Black students face achievement gap in Volusia County

Compared to their white peers, black students in Volusia County schools are less likely to have a teacher who looks like them.

They are suspended from school more often.

They are less likely to enroll in gifted and advanced courses.

They perform lower on standardized tests.

And they are less likely to graduate.

The 10,000 black students in Volusia County walk into schools against odds that are outside their control — odds that highlight structures that are supposed to help them succeed, but in fact can work against them. Differences in educational opportunities for those students breed a difference in ability called the achievement gap.

Volusia County has put in place a handful of efforts to overcome these obstacles.

The district employs two minority specialists. It completes an annual equity report that one School Board member called “disheartening.” It focuses on building relationships in some schools as a way to prevent bad behavior. And as of this year, it gives equity training to newly hired teachers. Current teachers must access optional online training materials about overcoming bias in their free time, without compensation.

Experts say it’s not enough.

“As much as that’s a good effort, it’s a very small effort for a very massive problem,” said Rajni Shankar-Brown, an associate professor and chair of social justice education at Stetson University.

The real focus should be on closing these gaps as soon as possible, according to three national experts interviewed by The News-Journal who summarized what decades of research have shown.

The opportunity and achievement gaps plague almost every district in Florida and the nation. But for a district like Volusia County — where its leadership wants so much to earn an A rating from the state that it fired its last superintendent and has brought in a new one — leaders spend little time discussing strategies to close the gap between white students and students of color.

[READ MORE: Volusia County schools aim for an A, but face obstacles Florida doesn’t count]

These students’ lagging performance is often chalked up to poverty, something outside the school system’s control. In conversations with teachers and district officials, The News-Journal found that race is often excluded from the dialogue.

Volusia teachers union president Elizabeth Albert said that’s not OK.

“It’s infuriating, because at the end of it all, the grown-ups will be fine,” she said. “And the children will be lost.”

It comes down to what adults assume about children, explained Karin Chenoweth, a writer-in-residence for national nonprofit Education Trust who chronicles what successful districts do to help students of color achieve more.

“The underlying problem is that some educators have internalized the idea that African American kids, kids in poverty, are incapable of learning at higher levels,” she said. “Then they’re not working on, ‘He didn’t learn this, now what do I do?’ Instead it’s, ‘He didn’t learn this, I guess he can’t.’”

[READ MORE: Volusia County School Board approves $205,000 salary for new superintendent]

New Volusia County Superintendent Ronald “Scott” Fritz began work last week. His arrival gives the district an opportunity to shift its focus toward strategies that will help the students who need it the most — and Fritz isn’t shying away from the challenge of the achievement gap.

“It’s fairly common, but it should not be accepted,” he said. “There have to be some intentional efforts to make sure that gap goes away.”

Understanding the gaps

It’s easy to see racial disparity in student test scores. Gaps in performance exist for Hispanic and mixed-race students too, but the gap between performance for white students and black students is largest.

In 2018-2019, there was a 30% gap in the pass rate on the standardized language arts exam for black and white third-graders in Volusia County. Where almost 70% of white students and 80% of Asian students passed, roughly 40% of black students, 50% of Hispanic students and 60% of mixed-race students passed.

There were similar racial disparities across math and language arts scores for all grade levels in the school district.

Asian students are the exception among students of color, often outperforming all of their peers. The number of Native American and Pacific Islander students in the district is so small that data is not always available for comparisons.

Then there’s the graduation rate. In the 2017-2018 school year, 82% of white students graduated. But the rate was 10% lower for black students, 9% lower for Hispanic students and 7% lower for mixed-race students. It was 14% higher for Asian students.

Data like this quantifies the achievement gap: White and Asian students are doing better in school than their peers of different races.

But other metrics show disparities that point to a difference in the chances that white students get compared with their peers. Called opportunity gaps, these are examples of institutional racism — the structures that experts say allow for racial inequities within systems of power.

In Volusia County last year, 57% of students were white and 16% were black. But 81% of the teaching force was white and 9% was black.

Meanwhile, 32% of out-of-school suspensions were for black students, and black students accounted for 30% of those in classes for children with emotional and behavioral disorders.

But black students made up just 5% of gifted students last year, compared to 16% of all students. The majority of gifted students, 75%, were white.

None of these disparities are unique to Volusia County. In districts nearby and around Florida, students of color face similar gaps.

“There are very few effective school systems, and there are no large school systems that I’m aware of, that have substantially closed the gap,” said Jeff Howard, founder of the Efficacy Institute, which works to break the generational cycles that allow gaps in performance to continue.

“You come to understand the problem is not with the kids. It’s in the heads and practices of the adults that are working with the kids,” he said.

But the adults who are working with the kids in Volusia County tend to believe this isn’t an issue of race. Tim Egnor, the interim superintendent who led Volusia for the last six months and has decades of experience as an educator, argues it’s more about income disparity.

“It’s almost directly proportional to poverty,” he said. “You’ll notice that students who come from poor or poverty-stricken families ... they typically have not had the learning experiences that wealthy families can afford.”

It’s true that in Volusia County, students who are economically disadvantaged perform lower on standardized tests than their more economically advantaged peers — similar to the differences between white and Asian students and students of color.

But here’s what else we know: studies show that even when comparing students of different races who have the same household income, students of color tend to perform lower in school. And there are racial disparities within socioeconomics, meaning race is often an indicator of poverty level, too.

“You can’t have conversations about poverty without also having conversations about race,” Stetson’s Shankar-Brown said. “They’re just very interwoven aspects, where if you’re going to address these things with integrity you have to be open to seeing these complexities and the intersectionality of these critical issues."

That’s why the solution, experts say, is two-fold. If educators believe their students can’t achieve — whether because of their race or because of their income level — they don’t try as hard to teach them. And if schools believe it’s not their role to help level the playing field for children early on, the gaps persist.

What the experts say

Something called “implicit bias” informs how people see this entire topic. Those are the biases that we all carry with us, that subconsciously affect our attitudes about people and things based on preconceived notions about race, ethnicity, age and appearance. When educators bring those biases into the classroom, that’s where obstacles for students of color that exist in the rest of the world can appear in education, too.

“On some level, they think that gap is natural and to be expected and they don’t think they can do anything,” said Howard from the Efficacy Institute. “(Superintendents and classroom teachers) are good people with good intentions, but since many don’t really believe it can be done, they gave up years ago actually trying to make it happen. And they don’t hold themselves accountable.”

Take Shania Evans. She struggled with math in school. But as a black girl at Deltona High School, she felt like she was overlooked. She saw her teacher offering one-on-one help to other students, but not to her or students like her.

“You ask for help, but there’s not really any help there,” she said. “Not at all.”

So she stopped going to algebra, and Spanish, and biology. Then she and her friends started having trouble with another group of girls. She said she told a counselor about the situation and asked for help, but didn’t feel like he listened. Then, the girls got in a fight.

And after that Evans didn’t go back to school. At 16, she did virtual school at home, but she stopped after a few months. At 17, she became pregnant. She never received her high school diploma.

But what if her teachers had reached out to her and offered extra help?

“I probably would have graduated,” said Evans, now 20.

Shankar-Brown explained that school systems rarely take the time to get to the depth of the issues facing students like Shania Evans.

“What happens often is school districts might do a half-a-day workshop, or a school might do one faculty meeting where they focus on (bias),” she said. “It takes a lot of deep, reflective, inward work to dismantle and break down a lot of things like bias. If you’re trying to address gaps, investing in this sense is fundamental.”

She cited school systems in Illinois, New York and Minnesota that are beginning to implement comprehensive bias training and are starting to see results, but concedes that some research shows the training can be ineffective if not implemented correctly and continuously.

Chenoweth said such training is not a cure-all on its own. Instead, she said it’s about setting expectations at the highest levels that improving achievement for all students is something that will be a focus.

Howard agrees: leadership in the district must decide to make it a priority.

“The first step is to pull your cabinet together and say, ‘This is what we’re gonna do. Now, let’s work out how the hell are we gonna do it,’” he said.

After making it a point of focus, it becomes about educating young children — particularly in reading instruction.

This is where socioeconomic status really comes into play. Children learn to read through a mix of phonics instruction and vocabulary building. Students from wealthy families and students from white families tend to start school with a bigger vocabulary base, Chenoweth explained, because they’ve had access to more early educational opportunities.

“Once you have vocabulary and background knowledge, it’s easier to pick it (reading) up,” she said, if it’s coupled with explicit instruction in connecting sounds to letters. But she emphasized that no matter what, reading is complex for most children to understand.

“If you don’t have a lot (of vocabulary and background knowledge), it’s harder,” she said. “Your working memory is so taxed just by words on the page, you never really get to comprehension.”

[READ MORE: Unlike Volusia, top-rated school districts have textbooks for elementary schools]

By the time children get to elementary school, the clock is racing for struggling students to catch up to their peers. Students who are not proficient in reading by third grade have a much harder time getting on grade level. Instruction in phonics and comprehension continues through fifth grade but after third grade, students have to read to learn material in other subjects. And if they can’t comprehend what they’re reading, they’ll begin to fall further behind.

It’s a conundrum that starts outside of the school system, but could be fixed within it.

“You have to marshal the full power of schools in order to close achievement gaps,” Chenoweth said. “If you don’t, you will simply replicate the socioeconomics of the kids.”

What the district is not doing

The kind of training Shankar-Brown talked about, about overcoming implicit biases, doesn’t really exist in Volusia County schools. Starting this year, new Volusia teachers go through a 2-hour equity training. For existing teachers, similar training is available, but it’s not mandatory. And neither option is as comprehensive as Shankar-Brown was describing.

Egnor said that’s because professional learning time for teachers is already tight, and as schools try to accommodate more and more outside of just academic material — like increased security, mental health and an ever-growing list of legislative mandates — there’s little time left over for more training.

When it comes to training for teachers in Volusia County, the focus is on how to offer tiered instruction. Teachers learn to identify groups of students based on their skill levels, and provide more support for the students who are struggling. It’s a tough skill to learn, Egnor said, made even more difficult by teacher shortages and high turnover rates.

“There’s a discrepancy between groups of students, and our job is to provide what each of those students need,” said Desiree Rybinski, an elementary language arts curriculum specialist. “If there was a panacea for that, we would all be on it. But none of us have found it yet, so we just go back to good, high-quality instruction.”

Chenoweth said that’s what should be happening — until data shows gaps in achievement persisting. Then something must change.

In Volusia County, gaps in test scores have remained almost the same over the past five years.

That’s part of why Egnor and Fritz both pointed to early childhood education. It’s an area in which Florida, and by extension Volusia County, typically struggle.

There’s a free voluntary pre-kindergarten program statewide that compensates providers, including the school system, to educate 4-year-olds. Almost 80% of Florida 4-year-olds participate, according to the 2018 State of Preschool report from the National Institute of Early Education Research. It showed that Florida early education programs had the second-highest accessibility rate for 4-year-olds in the U.S. — but it was 41st in preschool spending.

A state-required readiness exam showed that in 2017-2018, 53% of Florida kindergartners were prepared to start school — meaning about half of kindergartners were not. For children who attended VPK, the readiness rate was only slightly higher, at 58%.

[READ MORE: Nearly half of Florida’s children are not ready for kindergarten]

“My belief is that a quality VPK program should be putting kids out not just ready to read, but actually reading,” Fritz said.

Last year, Volusia County had almost 4,500 kindergartners. Most of them took the readiness exam, and 55% passed. The district offers VPK at 21 schools around the district, and taught 1,000 students last year. Most children attend VPK at a non-school site, the preschool report stated.

Rybinski, the district’s language arts specialist, said there are no specific strategies to help catch up students of color, particularly black students, who they know tend to be behind. Instead, teachers must make sure those students are engaged in the strategies they’re using for the whole class.

Paulette McKibbins-Shed, the executive vice president of instruction for the Volusia County teachers union and a consultation teacher at University High School, wondered why there are no specific strategies for them.

“If you know you’re dealing with a population of students that have the possibility to come in with a deficit,” she said, “you ought to have the resources readily available not only to address the deficit but deal with students where they are and move them up to where they need to be.”

What the district is doing

Instead of the areas that experts in the field say would make the most difference, district leaders put their energy into two main things: increasing access to advanced classes and reducing disciplinary action. They’re relatively new focuses, and the two things that come up time and time again when officials are asked what they’re doing to close the achievement and opportunity gaps.

Before a few years ago, “there wasn’t really a strong focus” on making sure students were accessing high-level courses, explained Director of Student and Government Relations Amy Hall.

She said school counselors and principals were looking at achievement among students of color, but district-wide it wasn’t a focus. Now, she works with two district employees to tell families about their options and encourage students of color — specifically black males — to enroll in advanced classes.

“There’s a huge focus on graduation rates and improving those numbers. However, what we find is that in our elementary schools, there needs to be an even more aggressive campaign to close the achievement gap,” said Albert, the Volusia County union president. “The district-level decision makers need to make sure that when they’re focusing on moving kids academically, they start where the kids start. In elementary schools.”

There’s been some progress on this front. The number of black students enrolled in AP, IB and the Cambridge program has doubled since the 2014-2015 school year — but they still made up just 12% of those programs last year, even though black students make up 16% of the overall student population. Last year, black students made up 8% of the students who were dual enrolled in high school and college courses, although 50 more black students were in the program than in 2014-2015.

Those numbers weren’t good enough for the district’s longest-serving School Board member, Ida Wright — who called the district’s annual equity report “disheartening.”

“There’s nothing spectacular that we have done,” Wright said about the district’s efforts to close achievement and opportunity gaps. “It will come to a point that you have to decide what’s more important. And nothing should be more important to them.”

Additionally, there’s been a push in Volusia County to start teaching students about emotions and behaviors, as well as academics. The theory is that by building relationships with students, teachers can begin to address their non-academic needs and reduce how often students act out.

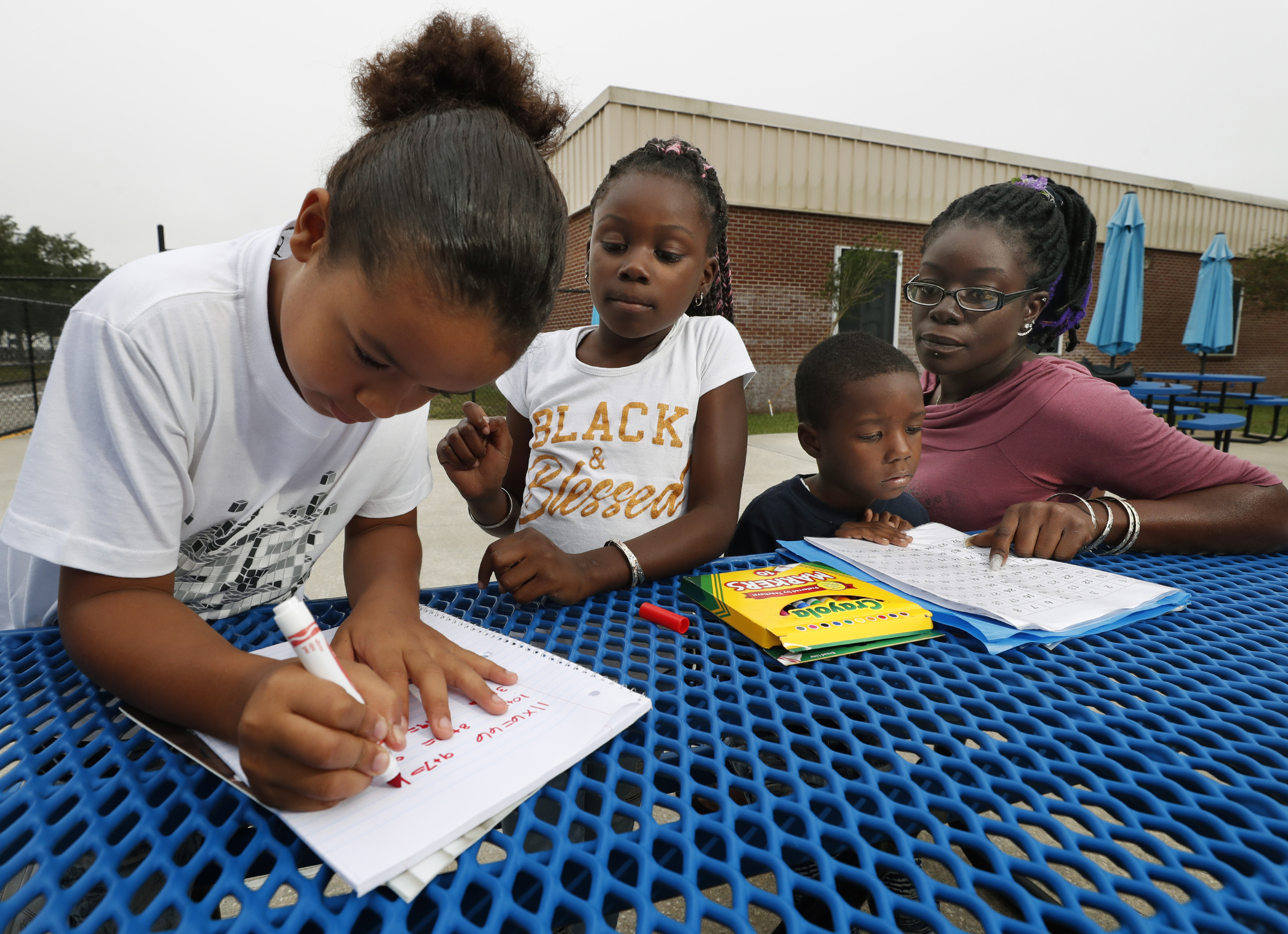

It’s supposed to cut down on the high suspension rate for black students, who disproportionately face discipline for their behavior — like Misessence Cross’s family.

[READ MORE: Volusia schools look to cut down on high rate of suspensions]

After escaping two relationships she said were abusive, 34-year-old Cross and her three children were homeless, couch-surfing with friends and family until just a few weeks ago. But thanks to the help of officials at Palm Terrace Elementary, they have temporary housing at Hope Place in Daytona Beach.

Cross said she works hard to make sure her children are getting support at home. She maintains a strict schedule for them no matter where they are, asks them about their day, reads with them and makes herself available to the school whenever she needs to be. But she also believes that over the course of their education, their race has impacted their experience.

Her youngest son, a kindergartner, was recently taken into custody for a mental health evaluation under the state’s Baker Act for threatening a teacher. And her oldest son, a fourth-grader, has been suspended 13 times since he started school.

“I do feel like there is a downside toward African Americans versus white children. I feel like sometimes there’s not enough patience for the black children,” she said. “They’d rather suspend them or kick them out versus working with them and helping them, like they would do with white children.”

The district is hoping to reduce the number of times suspensions occur, but data to show such progress has yet to be made available.

Suspensions have been a focus for F.A.I.T.H., a Daytona-based organization of religious congregations that tackles social problems in the community. The group’s leaders asked the School Board last year, not for the first time, to reduce suspensions by half over three years. They’re still waiting to see the data that would show if any progress has been made.

Shankar-Brown said despite work like this in Volusia County, there’s more to be done.

“Addressing gaps requires an honest examination of disparities, including reflecting on current systems and practices that unfortunately maintain and or perpetuate issues, even those that may appear well-intentioned.”

Resources

Test your implicit bias by Harvard University — A test to reveal your own implicit biases on a variety of subjects. Taking the test means you also participate in a project by researchers looking to understand those biases. You can also just get some information about bias.

The 1619 Project by The New York Times — A series of articles that reframe the country’s origins around slavery, and the lasting impacts it had on our society today. A PDF of the print version of the project is available through the Pulitzer Center, along with a guide for teachers who want to incorporate the issue into their teachings. There’s also an accompanying podcast that covers the same material.

Seeing White by Scene on Radio — A podcast about what it means to be white, and how it creates systems of power that still exist today.

Miseducation by ProPublica — A project that examines racial disparities in educational opportunities and discipline, from 2018. Use a searchable tool to examine schools and districts across the country. Read the related story from ProPublica and coverage from other news outlets using the data to examine their own communities.

The Educational Opportunity Project by the Stanford Center for Educational Policy Analysis — Explore national data on achievement and opportunity gaps, and find more information about what works to make education more equitable.

Being intentional

Shania Evans feels like when she was in school, her teachers didn’t believe in her. Now 20, she’s hoping to finish her diploma through the Chiles Academy for pregnant and parenting students. She thinks maybe, someday, she’ll own her own business, become a nurse, or be a lawyer.

It’s an opportunity she’s making for herself.

Incoming Superintendent Fritz is hopeful about Volusia County’s ability to begin closing the achievement gap.

“This is an area that I’m extremely passionate about, this is why I do what I do. It’ll be a big push,” he said. “Sometimes adults are hard to get to that point, but I’ve seen enough evidence that adults believe in kids and can move kids to excel.”

Evans hopes so. Her son is 2 now, and she’s expecting her second child soon. A girl.

“I hope they graduate on time and they get to attend prom and all that. That’s something I didn’t really get to do, that I looked forward to,” she said. “I just hope they receive all the help they can receive.”

This is the first in an occasional series of stories from The Daytona Beach News-Journal about the intersection of race and education.