undo a conviction that had brought Mansfield years of heartache.

“There was no article about it, nobody interviewing me, nothing from the county that ‘I’m so sorry that it happened,’ ” Mansfield says. “This devastating thing that took my life has all of the sudden disappeared.”

No thorough review of cases

The Mansfields celebrated quietly. They had no money for even a fancy dinner.

But in the weeks that followed, Mansfield felt a new freedom. By then, the couple’s sons were grown and out of the house, and they soon moved to Gonzales to be near Troy’s parents.

“When I take my dog for a walk, I can do that without neighbors looking at me and shaking their head or taking their children inside,” he says.

He’s not vengeful toward the prosecutors who ruined his life, but Mansfield says he believes they should be held accountable.

He typed out complaints to the State Bar of Texas in late 2015. He accused Paul Womack, who went on to serve for 20 years as one of nine judges on the state’s highest criminal court, and former assistant District Attorney Michael Jergins, who by then was a Williamson County felony judge, of hiding evidence.

Because Anderson, who could not be reached for comment, was already disbarred, there was little the State Bar could do to him.

“I forgive them for what they did, but I still believe in consequences for your actions, even 23 years later,” he wrote.

Womack wrote in a December 2015 response that he didn’t remember the case. He said he probably was only involved in offering the plea to Mansfield.

“Whether the child recanted later, I do not know,” he wrote. “But it is clear when this case was resolved by the agreed upon guilty plea, I had no reason to believe that the child had recanted.”

According to the State Bar, Womack in November 2016 agreed to permanent disability suspension of his license and can never practice again. It is unclear what led to his suspension because State Bar records don’t specifically state the reason. Attempts to reach Womack were unsuccessful.

Jergins also gave the bar a written response in December 2015, saying that he had “nothing whatsoever to do with the case.” Jergins said Mansfield was sentenced on his first day working for the district attorney’s office.

Jergins resigned from his bench nine months later but was not disciplined by the bar. His attorney declined to comment.

In January 2018, Mansfield sued Williamson County in federal court, arguing that the county violated his constitutional rights. County lawyers contend that because prosecutors are state officials and not county employees, the county is not responsible for what happened. They also claim that because Mansfield’s case involved a plea and not a trial, prosecutors were not obligated to disclose all evidence. The case is set for trial in February.

The current district attorney, Shawn Dick, says he is working to restore confidence in the county’s justice system. The county, he says, has not done a thorough review of all cases Anderson’s office handled, to his knowledge. But he says doing so would require more staff and would be difficult because the cases are so old that many of the files have been destroyed, and witnesses, victims and defense attorneys might be dead.

“The time and resources it would take to do that, we basically would have to stop handling new cases,” he says.

John Raley, a Houston attorney who represented Morton, says he fears there are more cases in which prosecutors bent on landing a conviction betrayed their duty to fairness and the Constitution. Mansfield’s case, he says, underscores the need for a systematic review of convictions under Anderson’s leadership.

“A prosecutor who concealed evidence of an eyewitness to murder would not do something like that in a vacuum,” he says. “I am confident there are other cases.”

Mansfield believes the system that convicted him was badly broken, but he is relieved to finally be free of the shame it inflicted on him.

On the day the judge reversed his conviction, Mansfield was so overcome with emotion he could barely speak when he called his stepfather. As a teen, Mansfield, who had little relationship with his father, had proudly taken his stepfather’s last name.

“Our name is getting cleared, Daddy,” he repeated tearfully, over and over. “Our name is getting cleared.”