It is often in nondescript exam rooms where we are told things that change our lives.

The afternoon of last Jan. 8, I sat in such a room waiting to hear the verdict from a CT scan of a mass on my right kidney.

I was in the Primary Walk-In Medical Center in East Providence. I’d first gone there the morning of Christmas Eve, two weeks earlier, for some side pain I’d been having.

I was examined by a physician assistant named Andrew Moody who suggested an ultrasound. He was guessing a kidney stone.

But the images showed something worrisome.

“Questionable solid right renal mass,” the radiologist had written.

I was sent for a more definitive CT scan.

Now, Jan. 8, I’d been called back to the clinic to hear the results.

I drove there in a cold drizzle, knowing doctors usually use face-to-face for bad news.

Two medical pros go the extra mile and find my cancer

Andrew Moody came into the room. He’s tall, lean and 30 years old, yet with a mature air.

He projected calm but felt stressed inside. This was among the hardest moments he faces.

We chatted briefly, but Moody knew there is no good way to build up to it – the verdict simply had to be stated. Quietly and professionally, he did so.

“The CT scan is suspicious of a malignancy.”

I knew what the phrase meant and heard it that way in my head:

“You have cancer.”

At some point in the recent past, one of my own cells had mutated and begun to divide chaotically, growing into a malignant tumor on my right kidney.

Moody told me it was likely renal cell carcinoma – that’s what most solid kidney masses are. I’d be referred to a urologic surgeon.

For the first minute or two, I don’t think it sank in.

Then he said this:

The surgery might involve removal of the kidney.

For some reason, that hit me even harder.

“I’d lose a kidney?”

Moody said it’s sometimes the case, but assured me people live well with one.

In my previous visit, he had seen me as talkative and firing questions. No longer. I seemed lost to him now.

The meeting went 20 minutes. After I left, Moody had to pause in his office, collecting himself before going on to his next patient.

I walked outside to my car. It was just before 5 p.m., the moment the second part of my life began.

As I pulled out of the lot, a gray rain was still coming down.

I don’t remember much else about the drive home.

Three weeks later, Jan. 31, I lay anesthetized on an operating table at Miriam Hospital. A team of 10 were in the room, led by Dr. Dragan Golijanin, 57, the oncological surgeon.

He was two hours into the procedure, guiding small robotic scissors to cut his way to the tumor. The electrified blades cauterized vessels, and puffs of smoke inside me caused brief seconds of haze.

Dr. Dragan, as many call him, had traveled a circuitous journey to this moment. He went to medical school in what was then Yugoslavia, leaving in 1991 when the country fractured into war. As the bloodshed turned catastrophic, he moved his young family to Israel, where he had relatives.

Dr. Dragan spent a decade practicing there, then moved again to become a fellow at New York City’s legendary Sloan Kettering cancer center.

Seven years ago, lured by Brown and Lifespan, he settled in Providence. He now ranks among the most accomplished urologic surgeons in New England.

It took 15 minutes to remove the typical fat layer covering my right kidney. Then he saw it - the mass.

It had yet to be biopsied, but Dr. Dragan was sure of what he was looking at. It wasn’t uniform in shape. Parts of it were decaying. It was different than healthy tissue.

It was cancer.

Dr. Dragan performs around 150 such kidney operations a year, more than any surgeon even in Boston, but he still gets amped by each, especially this part - confronting the malignancy.

He stared for a beat at the tumor and told it in his thoughts: “You’re dead.”

Then, there in the operating room, he spoke out loud to his team.

“Let’s get this damn thing out.”

The pain, deep in my right flank, began last December as I lay in bed near midnight. It was unfamiliar – neither a cramp nor injury.

After an hour, it went away.

Maybe I’d slept on it wrong.

The following days, it was on and off. One night, it left me nauseous. I decided it could be shingles, the later-in-life return of the chicken-pox virus. I’d had it before – didn’t it cause side pain?

But it kept abating, and I’m quick to dismiss ailments that disappear. Plus, it was the holidays, with my three adult kids home – I didn’t want to hassle with doctors.

On Christmas Eve morning, it came back so intensely I was on the floor wincing. Then it subsided.

Perhaps it was time to have it looked at.

Had the kids been awake, with the pain now gone, I’d have shrugged it off. But they weren’t up yet.

I assumed an urgent-care clinic was best for showing up unannounced, especially on a holiday. I drove to the Primary Walk-In Medical Center.

I figured I’d be in, out and done.

Andrew Moody had drawn the clinic’s Christmas Eve shift that Dec. 24, 2018. He’s the son of an Air Force dad and a mom who had breast cancer when he was in middle school.

Those who cared for her made a difference – and made Moody want to go into medicine.

Moody’s first job as a physician assistant was at Roger Williams Medical Center, in a field I would soon find myself facing – surgical oncology. He assisted as doctors excised cancers of the pancreas, liver, thyroid and more.

Two years ago, he married and, to build savings, began working weekends at the Primary Walk-In. He liked the challenge of never knowing what would come through the door. Soon after, he began there full-time.

I told Moody I’d been having side pain. He did a brief physical.

A kidney stone, he felt, was possible. Or kidney infection - that causes side pain, too.

A malignancy, he thought, can do the same, but the odds were minuscule. In Moody’s two years at the Clinic, he’d never run into a single kidney cancer.

As he built a list in his head, I suggested shingles; I’d had it before. Moody told me he could prescribe for that, and did.

At that point, he could have moved on – other patients were waiting.

But he asked for a urine sample before I left.

That was the third leg of diagnosis – listen, examine, test.

I drove away with scripts, thinking: case closed.

But Moody wasn’t done. The Primary Care Clinic has a machine to test samples. In minutes, he had my result.

It showed microscopic signs of blood, called hematuria.

That changed his thinking. Flank pain, hematuria – likely kidney stone.

Moody still could have left it at that – kidney stones usually go away by themselves. Drink water and use painkillers.

But to assure nothing was missed, he wanted an ultrasound.

He caught me by cell as I drove home. He had already checked with Coastal Medical Imaging nearby - they could take me now.

I was impressed that he’d chased me down, but kept driving. My kids were up, his new diagnosis seemed right, and the pain was gone. No need for another test.

Then I realized I’d just passed the imaging lab. All right – get it over with.

Impatiently, I turned the car around and pulled into the Coastal lot.

Janine Daly, 28, ultrasound technologist, had me lie on my side on an exam table.

She lifted a plastic-handled probe the size of an electric razor and placed it on my right flank below the rib cage – ultrasounds don’t see through bone.

An image of my right kidney came up in shades of gray. She was searching for a stone but kept an eye for surprises.

Techs, she felt, should always be mindful of finding things they’re not looking for.

The first few passes showed everything normal, but Daly kept at it. She sees herself as the radiologist’s eyes. Even with a dozen-plus patients a day, she doesn’t let herself rush.

To be thorough, she scanned to the kidney’s edge and beyond. That’s when she saw something that wasn’t supposed to be there.

A mass.

Of the thousands of scans in her four years at Coastal; this was only the third or fourth renal growth she’d spotted.

Janine Daly kept her expression even. Her job is to never show alarm.

Soon she escorted me out, wished me Merry Christmas, then gave a heads-up to Dr. Lauren Florin, the radiologist on duty.

Daly hoped the mass would prove benign. She was sad to think what a difficult journey I would face if it wasn’t.

Soon after, Dr. Florin studied my images, suspected a malignancy and messaged Moody that I needed a CT scan to confirm.

I had spent Christmas Day relaxing at home, having no idea what was being found. A light snow gave brief hope of a white Christmas before it disappeared.

That evening, we ordered take-out from Jacky’s restaurant. My 27-year-old son is studying overseas and had to fly out the next day; the dinner was partly a goodbye to him.

On Dec. 26, I was asked to return to the Primary Walk-In, where Moody told me about the mass, and the need for a CT scan. His boss, clinic owner Dr. Constantine Vafidis, knew some providers might not have ordered an ultrasound for the flank pain I had.

Vafidis told Moody: “Good job catching this, brother.”

The days waiting for the CT scan were not easy. In the five months since this began, I’ve realized new cancer patients face a series of psychological cliffs. Sometimes for weeks, you are left on the edge, waiting for the next verdict.

This was my first cliff.

I didn’t immediately tell my kids about the ultrasound result. A dad’s job, I felt, is to protect them from such things.

Though maybe I wanted to protect myself. As you age as a parent, there’s a fear of trading places – your children taking care of you instead of the other way.

I wasn’t ready to think it could happen sooner than later.

Getting the diagnosis

At 1:30 p.m on Jan. 6, I walked into Advanced Radiology in East Providence for a CT Scan to explore whether I had cancer.

The next morning, radiologist David Cheng pulled up my images and had no doubt what he was looking at.

The mass on my kidney was solid.

It had blood flow.

It was malignant.

Cheng knew it couldn’t be fully confirmed until checked by microscope after surgery. But over 90 percent of such kidney tumors are renal-cell carcinoma.

Cheng took some final minutes to check the images of my torso for any sign of spread. That’s when he saw something that troubled him.

There were marks – lesions – on my pelvis. They could be benign, but he wasn’t sure.

He advised an MRI follow-up to see if it was metastasis -- if the cancer had spread to the bone.

The next day, Andrew Moody told me I had cancer of the kidney, and worrisome marks on the pelvis.

That night, I stayed clear of the web. I didn’t want to obsess, or even face it.

Then I got into bed. That’s when the mind goes where it will.

I wondered if this was the way I would one day die. Most of our lives we don’t know. Did I now?

If so, perhaps it was time to leave my job. I’ve heard people do that when facing mortality – travel; seize life.

But do they really? As I lay there, I realized it’s more about wanting to be at peace with who you are.

Which I wasn’t.

Did I build enough in my life, give enough, love enough? No, not always.

I thought about my failings; as a parent, friend, professional – the things I’d hoped to achieve but never did.

You can’t change past mistakes, I thought, but at least you can try to live better each day.

That’s where I was that first night; and still now.

A possibly terminal diagnosis does bring thoughts of a bucket list, but not overly so.

Mostly, it makes you want to live conscientiously.

The next morning, I finally went online -- and learned I’m nobody special.

Each day, 4,800 people in the U.S. find they have cancer - 1.7 million per year. In Rhode Island, it’s 6,500 annually, near the nation’s highest per capita.

Then I looked at kidney cancer.

Around 500,000 people have it, with 65,000 new cases each year and 13,000 dying of it.

I looked at survival rates.

The mass was 2.8 centimeters, a little over an inch. That seemed to put me in Stage 1, with more than a 90 percent chance of making it five years.

Yet that five-year marker threw me. It’s how remission is measured, but life is supposed to unfold for decades.

Suddenly, the horizon was shortened.

Then I read a detail that unsettled me more.

A common sign of kidney cancer is back pain below the ribs. That had been my telltale symptom.

The web told me such pain is not an early sign.

If renal-cell cancer causes that, it’s likely well advanced.

One of the first calls I made after the diagnosis was to my brother Douglas.

We talked about the most immediate threat – losing a kidney. I’d gone online and found Moody was right – even in early stages, the kidney is often removed.

Douglas and I talked of how you can live fully with one kidney, but it scared me. What if something happened to the remaining one?

Although upbeat on the surface, Douglas is a brooder in private. A friend of his knew someone who died of kidney cancer and told him my case looked bleak. Douglas didn’t share that with me.

Nor did he share how concerned he was about the marks on my pelvis. He’d spent more time than I Googling details and found prospects are grim when kidney cancer spreads to the bone.

He didn’t share that with me either.

When told you have a malignant tumor, the impulse is to look for a guru at some national center like Boston’s Dana Farber Cancer Institute. But a doctor friend of mine named Marty Miner, who specializes in men’s health at Miriam Hospital, told me Rhode Island has more world-class care than locals realize.

He knew many names for me but one, he said, stood out.

I should call Dr. Dragan Golijanin.

I dialed his office. He could see me in a week, fast for his schedule. But it left me on another cliff.

Could the cancer be cured? The kidney saved?

As the days to the verdict dragged on, I talked to other doctors I knew, including a urologist colleague of Dr. Miner’s named Mark Sigman.

He mentioned something surprising.

My flank pain was likely not caused by the cancer. It was from a kidney stone, which indeed had shown up on the CT scan. He was almost certain it was the cause. The mass was too small.

I joke that I’m now a fan of kidney stones, but it’s often like that – two-thirds of early renal tumors are caught by chance as doctors look for something else – abdominal pain, gallstones, spinal issues.

The timing of the flank pain was astonishing luck. A year earlier - the scans might have missed signs of a problem; much later, the cancer would likely have been far more grave.

I say “likely” because of what I learned after surgery.

Despite the small size of the tumor, I did not have the preferred Stage 1, as was assumed.

Or Stage 2 – a bigger tumor, but still self-contained.

I had Stage 3 - out of 4.

It had begun to spread.

Not long after my diagnosis, I knew I had to tell my children.

My older son Alex, 27, is in his third year of medical school in Australia near Melbourne.

I called and explained they’d found a mass on my kidney.

“Alex,” I said, “I’m afraid it’s cancer.”

I quickly added they’d found it early.

But his thoughts went to the worst outcome. What, he wondered, if it had spread? Was he about to lose his father?

As I talked, he considered deferring school for a year and coming home.

I told him I could lose a kidney, a second shock. What if my other kidney had problems?

He’d seen patients with kidney failure and knew it’s a tough road. He pictured me in dialysis for hours a week, no longer able to be active.

I assured him this wasn’t terminal, though I didn’t know if that was true.

Then I told him the best he could do for me was stay in his life.

Over the next days, Alex felt guilty as his routines went on – classes, meals, exercise. Shouldn’t life stop at such a time?

But of course, it can’t.

Over the next days, I was relieved the kids weren’t overwhelmed.

Perhaps, I felt, it wasn’t real to them because I didn’t have symptoms. Or maybe even adult children see their dads as invincible figures, able to withstand storms.

It turns out it was something else.

Alex said he decided not to show me how devastated he was, feeling I had enough on my plate without having to console him. He made himself put on a strong front.

But then he worried it could make him come off as less concerned. It also felt unnatural, trying to be the one his dad could lean on, instead of the other way. He wished there was a playbook on how to navigate this.

My daughter, Ariel, 31, who has a sensitive heart, also seemed to take it better than I expected.

But later, I asked if we could chat for this story about how it impacted her. She was sorry; she couldn’t talk about it.

That’s why she had seldom asked how the treatment was going. She said it’s too hard for her to face.

In some ways, even more than the cancer itself, I obsessed about losing a kidney. Would it make me feel less whole?

At times I was ashamed of such thoughts, knowing people courageously donate kidneys, and that countless cancer survivors have given up similar or worse - fertility, mastectomies, a lung, bladder, colon, limb.

But it’s where I was in those first weeks, dreading my own loss.

I slept poorly. Could the cancer be cured? The kidney be saved? What about the pelvic lesions?

Finally, on Jan. 16, eight days after hearing the diagnosis, I drove to Brown Urology’s office on Collyer Street, near North Main in Providence, to see Dr. Dragan.

He would be my surgical oncologist.

I was about to hear the verdict on what my cancer would mean.

Dr. Dragan strode into the room, a big man with a big spirit.

He would soon show me images of the kidney mass on a computer screen. I hadn’t seen it yet, and it took me aback.

I thought it would be a spot you could barely make out. But this – you couldn’t miss it.

Perhaps it’s because kidneys measure four to five inches, so a one-plus-inch tumor looks ominous, a quarter as big.

Instinctively, I leaned away from the image.

Dr. Dragan was the opposite. He couldn’t wait to get in there and face it.

He began with stunning news – at least to me.

He could save the kidney.

For what felt like the first time in weeks, I exhaled.

I would soon learn that even 10 years ago, I’d likely have lost the kidney. Back then, that was the standard for removing a tumor like mine.

The attitude, Dr. Dragan recalled, was simply, “It’s cancer, let’s take the whole thing out.”

It’s still a practice in many smaller areas and hospitals. That’s because it’s far easier to remove the whole kidney, called a radical nephrectomy. Snip a cord at either end and it’s out, the tumor with it.

But Dr. Dragan saw it this way: “Just because it’s easier for me doesn’t mean it’s best for the patient.”

Dr. Dragan was an early practitioner of this new “partial nephrectomy” approach. Almost 20 years ago at Sloan Kettering, he’d studied under one of the pioneers who steered medicine toward saving cancerous kidneys.

Today, Dr. Dragan keeps the kidney in almost 70 percent of his renal cancer surgeries.

He did say my own might have to be removed if the cancer proved more extensive than expected. But he’d only had five such surprises in his years here – about 1 percent.

Then I asked about the suspicious CT scan marks on my pelvic bone.

Dr. Dragan had looked at them. He didn’t think they were cancer – unlikely with a tumor this small.

But to be sure, we’d do the recommended MRI after the surgery.

He did say there are cases where cancer returns even after the removal of a mass like mine. But it’s unlikely. He put it at only a few percent.

That’s because the most common kidney cancer – eight of 10 cases – is renal-cell carcinoma, which seldom spreads if caught early.

It was assumed that’s the cancer I had.

That assumption would prove wrong.

An operation

On the morning of Jan. 31, Dr. Dragan Golijanin woke in his East Side home at his typical time, 5:30 a.m., arriving at Miriam Hospital an hour later.

He gowned up for his day’s first operation and was well into it by the time I got to Miriam at 8:30 a.m.

I changed into a johnny and was brought to a curtained-off room in the pre-anesthesia area. Nurses had just finished putting an IV in my arm for a saline drip when Dr. Dragan walked in.

As always, he had a smile.

“Look who’s here,” he said. “What’s up, Mark? How was your night? Did you sleep?”

He jumped to standard verification protocol: “What side are we doing?”

“Um – right side.”

“I agree.”

We chatted a bit, and then he nodded.

“Let’s do it. Let’s make you better – I’ll see you in a few.”

There in the holding area, I was given Midazolam to make me drowsy, then wheeled down the corridor to Operating Room 9. Dr. Dragan likes that room; he considers nine a lucky number because his countryman Nikola Tesla, the genius inventor, did as well.

A team of 10 was already there, the temperature set low to keep everyone’s senses keen. The anesthesiologist gave me Propofol. Seconds later, I was under.

They positioned me on my left side, with my right arm over my head like a swimmer, then taped my eyes shut to keep them from drying out.

The team washed my skin with chlorhexidine disinfectant, then waited three minutes for it to evaporate. It’s alcohol-based and the robotic scalpel, electrified to cauterize vessels, could spark it.

They covered me in blue drapes – even my head, leaving only my right abdomen open.

Then it began.

Dr. Dragan took a scalpel to start making five puncture holes. He cut through skin, then fascia, muscle and peritoneum, into my abdominal cavity.

Finally, he reached my internal organs.

But it’s crowded in there, so he had to inflate the space to see what he was doing. They put a tube through the puncture hole and pumped in three liters of C02 gas until I looked six months pregnant.

He went on to cut other holes for the main three tools – forceps for grabbing, a scissors-like scalpel for cutting, and a camera.

“It’s like the Lakers’ triangular offense,” Dr. Dragan says.

Each tool was on the end of a metal rod. They inserted them into me, then attached them to the hydra-like arms of a big robot that hovered above like a six-foot beige mechanical spider.

They were ready.

Ten feet away, Dr. Dragan sat behind a console – the brain of the robot. From there, he would operate each instrument with a joystick, guided by live video he watched with his eyes pressed into a viewing scope.

At my side, several on the team stood ready to assist with hands-on adjustments.

Dragan Golijanin gave the “go” command.

“Put the suction in and let’s start working.”

He leaned forward, took the controls, retracted my liver, and began to cut toward the cancer.

Dragan Golijanin had an idyllic childhood in old Belgrade near the banks of the Danube River, exploring its islands like a Yugoslav Huck Finn.

His grandfather was involved in carpentry, and young Dragan grew to love fixing things. When a doctor uncle pushed him toward medicine he was drawn to wanting to fix things there even more.

One afternoon at the University of Belgrade Medical School, a surgeon mentioned an upcoming appendix operation – would Dragan like to watch? He gowned up and they even let him participate, doing the final appendix cut.

It was an instant fix - physically removing disease so the patient could go home cured.

This, he decided, was what he was meant for.

An hour-plus into my operation, Dr. Dragan was now immersed in what most would see as alien landscape but to him was familiar terrain – the inside of the human anatomy. Basically, it’s his office.

He pushed part of my digestive system aside, and the duodenum down to expose the kidney.

It was covered, as all are, in a layer of fat. Slowly, guiding the robotic mini-scissors, he cut and peeled it away.

That’s when he first saw the tumor.

It was in a tricky spot to access.

“It was not easy to get there,” he would later say. It took arduous maneuvering, but he made it happen.

In some cases, he uses a dye that turns malignancies green to define their edges. He didn’t need to in my case.

The cancer was obvious.

He asked Dr. Paul Bower, a resident at Miriam Hospital, to put clamps on the blood supply leading in and out of the kidney. Soon, it turned from pink to pale.

The clock had started – they had 20 minutes or so before tissue would start to die.

But Dr. Dragan knew he had to balance speed and precision. One thing he never wants in the operating room is drama. Good surgery, he feels, is predictable, even boring to an outside eye – though for those involved, it’s always tense, with no room for missteps.

He marked the boundary of the tumor, adding extra room beyond it for a cancer-free margin.

He was now at the critical point. He appraised target. It was about the size of a quarter, though thicker. The sight of a malignancy always offends him.

He could see how it attached itself to the kidney, drawing sustenance, bent on taking it over and worse.

It was time to kill it.

Using the robotic forceps, Dr. Dragan began to slice around it. As he finished the final cut, he thought to himself: “You get a red card.”

That’s when he said, “Let’s get this damn thing out.”

He grabbed the mass with the robotic forceps and pulled it from the kidney. Carefully, he put it in a small plastic bag they’d inserted into me to make sure no malignant cells escaped.

The excision left a crater on the kidney. Dr. Dragan studied its margins – it looked good, no sign of tumor tissue. He began suturing it closed with one continuous thread, cinching it like clapping hands coming together.

He put the layer of fat back over the kidney as if zipping a jacket, removed the retractor holding the liver aside, undocked the robot and turned on the lights.

They closed the fascia, or connective tissue, and put staples on four of the punctures, leaving the fifth for a drain. The anesthesiologist turned off the gas and took the breathing tube out.

Soon, I was rolled to the post-anesthesia care unit. Two hours later, hopefully free of cancer for the first time in perhaps a year, I was on the recovery floor.

The tumor would now be sent to be biopsied. All expected the pathologists would confirm two things.

First, that it was slow-growing, garden-variety renal-cell carcinoma, called RCC.

Second, that it was Stage 1, meaning no spread.

No one in that operating room suspected it at the time, but neither was true.

Nights in hospitals can be long, and restless. I lay awake wondering how the tumor got there.

Nobody, including Dr. Dragan, could say. With exceptions like smoking and asbestos, a cancer culprit is rarely certain in each case.

But it weighed on me. Some toxic agent? Diet? A bad gene?

One iffy link gave me pause: overuse of NSAIDs like aspirin and ibuprofen. I’ve been an Advil junkie for decades, taking way too much for exercise soreness.

I told myself it was a factor - you want to think you can control it.

But perhaps it was just a truth of human biology – that often, cells randomly mutate into malignancy.

I was told patients should walk after abdominal surgery, so I began circling the floor’s corridors. By the time I got home on Day-3, I was doing a slow mile on Blackstone Boulevard’s central path.

But I was on a cliff again, this time waiting for the pathology report. What would the microscope find?

In two weeks, I would see Dr. Dragan for a post-op meeting. That’s when I would hear.

I told myself to stay confident. There was 90-percent chance the tumor, being just over an inch, was Stage 1 RCC with no spread.

It had to be that.

On Feb. 12, a cold day with snow on its way and a wind-chill in the teens, I drove back to Dr. Dragan’s office on Collyer Street.

He greeted me with his usual positive energy.

But his next words weren’t what I expected.

I’ll always remember the phrase.

“We’re not done yet,” he said.

And then:

“We have more work to do.”

He went on: “It’s very good we operated.”

It turns out I did not have garden-variety renal-cell carcinoma.

“It came out as a rare cancer,” Dr. Dragan said.

He gave it a name.

There are two versions of Papillary, with a profound difference between them.

Type 1 is more common - and preferable - with low recurrence if caught early.

Type 2 is pernicious, with a worrisome prognosis.

The pathology found I had Type 2.

The chances of that were only a few percent - a rare worst-case typing that’s only seen by the Miriam urology team a few times a year.

Dr. Dragan’s tone was positive, as if to say, “I’m on this,” - but his words were direct.

“This Papillary Type 2,” he said, “is known as a cancer that can be very aggressive and very fast growing.”

I learned there could be a clear cause after all.

Type 2 often comes from a bad gene. He told me I’d soon be sent for genetic testing to confirm it.

The gene – if I indeed had it - could lead to the cancer showing up elsewhere in my body, so I would need screening scans every three months.

In particular, he wanted an MRI soon to check the marks on my pelvis.

He also wanted a chest CT scan, since Type 2 is known to metastasize to the lungs.

Then, more bad news.

The cancerous mass was not self-contained.

“It was invading more than a usual tumor of that size would do,” Dr. Dragan said.

This, he told me, meant it wasn’t Stage 1, even though it was a smallish 2.8 centimeters.

Nor was it Stage 2, which means a bigger tumor over 7 centimeters, but no metastases.

I was Stage 3 – the designation when there’s any spread. Some cells, he said, had begun to invade surrounding tissue.

He stressed all of it was removed. Still – I was Stage 3.

I asked what would have happened had we not caught this.

Regular kidney cancer, he said, can grow slowly. But he’s seen a Papillary Type 2 tumor double, triple and more in six to 12 months – and at times metastasize.

The pathology meant I would need another doctor. A medical oncologist.

It would be Dr. Anthony Mega – he and Dr. Dragan are co-directors of urology-oncology at Lifespan’s Cancer Institute.

The meeting had gone a half hour, and I knew he had a full waiting room.

“What,” I asked, “is the likelihood this cancer could show up somewhere else?”

Dr. Dragan paused. Clearly, he didn’t want to answer.

“Let’s do this MRI and the CT scan,” he said.

I thanked him and headed back to the car.

For several minutes, I just sat there in the parking lot.

Some answers

Dr. Anthony Mega’s phone buzzed – it was his colleague Dragan Golijanin.

Mega was rushing between appointments, but he’s learned not to ignore calls from Dragan.

“If I don’t answer,” Mega says, only half-jokingly, “he’ll yell at me.”

“Tony,” said Dragan, “I have a patient you need to see. And I need you to see him soon.”

He says that often. If a cancer could spread, he doesn’t waste time.

Mega felt the same. He knew a cancer diagnosis leaves people frantic for answers.

Were he in my shoes, every day would feel like a month.

Oncologists’ hours start early and run long, but Anthony Mega was used to that.

Now 57, he grew up in Mount Pleasant, his dad the owner of iconic Crugnale Bakeries. Mega began working there at age 14 in 1976, rising at 3 a.m. summers and holidays to bag bread at the Valley Street plant.

A science kid, Mega went from Classical High to Brown, then Dartmouth Medical School, tracking into its noted oncology department. The patient relationships were as intense as the work, sometimes heart-breaking, always rewarding. He’d found his path.

Back at Brown for an oncology residency, Mega was soon on the front lines of the 1990s AIDS wars, fighting immune-deficiency sarcomas. By the early 2000s, in one of medicine’s victories, AIDS went from an acute disease to a managed one.

Mega then found himself recruited to a new Miriam Hospital urology team, a big group of specialists created to give patients any expertise they’d need.

I now needed an oncologist.

On the morning of Friday, Feb 15, I went to get a CT scan of my chest. The following morning, I spent 40 minutes inside an MRI tube getting images of my pelvis.

I tried to read the faces of both techs, but wasn’t able to.

I was unnerved by the thought that Type 2 often spreads to the lungs. I began taking deep breaths in search of a sign.

Days later, I was alone in my study when Dr. Dragan’s name came up on my phone. He had given me his cell, as he does to most patients.

For all I knew, he was between surgeries; he’s prone to call patients at any time, especially with hopeful news.

He had some now.

He wasn’t convinced I had the aggressive Type 2 carcinoma. He felt it could be the better Type 1 - if one can use the word “better” about cancer.

Some tumors, he said, are hard to tell apart. They have properties of both. Mine did.

But Dr. Dragan’s gut told him my cancer was not behaving like the pernicious Type 2.

It hadn’t spread widely. He’d seen it eye to eye, and aggressive cancers often shout at you. This tumor didn’t.

He sounded almost offended that it was purporting to be Type 2. This had been difficult surgery, yet he’d gotten the mass out and given me hope of my life back. How dare this cancer turn out to be more ominous than expected.

It was as if he wouldn’t stand for it.

He wanted the sample to get a second reading. He told me he’d have it sent to Sloan Kettering in New York City.

My brother Douglas flew in from Chicago for the meeting with Dr. Mega.

I’d told him he didn’t need to bother, but he knows I’m the kind who doesn’t ask for help even when I need it.

Hearing the prognosis for an aggressive cancer would not be easy. Plus, the pelvis MRI hadn’t yet come back.

Neither of us was optimistic. How else could one explain those marks?

I booked a table at the Capital Grille, with jokes between us about a last meal. The hostess was seating us when my cell rang.

Dr. Dragan.

I went to an alcove to take the call.

His voice was upbeat. He’d gotten the reports on my CT scan and MRI.

Both had cleared me.

There was no spread in the lungs, and no cancer on the pelvis – the marks were bone islands, a benign effect.

It was after 7 p.m. I thanked Dr. Dragan for calling at that hour.

“Of course I’m going to call,” he said. “You’re my patient.”

Back at the table, I told Douglas the news. But even as we celebrated, I was back on another cliff.

What would be my odds of staying clean of cancer in the next months or years?

Dr. Mega would tell me the next morning.

The meeting was in Lifespan’s Cancer Institute, next to Miriam Hospital. A staffer brought us to an exam room. Soon after, Dr. Mega walked in.

Like Dr. Dragan, he has a reassuring air, though more quietly.

He began by asking how I felt. He makes a habit of probing that way.

He once had a kidney cancer patient who mentioned knee pain – easily dismissed as an ache or strain. But Mega ordered tests and found it was metastasis.

I told him I felt well, then went to my main question.

What were the chances this would recur?

Mega believes in candor, so he didn’t hedge.

“Probably a 40- to 50-percent possibility.”

What?

Douglas kept an even face, but would later say the number stunned him. He thought to himself, “My God.”

“That’s pretty sobering,” I said.

Seeing I was deflated, Mega turned to a computer to reappraise my scans. He noted the tumor seemed to be away from big blood vessels, which could make recurrence odds a bit lower - more like 30 to 35 percent.

That still seemed gloomy.

What, I asked, if it does recur? Would that mean chemo or radiation?

No - those are ineffective against kidney cancer. Instead, he said, they would use immunotherapy.

“Cancer cells have found a way to cloak themselves,” he explained. “Immunotherapy opens that curtain up.”

I was encouraged, but then Mega mentioned immunotherapy’s effectiveness.

Around 30 percent.

That’s all?

I realized the irony – a 30-percent recurrence rate seemed shockingly high, a 30-percent cure rate low.

Finally, I asked about the reading we were waiting for. If Sloan Kettering called it Type 1, would that change these odds?

It would be welcome, said Mega, but it would still leave two conflicting pathology readings.

So he had one more idea.

He planned to take the exceptional step of sending my sample out for DNA testing – rarely done, but worth a try, given how unclear my sample was.

The meeting went over an hour. As we said goodbye, Dr. Mega offered me his cell number in case I had a sleepless night and needed to talk to someone.

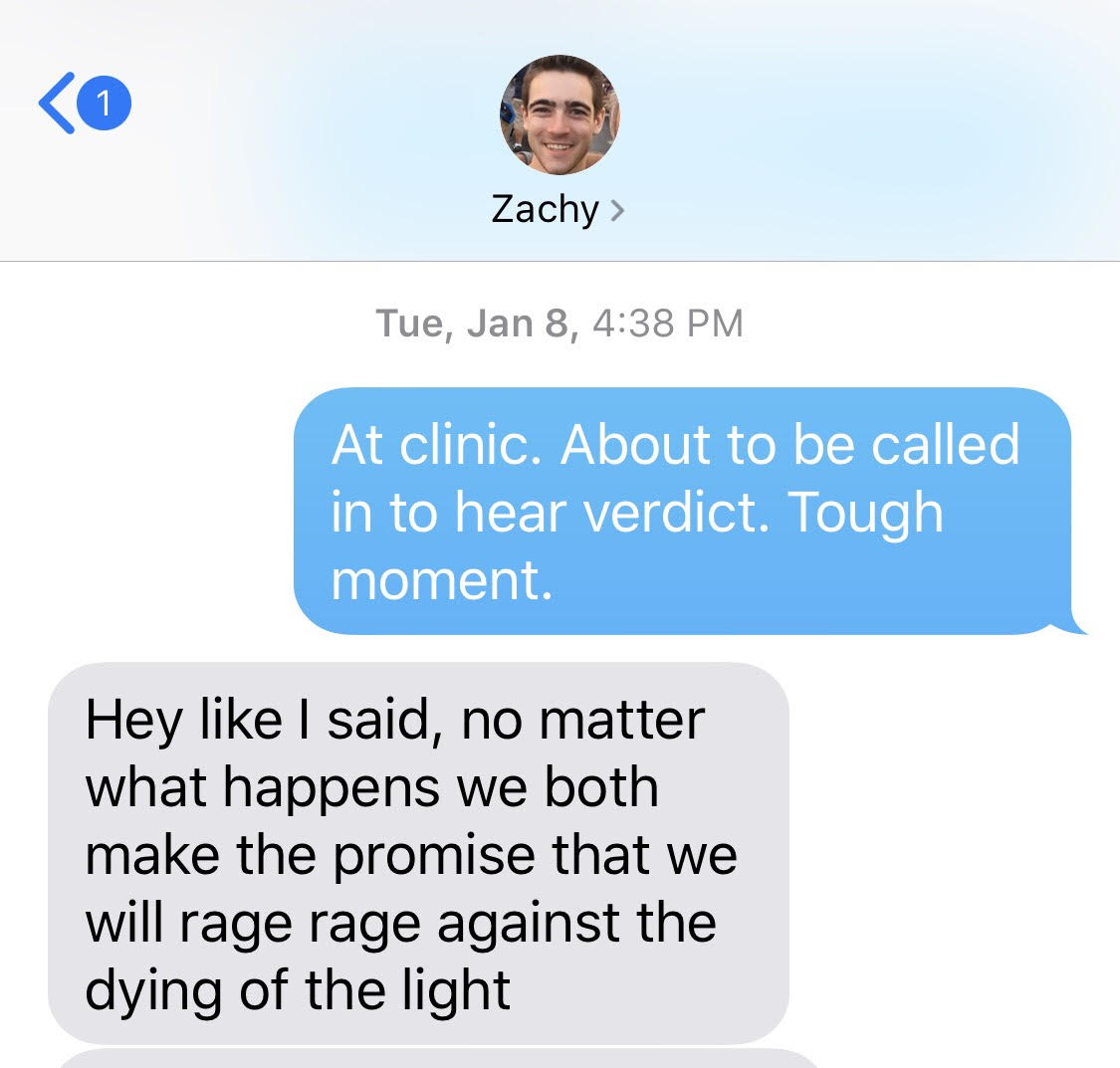

My youngest, Zach, 25, has been living at home between apartments, so at first I felt I didn’t need to “interview” him for this article. I’d just draw from the times we talked of it.

Then I realized we barely had.

I asked why he hadn’t brought it up more. He gave me the same answer as his brother.

“I wanted to put on a brave face for you.”

Zach remembers when I told him the diagnosis. He worked a 4-to-midnight shift at his Boston job and wouldn’t be home until I was asleep. So I let him know mid-evening.

He reminded me I did it by text.

I suppose I didn’t want to interrupt his work – but a text? What a bad choice. It left him alone with it, leaving his office early, walking alone in the dark along Boston’s downtown waterfront.

After surgery, Zach remembered being at my side as I circled the hospital corridor. He was struck by how slow I was, and fragile, leaning on a walker.

This, he thought, is what life could be like if the cancer recurred – his dad in hospitals, moving gingerly down the corridor.

I asked him if I should have handled things differently – with more heart-to-heart talks.

“No,” he said. “I didn’t want you worrying it was weighing me down. You had enough going on.”

I, in turn, didn’t want to burden Zach. I was trying to protect him and he, me.

But I’m the parent. He was following my lead.

It was the wrong lead.

His father had cancer – I should have checked in with him more.

I didn’t.

I feel I failed him.

I was at home when Dr. Dragan called. It was the evening again.

He had gotten the second pathology results.

Great news, he said - Sloan Kettering felt it was the “preferable” Type 1.

It was still a mixed sample, he said, but if Type 1 was in there as well, it should behave that way, with a much lower chance of recurrence.

I’d stepped back from one of the biggest cliffs.

I sent a nod of relief skyward – then realized the irony of that.

I’d gone from being distraught at having cancer to being grateful for the version of cancer I had.

A few weeks later, Dr. Mega called.

He said the genetic reading had come back.

It, too, was hopeful for Type 1.

He explained the test doesn’t actually determine the type – it’s that I didn’t have any genes that would have caused Type 2. That argued for Type 1.

He told me I would still remain in his care, getting a first scan in three months, then every six months or so.

In time, if there’s no recurrence, it will be every year.

I did not celebrate the “Type 1” readings the way I expected.

Partly, I think, it’s that cancer’s many cliffs leave you emotionally spent.

But my case also may never have complete clarity.

And even if it is Type 1 – which is perhaps likely – well, that can recur too.

Nights, when I’m unable to sleep, it’s where my mind often goes. Are there rogue cells in a lymph node somewhere? A lung?

I wonder if it’s how soldiers feel as they wait for an approaching enemy, not knowing when, or if.

On many mornings, as I stand before the mirror, I’ll pause to look at the small scars from the surgery.

They are stigmata of sorts, marking the two halves of my life - the one before cancer and the one after.

They are reminders of the body’s fragility, but also, I tell myself, of its resilience.

Mostly, though, the scars bring something else to mind – the medical providers we so often take for granted.

I was saved from cancer’s spread by the skills of a surgeon, but just as much by a physician assistant, an ultrasound tech and dozens more I never met but were part of my care.

They gave me hope of my life back.

That is what I think of – or rather who - as I look at the scars.

Then I put on my shirt and begin a new day.