CAMERON — Days after the two hospitals in Milam County abruptly shuttered in December, Renee Mueck started feeling stomach pain so sharp she couldn’t drive herself to the nearest hospital about 40 minutes away.

Mueck, 60, said her husband drove her to a hospital in Temple, but her appendix burst before emergency room doctors could operate on it.

“It’s been devastating to everybody because in an emergency now, you have to run to Temple or to Bryan-College Station,” Mueck said. “There’s not a local facility, and it makes it hard on everybody because you never know what you’re going to need emergent care for.”

The hospitals in Rockdale and Cameron, about a 1½-hour drive northeast of Austin, are among the latest hospitals to close in the state, which, because of its size and vast rural areas, leads the nation in rural hospital closures.

Since 2010, 17 of the nation’s 100-plus rural hospital closures — which include facilities that have stopped offering short-term, acute inpatient care — have occurred in Texas, with little sign that the number is leveling off. The hospital in Chillicothe, about 65 miles northwest of Wichita Falls, closed Monday, and the hospital in Hamlin, about 40 miles northwest of Abilene, is expected to close Thursday.

About 16 other rural hospitals in Texas are at risk of closing because of financial difficulties, according to University of North Carolina researchers.

There are about 160 hospitals in small towns across Texas.

Following trends seen across the nation, Texas’ rural hospitals struggle financially because of low Medicaid and Medicare payments from the state and federal governments and the fact that there aren’t enough patients walking through their doors. Not only are rural populations dwindling, but many small-town Texans prefer to drive 40 or 50 minutes to a hospital in a larger city, where they believe they will receive better care than in their own community. Those relying on the smaller local hospital tend to be sicker, older and less likely to be insured, meaning they’re more expensive for the hospital to treat.

Desperate to build revenue, some hospitals have turned to questionable practices, including billing for high volumes of lab tests in apparent violations of contract with insurers.

Research also has shown that states that haven’t expanded Medicaid have higher numbers of rural hospital closures. Advocacy groups, hospital operators and some local officials are convinced that if the state expanded Medicaid, something Texas’ Republican leaders have been loath to do, more rural residents would be insured, lifting some of the financial burden from hospitals, which lose millions of dollars each year in uncompensated care.

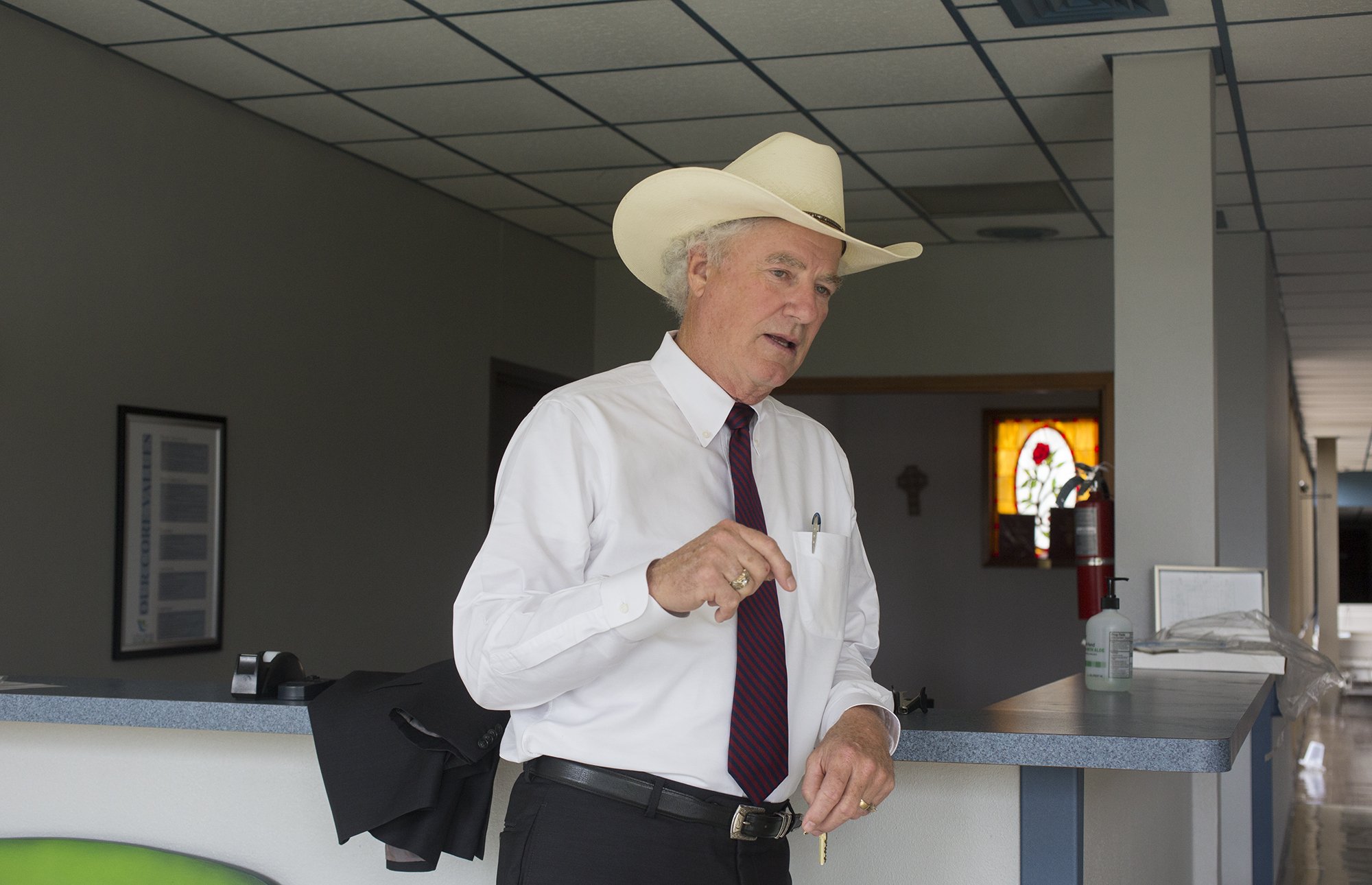

“I would say do it. Why wouldn’t you?” Milam County Judge Steve Young, a Republican, said about expanding Medicaid. “For the time being that we can get it, maybe we can have a hospital here.”

Without a hospital

Grass grows high around the one-story Cameron hospital. Inside, the air is hot and still in the darkened hallways. With most of the expensive medical equipment sold off, carts of gauze and syringes and old hospital beds and chairs are among the few reminders of the building’s original purpose.

Little River Healthcare acquired the Cameron and Rockdale hospitals in 2014 after the previous owner, Tariq Mahmood, was found guilty of defrauding Medicare.

But business proved difficult. The Cameron hospital lost money three years in a row before generating a profit of $3.2 million in 2017. The Rockdale hospital lost $30.2 million that year.

Unable to pay its expenses or find a buyer, Little River Healthcare filed for bankruptcy last July and on Dec. 7 shuttered 18 facilities, including the Milam County hospitals and clinics in Austin and Georgetown. The company reported to the Texas Workforce Commission that it would be cutting hundreds of jobs. Doctors closed up shop, leaving patients scrambling to track them down or to find other sources of care.

Shortly before it closed, Little River was accused of billing insurers for a high number of tests or expensive tests for out-of-state patients, according to the news outlet Modern Healthcare. Claiming Little River had violated terms of their contracts, insurers have refused to pay its lab claims or have tried to recoup money already paid.

At their peak, lab charges made up 86% of the Rockdale hospital’s gross revenue in 2016 and 45% of the Cameron hospital’s gross revenue in 2017.

Desperate to find a way to make money, other rural hospitals across the country have used such lab billing practices, leading to lawsuits and state investigations.

“Little River saw lab services as expanding its ability to sustain losses that it had on other lines of service. You don’t get high reimbursement rates for Medicaid and certain patients,” said Andrea Cunha, the former general counsel for Little River.

Texas rural hospitals lose about $170 million a year on Medicaid and an estimated $50 million annually on Medicare, according to the Texas Organization of Rural and Community Hospitals.

Little River struggled financially in part because it grew quickly, Cunha said. In recent years, the company had acquired two other hospitals — in Oklahoma and the East Texas city of Crockett — and was working to purchase another hospital, also in Oklahoma. In Milam County, the company contracted with a relatively large number of physicians so that patients could receive a variety of services akin to an urban hospital.

The Cameron hospital was already facing closure because it didn’t have enough people staying there to meet federal requirements, Cunha said. The six-bed hospital on average had fewer than one person per day staying for inpatient care, and federal regulations require an average daily inpatient census of two. The average daily inpatient count at the 21-bed Rockdale hospital hovered around three.

Cumulative admissions to both hospitals decreased 42% between 2013 and 2017, which could also be due in part to changes in federal regulations and reclassification of inpatient procedures.

“As I sit here today, I just don’t think there’s any way a hospital in Milam County can survive. We just don’t have the population,” Young said.

Young and the local chambers of commerce are focused on building the county's economy in hopes of attracting more people. The county is still reeling from the closure of an Alcoa aluminum smelter. The company laid off 820 workers in 2008 and eventually shut down the operation in 2017.

Still, the county's population is holding steady. It was home to just over 25,000 people in 2018, according to Census Bureau estimates, a few hundred more than in the 2010 census.

Milam County markets its central location, within a three-hour drive of San Antonio, Austin and Houston — a reason its hospitals saw so little use. Many residents, especially those who recently retired to the area, drive to the bigger cities for medical care. Depending on where you live in the county, larger hospitals in Temple, Taylor and College Station could be less than an hour away.

Cameron resident Lucille Moss, 75, said she received excellent care through the Baylor Scott & White Health system in Temple.

“What we really need is an urgent care facility,” Moss said. The last time she used the local hospital was 10 years ago when she needed stitches after tripping over an extension cord.

'You just continue to hurt'

When Little River closed, 51-year-old Virginia Hubnik’s rheumatoid arthritis doctor also left. The closest specialist is in Waco, requiring her to take a half-day off work for appointments. Recently, she experienced a painful inflammation near her joints, called bursitis, which she endured for months because she couldn’t make the trip to Waco.

“You just put up with it. You just continue to hurt until you have to go,” Hubnik said.

The county’s seniors and low-income residents who don’t have easy access to transportation stand to suffer the most from the hospital closures, multiple residents said.

Nineteen percent of Milam County residents were over 65 in 2015, the latest data available from the Texas Department of State Health Services — more than double the rate of Travis County. Seventeen percent of county residents live below the poverty line, about 4 percentage points higher than Travis County’s poverty rate.

Also read: Officials turned to an election to save Fayette County’s only hospital. Voters said no.

Milam County residents say the biggest impact of the closures is that there is no easy access to an emergency room. Despite total admissions declining at the hospitals, emergency room visits in 2017 were the highest since Little River took over — 9,457 visits between the two locations.

Cameron resident Jean Schara, 58, visited the emergency room the day before the hospital closed because she had fallen off the porch of her home, dislocating her finger. She credits the emergency room in 2015 with diagnosing her husband with a heart condition after his vision started narrowing.

Young, the Milam County judge, visited the Rockdale emergency room once because he had stabbed himself with a fishhook.

John Duffy, 72, credited doctors and other staff at the Cameron hospital with saving his life after he suffered a heart attack.

“They put me on a table, and I passed away and … they brought me back to life,” Duffy said.

The only health care facility remaining in the county is a Baylor Scott & White clinic in Cameron, which offers primary care and lung care, and there are a few physicians elsewhere. A clinic in Rockdale is slated to open Sept. 1, and local governments will help support it through a grant.

Medicaid expansion?

Young said he would support Medicaid expansion because the county budget can’t pay for a hospital and voters don’t want a hospital district to levy property taxes to support one.

Texas is one of 14 states that has not expanded Medicaid, which insures low-income people as well as people with severe disabilities or near-death illnesses, children from low-income families, seniors and pregnant women. Expansion of the federal and state-subsidized health insurance program could cover 686,000 Texans who make too much to currently qualify for Medicaid yet earn too little to qualify for tax credits to purchase Obamacare through healthcare.gov, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation, a policy research organization.

Expanding Medicaid coverage also could make an additional 439,000 Texans eligible for Medicaid, those eligible for Obamacare but just above the federal poverty level.

Having more insured patients would have meant better payments to the hospitals. In 2017, the Rockdale and Cameron hospitals lost $17.5 million to uncompensated care, about 4% of their gross patient revenue. The uninsured rate in the county was 19% in 2015.

“The data is pretty overwhelming that states that took Medicaid expansion have experienced lower percentages of hospital closures because they have measurably reduced their uninsured population,” Dickey said.

Republican state leaders reject Medicaid expansion because they say they don’t trust the federal government to fulfill its promise to reimburse 90% of the cost. Expansion opponents also say the program is riddled with problems, including providing inferior quality of care.

“Medicaid expansion would not solve the crisis we are facing in our state’s rural hospitals,” Sen. Lois Kolkhorst, R-Brenham, chairwoman of the Senate Health and Human Services Committee, said in a statement. “It has been said repeatedly by hospitals that they lose money on Medicaid payments. It is not clear how more Medicaid payments would solve hospital financing issues.”

Don McBeath with the Texas Organization of Rural and Community Hospitals said it’s better to recoup some money from Medicaid than not receive any money from uninsured individuals who aren’t able to pay their medical bills.

The Legislature this year passed a law to require that rural hospitals be paid the full cost of providing care to Medicaid patients. But lawmakers appropriated just $53 million more a year in Medicaid payments to rural hospitals, a fraction of the $170 million they’re shorted in Medicaid funding a year.