When Kids Kill

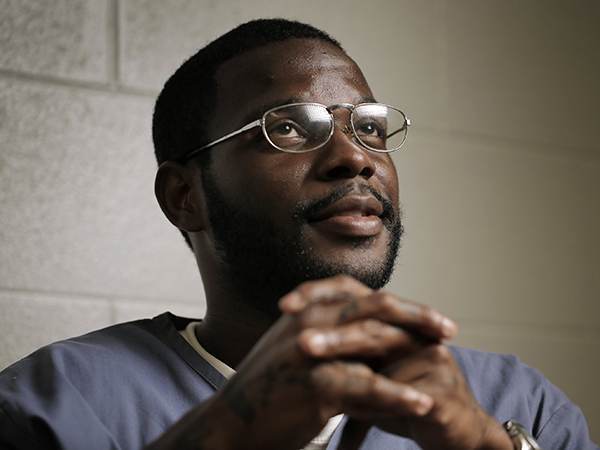

Aaron James Wright is serving 35 years in Holmes Correctional Institution in Bonifay, Fla. [Bob Self/The Florida Times-Union]

For many young homicide offenders, trouble easy to find

In the absence of anything better to do, trouble is always available. ■ For the dozens of Duval County kids who have taken part in a crime that ended a life, many said they weren’t looking to hurt someone; they were looking for something to do, and to maybe make a little money, too. ■ They were bored, skipped school and ran with their like-minded friends. Sometimes, the thing to do became stealing, selling drugs or swapping guns.

Aaron Wright was one of those kids.

Wright, who spent much of his childhood in West Palm Beach, said he was a “geek” and a busy student athlete down south. For a time, he’d bounce back and forth between his dad’s house in South Florida and his mom’s place in Jacksonville, finally settling in the Arlington area when he was 16.

In Jacksonville, he found friends who introduced him to parties and the kind of fun he’d never been allowed to take part in before.

It was with those friends that Wright started committing robberies. Somewhere between 30 and 40 over about a six-month span, he thinks.

Wright didn’t find it scary; it was adventure. He didn’t worry about getting caught, he said, because he believed only stupid people went to prison. And, he thought, he wasn't stupid.

“Everything was a thrill,” he said.

Two of those same friends were with Wright on the July 2005 night that led to all three sitting in prison today for murder.

Wright, along with Michael Workman, 15, and Keith Monford, 16, were looking for someone to rob late on a June 2005 night.

They found 55-year-old Mary Jane White, who they put in the backseat with Wright. Wright duct-taped her mouth but said they wouldn't kill her. Then Workman did kill her.

Wright said he didn't know his friend had a real gun that night. At one point he thought about leaving his friends behind at the scene. "If I had pulled off and left him ... he would have killed me. That's just something you don't do."

All three men were later arrested. Wright is serving 35 years for his role in White's death. Workman, the shooter, got 40 years. Monford, the third teen, got 20 years.

Wright, like most of the young homicide offenders who have corresponded with the Times-Union over the last year, got into trouble with friends.

For these kids, without something constructive to do in their communities, crime became their fun.

For many of these young offenders, school was a struggle, especially going in to the middle school years. Being held back or put in special education was common, while others describe needing help with class but not getting it. The frustrations they felt in the classroom were compounded by the isolation that followed among their peers.

In hindsight, Wright and others in his position, wished for more structure, whether from the adults in their homes who could have helped them with homework, or from a school or community center that could have provided activities.

Renata Hannans, a Jacksonville-based youth advocate and volunteer with incarcerated youth, said consistency is key to getting through to at-risk kids.

“You can’t just meet someone one time and tell them there’s a better way without showing them a better way,” she said. “That’s the problem: We just talk at them instead of talking to them.”

A lot of these kids are just seeking love, she said, so where are they going to fill that void? With constructive things to do? Or with like-minded and just as bored friends?

“Exposure is key. Exposure to education. Exposure to traveling. Exposure to career options,” Hannans said. “If all you see is rappers and drug dealers, then you think that’s all you can be. … But nobody told you you can be a dentist or a writer.”

Tamarius Bowes, now 24, said his greatest strength as a child was his mind. He just didn’t know what to do with it then.

“We fall in with the wrong crowd because we're bonded by our struggles, by our environment ... so we all feel the same,” Bowes said. He was 17 in 2011 when he shot into a crowd at a city park, killing 23-year-old Charles J. Jenkins and wounding a 9-year-old boy in the leg.

“All that spell nothing but trouble, and like my grandma always told me, ‘Trouble is easy as hell to get into and hard as hell to get out.’ ... How about we try to make it hard to get into trouble?”

‘A DIFFERENT CALIBER OF FRIENDS’

Of the 25 people who took the Times-Union’s survey, 21 said they were with other people at the time of their crimes. Some had just one co-defendant, but others had two, three or four on their cases.

That holds especially true for the very young teens and pre-teens arrested on these types of charges. The Times-Union looked at the cases of 20 young killers who are currently locked up for crimes committed before they were 16.

Eighteen of the 20 had a peer or adult present at the time of the slaying.

Damien Davis was 13 when he shot and killed Jose Lau, according to police. Davis and his four friends — ages 14 through 17 — ordered food and planned to rob the driver.

Corey Odol and Todd Thornton were both 15 when they caught murder charges alongside a 13-year-old boy and an older man who’d ultimately be convicted of three slayings in his lifetime.

Thirteen-year-old Jeremiah Hill was with his 18-year-old cousin when 25-year-old Tony Vernon Johnson was killed at a North Main Street gas station in a gun exchange gone wrong.

“I wish I chose a different caliber of friends out there,” Davis told the Times-Union when asked what he wished had been different about his childhood. “Them young ones thuggin’ real hard out there.”

Carly Dierkhising, an assistant professor in the School of Criminal Justice and Criminalistics at California State University, Los Angeles, said one of the landmarks of adolescence is being more susceptible to what friends may think. In moments of intense decision-making with friends around, that’s when impulsive decisions get made, she said.

That doesn’t mean teenagers are incapable of reason; it’s just harder for them when the pressure is on.

Dierkhising gave two examples: In many states, teen girls can get an abortion without parental permission because they have time to talk things over with a doctor and make the decision that is best for them when given time to think it through.

But, when it comes to teens and learning to drive, states place restrictions on who can be in the car, what age they have to be and when teens can be on the road. That’s because they recognize that teens are easily distracted and driving can require reacting quickly under pressure.

“We understand youth reaction in that context,” she said.

SCHOOL SETBACKS COMMON

Most of the 25 survey respondents — 56 percent — said they actually liked school. And even more — 68 percent — said they felt safe in their school.

But school was a struggle for many of the young people who wrote to the Times-Union. At least 12 remembered being held back a year or more in school and six said they were placed in special education classes. While their friends and classmates moved on, they fell behind — and grew isolated.

Elijah Crady was in elementary school when he was put in special education classes, which he called "dumping grounds for troubled children with behavioral problems."

In those classes, he said, he felt like a pariah and a misfit.

"The special ed schools are an abomination," Crady wrote. "They do not educate, but alienate."

Crady was 16 when he took part in the robbery and murder of 53-year-old David Drury in 1998, alongside three older co-defendants.

Several of those surveyed remember doing well and loving school early in their elementary years, but struggled as they got older, either with behavior, attendance or the lessons.

Sara Baldwin, director of the mitigation unit at the Public Defender’s Office, said it’s not uncommon for parents to refuse to have their children screened for learning disabilities, or to not participate in getting an IEP made — an individualized education program for special education students. For students with learning disabilities, they can be hard to overcome without proper support.

Held back in class, not able to afford sports or other activities or not allowed to partake because of bad grades or behavior, kids look for a place to fit in and a caring adult to listen to them. But it wasn't always easy to find. Just five of the 25 who took the survey said they’d had some kind of mentor or positive role model. But for those who did, a teacher or coach from school was the most common answer.

For Bowes, it was Ms. Reyes, the history teacher.

“She wasn’t really a mentor,” Bowes wrote of Reyes. “She just cared a lot.”

‘THERE’S NO PLAYGROUNDS’

When it has come to serving children, city dollars for summer camp and afterschool programming have gone to programs working in the neighborhoods with the greatest need. But, of the nearly $14 million of city dollars spent on those programs, most have gone to programming for elementary school and some middle school-aged kids.

In early 2017, the board of the Jacksonville Children’s Commission — the now-defunct predecessor of the city’s Kids Hope Alliance — voted to cap the number of afterschool program seats for high school students to 233. A task force had studied out-of-school time, and recommended focusing resources on programming for younger children.

Paul Martinez, CEO of the Boys & Girls Club of Northeast Florida, stood to oppose that cap. He asked, if a program like theirs was working, why limit it?

“The elementary kids aren’t shooting each other, Jon,” Martinez said to then-commission CEO Jon Heymann. “They aren’t.”

While the Kids Hope Alliance is now wrapping up its first year and still distinguishing itself from the commission, its CEO, Joe Peppers, has said the KHA has not and will not honor that limit on high school students, calling it “foolish” when he spoke to the Times-Union editorial board in August.

Peppers said when he first began as CEO of the alliance, he was heavily focused on early learning. But, he realized, “we won’t win fast enough that way.”

“It would be negligent for us to not really think of creative ways to ramp up our teen programming,” Peppers said, adding that more robust programs need to be in place for summer 2019.

When it has come to serving children, city dollars for summer camp and afterschool programming have gone to programs working in the neighborhoods with the greatest need. But, of the nearly $14 million of city dollars spent on those programs, most have gone to programming for elementary school and some middle school-aged kids.

In early 2017, the board of the Jacksonville Children’s Commission — the now-defunct predecessor of the city’s Kids Hope Alliance — voted to cap the number of afterschool program seats for high school students to 233. A task force had studied out-of-school time, and recommended focusing resources on programming for younger children.

Paul Martinez, CEO of the Boys & Girls Club of Northeast Florida, stood to oppose that cap. He asked, if a program like theirs was working, why limit it?

“The elementary kids aren’t shooting each other, Jon,” Martinez said to then-commission CEO Jon Heymann. “They aren’t.”

While the Kids Hope Alliance is now wrapping up its first year and still distinguishing itself from the commission, its CEO, Joe Peppers, has said the KHA has not and will not honor that limit on high school students, calling it “foolish” when he spoke to the Times-Union editorial board in August.

Peppers said when he first began as CEO of the alliance, he was heavily focused on early learning. But, he realized, “we won’t win fast enough that way.”

“It would be negligent for us to not really think of creative ways to ramp up our teen programming,” Peppers said, adding that more robust programs need to be in place for summer 2019.

Among the 25 people who took the Times-Union’s survey, 21 said that at some point they had a job or played on a sports team. Some, like Wright, a carhop at Sonic, even had jobs at the times of their crimes. When jobs were available, they were low-paying and in fast food. Wright said his checks from Sonic were so small, he usually didn't bother to cash them and instead spent the tips he earned. His main incentive for the job was being around the girls at work.

But they agreed: having something fun and positive to do would have helped keep them out of trouble.

“Ride through any hood at night (don’t) and see how many kids are out there,” Wright wrote to the Times-Union. “I believe — scratch that — I know that if I had more positive than negative activities to be involved in then I never would have been involved in some of the foolishness that I was involved in.”

Hannans, the youth advocate, gestured toward her car window as she drove through the Moncrief area of Northwest Jacksonville, located in the city's ZIP code with the most murders year after year.

“They’re easily influenced, they’re negatively impacted by their environment,” she said. “What is there to do around here? … There’s nothing to do. There’s no rec center. Empty, abandoned buildings. There’s no playgrounds.”

When kids have nothing positive to do with their time, she said, they hang out with their friends and then find trouble. Hannans gave credit to many of the city’s nonprofits that work with kids, but asked, where are the safe places to just go, hang out and be a kid? Somewhere to play sports, make music and create art?

“You can have the building all day. It’s not the building. It’s not the rec center that makes it work,” Hannans said. “It’s the people that you get there to work with the kids, to have relationships with them that will make them want to come. Period.”

Ride through any hood at night (don’t) and see how many kids are out there. I believe — scratch that — I know that if I had more positive than negative activities to be involved in then I never would have been involved in some of the foolishness that I was involved in.”

Aaron Wright

GO WITH THE FLOW KID

Elizabeth Gray, Wright’s mother, described herself as a strict mom, one who never had to lay hands on her kids to get obedience and whose phone calls were always answered by her kids. Wright included.

She worked a full-time job as a correctional officer at a prison in Georgia and part-time as a nursing assistant to provide for her five kids as a single mother. Her son never needed money, she said.

When her children's friends came over to play or hang out, they did so at her house. She wasn’t worried about Wright's friends. She saw them nearly every day and knew about their families.

It’s been more than 13 years since Wright and his co-defendants’ crime. But Gray still thinks about what could have helped her son. Should she have done something differently? What if they had stayed in West Palm Beach? She wondered, “Where was I?”

“I beat myself up with that, too,” she said. “If I hadn’t have moved … He just … I don’t know.”

Gray said she understands people do things to fit in, but robberies?

“Why would you even want to take part in it?” she asked. “Even though it’s been so long, I still don’t know that.”

Wright, now 30, said he doesn’t really understand his former self, or why he took part in the things he did. He didn’t need the money because his mom and the tips from his job as a carhop at Sonic Drive-In took care of that.

The best he can figure is that he was just a go with the flow kind of kid. It didn’t matter what the flow entailed.

“If they wanted to go rob somebody, I wasn’t going to be the one to go play video games or something,” he said. “ 'OK, this is what we’re doing.' OK.”