Landing

Style Sheet

Navigation

Intro

Unmasked

Mark Rine became a firefighter because he wanted to save people. In the end, that job could also be what kills him. Rine has cancer. This is a story about firefighters who are dying of cancer more often than in burning buildings, and of one dying man who is dedicating the time he has left to saving his fellow firefighters from the same fate.

Don't miss the next chapter: Sign up for emails

Chapter 1

No one warned Mark Rine that while he was saving others, he was killing himself.

The bad habits that would ensure the firefighter’s death sentence started with his very first fire in 2007.

Rine was supposed to help set up the ladder, but he ignored his orders, grabbed the hose and charged into the burning two-story brick house.

The rookie firefighter trudged through thick black smoke. In seconds, he was covered in soot. His head throbbed, but he moved on.

Once he and the other Columbus firefighters from Station 23 extinguished the flames, they slogged back between fallen lumber and smoking furniture to make sure fire wasn’t hiding behind the walls.

At this point, Rine was wearing only a T-shirt and his heavy-duty pants, exposing his skin to chemicals. Instead of putting his air mask back on, he followed the older guys’ lead and covered his nose with the hood that covers his head and part of his face.

By the time the trucks cleared the scene on the Far East Side of Columbus, black mucus oozed from Rine’s nostrils. The drip and headache lasted for days.

For nearly six years, he was told by other firefighters that it was OK to wear nothing but a T-shirt when tearing into the guts of a smoldering house. It didn’t matter whether he wore an air mask. Like the other guys, Rine often put off showering, opting instead for a drink after his shift ended. He carried home his scorched helmet and blackened coat, trophies of a hero firefighter.

Then in September 2012, Rine learned that he had terminal stage 4 melanoma — skin cancer that had spread to other organs. He was given about a 5 percent chance of surviving five years.

Doctors also told Rine that his cancer likely was caused by his job, that the cancerous spots covering his body and a tumor in his lower back were a result of exposure to the carcinogens, flame retardants and toxic chemicals contained in uncounted burning objects inside homes, other buildings and vehicles.

Now, at 36, Rine is using the strength he has left to try and save thousands of other firefighters in the United States from his fate. He has traveled the state and country preaching to his firefighting comrades that they must protect themselves and one another from the cancer threat.

The threat affects people far beyond the firefighting community. Unsafe practices in firefighting are stealing our community heroes from us and creating a liability for taxpayers.

Rine pursues this calling to give them the warning he never got.

The fact that he’s dying won’t stop him.

The real threat

Firefighters are at least 14 percent more likely to develop cancer than the general public. They’re twice as likely to get skin and testicular cancer, and mesothelioma — a cancer that grows in the lining of the lungs, abdomen or heart that is caused by asbestos, according to a 2015 study by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

Most of the nation’s estimated 1.1 million firefighters didn’t know that when they entered the academy. Many still don’t.

“

Occupational cancer is something we need to look at and we need a paradigm shift. Cancer is a silent killer, and it is giving us a knockout punch.

Frank Szabo | Cleveland Battalion Chief

No one tracks exactly how many firefighters have been diagnosed with or have died from occupational cancer. But a Dispatch examination found that it’s a grave threat affecting fire stations in Columbus and around the nation.

In Columbus, at least 100 of about 1,500 firefighters currently are battling cancer. There likely are more: Some firefighters are never screened, hide their diagnosis or don’t seek treatment. And in Orange Township in Delaware County, an internal survey found that five of the township’s 41 firefighters have cancer.

Concord, North Carolina, fire officials were stunned when three out of a class of 10 rookie firefighters were diagnosed with cancer within two years on the job.

More than 60 percent of the names added to the International Association of Fire Fighters national memorial in Colorado Springs, Colorado, are firefighters who died of occupational cancer in the past 15 years. That’s a total of 1,155 cancer deaths just within the union’s membership. And that number is low because the deaths are self-reported from the local unions in 36 states that have presumptive cancer laws for firefighters.

The NIOSH study released in 2015 determined that the 30,000 firefighters in Chicago, Philadelphia and San Francisco were more likely to get cancer than the general public. Those firefighters had higher rates of skin, colon and prostate cancer and were twice as likely to be diagnosed with testicular cancer and mesothelioma.

To better understand the depth of the issue and whether firefighters take steps to prevent cancer, The Dispatch conducted two statewide surveys among nearly 1,300 active Ohio firefighters and 360 fire chiefs and found that:

Roughly one in six has been diagnosed with cancer.

About 85 percent know at least one firefighter who has been diagnosed with cancer; nearly 60 percent know at least one firefighter who has died from it.

About half of firefighters believe cancer is their greatest occupational risk. Ten years ago, only about 5 percent believed that.

Though 95 percent of chiefs surveyed said they know cancer is the greatest occupational risk to firefighters, only about half of their departments provide cancer-prevention training or implemented procedures to reduce the threat. Almost 30 percent of the firehouses don’t even have showers.

Here's how The Dispatch surveyed firefighters

See how fire chiefs responded to the survey

See how firefighters responded to the survey

Chiefs and fire-protection organizations that set policy have been resistant to new cancer-prevention policies because they have an outdated macho culture and some chiefs don’t have enough firefighters to give them an hour or more to decontaminate.

Want to participate in the conversation? Check out what's being said.

“We have an epidemic,” said Peter Berger, a fire captain in Hallandale Beach, Florida, who, like Mark Rine, has cancer is trying to warn firefighters everywhere about the risks. “It’s time to be honest with one another and ourselves, because we all want to go home to our families and retire instead of dying like this.”

‘It’s going to be OK’

Mark Rine was good at saving people.

And then Heather Durbin saved him from himself.

The couple were high school sweethearts, reunited years later, who fell in love.

Back then, Rine treated most people in his life badly and used them for whatever he needed. He drank too much. He became so depressed at times that he would sit in his truck and consider ramming it into something so his pain would end for good.

He isn’t sure why he acted that way.

In 2012, hours after a surprise family engagement party, Durbin was awakened in the middle of the night by a noise not far from her bed. Rine had mistaken the dresser for a toilet.

Rum always had been Rine’s drink of choice. He guzzled it almost daily, usually alone. He successfully hid his problem from Durbin for a while, and she tolerated his behavior.

But this was her breaking point.

“I can’t marry you if you are going to act like this,” Durbin shouted when he awoke the next morning, remembering nothing. “I can’t have someone drinking around our kids.”

Rine didn’t really remember the drunken night, but his fiancée’s message sobered him instantly. He walked downstairs, grabbed the remaining bottles of rum and poured the booze down the drain. He hasn’t had a drink since.

Shortly before they married, Durbin spotted a mole on the right side of Rine’s back.

She hounded him almost daily to have it checked. But he ignored her pleas until a mom from their daughter’s softball team noticed it and said her brother had one similar — and had recently died because of it.

So Rine made a doctor’s appointment.

Just two months after their summer 2012 wedding, a doctor told them that Rine had cancer and didn’t have long to live. He’s beating the odds, yes, but death is always in the room.

It’s going to be OK, Rine tells folks.

But he knows it really won’t be OK ever again.

Changing a ‘macho’ culture

When Columbus Fire Chief Greg Paxton retired in 2015, he planned to start a business and travel the world with his fiancée, Paula Friedrich, guided by a list of the best places for wine.

For nearly two years, they did just that. Then five months ago, he started urinating blood. Doctors discovered a cancerous tumor in his bladder.

Paxton had heard Rine’s warning lecture. But as chief, he had so many other things to worry about.

He also carried a level of arrogant invincibility. After all, this is a guy who once jumped into the frigid Scioto River in nothing but his long johns to save a drowning man.

It’s difficult for many people to acknowledge vulnerability. For firefighters, it’s nearly impossible.

But there are also the twin problems of awareness and enforcement. The Dispatch survey found that 90 percent of fire chiefs believed that their firefighters knew of the threats of chemical exposure, but a third of firefighters said they didn’t.

Fewer than half of rural departments in Ohio offer training or have implemented policies to prevent cancer, according to the survey of fire chiefs. Those numbers were better in suburban and urban departments, although a third of them also have not implemented cancer-prevention policies.

Departments rarely punish firefighters who don’t follow cancer-prevention policies, such as wearing their masks while on a fire scene.

Fire officials, chiefs and union leaders say they have made progress in the past decade in alerting firefighters about the cancer threat and implementing measures to protect them. All admit that it’s an arduous process.

“

We’re all macho bastards, and I mean that lovingly. We just don’t think of our safety first. That’s how we’re wired.

Brian McCafferty | firefighter & cancer survivor

The National Fire Protection Association is a nationwide group established in 1896 that sets policies and best practices for fire departments. Nearly all departments, including Columbus and Cleveland, say that meeting the agency’s policies is a priority in their mission statements.

Cancer and cancer-prevention measures previously never were mentioned in the group’s policies and best practices. The group this summer released an update to its safety practices that firefighters must follow.

For the first time, the NFPA officially acknowledged the cancer threat at its annual conference in Boston this year, holding its first-ever seminar on firefighter cancer.

Paxton, 64, acknowledges that it has taken too long to corral cancer in the fire service. The doctors removed his cancerous tumor three months ago but told him there’s a 75 percent chance that the cancer will return.

“My doctor asked me if I smoked, because this cancer is caused by smoking,” Paxton said. “I said, 'never smoked in my life.’ And then I told him I was a firefighter, and that’s when he said he has several firefighters who are patients.”

‘I hate this’

Rine is packing taco salad, grilled chicken and rice, and guacamole with pita chips in a one-man lunch assembly line when he stops to swallow three orange and white chemotherapy pills.

The dreadful side effects arrive in a few hours and take control of his weary body — a nauseous feeling he will fight off with gum. Then will come another restless night, followed by a hangover sensation in the morning.

Privately, he battles anxiety and daily thoughts of dying. The idea of leaving his wife without a husband and his five children — two his, two hers, one theirs — without a father is more haunting than death itself.

“I hate this,” Rine says.

But there is no time for self-pity. He kneels alongside 6-year-old Halle’s pink bed and reads their nightly Bible story in their Granville home.

He reminds 12-year-old Cohen to finish his science homework and critiques 14-year-old Blake’s throwing motion from a video of a junior-high football game last fall. He rolls his eyes at the suggestion that his 14-year-old daughter, Shelby, will be dating soon. (Rine’s oldest son, Jacob, is 18 and doesn’t live full time with them.)

Rine has mastered hiding his feelings. The constant exhaustion and the pain in his left leg are cloaked by sarcasm and blunt humor. It’s expected by all who know him, but his biting wit can rub strangers the wrong way.

He doesn’t second guess God’s plan.

Instead, he rises before dawn, feeling miserable, and sits in silence. He reads his Bible and prays before the children are awake.

“I tell people God did not give me cancer,” he says. “But he allowed me to have it because he knew what he was going to have me do with it.”

Rine could have quit in 2014, when his body no longer could handle 24-hour shifts of medic and fire runs. The money from a disability retirement might have been enough to keep him comfortable.

Or his bosses could have cut him loose.

Instead, his supervisors kept him on the city’s payroll as a firefighter and gave him a special assignment. His mission was to save as many firefighters as possible before he dies. He’s a traveling anti-cancer evangelist.

It started with a Google search that led to months of research on the cancer risk for firefighters.

He developed a 90-minute presentation to educate firefighters about the dangers of cancer and ways they can better protect themselves. His union president put Rine in a position to help his fellow firefighters not just in Columbus but across Ohio and beyond.

He has given hundreds of presentations in the past three years. He warns. He scolds. He preaches. He pleads. And sometimes, he yells.

He forces firefighters to look at their skin — to look at their spouses and their children, the people waiting for them at home.

The cancer risk, he vividly and desperately shows them, is real.

Subscribe nowLike what you're reading?

Stories that inspire. Coverage that informs. Investigations that affect change. This is real news just when it's needed most. This is The Columbus Dispatch. Subscribe today.

Stories that inspire. Coverage that informs. Investigations that affect change. This is real news just when it's needed most. This is The Columbus Dispatch. Subscribe today.

Chapter 2

The blade scrapes across Mark Rine’s bare back, grating his cancerous skin like cheese and adding to the maze of scars and spots.

A small hole in his flesh quickly fills with blood. But if Rine feels pain, it's hidden behind his smirk. He and the doctor exchange recipes during the 10-minute procedure, and the physician scolds Rine for considering more tattoos, something that could mask more cancerous spots.

Then Rine glances toward the corner of the dermatologist's office.

His son Blake is sobbing. He's waiting for his own skin to be checked and worrying that his dad will die soon.

Rine is used to running into burning buildings. Blake, a high-school freshman quarterback, is sometimes blindsided by blitzing linebackers. But there is no manual or playbook for handling these moments.

Rine's children are checked twice a year to guard against his biggest fear: that he has exposed his own family to the same poison that will end up killing him.

“I don’t like it here, Dad,” Blake said, trembling while holding on to his dad’s arm. “I just want to go home.”

Rine kneels awkwardly in a blue hospital gown. He’s almost helpless to comfort his son.

“Blake, look at me. Look at me, son,” Rine says. “Everything is going to be OK. We are going to get through this.”

Rine doesn't know which of the 200 fires he responded to since he began his career with the Columbus Fire Division in December 2006 caused his terminal cancer.

It could have been the blaze at a large airport storage unit where, for seven hours, he fought the fire around exploding propane tanks and boxes of bathroom cleaning supplies.

Or was it when he smashed holes through a three-story apartment complex roof at the biggest fire of his career, again without wearing a mask to protect against inhaling dangerous chemicals?

After both of those fires, he crawled back into his bunk at the station house and went to sleep without showering.

Maybe it was the dozens of dumpster and car fires he put out.

Or perhaps it was all of that.

The American Cancer Society says that multiple or repeated chemical exposures, whether big or small, can cause cancer.

“It’s impossible for a firefighter to know exactly what exposure was the one,” Rine said while chugging water to help combat the side effects of chemotherapy. “We don’t have those answers. But we do know what’s inside all those materials that were burning.”

Battling the heat

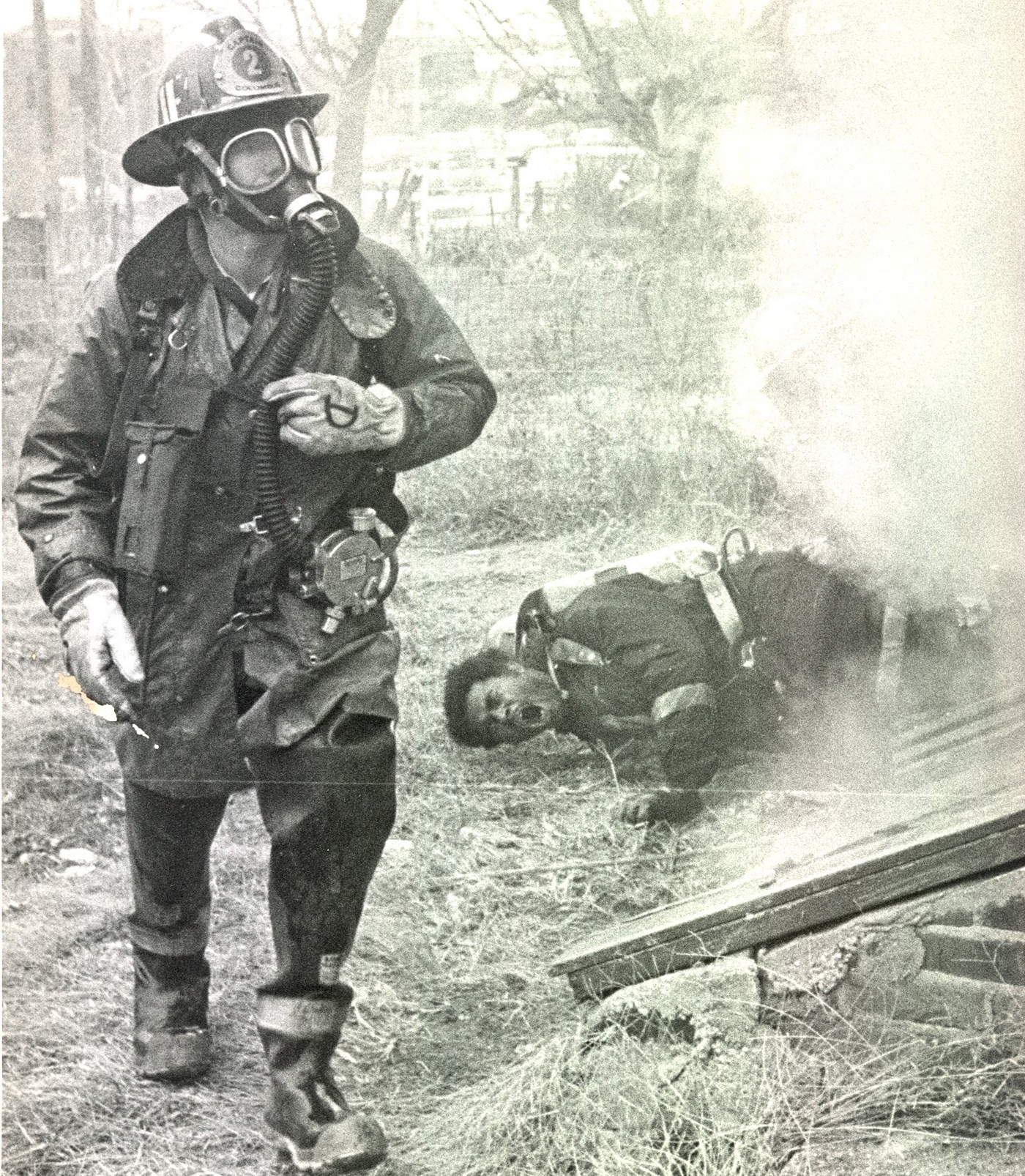

Firefighters are their own worst enemy when they don’t wear their gear, not only while fighting a fire but also when they go back into a smoldering structure to check for hidden flames or to gut the place.

Often, that work takes longer than the time spent dousing fires, which means longer exposures to toxins while unmasked.

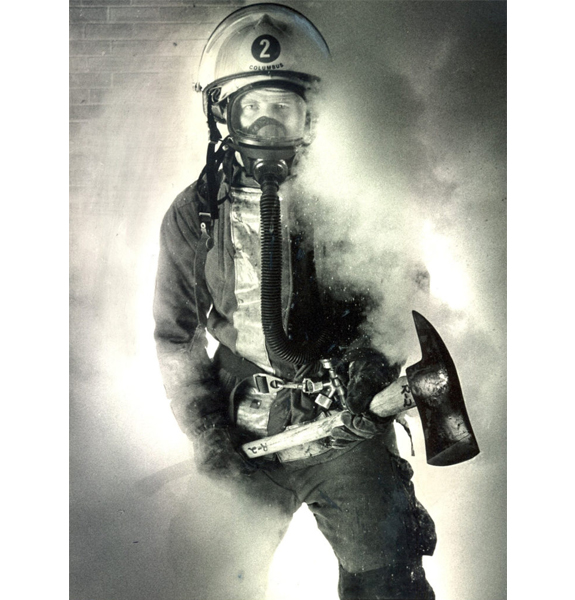

They typically wear nearly 70 pounds of gear, including bulky pants, a thick coat, insulated boots, protective gloves, a bulky fabric hood and a rubber mask that’s part of a self-contained breathing apparatus with an air tank.

The main reason some don’t wear their gear at all times is obvious: It’s hot and uncomfortable.

A firefighter’s body temperature can rise to 105 degrees when in action. Each often lugs heavy hoses, axes and cutting equipment that can add even more weight.

Some don’t wear their gear because they never heard about the cancer threat. Some don’t wear it because they either don’t care or don't believe the threat is real.

And walking around in a smoldering, hot building with just a helmet and T-shirt is something firefighters have done for decades. It’s human nature to want to rip off that heavy equipment and breathe without an air tank as soon as the fire is extinguished.

“It can feel suffocating at times,” said Joel Rampe, a Findlay firefighter for the past 15 years. “I’m not making excuses for any of us, because the gear should stay on. But once the fire is out, you can still be at the scene for hours and hours, and you are exhausted.”

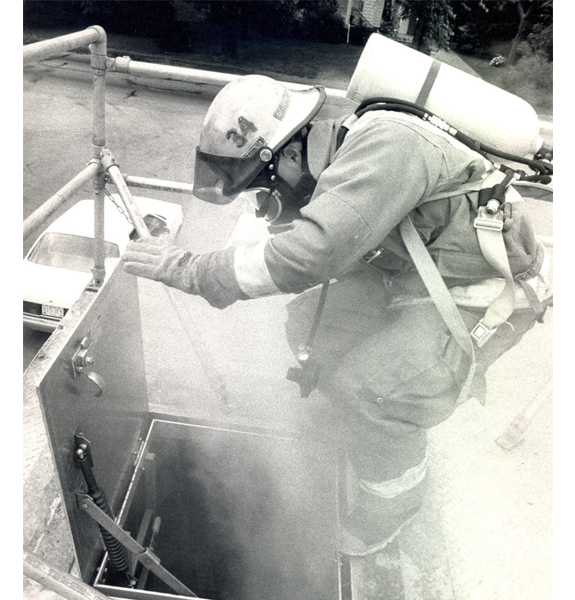

But the work they call the "overhaul" — when firefighters are opening walls, ceilings and partitions to check for fire lurking within them — is the most dangerous for contact with carcinogens. The smoldering ruins typically are at their most toxic levels then. Without a mask, firefighters inhale the gases.

The suit itself also absorbs toxins, which is why it’s vital for firefighters to clean their gear rather than throw it in the back of a truck or take it home where it can potentially affect their families.

Want to participate in the conversation? Check out what's being said.

Keeping the full gear on doesn’t eliminate the possibility of firefighters being exposed to the chemicals and toxins that can cause cancer. Small gaps between the hood, coat, pants, gloves and boots can allow smoke to snake up under the clothing and settle on skin.

And the more a firefighter’s body temperature rises, the greater the risk the toxins can be absorbed into the skin. With every 5 degrees that body temperature rises, skin absorption rates increase by as much as 400 percent, according to the Firefighter Cancer Support Network, a nonprofit based in Burbank, California.

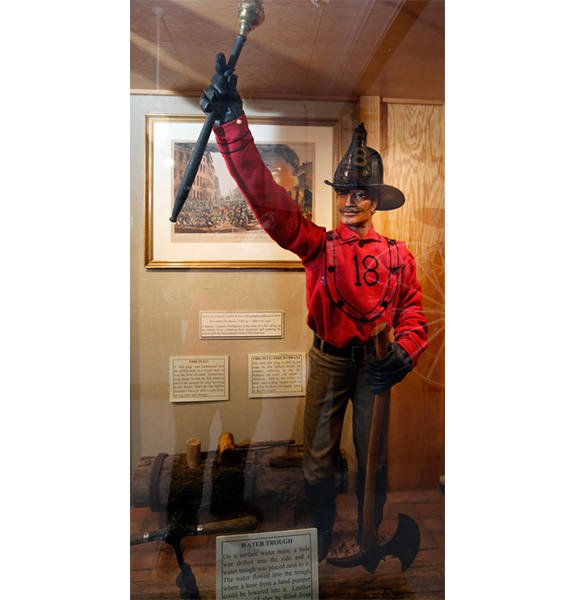

Gear through the years

Toxins at home

Dayton firefighter Jim Burneka Jr. went through every piece of clothing people gave him and his wife for baby-shower gifts.

His wife gasped as he loaded brand new sleepers and onesies into a trash bag and tossed them out. The clothes had flame-retardant chemicals in them.

“They’re too dangerous, and they don’t do anything but cause cancer,” he said. “No one should be using these.”

Flame retardants can be a major threat to firefighters because when they burn, carcinogens are released into the air.

The chemical-based retardants are in many household and office items. They can be found in infant clothes, high chairs, mattresses, pillows and even Barbie dolls.

They are supposed to give the public and firefighters more time to escape a fire by smoldering before flames erupt. But study after study from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and several universities have raised questions about their effectiveness.

The flame retardants don't have to ignite to be harmful. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that 97 percent of Americans had traces of flame-retardant chemicals in their blood.

The big shift to flame retardants came in the late 1970s and is traced directly to big tobacco.

At that time, there was concern among firefighters and state fire marshals about the number of people falling asleep with lit cigarettes. Lawmakers across the country began pressuring tobacco companies to produce a cigarette that would extinguish after a short period if it was not being smoked.

Tobacco companies were forced to release 13 million documents in 2011 as part of a federal lawsuit settlement involving the tobacco companies' lack of warning to the public about the hazards of smoking. Those documents show that in the 1980s and into the 1990s, tobacco companies balked at making a fire-safe cigarette for fear it would reduce the product quality.

Instead, they planned to put flame-retardant chemicals into things found inside the home.

The records show the industry spent millions and offered grants to fire organizations to get buy-in for the plan. They hired lobbyists to persuade fire officials that this was the path to better fire safety.

The linchpin in the whole plan was to gain support from the National Association of State Fire Marshals and ply the group with grant money. The marshals even put a tobacco lobbyist on their governing board, according to court records.

Tom Brace, one of the founding members of the Fire Marshals Association and once fire marshal for the states of Minnesota and Washington, said the group was unaware of tobacco’s influence on flame retardants.

Brace said the group would have done things differently if that had been fully known at the time.

“Cancer wasn’t talked about at the time, either, not that I recall,” Brace said. “Since then, we’ve learned a lot more about flame retardants, and some of the bad ones have been eliminated.”

And though Burneka's wife and friends might have questioned him throwing out baby products, it appears he was ahead of the curve.

In late September, the Consumer Product Safety Commission voted to warn the public about dangerous chemicals in baby and toddler products, mattresses, upholstered furniture and electronics enclosures. The federal group for the first time said it plans to discuss banning a whole class of flame retardants that have been found to be harmful.

'I can't do this anymore'

Mark Rine kneels down in the street, almost gasping for air. He can’t muster the energy to remove his air tank.

He has been fighting a small fire on the second floor of a quadruplex not far from his firefighting home at Station 8 on the city's Near East Side for just 20 minutes.

In the academy, Rine would always beat the other guys during training races when they had to run carrying the bulky 50-foot hose. He mocked them by singing songs while he ran.

Now, his body is betraying him.

After pulling a man to safety, Rine’s friend crouches down in front of him.

“Hey man, are you OK?,” he asks. “Mark, are you going to be OK?”

It is summer of 2014, about two years into Rine's fight with melanoma. He has been growing weaker every day but doesn’t want to admit it. The chemo injections have brought with them insomnia, vomiting, night sweats and constant exhaustion.

Forty pounds have dropped off his once-powerful 225-pound frame in a year.

He knows that the other guys at Station 8 see what is happening to him. They see Rine giving himself chemo shots. Rine worries that they might think he can’t carry his weight anymore.

They’ve never said a word, and neither has Rine.

Rine sits on the fire truck as it turns the corner. He looks back at the last structure he would ever run into as a firefighter.

“I can’t do this anymore,” he says softly.

Rine is close to finishing out his last 24-hour shift when he meets up with Shawn McConnell, one of his closest firefighting brothers, in the station-house bay.

The two tough guys sit in the back of an ambulance together one last time and fight back tears.

Rine tells McConnell he has to quit.

“I just can’t do it anymore,” Rine says. “I can’t be a real firefighter anymore."

“It’s going to be OK man,” says McConnell, embracing his buddy.

Soon, Rine begins peppering McConnell with daily calls and texts of stories and statistics about how firefighters all over the world are dealing with the cancer threat. Not enough is being done, he says, to warn fellow firefighters about the dangerous chemicals and flame retardants in burning materials that they immerse themselves in.

McConnell tells Rine that he has an even bigger calling. He needs to share this message.

“You are going to save more lives doing this than before,” McConnell said.

Adding more chemicals

Columbus Fire Chief Kevin O’Connor has no doubt that flame retardants have, at times, prevented fires and saved his firefighters from a brutal fire.

“Not having fires has saved my guys from exposures for sure,” O’Connor said. “The problem is, there is not enough research out there, and when you add more chemicals such as flame retardants, it’s just more chemical we are being exposed to.”

Heather M. Stapleton is a chemist and associate professor at Duke University whose work focuses on environmental risks from chemicals such as flame retardants.

Some of her research, which was funded by the National Institutes of Health, found that manufacturers' tests showing that flame retardants increase escape time for firefighters were misleading. The furniture in those tests, Stapleton said, was saturated with more flame-retardant chemical than what is actually sold to consumers.

“There is not good data out there suggesting they are providing a true benefit,” Stapleton said.

Stapleton's research is clear, however: Chemicals in flame retardants are linked to cancer.

In 2013, California lawmakers changed rules for flame retardants, saying they had to be able to smolder if exposed to a small open flame for a short period of time. This allowed manufacturers to line furniture with a fire-prevention shield material instead of soaking the foam cushions with flame retardants.

The law is aimed at eliminating the most harmful flame retardants. But it will take years to phase the bad stuff out of homes and offices across the country, including Ohio.

Ohio's law on flame retardants largely mirrors national standards set by the National Fire Protection Association, which vary depending on fabric material but allow numerous chemicals to be used to keep flames at bay.

The city of Boston was able to amend its fire code in 2013, allowing hospitals, schools and campuses with sprinkler systems to use furniture free of toxic flame retardants.

And despite tobacco companies' efforts to keep lawmakers from tampering with their product, every state has passed laws requiring fire-safe cigarettes since 2011.

'This is home'

Firefighters at Station 8 have invited their brother for lunch, but Mark Rine is dreading the reunion.

It’s been almost two years since he last stepped foot inside his second home.

Rine misses his brothers and sisters more than he can express. He isn’t whole without them.

He is starved for the camaraderie of the station house, the smell of the chow and being on the front lines when an alarm goes off.

He had wanted to be a firefighter since he was a kid.

Rine remembers laying out his dress blue uniform after he graduated from the academy — the stitching, the six gold buttons on the double-breasted jacket.

His chiefs and fellow firefighters considered him one of the best paramedics in the city. He was what he calls a “real firefighter” for eight years until cancer took it all away.

Now, Rine spends most of his days alone in a dark office at the iconic Station 67 in Franklinton, working directly for the fire union president. He helps the city’s active and retired firefighters with medical benefits, pension questions, cancer claims and anything else they might need.

“Time to get this over with,” Rine says as he climbs into his 2013 Suburban.

The guys are waiting for him in front of the old station house, and the angst on Rine's face disappears. Instantly, he receives a heavy dose of what he has been craving.

They jab and swear, and Rine, who never cusses, can’t stop laughing.

“We have missed you man,” says Lt. Steve Kerns as he embraces one of his closest friends. “This place hasn’t been the same without you.”

They gather around the indoor picnic-style tables to devour taco salad made by a firefighter Rine calls Papa.

Rine starts giving the youngest guy at the station grief for not cleaning the kitchen as spotlessly as he once did. Station 8 might be a gritty, old-school firehouse, but it has a proud reputation as the cleanest in the city.

The old, funny stories about Rine consume the reunion early on.

There was one when they needed to bandage only a man’s mouth but took him into the emergency room wrapped like a mummy.

And there were hundreds of runs to the apartment of a crack addict who Rine helped so many times, he considered her family.

No one says the word “cancer.” But eventually, someone asks Rine his least favorite question.

“How you feeling, man?"

The jokes abruptly stop. The station goes silent as Rine talks about his chemo treatments, the moles sliced from his body and how he tries to keep it all away from his family.

His mood darkens when he starts walking around the station. He can barely look at his old locker.

When he limps into the bunkroom, he grimaces and sighs.

There are eight bunks in a room that looks like military barracks. Rine’s bunk is the third one in on the left. He goes one by one and names off the buddies who slept in each bunk.

“This is home,” he says. “This is where I spent a third of my life. I hate this. I was part of something here, and it became part of me. And it was taken from me. It’s why I do the talks, so other guys don’t have to feel this, or worse, taken from them.”

An alarm rings and echoes through the station house.

Rine watches the ambulance pull away, puts his head down and quietly walks out the door.

Subscribe nowLike what you're reading?

Stories that inspire. Coverage that informs. Investigations that affect change. This is real news just when it's needed most. This is The Columbus Dispatch. Subscribe today.

Stories that inspire. Coverage that informs. Investigations that affect change. This is real news just when it's needed most. This is The Columbus Dispatch. Subscribe today.

Chapter 3

Mark Rine points to the family photo of his five young children and beautiful wife projected on the wide screen above the stage. Then he tells the crowd of Newark firefighters that terminal cancer likely will kill him soon.

He tells them he won’t be there to walk his daughters down the aisle.

He won’t be there to help his sons fix their cars.

“Let me be the one who dies for you,” Mark Rine exclaims, throwing his hands into the air. “I can’t go back and do the right things to protect myself. All I can do is convince you to do the right things so you don’t lose everything and your family doesn’t suffer.”

Rine thunders away at his latest audience of firefighters for longer than the usual 90 minutes.

He implores them to wear all of their gear until they are done working at a fire scene, then to shower immediately afterward before they get near their families or anyone else.

He rattles off statistics of how firefighters are far more susceptible to some cancers than the general public.

He tells them that nearly every burning home is filled with products containing chemicals that can cause cancer if the lungs or skin are exposed to them. And he tells them: If you haven’t been screened for cancer yet, you'd better make an appointment.

Some firefighters, even the older guys known as "old heads," roll up their shirt sleeves or raise their pants legs to check their skin for spots. Others scribble notes, nod their heads or whisper to one another that this presentation is scarier than running into a burning building.

He shows them one more photo of a firefighter wearing only a T-shirt while thrusting an ax into a roof. Billowing smoke engulfs his exposed face.

“When you guys walk out of that door, it’s on you to not be that guy in the picture,” Rine says. “It’s hard and hot and uncomfortable to wear your gear the whole time. I know. But go home and tell your family they are not worth wearing your equipment the whole time. If you want, I’ll trade you spots in life.”

Rine receives a standing ovation. But as always, he knows that some of the guys won’t buy the whole cancer thing.

One old head Rine met in another small town hadn't cleaned his blackened helmet for 19 years and had about a dozen suspicious spots on his forehead. And a veteran firefighter in Cleveland openly heckled Rine while he was on stage and told him the cancer stuff was “bullshit.”

“Some will get it; some won’t,” Rine said, shaking his head. “Sometimes, it feels like I’m wasting whatever time I have left.”

He guesses that about half of the firefighters he has encountered will make real changes.

But even in Rine’s own department, there is no formal operating procedure to protect firefighters from cancer. There is no mandate to take a shower or clean their gear and equipment at the scene

Columbus Fire Chief Kevin O’Connor said there are unwritten rules that his firefighters follow when cleaning themselves after a fire. O’Connor said he constantly monitors best practices and implements cancer-prevention measures within his operating budget.

“There’s no national best practice on some of these things,” O’Connor said. “So we try to make changes where we can based on what we know works.”

Until recently, the National Fire Protection Association, which sets standards for departments such as Columbus, had no guidelines on cancer prevention. The agency released standards aimed at cancer prevention for the first time this summer. They do not mention the word cancer specifically, but they lay out increased training and education on chemical exposures and how to decontaminate after an exposure.

Want to participate in the conversation? Check out what's being said.

Another significant new standard mandates that firefighters across the country wear their breathing apparatus and air tank during the "overhaul" work after a fire is extinguished. This involves tearing open walls and ceilings looking for hidden flames.

Money is another obstacle to better cancer prevention for firefighters.

Many departments operate on flat or reduced budgets that have kept manpower at the same level as in the 1990s.

Columbus has about 1,560 firefighters and paramedics, the same number the city had in the late 1990s despite a population boom of nearly 200,000 new residents in the last 20 years.

Cleveland's fire budget was reduced by $2 million to about $86 million from 2015 to 2016, according to city budget documents. Cincinnati had to rely on about $8.5 million in one-time federal grants to fund its recruit classes for the past two years to maintain its ranks of 850. And budgets are far worse for volunteer fire departments that have less support than professional units.

Burying too many

Frank Szabo can see the bodies of firefighter brothers in their coffins as he says their names.

“Tommy Hough, Larry Huffman, T-Bone Terry Bradesca.”

Firefighters call one another "brothers." And in his 25 years as a firefighter, Szabo has helped bury too many.

The Cleveland Division of Fire, which has about 750 firefighters, doesn’t track how many have cancer.

Szabo’s roles as a battalion chief for Cleveland, and as pension and benefits coordinator for the union, have put him on the front lines. It’s his job to protect firefighters on a fire scene and, if necessary, help them when they’re dying of cancer.

He’s fighting an uphill battle against a few million dollars in budget cuts in recent years and an eroded relationship between the union and the fire administration. The division promotes cancer awareness with signs in fire stations and periodic announcements from the chief’s office.

“We don’t get the chance much to talk about cancer and what to do about it,” said union President Tim Corcoran.

Unlike similar large urban departments in Columbus and Cincinnati — and shunning national standards set by the National Fire Protection Association — Cleveland doesn’t have firefighters fitted for their own masks that connect to the air tanks.

Instead, the firefighters share breathing masks, cleaning them and passing them from one shift to the next.

Each firefighter depends on the firefighter before him or her to inspect the mask.

If firefighters want their own face piece, they must pay $400 out of their own pocket.

And it’s common in many departments that once air tanks are emptied, firefighters simply remove their masks and keep working rather than fetching new tanks.

“Guys don’t want to be seen leaving a structure while their buddies are still inside working and busting their ass,” said Cleveland fire Lt. Sam DeVito. “It’s something in our culture that has to change.”

Earlier this year, Cleveland Fire Chief Angelo Calvillo verbally altered a decontamination plan that allowed firefighters to be out of service for 30 minutes after fighting a fire so they could change and shower. Instead, he ordered firefighters to remain in service to better serve the public and not tax crews in other areas of the city.

Union officials filed a grievance, and both sides are still trying to work out a solution.

Calvillo did not return calls seeking comment.

'I'm just a guy with cancer'

Mark Rine looks out at all the fresh-faced recruits and forgets about the throbbing pain in his leg or that he hasn’t been able to move his bowels in almost a week.

This place, the Ohio Fire Academy on East Main Street in Reynoldsburg, is Rine's favorite setting to deliver his cancer-prevention speech.

This is where he can find untainted minds, the young recruits who haven’t developed bad habits. This is the next generation of firefighters who can help him change the culture.

Rine loves when the spouses come, too. They point to their loved ones as he talks and reinforce his point that they must protect themselves.

Rine’s energy — today, it’s high — captivates recruits who might have thought that fire or cardiac arrest were their biggest threats.

Rine looks like a football coach stalking the sidelines, striding back and forth in front of the room. He can’t stand still. His leg is hurting more than usual today.

The movement helps lessen the pain.

“You guys are the era of change,” Rine says. “I want to teach the pups before the old dogs teach you their bad tricks.”

After his talk, Rine tries to rush out of the room before the recruits can get to him. He doesn't like to be the center of attention.

He’s not fast enough. The recruits approach him one by one. One thanks him for trying to save their lives. Another tells him his dad was a firefighter who died of cancer. A third promises he will always wear his full gear and clean it after every fire.

“I’m no hero,” Rine says to one. “I’m just a guy with cancer.”

Two weeks later, Rine is back at the academy, but his mood and audience are much different.

This time, he has a chance to persuade about 50 fire chiefs from big metro departments and small township firehouses that they must do more to protect their firefighters.

He is terse, even angry.

“If you don’t get something out of this, that means you either don’t care or you slept through this,” Rine says.

He tells them what it was like explaining terminal cancer to his sons, how the paramedic partner he worked with in Columbus had to rush him to the hospital while he was on duty and what it's like undergoing cancer treatment.

Then he goes hard at the chiefs in the room.

“We talk about family, and when something happens in another department, we are the first ones to extend a hand to help, to hold fundraisers and dinners,” he says. “But you also have a duty to protect your guys — to send them home every day safe to their families. That’s your job. You must do it. It starts and stops with you.”

Higher expectations

Awareness of the cancer threat is increasing. According to a 2017 Dispatch survey of Ohio firefighters, 50 percent are concerned that cancer could lead to their deaths. Ten years ago, only 5 percent considered cancer a threat.

Still, 37 percent do not shower within 60 minutes of leaving a fire scene. And about 50 percent said they have only one set of gear to wear to a fire. Firefighters across the state said that a second set of gear would help prevent cancer because they wouldn't be wearing dirty gear.

On a gloomy February day, the Newark Fire Department welcomed five new members at a graduation ceremony inside its downtown station. It was the largest graduating class in decades for the Licking County city of about 49,000.

The recruits take an oath to protect the public and the person next to them, to honor the tradition, serve unselfishly and with courage no matter the circumstance. But despite this pledge, not one firefighter has talked to these rookies about one of the greatest threats they will face from the job.

Newark doesn’t provide a second hood for firefighters to wear under their helmets. The hoods protect the neck and jawline, but they also soak up cancer-causing particles. Members of the National Fire Protection Association's safety committee say that swapping those hoods out immediately for clean ones after extinguishing a fire can dramatically reduce cancer risks.

The city has done some things to help prevent cancer in firefighters, such as adding wipes to firetrucks and issuing directives for firefighters to clean themselves after a fire. Equipment is stored safely inside fire stations to try and prevent contamination.

Firefighter Jarrad Tracy watched the graduation ceremony from the back of the room.

Tracy, a central Ohio native, is one of three firefighters from a 2006 rookie class of 10 in Concord, North Carolina, who was diagnosed with cancer. Doctors found a football-sized tumor in 2007 in his chest after Tracy passed out during a training exercise. Tracy went through treatment for a year. He returned to Ohio in 2012 and was soon hired by the Newark Fire Department.

His best buddy in Concord, Matt Sellers, was diagnosed with a rare, deadly form of T-cell lymphoma. The cancer is found in 1 percent of all cancer diagnoses and attacks the fatty layer of the abdomen. Sellers battled through two years of intense treatment, a brutal bone-marrow transplant and numerous doctors telling him he’d never fight fires again. Last fall, his doctor cleared him to return to work.

Concord has since implemented some of the most proactive cancer-prevention measures in the country. The 250 firefighters there are now required to wipe down before they leave the scene. They must shower after every fire. The firefighters change into coveralls at the scene. Their turnout gear is immediately bagged up on the scene and transported for decontamination.

After the Newark ceremony, Tracy went to the fire chief.

“Can I talk to them?” he asked.

Tracy gathered those five rookies at the kitchen table inside the fire station. He told them about his cancer. It’s in remission. He still fights fires. But he is much more careful, and he hopes they do the same.

“In Concord, I was up in the attic on a small kitchen fire and it was smoldering in the attic, and I’m shoveling stuff through a hole we cut and I’m a coughing, my nose is running and my eyes filled with stinging tears,” Tracy tells them. “All the while, I have an air pack on my back and a mask hooked to the air pack that’s not on my face.”

Would he do that today?

“No way.”

'Something is going to kill me'

It’s 39 degrees just after dawn one April morning, and Mark Rine is the only one walking into Ohio State University's Martha Morehouse Medical Plaza wearing shorts and flip-flops.

He always feels warm, like he has an eternal fever. And it's worse today, when Rine will learn whether the cancer inside him is getting worse.

He comes to these appointments alone. It’s the way he and his wife, Heather, want it. She was there for all of the surgeries and hospital stays, but she didn’t like seeing the other sick people and being reminded of what her husband faces.

She gets emotional, and for Rine, these appointments are all business. He needs to focus on the precise clinical details, an approach that has helped keep him alive for five years.

Rine is more nervous about this appointment than any in years. He hasn’t been feeling well for months. The pain in his leg is almost unbearable. He has trouble sleeping. He’s constipated. He’s depressed.

A nurse draws blood before sending him up to the fourth floor to see his oncologist, Dr. Kari Kendra.

He jokes with a nurse that he is the one with cancer but she is the one getting more gray hair. The jokes are a defense mechanism, helping him and others get through tough moments.

But there is no hiding from today.

Dr. Kendra tells him the cancer in his lungs has grown since his last appointment a few months ago. She also tells Rine there is no reason to panic.

Rine doesn’t, but Kendra’s second announcement is far more alarming. She is taking him off the chemo drug that has helped keep him alive for several years. There are concerns that the drug is no longer effective because his body has become immune to it.

The hope is that the side effects will lessen, but that is of no comfort to Rine, whose mind wanders to the fear of leaving behind a wife and their children.

“I trust you,” Rine says nervously to the doctor, who has helped him defy his odds.

He walks out of the hospital taking a cancer inventory in his body.

There are tumors in his spine. Those tumors cause constant throbbing pain in his left leg and occasional pain in his right leg. There are spots in his lungs. And there’s the potential for more cancerous spots on his skin. Each is potentially lethal.

“

Something is going to kill me; it’s just a matter of what and how long it will take. No reason to worry about what I can’t control.

Mark Rine | firefighter

Subscribe nowLike what you're reading?

Stories that inspire. Coverage that informs. Investigations that affect change. This is real news just when it's needed most. This is The Columbus Dispatch. Subscribe today.

Stories that inspire. Coverage that informs. Investigations that affect change. This is real news just when it's needed most. This is The Columbus Dispatch. Subscribe today.

Chapter 4

The tears drip onto the shoulders of his dress blue uniform.

There is no joke that Mark Rine can tell to deflect the attention from the admiring crowd gathered around him in the Station 8 truck bay. This is Day 2 of another chemo cycle, and he feels like hell.

He is being honored as the Columbus Firefighter of the Month. It’s a prestigious distinction among firefighters that a small percentage receive in their careers, and at 35, Rine might be the youngest firefighter in the city’s history to receive it.

But he doesn’t want it.

He doesn’t think he deserves it. He dislikes attention. And most of all, in his mind, he is no longer a "real" firefighter.

He stands with his wife, Heather, and four of their five children in front of the engine and ladder truck that he desperately wishes he could climb into again. The humid truck bay is filled with firefighters and paramedics who love Rine and served with him, chiefs he served under and other dignitaries from the city.

Rine was nominated by his old firefighting buddies at Station 8. And the nominating letter, penned by his good friend Lt. Steve Kerns, embarrasses Rine.

It talks about Rine being one of the best firefighters and paramedics that Columbus has had. It notes his tireless work to help pass the state’s new presumptive cancer law that would allow firefighters and their families to collect compensation if a firefighter is diagnosed with a work-related cancer. And it praises his life-saving cancer-prevention crusade.

“You are not getting this award because you have cancer,” said Columbus Fire Chief Kevin O’Connor. “I want everyone to hear that. You are getting it because you are a great firefighter, and you have put us before yourself.”

When it’s Rine's turn to speak, he pauses.

“This is all I ever wanted to do — just ride in one of these trucks,” he says. “I can think of 1,500 other guys who are more deserving.”

Rine's two sons put on his dad’s old fire hat at the end of the ceremony, and tears flow throughout the station.

Jack Reall, an assistant chief, follows O’Connor with more words that leave Mark and Heather Rines' 14-year-old daughter, Shelby, sobbing with pride.

“I knew when Mark was coming up through the academy that he was going to save as many lives in the service as anyone,” Reall said. “And he is.”

Suggest to Rine that he is a hero on a good day, and he will roll his eyes. Say it on a bad day, and you might get a tongue-lashing about how it's insulting to Jesus Christ to call him that.

But if you retrace his three-year journey across the state and beyond, you will find a trail of firefighters who credit him for saving their lives.

There is no way of knowing exactly how many firefighters practice what Rine preaches to them. But there is plenty of evidence for even Rine to acknowledge that he might have made a difference.

Some fire departments established cancer-prevention committees almost immediately after he spoke to them. Some chiefs displayed standard operating procedures on the station wall detailing how firefighters must clean themselves and their gear after a fire. Some firefighters finally went to cancer screenings and discovered cancer early enough to be treated. Some held pancake breakfasts or chicken barbecues to raise the money for more gear.

That was the case in the Orange Township Fire Department in Delaware County, where the day after Rine spoke to their 62 firefighters, Chief Matt Noble laid down a new law.

“Boys, you are going to do this for the protection of our crews,” he said. “Everyone makes it home safely, and everyone enjoys their retirement.”

The department also conducted an internal survey, said Lt. Scott Rice. It showed that five of the 41 firefighters who responded have been diagnosed with cancer.

Not even the chief knows who they are.

'He saved us in so many ways'

The volunteer firefighters sometimes would leave the family barbecues to go fight a fire and return to the picnics covered in soot and filth.

They wore melted, dirty helmets like badges of honor. They rarely cleaned their gear and never wiped themselves down at a fire scene. They couldn’t go back to the firehouse to shower because there wasn’t a shower.

At least a half-dozen of the 35 members of the Kalida Fire Department, about 110 miles northwest of Columbus, had been diagnosed with some form of cancer. And others with ominous spots on their skin never had been checked by a doctor.

They called Mark Rine for help. He arrived in the blue-collar town of 1,500 in the summer of 2015.

Most of the volunteer firefighters never had heard a word about cancer being tied to firefighting. They worried most about what they might have done to expose their families.

Want to participate in the conversation? Check out what's being said.

Two years later, at a massive blaze, the lifesaving changes were obvious to Chief Dale Schulte. All of his guys were wearing their full gear for seven hours, even during the hot, nasty process of gutting the house.

The firetrucks were stocked with moistened wipes they used to at the scene. His guys scolded firefighters from other departments for wearing shorts. Women brought them food, but no one would eat it until they were able to clean up back at the station.

And even then, when a little girl came running out of the station toward her dad, he refused to hug her until he could go somewhere to shower and change.

“Everyone bought into Mark’s message,” Schulte said. “He saved us in many ways.”

There is still more to be done in Kalida, in Putnam County, and the hundreds of other volunteer departments around Ohio.

It’s in these places that Rine’s help is needed the most. These are the factory workers, bankers, truck drivers and engineers who don’t have a union or even full-time fire chief focused on protecting them from cancer, let alone the newest fire trucks or latest equipment.

In Kalida, they still don’t have a shower. And there is no money in their annual $65,000 budget to install one. That project would cost a minimum of $50,000, because they would have to add onto the 50-year-old fire station.

Bob Unverferth, a volunteer firefighter in Kalida, has Rine to thank for catching his cancer.

Unverferth ignored the red spot on his right cheek that just wouldn’t go away. The week after Rine delivered his powerful speech in Kalida, Unverferth finally visited the doctor.

The spot was pre-cancerous, and the doctor told him he was lucky he hadn’t waited much longer.

“If Mark hadn’t come, I might not be alive,” said Unverferth, 67, who has been a volunteer firefighter for 32 years. “We have come a long way since Mark was here.”

Vital cancer screenings

Moles have dotted 38-year-old Cal Holloway’s skin since puberty, but he didn’t give them much thought while fighting fires in Dayton the past 16 years.

Then, in summer 2016, Mark Rine gave a presentation to the Dayton Fire Department and said that cancer was killing firefighters far more often than fire.

Holloway wasn’t present for the speech but he heard that Rine had arranged for a dermatologist to perform cancer screenings on any firefighter who wanted checked.

Why not, Holloway figured? He already was on duty that day.

A few weeks later, Holloway opened a letter explaining that a spot on his leg and one his left shoulder were cancerous. He had stage 2 melanoma.

“I had no symptoms,” he said.

Cancer screenings are not mandated for firefighters in Ohio, although many departments require annual physicals. But nearly all of the 1,300 firefighters in Ohio who responded to a statewide Dispatch survey said they would like their departments to require free screenings.

There is clear evidence that a simple screening from a dermatologist could save many firefighters from Mark Rine’s fate.

Holloway was one of five Dayton firefighters screened the day that Rine provided free screenings who were found to have skin cancer.

Dayton firefighter Jim Burneka Jr. doesn’t have cancer, but the rash of cancer diagnoses within his department compelled him to raise awareness.

With encouragement from his chief, he wrote a 50-page report on how the department was failing.

“I was blatantly honest about where we were on some things and what we needed to do,” he said.

Union leaders there pushed for Dayton's most recent contract to include a second set of gear at about $5,000 per set. That allows firefighters to use fresh gear while gear just used in firefighting is being cleaned of contaminants. That gear is still being phased in for all of Dayton's roughly 300 firefighters.

The city also implemented other safety measures.

Firefighters now must wear their breathing masks while cleaning out a structure after the fire is extinguished. A medic is now at every fire scene to treat firefighters. Every fire vehicle carries sunscreen. And equipment is stored differently inside the station to protect it from diesel exhaust.

Burneka is pushing for more changes. He wants a policy that firefighters must shower immediately after fires, among other things.

“I feel like my department is sincere about doing stuff, but they have to operate within their budget,” Burneka said. “But sometimes it’s not enough, and we have to apply for grants for things.”

Many of Dayton’s fire stations don’t have machines known as washer-extractors to clean the gear. The department has applied for grant money to get them installed.

They can’t come soon enough for firefighters such as Holloway.

A recent checkup revealed more cancer. Doctors resumed carving away pieces of him in September.

"We go into this job knowing the risks, but the risks of cancer weren't something we were educated on," Holloway said. "Having cancer is scary, but it's not scary enough for me to leave the fire service."

'God has a different plan'

The retired firefighters are packed inside the local VFW hall in Merion Village drinking cans of Budweiser and Miller Lite while lamenting their bad backs and creaky knees. They are sharing pictures of their grandchildren and telling some old fire stories that have grown in lore over the years.

Their booming voices are at a fever pitch until their union bosses call the monthly meeting to order and Mark Rine stands at the front of the room.

“Who the hell is this young guy?” whispers one of the retirees who are from different unions throughout central Ohio.

Rine tells them he is going to die soon. He has terminal cancer and it was caused by being a firefighter.

The only sound now is the humming of a vending machine motor.

Rine tells them that Ohio now has a law that allows firefighters to file for compensation for themselves or their families if they were diagnosed with cancer. He explains the fine print of the law while the older men start looking down at spots that cover their skin. Many of them wouldn't qualify for benefits or financial help under the new law, which exempts anyone older than 70.

There are more whispers.

“I’ve heard about this guy,” another retiree says to his buddy. “He is out there trying to save us.”

Rine answers all of their questions about cancer, prescription drugs and anything else.

He is soon surrounded by the retirees who are patting him on the back, grabbing his arms and telling him what a difference he is making. A couple use the "hero" word.

Rine walks out of the hall shaking his head and hears sirens in the distance.

“

I’d rather be on a ladder truck or making a medic run with those guys. That was who I am. But I guess God had a different plan.

Mark Rine | firefighter

Subscribe nowLike what you're reading?

Stories that inspire. Coverage that informs. Investigations that affect change. This is real news just when it's needed most. This is The Columbus Dispatch. Subscribe today.

Stories that inspire. Coverage that informs. Investigations that affect change. This is real news just when it's needed most. This is The Columbus Dispatch. Subscribe today.

Chapter 5

Mark Rine wants to wear his faith on his sleeve.

He tells Steve Holdren, owner of Thou Art in Lancaster, that he wants it all the way down his left arm: The spike being driven through the palm of Jesus Christ. Christ looking to the heavens wearing the crown of thorns. Rine's children’s names and birthdays, and his wedding anniversary in Roman numerals.

Then he tells the faith-based tattoo artist that he has terminal cancer.

Holdren’s eyes widen, but he doesn’t hesitate to ask Rine what nearly everyone else, even most doctors, are reluctant to discuss.

“How long do you have left?”

“I have no idea,” Rine says. “I try not to think about it.”

Rine has spent three years doing what he can to save the lives of firefighters, but he’s more interested now in trying to save people with his profound faith.

His frequent appointments with Holdren in the small studio are more about faith than ink. He sits in the chair for about 25 hours over the spring and summer of 2017, and the two believers spend most of that time explaining how and why they surrendered their lives to Christ.

They match each other Bible verse for Bible verse, and they share personal stories about how faith guided them through the dark times.

Rine hasn’t been mad at God in the five years of his cancer fight. Getting terminal cancer is the best thing that ever happened to him, he says.

It finally made him the person he was supposed to be, the person he never thought he could be.

But there’s still more work to do with his firefighting brethren.

And he plans to use his favorite Bible verses, those tattooed on his arm, to guide him for whatever time he has left.

“And only God knows how long I’ll be around to help,” Rine says.

Matthew 7:7 “Seek and you shall find”

For more than two years, Mark Rine helped as statewide union leaders fought for passage of a law in Ohio that now makes it possible for firefighters diagnosed with cancer to receive compensation for themselves and their families.

He spent hundreds of hours researching the cancer threat. He testified in front of lawmakers at the Statehouse and participated in uncounted meetings during which city and fire officials debated how the law would be worded.

He did it all to help other firefighters and their families, but he also wanted to protect his family upon his own death.

Gov. John Kasich signed into law a presumptive cancer bill at the beginning of this year and it went into effect last April. Since then, 29 firefighters or the families of deceased firefighters have filed claims. Of those, the Ohio Bureau of Workers' Compensation has denied 10 and approved 13, and six cases are pending.

The law says that firefighters who contract cancer are presumed to have gotten it from the job. If they win their claims, firefighters can receive compensation for lost wages and disability benefits, and their families can receive death benefits.

Rine's own claim under the presumptive cancer law was filed in early August. He received a letter from the Ohio Bureau of Workers' Compensation saying it had been approved. But then Rine learned that the city of Columbus had appealed his case.

The law states that firefighters must have been working on hazardous duty and exposed to high-level carcinogens for at least six years for their cancer diagnosis to be eligible. Rine was 87 days short. Unless he eventually wins in the appeals process, his wife and five children won't receive about $1,000 a week in benefits after he dies.

Other states with similar laws have a five-year requirement, but Rine said he never thought about the math of his own case while helping pass the law.

"This will have a huge impact on my family; it feels like someone spit in my face," he said. "I believe in doing what is right. And if they believe it's probable that my cancer was caused by fighting fires, then my family should get those benefits."

Want to participate in the conversation? Check out what's being said.

There are 36 states that have passed a presumptive cancer bill for firefighters, despite some critics who question whether firefighters and the media are exaggerating the cancer risk.

“Studies don’t consistently bear out a strong enough association of causation for firefighters,” said attorney Kris Kachline, who represented the Ohio Municipal League and spoke out against the presumptive bill. “It’s necessary to look at the individual to determine causation and the background of the firefighter to determine causation.”

But those connected to firefighting are thankful the law is in place and hope it can help families deal with their loss.

For decades, that wasn't the case.

Missy Collier lost her husband, Jeff, to occupational cancer. Jeff Collier, a firefighter for Plain City and Washington Township, died in 2006. He was 40 years old.

Missy realized she needed to protect their three boys and wanted to keep their ranch home just outside Plain City.

Doctors employed by his state pension fund denied her claims that Jeff got cancer from his job. Missy couldn't find an attorney to take her case.

She decided to gather evidence of the hundreds of fires that Jeff had fought. Missy went station to station gathering reams of paper from departments willing to help. She found Jeff was exposed to more than 50 carcinogens. The pension doctors later approved her claim, allowing her to keep the house.

“It was a nightmare,” Missy said. “Ten years ago, we didn't have this bill to protect us. They have that now, but who knows how it's going to work."

Mark 8:36: “What good is it for someone to gain the whole world, yet forfeit their soul?”

No one among the 40 or so relatives and friends in the Rine kitchen is singing "Happy Birthday" louder than the guy in jeans and a blue faded hoodie.

Mark Rine is worried that it might be the last time he ever sings that song to one of his children.

It’s nearing the end of a chemo treatment, but Rine has spent two days slow-cooking barbacoa beef, cooking his famous cowboy beans and baking white-frosted cupcakes — his daughter Shelby's favorite meal. It was her 14th birthday.

Birthdays are a big deal in this house. Rine assures it. The birthday boy or girl chooses a menu for a family dinner that Rine prepares. It’s followed by a big party for extended family and friends, and $100 in cash as a gift.

But this one feels different. Rine's body isn't letting him enjoy the moment. His leg hurts. He can barely sleep most nights and his anxiety is rising. And he doesn't know why.

This might be his final chance to light the candles.

He hides his anxiety while children run circles around him, waiting their turn for scoops of ice cream. Rine is good at hiding his feelings and masking his exhaustion. And then it comes, from one of his wife’s friends: his least favorite question.

“How are you feeling, Mark?”

His trademark answer is simple: "I have no complaints." Rine wants to be all things to all people, and he hates to cause worry. This time, he offers his trademark sarcasm instead.

“You want me to lie?” he says. “You want me to sin?”

He quickly wraps his arm around her, apologizes and keeps on scooping ice cream.

Hebrews 12:1-2 “And let us run with perseverance the race marked out for us.”

The Marine inside the Boston fire chief comes out quickly as Joseph Finn paces around the ballroom packed with firefighters, chiefs and business leaders who specialize in protective fire gear.

Finn tells the firefighters at the Boston Convention and Exhibition Center that they need to hold themselves more accountable and combat the fire service’s biggest killer.

Some firefighters blame the cancer epidemic on their stubborn culture.

"Bullshit," Finn says. “Everybody from the chief of the department to the command staff: It’s your responsibility to make sure people are following best practices."

Some inside the fire service say not enough has been done to protect firefighters from cancer. Others argue that they have made strides. But it was evident in Boston this past summer that many inside the profession now take the threat seriously. It was the first time the National Fire Protection Association had made cancer prevention a major topic at its national conference.

The International Association of Fire Fighters announced that it was adding 196 names to its memorial in Colorado Springs, Colorado, which honors those who died in the line of duty.

Of those, 153 died of cancer.

There is no national database of firefighter deaths from cancer. In September, the U.S. House of Representatives passed the Firefighter Cancer Registry Act, a bill meant to help log and address cancer in the ranks.

If the bill is eventually approved, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention would be required to create the registry and study the effects of cancer for volunteer and career firefighters.

The bill is now making its way through the Senate.

Since 1990, nearly 200 Boston firefighters have died of cancer. There is a new cancer diagnosis in Finn's department every three weeks.

Because of this, Finn takes a hard-line stance with his firefighters if they are not following strict cancer-prevention rules that he's implemented.

“I tell my captains and my district chiefs, if I see a guy not wearing his SCBA (self-contained breathing apparatus) during overhaul, I will write you up,” he said. “I’ve told them all and they know it.”

The cancer threat is an even bigger issue in other countries where some firefighters run into massive fires wearing street clothes. Col. Cassio Roberto Armani, commander for the Sao Paulo State Fire Department in Brazil, came to Boston to get ideas and help for his department.

Fire recently engulfed a 19th-century railway station in Sao Paulo. Hundreds of firefighters rushed to the scene. They didn't have air tanks on their backs and they wore paper masks.

“We have a cancer problem, too,” he tells Fire Capt. Peter Berger of Hallandale Beach, Florida. “We are dying.”

Berger, like Finn, is a speaker at the Boston conference.

After watching six of his firefighters get cancer in a department of 67, Berger decided to make prevention his mission.

He went to graduate school at Oklahoma State University and his thesis was cancer in the fire service. He worked with a group of graduate students and experts to survey about 29,000 firefighters across the country in 2014.

Berger’s survey found 40 percent of those 29,000 respondents said they had some form of cancer.

About 35 percent said they washed their gear after a large fire. Nearly 90 percent said they’ve seen peers not properly wearing their gear.

“You’ve been given the awareness, you are aware of the problem,” Berger tells the room. “Change is a very bad word in the fire service and so is cancer, and both of those are unacceptable.”

On Sept. 26, three months after he spoke in Boston, Berger had surgery to remove cancer on his skin after he noticed a painful growth at the base of his neck.

Matthew 7:7 "Knock and the door will be opened to you."

The skinny freshman quarterback scrambles to his right, avoids two charging linebackers and flings a perfect spiral 30 yards into the end zone.

"Money," Mark Rine says quietly, as he watches the ball hurtle through the air and into the waiting hands of the receiver for a touchdown.

Fans of the Granville High School junior-varsity football team roar after Rine's son, Blake, gives their team the lead.

One football mom near the press box yells down at Rine, who is sitting about 10 rows beneath her.

"Hey, Coach Rine," she hollers. "Did you teach him that?"

Rine's smile is as wide as his rain-soaked glasses. The coach for Granville's middle school football teams walks down to the sideline to check on some injured players.

The whispers begin.

How is he doing? How are Heather and the kids dealing with it? Is he going to be OK?

Rine doesn't have the answers almost everyone in his life is seeking.

He doesn't know whether he will get to watch Blake play quarterback for the varsity team or in college someday.

He isn't sure whether he will be able to coach his son Cohen on the eighth-grade football team next year.

He wonders how many more Bible stories he will read to little Halle or whether he will see his teenage daughter, Shelby, graduate from high school.

He knows only that he is still alive today. And hopefully tomorrow.

When he dies, there will be few regrets.

He conquered the demons of his past.

He is a devoted father and husband.

He followed the plan God gave him without questioning it.

He did everything in his power to save his firefighting brothers and sisters.

Now it's up to them to save themselves.

Subscribe nowLike what you're reading?

Stories that inspire. Coverage that informs. Investigations that affect change. This is real news just when it's needed most. This is The Columbus Dispatch. Subscribe today.

Stories that inspire. Coverage that informs. Investigations that affect change. This is real news just when it's needed most. This is The Columbus Dispatch. Subscribe today.

Conversation

Community | Read from the beginning

Community

Firefighters and cancer, a community conversation

Sponsored by The Columbus Dispatch and the Columbus Division of Fire

When: Wednesday November 15, 7 to 9 p.m.

Where: Columbus Fire Training Academy in the John Nance Auditorium , 3639 Parsons Ave., Columbus

Admission is free and parking is available

Moderator: Mike Thompson, WOSU Public Media, chief content director for news and public affairs

Welcome: Kelly Lecker, assistant managing editor for content, The Columbus Dispatch

Panelists: Columbus Firefighter Mark Rine, 36, is the father of five children and was diagnosed with terminal cancer about five years ago. Doctors say his cancer was a result of being exposed to the toxins and dangerous chemicals in the burning materials he battled during his firefighting career. For the past three years he has traveled the country warning other firefighters of the cancer threat.

Nora Jaegly of Toledo lost her husband, firefighter Peter Jaegly, to occupational cancer in 2013. Peter was 49 and served as a Toledo firefighter for 20 years, two as battalion chief.

Missy Collier of Plain City watched her husband Jeff die of occupational cancer at the age of 40. After his death Missy spent years trying to get death benefits from Jeff’s pension fund and from the federal government so she could save the house their three boys grew up in.

Cal Holloway is a firefighter with the Dayton Fire Department and has occupational cancer. Holloway has had several surgeries now to remove cancerous spots from his skin after he underwent a free skin cancer screening.

State Sen. Thomas Patton, a Republican from Strongsville Ohio, spearheaded the passing of Ohio’s presumptive cancer law that took effect in April. The law allows firefighters and their families to file for benefits if they or their loved one was diagnosed with occupational cancer.

Dave Bernzweig, a battalion chief with the Columbus Fire Division and director of health and safety for the Ohio Association of Professional Fire Fighters, has spent years trying to get cancer prevention measures implemented into the fire service. Bernzweig is also a special committee member of the National Fire Protection Association, which helps set policy fire departments across the country follow.

Dale Schulte, chief of the Kalida Volunteer Fire Department, has worked to institute many safety measures that his firefighters follow. The department has 35 members serving an area with a population of about 5,000 people but their old station house doesn’t have a shower.

Mike Wagner, Dispatch projects reporter

Lucas Sullivan, Dispatch projects reporter

Doral Chenoweth III, Dispatch videographer and photojournalist.