Troubled waters in Newport

The nor’easter that hit Rhode Island on a spring night in 2007 delivered only a glancing blow to most parts of the state.

But in the City By the Sea, it nearly landed a heavy hit.

The wind and driving rain during the April 16 storm pounded the dam system that holds back South and North Easton ponds, which help supply drinking water to most of Aquidneck Island. Wind-whipped waves churned up in the runoff washed out stretches of the earthen embankments along the western and northern edges of the south pond, eating away as much as two-thirds of the barrier in some places.

City workers and crews called in from Naval Station Newport hauled sandbags up to the dam and piled them around the eroded portions in a last-ditch effort to prevent the pond from breaching.

“Were it not for the long hours and hard labor of these dedicated employees, the dam may have been washed away during the storm, with catastrophic results of the loss of our drinking water and flooding of the surrounding neighborhood,” the City Council declared in a resolution a few weeks later.

It wasn’t the first time the dams around the Easton ponds sustained storm damage. The surge from the Hurricane of 1938, which reached 11.6 feet above mean sea level in Newport, destroyed much of the southern embankment. Hurricane Gloria in 1985 caused a partial breach of the northern embankment that separates the two ponds.

In 2012, the waves and surge from Superstorm Sandy reached within a foot of the top of the 12-foot-high southern dam, leaving a record of its height in the debris left behind, which included a big, green dumpster carried up from Easton’s Beach, situated hundreds of feet away on the other side of Memorial Boulevard.

For Dave McLaughlin, executive director of Clean Ocean Access, a Middletown-based environmental group, the signs are clear. Climate change is making the ponds, which are part of a system that some 40,000 people rely on for drinking water, more vulnerable.

Sea levels in Newport have risen 9.6 inches since 1930 as ocean currents slow, polar ice caps melt, and waters warm and expand. The protective beach in front of the ponds is eroding, largely due to severe coastal storms, which appear to be occurring more often. It retreated more than 70 feet in places between 1939 and 2003, according to a University of Rhode Island study.

The changes mean that storm surges reach higher and further than in the past. Extreme rainfall events, which in the Northeast have shot up in frequency in recent decades, pile on the pressure from the inland side.

“It’s not a matter of if, but a matter of when, the dams will be compromised,” McLaughlin says.

Rhode Island’s water-supply network is fragmented. While a single utility dominates the electric and heating sectors, the distribution of drinking water has been carved up into fiefdoms.

The Scituate Reservoir provides water to 60 percent of the state, including Providence, Warwick and Bristol County, while Pawtucket, Central Falls and Aquidneck Island also largely rely on reservoirs, but the southern half of the state almost entirely uses groundwater, whether it’s supplied through municipal systems or household wells.

There are 34 large water utilities, as well as more than 400 small water suppliers — housing estates, trailer parks, etc. — scattered throughout Rhode Island.

But this multiplicity of water suppliers is facing a common threat.

“At a state level, if we’re looking at all the impacts of climate change, drinking water absolutely rises to the top,” says Shaun O’Rourke, chief resiliency officer for Rhode Island. “Why? It isn’t just one neighborhood or one municipality where it’s being felt more than others. This is truly a statewide issue.”

“It’s a public health issue,” says Laura Bozzi, climate change program manager for the state Department of Health. “We need this water to live.”

Changing rainfall patterns are one factor that affects water supply. Rhode Island is getting a greater amount of annual rainfall on average than in the past, but it’s becoming segregated into smaller windows in the spring and fall.

Runoff from intense rainstorms is washing bacteria and other pathogens into ponds and streams. Nutrients, too, are being picked up in the stormwater, fueling the growth of algae that can sometimes be toxic. Heat also helps these microorganisms proliferate.

Higher temperatures mean more water is lost to evaporation rather than being allowed to soak into the ground. Summer droughts can run down supplies when they’re needed most.

All of those impacts are occurring to varying extents across the state. But there are additional threats to coastal communities. Water systems with low-lying treatment plants, pump stations and distribution pipes are threatened by higher storm surges and seas that in the Northeast are rising at a faster rate than the global average. Wells near the shore are at risk of saltwater intrusion as ocean waters push inland and mix with underground aquifers.

“SafeWater RI,” a 2013 report commissioned by the health department, assessed risks from flooding, hurricanes, drought and sea-level rise for the major water utilities in Rhode Island. It projected $87.5 million in damage from sea-level rise by 2084, based on scenarios by federal scientists that have since been upgraded for severity, as well as a total of $52.7 million in damage from a single hurricane and surge.

Of the 10 utilities with the greatest risk, eight are coastal, including the Warwick Water Division, the Westerly Water Department and the South Kingstown Water District.

The Newport Water Division ranked near the top, receiving the highest possible scores — signifying the most vulnerability — for sea-level rise, coastal flooding and hurricane damage.

Even if seas stopped rising today, the Easton ponds, which straddle the Newport-Middletown town line and are fed by Bailey Brook, would still be vulnerable to a surge from the baseline storm used by the Federal Emergency Management Agency in determining flood risk.

According to the FEMA maps, the surge and waves from a 100-year storm, one with a 1-percent chance of happening any year, is projected to be 16 feet at South Easton Pond, which would easily overtop the southern dam. The pond and its dams are located in what’s considered the highest-hazard zone in the flood maps, where breaking waves of at least 3 feet in height are projected on top of a surge.

One of Newport Water’s treatment plants, Station No. 1, is located on the southwest corner of North Easton Pond, just outside the wave zone, but it is still expected to flood in a 100-year storm. According to STORM TOOLS maps developed by the Rhode Island Coastal Resources Management Council and URI, floodwaters at the plant would rise 3 to 4 feet high. And with an additional 2 feet of sea-level rise, which in some scenarios could occur in the next two decades, the waters in the same storm would reach nearly 5 to 7 feet high.

Sea-level rise alone could eventually flood the plant. With 7 feet, the water would be at its door. With 10 feet — close to the most extreme projection for the region by the end of the century — they would envelop the building.

The Hazard Mitigation Strategy for Newport, written in 2008, recommended a study of the ponds’ vulnerability within three to five years.

“Of particular concern is the Easton’s Pond shore bank facing Easton’s Beach. It has been reinforced to withstand storm surge; however, it is unclear if it can withstand the highest storm surge this area can potentially receive,” the strategy said.

A 2016 update approved by FEMA again recommended a study, listing it as a high-priority item for the city. That same year, when Newport Water was seeking permission from the state coastal council for repairs to one of the pond’s embankments, Save The Bay, the Providence-based environmental group, also urged a study, arguing that the project that was then before the council “is only a temporary and partial fix to the larger problem of the vulnerability of this water supply to climate change.”

Pointing to the 2013 health department report on drinking water, the group wrote that “the City must identify, prioritize and implement short and long term adaptation strategies … to plan for the future viability of the water supply.”

Several years ago, the coastal council and URI unsuccessfully sought federal funding to do their own study of the risks to the Newport water system. The coastal council is now finalizing an agreement with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to carry out a comprehensive study of the state’s coastal infrastructure. Near the top of their list is the Newport water supply, says council executive director Grover Fugate.

“It’s one of the areas that we’re concerned about that’s susceptible to both storm surge and sea-level rise,” he says.

It’s true that the Newport Water Division has not assessed in a single study the potential climate-change impacts to all nine of its reservoirs on Aquidneck Island and the Sakonnet Peninsula, two treatment plants and 200 miles of pipes.

But they’re not ignoring the threats, say Julia Forgue, director of utilities for Newport, and Robert Schultz Jr., deputy director of engineering. When Newport Water rebuilt Station No. 1 five years ago, it raised mechanicals and other systems as much as possible, they say.

Staff have taken into account sea-level rise and storm surge in infrastructure reports the division makes to the state Water Resources Board every five years. And they are considering their impact in separate studies of individual dams and reservoirs. The first, on the Easton ponds, is nearing completion, and the division plans to eventually move on to its other coastal reservoirs: Gardiner and Nelson ponds, both located behind Second Beach in Middletown, and Nonquit Pond, near the east bank of the Sakonnet River in Tiverton — which, like the Easton ponds, are all in the 100-year floodplain.

One of the difficulties they say they face is in sorting through the different maps and projections for surge, sea-level rise and flooding that in some instances conflict with each other. For example, the state coastal council and its partners at URI argue that federal flood maps significantly underestimate wave heights in storm surges and overestimate the protection offered by sand dunes, so they project more severe flooding than FEMA.

In addition, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has put forward a variety of sea-level rise scenarios based on a host of uncertainties. For example, by 2070, seas in Newport could rise a foot or less or more than 6 feet, according to the projections. The Rhode Island coastal council has adopted NOAA's "high" scenario as its guide, which estimates about 5 feet of rise in the next 50 years.

It’s not just that the models sometimes diverge. Planning for impacts on water supplies has to account for how demand might change, too. Increases in sea levels that are high enough to threaten the coastal ponds would also inundate downtown Newport and large tracts of the water division’s service area.

“You’d have significant areas that were no longer developable, and that would change the demands on the system,” Schultz says. “That’s not something that you can really forecast.”

South Easton Pond, which is used on a daily basis, is vulnerable to a surge, Forgue says, but it represents only about 10 percent of Newport Water’s usable storage capacity. In total, the system’s coastal reservoirs — South and North Easton ponds, Nelson Pond, Gardiner Pond and Nonquit Pond — hold about 38 percent of the system’s total capacity.

If a surge were to contaminate any of the coastal ponds with saltwater, there are upland reservoirs that could meet demand in the time -- ranging from a day to as long as a month -- it would take for new freshwater to come in and dilute the salt levels below the Environmental Protection Agency standard of 250 parts per million, according to Forgue. The same is true for water treatment. If something happened to Station No. 1, there is a second plant, the Lawton Valley facility in Portsmouth, which sits at a higher elevation, that could carry the load.

Although Clean Ocean Access, Save The Bay and other groups point to Sandy as a warning sign for the island’s water supply, the storm had little real impact in the end. South Easton Pond was taken offline as a precaution, but it was soon returned to service. There was no damage to the dams. More worrisome was the 2007 nor’easter.

“It was drastic. On the west embankment, it was down to inches,” says Forgue. “I’ve never seen anything like it.”

Newport Water repaired the damage afterward and armored portions of the dams with stone riprap. It carried out more work on the embankment in 2016 after getting clearance from the state coastal council. Once the current study of the dams at the Easton ponds is complete, the division plans to move forward on additional projects to strengthen them, including potentially armoring the southern portion.

But, Forgue points out, Newport Water already has the highest rates of any drinking water system in Rhode Island, and any further work requires permission from state regulators to raise them again.

State Rep. Lauren Carson, a Newport Democrat who chaired a House commission on climate change in 2015 and 2016, says that funding is an issue for any projects aimed at protecting infrastructure from sea-level rise.

“I don’t know where the state’s going to get the money,” she says. “The longer we wait, the more it’s going to cost.”

The Green Economy Bond approved by state voters last November, for the first time in Rhode Island set aside funding for climate-resilience projects, including those for drinking water systems; but the $5 million is a relatively small amount of money, according to O'Rourke, the state's chief resiliency officer.

He hopes to increase the size of the program in the future and is working on other initiatives, including a partnership with The Nature Conservancy modeled on something similar in Massachusetts, which aims to identify resilience projects in communities and start funding them.

Meanwhile, the health department is strengthening regulations to help protect water systems. All new treatment plants must now be built above the 500-year flood elevation, the extent to which waters would reach in a storm that has a 0.2 percent chance of happening in any year. If an existing plant is “substantially renovated,” it must be elevated and flood-proofed.

The agency also now requires all water systems to test periodically for algae blooms. And it is working on a regulation with the state Water Resources Board and O’Rourke’s office to ensure that all systems are tied into backup water suppliers.

“Many of the water providers around the state operate as an island and they’re not all well-connected, so if one goes down there’s limited ability to draw water from another area,” O’Rourke says. “We think of this as pre-planning and not waiting until the disaster hits.”

Westerly and Charlestown are examples of systems in need of alternate connections, says June Swallow, chief of the health department’s office of drinking water supply.

“It would be great if we could wheel water all around the state from Westerly through South County and up the coast to connect to our major supplies in Pawtucket and Scituate,” she says, though she acknowledges the costs. “That would be a significant improvement in resiliency.”

Some drinking water suppliers are already starting to prepare for climate change. The Providence Water Supply Board is working to protect the Scituate Reservoir by planting trees more adapted to hotter weather that would buffer the watershed and filter out contaminants.

Woonsocket is building a new $56-million water treatment plant at a location above the 500-year floodplain and installing backup generators throughout its drinking water system.

The Four Seasons Mobile Home Cooperative Association in Tiverton is putting in a new generator and burying distribution pipes deeper underground to protect them from extreme cold.

Then there is the Bristol County Water Authority, which is taking a more aggressive approach.

In February, the authority, which supplies water to the residents of Bristol, Warren and Barrington, decommissioned a circa-1908 water treatment plant in Warren that the 2013 health department assessment ranked among the most vulnerable to storm damage in Rhode Island.

The authority is working with Save The Bay, the state Department of Transportation and O’Rourke on a plan that could eventually lead to the removal of two dams on the Kickemuit River that hold back reservoirs it no longer needs.

Bristol County has gotten its water from the Scituate Reservoir since 1998, when it completed a pipeline under the Providence River and became a wholesale customer of Providence Water. The Kickemuit reservoirs were maintained as a backup supply, but they will become redundant with a plan to hook into the Pawtucket Water Supply Board’s system.

Rising maintenance costs and the threat of storm damage pushed the authority to close down the treatment plant, which is located in an area that could see some of the biggest impacts from rising seas in the state. The reservoirs, too, are no longer good sources of water. Moon tides already send water upriver high enough to go over the spillway into the lower reservoir.

Now, faced with a bill of up to $290,000 to bring just the upper dam into compliance with state regulations, the authority is working on a plan to remove part of it. It would cost about twice as much in the short term but would save money in the long run, says Pam Marchand, executive director of the authority.

“There’s no need to maintain infrastructure that’s becoming obsolete,” she says.

One afternoon, she, Ken Booth, the authority’s operations manager, and Wenley Ferguson, director of habitat restoration for Save The Bay, climb steps cut into the upper embankment, which was built after the surge from Hurricane Carol in 1954 contaminated the lower reservoir with saltwater.

The reservoir spreads out below them, its waters reaching into an oak swamp. Ducks and swans paddle among the reeds along one bank. Ferguson points out a couple of hooded mergansers, their distinctive black-and-white fan-shaped heads setting them apart from the other waterfowl.

The top of the dam is clear of vegetation, but it’s apparent why it would cost so much to meet code. Each of its sloping sides is covered down to the waterline in a tangle of bushes and trees. The plants would need to be removed, root balls and all, and the holes refilled to comply with dam-safety rules.

The plan instead is to remove a 30-foot-wide wedge that would allow the river to flow naturally once again.

The water level where the reservoir is now located will surely drop, and the river will probably find a meandering path downstream. The portions of the newly uncovered bottom would be muck to begin with, but Ferguson is confident that seed pods hidden in the mud would allow plants to grow within a year or two.

“There aren’t many silver linings to sea-level rise, but this may be one of them, where you’re talking about restoring a habitat,” she says.

It’s an example that may apply to Newport.

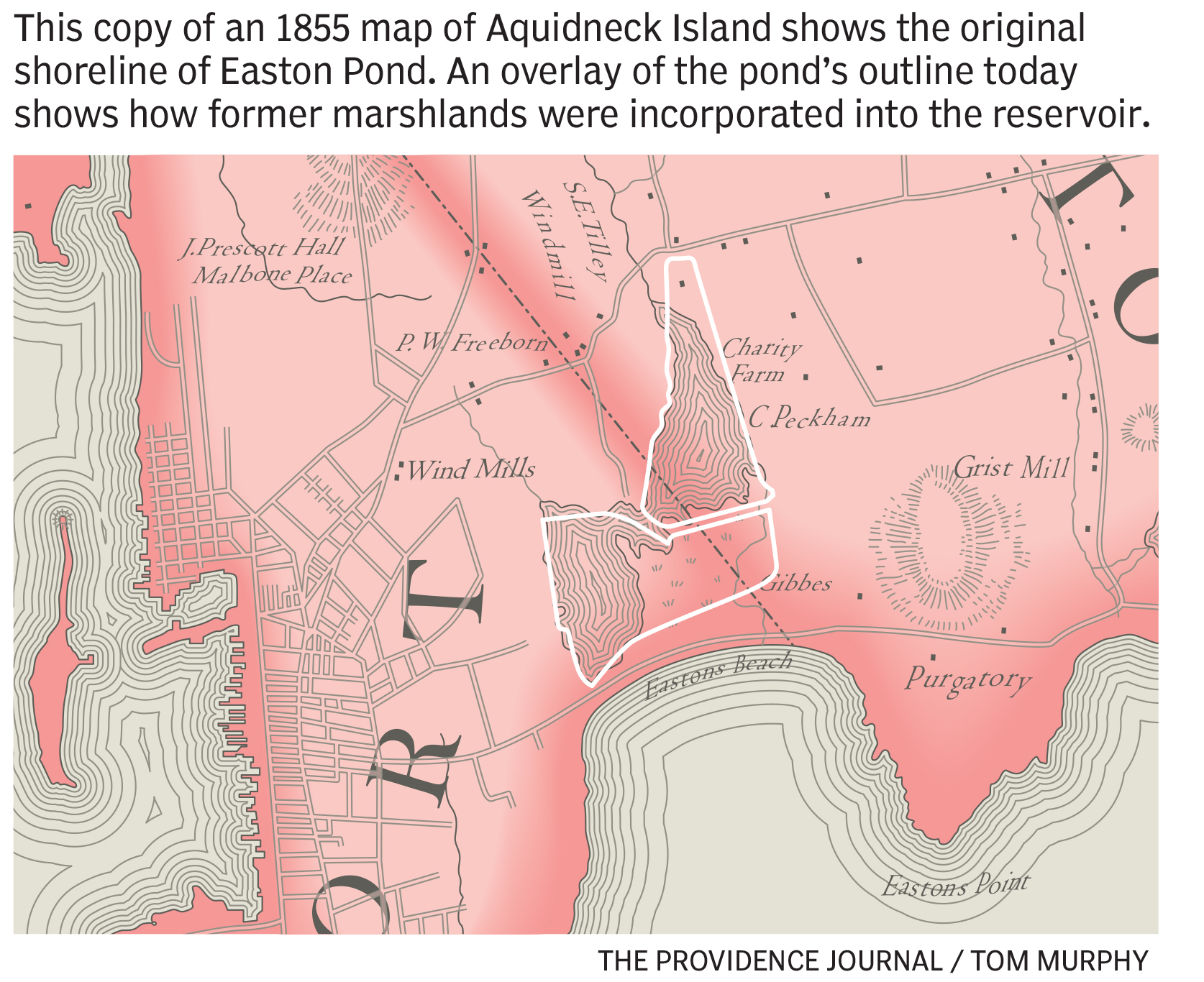

In his office overlooking the Easton ponds one morning, McLaughlin pulls out a scan of an 1855 map that shows the ponds before they were dammed in the late 1800s. It depicts a single water system with two main bodies of water, one to the northeast and the other, at the end of a short, crooked channel, to the southwest. Bailey Brook flows into the northeastern portion and continues on through a salt marsh before emptying into the Atlantic Ocean.

He argues that taking down the southern embankment and restoring the original marsh will create a buffer that will enhance the protection of North Easton Pond and the Station No. 1 treatment plant. Save The Bay also supports taking out the dam.

“We have to start looking at ways to move these assets back in the watershed,” McLaughlin says.

Of course, the Bristol County Water Authority can consider removing the dams on the Kickemuit, because its reservoirs on the river are no longer needed. The same is not true of South Easton Pond, which is still an integral part of the Aquidneck Island water system, says Forgue, who declined comment on removing the southern dam.

McLaughlin appreciate s Newport Water’s dilemma, but says that discussions about the long-term future of the island’s water supply should start happening now. Sea-level rise is inevitable, and retreating from the coast is one possibility that has to be considered.

“It doesn’t matter what map you look at, you can see the trend,” he says.

— akuffner@providencejournal.com

(401) 277-7457

On Twitter: @KuffnerAlex

Newport's water system is notoriously complex

Julia Forgue, director of utilities for Newport, describes the water system she oversees as the most complex in Rhode Island and perhaps in all of New England.

That’s because it’s the only water utility in the six-state region that carries out advanced treatment using carbon filtration, a necessity because, unlike other places with supplies far from developed areas, such as the Scituate Reservoir, the watersheds on Aquidneck Island are covered in houses, farms and businesses, and Newport Water’s supplies are prone to runoff-fueled algae blooms and other contamination.

“We’re on an island,” Forgue says. “We don’t have an alternative source.”

The complexity is heightened by the number of reservoirs — a total of nine, with three in Portsmouth and one each in Newport, Middletown, Tiverton and Little Compton — a pair of treatment plants — the revamped Station No. 1 next to the Easton ponds in Newport and the newer Lawton Valley facility in Portsmouth — and nearly 200 miles of pipes.

The precursor to the modern-day system was founded in 1876 by George H. Norman, one of the first owners of the Newport Daily News and a contractor who had worked on the Boston water network and would go on to build water utilities throughout the Northeast. Until he stepped forward with his plan, Newport had relied on a network of wooden pipes that delivered water from a spring located at a site most recently occupied by a Citgo gas station in the heart of the city.

The key to Norman’s proposal was making use of Easton Pond, which was then connected to the Atlantic Ocean through a tidal inlet.

“... the vast body of overflowing water swept a deep channel, which the sea, rolling far up towards the pond, widened and made permanent. Boats came from ships in the offing, and followed its course to ‘Green End,’ with no fear of grounding,” wrote Annie Rebecca Coggeshall in the Atlantic Monthly in 1858.

In 1877, Norman’s company, the Newport Water Works, built an earthen dam that bisected the pond from north to south. The northern portion, North Easton Pond, became the first drinking water reservoir for the city.

In 1896, the company built a second embankment to encompass the southern portion of the pond as well as a salt marsh along its eastern end, creating South Easton Pond. In the decades that followed, the water works expanded its network of reservoirs, carving Gardiner Pond out of a salt marsh behind Second Beach in Middletown and acquiring others, including Nonquit Pond, near the east bank of the Sakonnet River in Tiverton.

Water quality was always a problem for the system. In 1897, the Army surgeon at Fort Adams complained that the water from the Easton ponds was contaminated by waste from humans and animals, writing, “The water was bad at the beginning, has remained so, and there seems to be no prospect of a better supply in the immediate future.”

Newport took over the water system through eminent domain in 1939 after the state Supreme Court upheld a ruling that the city’s ownership was a public necessity to improve water treatment and reduce rates.

Today, the Newport Water Division supplies water to all of Newport, most of Middletown and a small portion of Portsmouth on a retail basis. It also provides water on a wholesale basis to the Portsmouth Water & Fire District and Naval Station Newport.

There has been talk of tying into Fall River’s water supply as a backup, but Forgue says doing so would be complicated by cross-state issues and expensive because of the distance to the Massachusetts city.

The division spent $85 million on upgrades to its treatment plants, completed in 2014, but water quality is an ongoing problem.

“Newport is very challenged with their quantity of supply and their sources of supply. They do struggle to assure they have enough high-quality drinking water for the area,” says June Swallow, chief of the health department’s office of drinking water quality.