LIVING IN LINDEN

Exploring a neighborhood's struggles and possibilities

Math problem: Most Linden kids aren't going to Linden schools

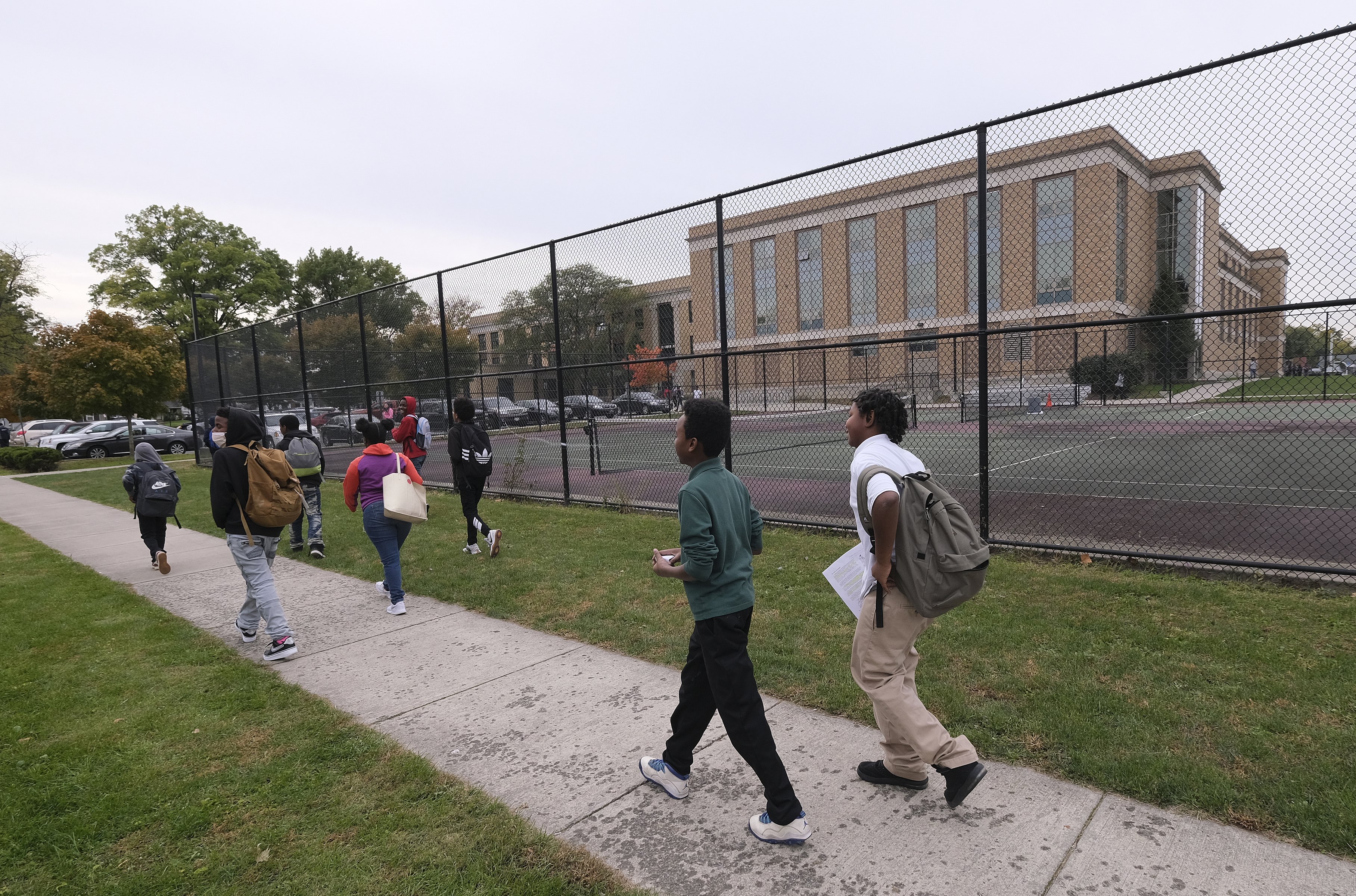

Columbus City Schools and the state made a $38 million investment in Linden-McKinley High School a decade ago, doubling the size of the historic structure and renovating it into what some residents predicted would be a redevelopment engine for the neighborhood.

"Once that school is there, it's going to uplift the entire community," George Walker Jr., chairman of the South Linden Area Commission, said at the time.

But today, the sparkling building is the least-popular high school in the district. Despite that Linden-McKinley has 2,157 students assigned to it by address —more than any other district high school — more than three out of every four assigned students go somewhere else.

On Tuesday, the city released its One Linden community plan which, among other things, addresses education and its importance in reviving the Linden area.

One section, "Supporting Student Success," acknowledges that declining enrollment at Linden-area schools has diminished the role of schools as community anchors.

Many members of the working group who helped shape the plan "voiced a desire for Linden's historic public schools to become symbols of community pride" and suggested incentives to lure students back to neighborhood schools. Those include setting up a fund to provide small monetary awards to parents who read to their children.

But Linden schools have a way to go.

More than 1,600 students assigned to Linden-McKinley attend one of 75 other schools, including 36 charters, district records show. Only 629 students attend Linden-McKinley, which could accommodate more than 1,000, and 238 of those are seventh- and eighth-graders moved in to help use the space. About 100 students transfer in from other schools.

Enrollment is so low that a facilities panel recommended last Monday that Linden-McKinley be closed as a high school, its upper classmen transferred to East High, and the building converted into a middle school.

The district's other Linden schools are barely more popular among those assigned to them: none attract more than about a third of the assigned neighborhood residents. Of the more than 9,000 students assigned to nine Linden buildings, more than 6,500 elect to go elsewhere for their education, including a few hundred who go to Linden's two district lottery schools: Oakland Park Alternative Elementary School and Columbus Alternative High School.

Some numbers provided in the One Linden plan:

• Enrollment at Linden-McKinley dropped 6.3 percent between 2005 and 2016 while enrollment at Columbus Alternative grew by 30.3 percent.

• While enrollment at Linden Elementary School dropped by 13.6 percent between 2005 and 2016, enrollment at Hamilton STEM Academy grew by 122 percent, and East Linden and Windsor elementary schools by 50 percent.

• The 3,916 students living in one of Linden's primary ZIP codes, 43211, attend 102 city schools and 29 nonpublic schools with vouchers.

• Linden-McKinley STEM Academy had a four-year graduation rate of just 55 percent in 2016 and a chronic absenteeism rate — defined by the state as 10 percent or more of the school year — of 72 percent. That compared to 32 percent at Columbus Alternative.

"If you give this community an opportunity, it will respond," said Rodney Kent, a Linden native and booster who now lives on the East Side. "They are constantly fighting negativity."

Kent, who is fighting to keep Linden-McKinley open as a high school — he was on the school's 1967 state championship basketball team — blames the district for the schools' lack of popularity. The district's school-attendance zones have divided Linden, he said.

"If you don't have an educational concept that is viable, then there is no need to have your student attend that institution."

After school was dismissed Thursday, Danielle Hook was sitting in her car along Dresden Street waiting for her son, Perniel, a 15-year-old sophomore at Linden-McKinley. Hook, 32, lives just around the corner on Kohr Place. She said it's her son's second year at Linden-McKinley, and she hopes the school district keeps it open.

"Last year was kind of rough," she said, as her son transitioned to his new school. Now he's carrying a "B" average, she said. She doesn't want him to transfer to East, where she went to high school.

Wanda Curtis was picking up her great-grandson, Cashmere Dennis, 12. She said that she attended Linden-McKinley in the 1960s, and that it would be a shame if the district closed it. She said merging East and Linden-McKinley "would be setting up trouble."

"Kids resent the schools merging," she said.

While most South Linden students go to Linden-McKinley, those living farther north attend Whetstone or Mifflin high schools. While about 62 percent of students assigned to Whetstone, in Clintonville, go there, only 35 percent of those assigned to Mifflin attend that school.

North Linden area commissioner John Lathram said that many parents must feel their children have better opportunities outside Linden.

"I think it's difficult to bring them back," he said.

Lathram also is worried about moving kids from Linden-McKinley to East, a rival school.

"Putting the kids in the same school is problematic," he said.

Jennifer Adair, who leads the North Linden Area Commission, has an 8-year-old daughter who goes to school just north of the Linden area: Maize Elementary School. Adair said that she was unaware that so many students who live in Linden go to so many schools outside the neighborhood.

She said it's no secret that crime is a problem in Linden, and that gangs gather outside Linden-McKinley. "Parents obviously want to make the best choice for their kids," she said.

But Adair said that in order to have a strong community, Linden needs strong schools.

Columbus city officials say stabilizing households in Linden is key to fostering better education. That includes bringing down eviction rates in Franklin County that are among the highest in the country, said Carla Williams-Scott, director of the Columbus Department of Neighborhoods.

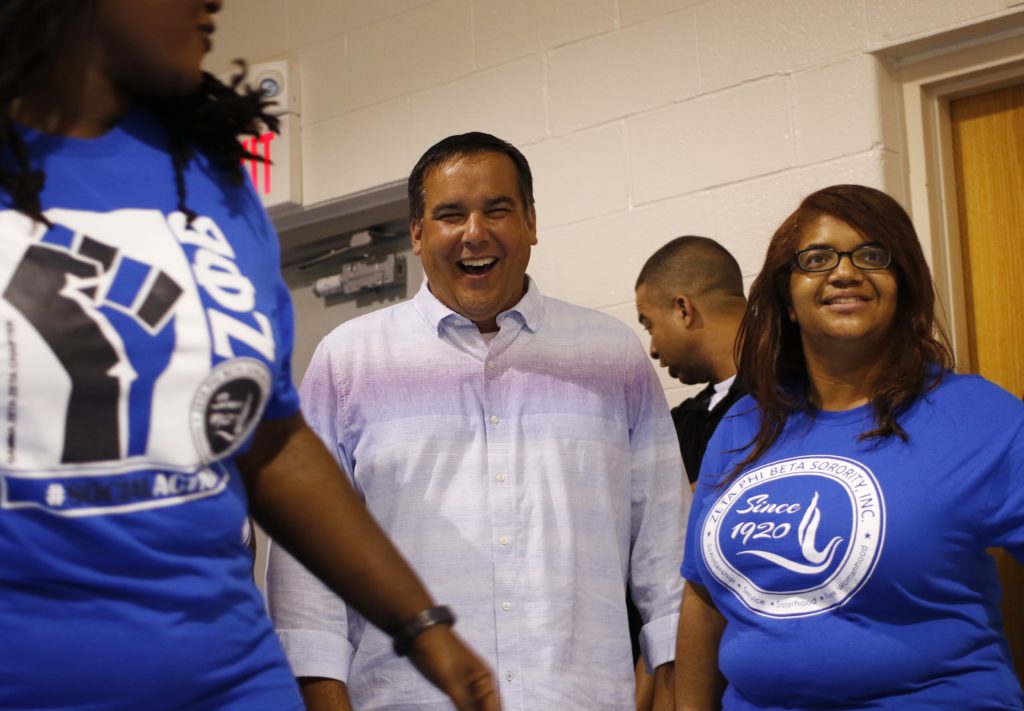

Nick Bankston, the city's manager of neighborhood transformation strategies, said the high percentage of students who go to school outside Linden show that there's more work to be done in the community.

"Education is a critical piece to any neighborhood," Bankston said. "You could probably have the highest performing school in the worst neighborhood and it would turn around (the neighborhood)."

At Hamilton STEM Academy in the heart of Linden, programs are in place to better connect parents to schools and families to resources that will help make life easier for students so they can concentrate on their studies.

Dawn Anderson-Butcher, a professor in the College of Social Work at Ohio State, works at Hamilton with the United Way of Central Ohio and the city in the collaboration. She said the goal is to connect the 470 students with the right programs to help them navigate their lives.

"So many families are struggling getting their basic needs met," Anderson-Butcher said.

"How do we create a school as a hub of community support?

The effort also means getting parents more involved in their children's schoolwork and helping teachers deal with stress.

Since the collaboration began, office discipline referrals at the school have dropped by 14 percent, and the number of students being disciplined has dropped by 15 percent, Anderson-Butcher said.

Bankston said officials are looking at ways other communities have made their neighborhoods safer for students, from volunteers walking children to and from school buses to retirees watching schoolkids from their porches so they feel safe.

Stories that inspire. Coverage that informs. Investigations that affect change. This is real news just when it's needed most. Subscribe today.

Subscribe