People with pain face different crisis when it comes to opioids

Crystal Palmer’s life was on hold.

Gripped by widespread chronic pain caused by fibromyalgia, she longed to be out and about with her husband and kids, to sleep through the night and to work a full day.

Palmer saw rheumatologists, endocrinologists and other specialists. She underwent numerous procedures and tests, and was prescribed medications, including opioid pain relievers. She longed for relief, but also other options — ones without the risks, stigma and side effects of opioids.

“I needed them to get rid of my pain, but I didn’t want them,” the Quakertown resident said.

Palmer didn’t like how they made her feel, and she worried about her son, who is in recovery from addiction.

“I wouldn’t take them,” she said. “I would rather be in pain than to have the medication here in my home. So I suffered. For years, I suffered.”

In the wake of the opioid crisis, new laws, guidelines and other issues with opioid pain relievers mean they no longer are the default choice for patients and doctors. But some are concerned they go too far, and that with limited availability or alternatives, those like Palmer will continue to suffer.

“What we can’t lose sight of is, they are important medications,” said Dr. John Gallagher, chairman of the Pennsylvania Medical Society’s Opioids Task Force. “There is a role for them. And we’re afraid of this pendulum going from one direction … to now we’re starting to go back the other way again.”

The other way, Gallagher explained, was before a national effort in the 1990s and early 2000s to better assess and treat pain. Before that, the risks of addiction discouraged the use of opioids, including hydrocodone and oxycodone developed in the 1970s, unless patients were dying.

But following push back from some doctors on the risks, and marketing campaigns by pharmaceutical companies — which some are now being sued over — the amount of opioids prescribed in the United States began to rise. So too did the number of overdose deaths related to the medications.

The pain pendulum

Opioid prescribing rates peaked from 2010 to 2012, and despite declines in recent years, they still are about three times higher than in 1999, with almost 58 prescriptions per 100 people last year, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Overdose deaths related to opioid pain relievers also remain high, with 46 per day, or 40 percent of all opioid overdose deaths in 2016, according to the CDC.

The challenge now is finding equilibrium, said Gallagher, an OB-GYN in Sharon, Pennsylvania.

“What we stress is the proper use of the medications, low dose, limited for (a particular) purpose,” he said.

That involves reducing the numbers, doses and duration of prescriptions, as well as reducing diversion, or the use by others, and misuse, Gallagher explained.

A recent study by the University of Michigan found the more opioids patients are prescribed after surgery, the more they will take regardless of pain. And while only a fraction of people move from opioid pain relievers to heroin, nearly 80 percent of those who use heroin report previously using opioid pain relievers, according to the National Institute of Drug Abuse. Many also report that they got them from family and friends.

About 60 percent of people have leftover medications and hold onto them for future use, according to a study by Johns Hopkins.

“We need to turn down that pipeline,” Gallagher said.

One of the largest efforts to reduce the numbers of opioids and other medications is the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration’s National Prescription Drug Take Back Day, which occurs twice a year and has collected nearly 5,000 tons of unused drugs as of April.

Yet, there are fewer opioids out there to collect. The number of prescriptions filled in the United States has been declining, and some patients have begun turning them down entirely because of the risks.

Libby Majewski, of Prevention Plus of Burlington County, said turning them down is one of the best ways to prevent addiction, but only if it’s safe for people to do. Majewski’s work focuses on special populations such as veterans, young people and older adults.

Pain is a “huge piece” of some older adults’ daily lives, and combined with other factors, it can put them at increased risk of addiction, Majewski said.

“There is a percentage of the adult population that we see can become addicted to substances as they get older when they have not dealt with addiction in their lives previously … they’re on multiple different medications,” she said. “What we see is it can become a substitute for healthier ways of coping with some of those factors.”

Gallagher explained that sometimes it may be necessary for patients to take opioid pain relievers, for instance, after surgery.

“We do say, you’re going to have some pain and we don’t want you to not be able to move or breathe deeply because you’re in pain and then more problems can occur,” he said.

Such risks and benefits are what the CDC stresses that doctors should weigh before prescribing opioids.

Guidelines and limits

In 2016, the agency released guidelines that provided recommendations for prescribing opioids for chronic pain, except for patients undergoing cancer treatment or in palliative or hospice care, whom doctors can treat as necessary to manage pain. Chronic pain usually is persistent and can affect health and quality of life, while acute pain usually is temporary and triggered by an injury or other cause.

Some states, insurance companies and authorities are going a step further.

New Jersey’s opioid law passed in 2017 included some of the strictest guidelines in the country. It limited first-time opioid prescriptions to five days, except, similar to the CDC, for patients undergoing cancer treatment or in palliative or hospice care. In addition, doctors must follow documentation requirements and have detailed discussions with patients about risks and other options.

Pennsylvania’s prescribing guidelines include recommendations for how to safely and effectively use opioids to treat chronic pain not caused by cancer, and for use in emergency rooms, dental settings and other circumstances and specialties. They are voluntary, but legislators recently considered a bill that would have made them mandatory.

“We think these guidelines are great and we support them,” Gallagher said. However, the medical society opposed the bill. It did not pass before the session ended.

“It really ties our hands,” he explained. “So we want the guidelines and we want physicians to follow them, but the mandates become more difficult.”

Doctors see exceptions all the time, Gallagher said, and they need “wiggle room” to take care of their patients.

Doctors are under “tremendous pressure” to reduce the number of opioids they prescribe and doses their patients take, said Dr. Douglas Gugger, a pain specialist with Pennsylvania Pain & Spine Institute. But he doesn’t think the goal should be to take all patients off the medications.

“There are patients who if I showed you their MRIs or X-rays, they have been through the worst accidents. They live with legitimate daily pain at high levels, and there are those patients that those medications — used responsibly — are important,” Gugger said.

New Jersey and Pennsylvania also require doctors to check state prescription drug monitoring programs to help reduce doctor-shopping and overprescribing.

Authorities are cracking down on doctors who continue to prescribe large numbers of opioids or high doses that exceed guidelines and limits. Some have received disciplinary action or lost their licenses, and some have been charged with crimes, including in cases where patients have died from overdoses.

“Prosecuting doctors under the appropriate circumstances definitely can help in the overall fight against addiction," Burlington County Prosecutor Scott Coffina said. "Doctors who overprescribe opioids without medical necessity are drug dealers, and can be charged with distribution. We recognize that the vast majority of physicians practice responsibly, but those who do not will be investigated and prosecuted when the evidence warrants.”

Gallagher said a growing number of doctors are following the guidelines, but it takes time for any clinical practice guidelines to become part of general use. The medical society has been pushing training on the guidelines and several other topics including opioid education and how to refer people to treatment.

“If I do a (prescription drug monitoring program) review and see the patient has multiple drugs from multiple doctors and it’s suspicious, instead of just saying, ‘Look, I’m not giving you any of these medications,’ my job is to sit and talk to that patient and say, ‘Look, I’m seeing a trend here, are you willing to talk about it?’” Gallagher said. “I think that’s what physicians really need to start (doing) — not just writing people off, but saying we’ve identified the problem, how do we get you (help).”

Physicians like Dr. Stephen Goldfine, chief medical officer of Samaritan Healthcare & Hospice in Burlington County, also use screening tools including questionnaires and urine tests to help identify patients who might be at risk of misuse or addiction, and they employ patient contracts and regularly communicate.

“It’s just being responsible, so as we start talking to patients and giving them medications, making sure they are not filling too early and if they are, we are asking why,” said Goldfine, who specializes in family medicine and hospice and palliative care.

Gugger said it’s important for doctors to communicate with patients who have a history of addiction or who develop one.

“In the past I think we tended to abandon patients with issues, and (now) we do our best to let them know that we’re not abandoning them, there are non-opioid options,” he said.

It can be tricky, however. Goldfine touted a new Rutgers University project that will look at how to treat and manage pain in cancer patients who are in recovery or active addiction.

It can be tricky even for patients who don’t have addiction because of the stigma associated with opioids.

“Some patients, even with cancer, are looked at as being that drug addict and narcotic-seeking,” Gallagher said. “And I’ve had a lot of patients that have felt that frustration and then have had issues with access.”

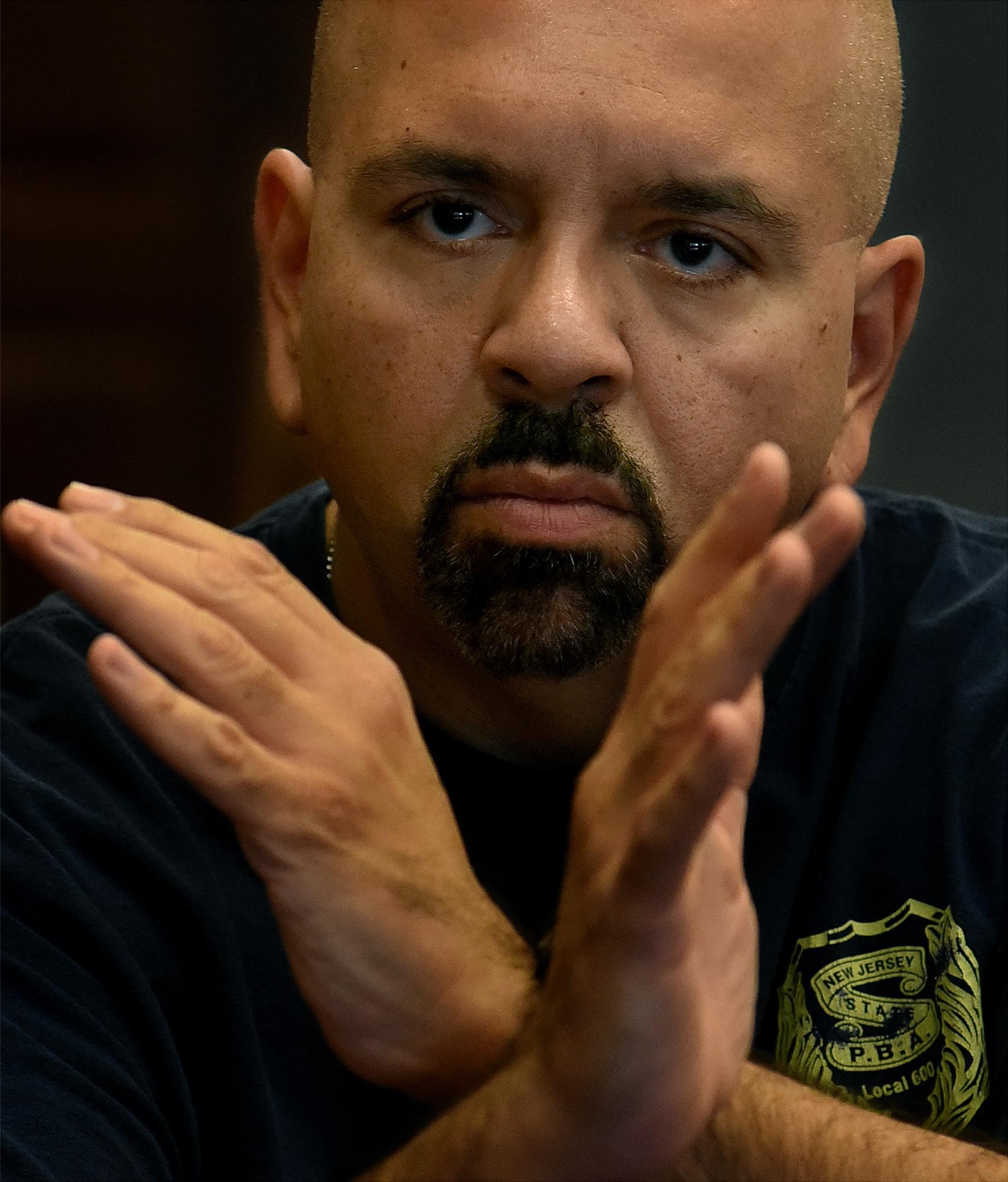

Michael Carroll of Perkiomenville, Pennsylvania, has experienced such issues. He’s had multiple accidents and dozens of surgeries over the last 12 years, leaving him with severe headaches and chronic pain in other parts of his body.

Opioid pain relievers are just one of the options Carroll and his doctors use to manage his pain. They have conversations about the medications and monitor his use, but he’s been called a “junkie” and struggled with doctors in the past to get proper treatment.

“A lot of times, doctors will tell you ‘I’m going to give you this medication’ and then after awhile they can’t give it to you anymore because ‘You have to go to a pain management doctor’ or ‘You have to get it another way’ — you know, they put it that way,” he said.

Carroll said many people don’t believe his pain is real.

“I’m generally around a 6 or 7 mark (on a pain scale of 10), which for me, I try to live with. I wish I could get it down to a 3 or 4. But compared to days when it’s 15, 20, I think it’s somewhat tolerable,” he said.

Palmer agreed.

“A lot of times people think that fibromyalgia was something that was just in your head and it was more a mental problem than it was a physical problem, but what they didn’t understand was it was a little bit of everything,” she said. “For probably for the last 10 to 12 years I’ve slept two to four hours a night.”

Many doctors have decided to stop prescribing opioids altogether. Some have suggested leaving it up to pain specialists and others trained in pain management, like Gugger and Goldfine. The two doctors said their referrals have increased with the opioid crisis.

Some pharmacies also have reduced the amounts of some opioids they carry.

“I had a case ... where we were trying to get some morphine for a patient and the pharmacy didn’t have any in stock. And this was a hospice patient,” Goldfine said.

Patients also have had issues with access because of limits and requirements set by some insurance companies, Goldfine and Gallagher said.

“When we have a cancer patient and we write for medications we often have to get a prior authorization, which can take a couple of days. Once they find out it’s for cancer they’re pretty good,” Goldfine said. But it can cause delays.

The Pennsylvania Medical Society has criticized insurance companies that have set prior authorization requirements for opioid pain relievers that in some cases have delayed treatment or sent patients into withdrawal.

“The insurance companies mean well, but the restrictions they put on are possibly going to hurt patients more,” Gallagher said. “Everybody wants a quick fix and there’s no such thing in this problem.”

It can be difficult and take a long time to reduce high doses or long-term use, Gallagher explained.

“They’ve been on opioids for back pain for the past 20 years — nobody’s done anything different — and if you sit there and say, ‘I’m just going to stop prescribing,’ that patient could be driven to heroin or something else because they’ll go into withdrawal and they don’t want that to happen,” Gallagher said.

However, many people feel better in the end, Gallagher said, because long-term use of opioids actually can cause an increased response to pain.

“So, they feel better coming off as long as you substitute it,” he said.

Support is also important, Goldfine said.

“One of the other things in terms of non-narcotics is having a good social support, good counseling, making sure the patient is not anxious or depressed,” he said.

There are more and more options that don’t involve opioids or aren’t medications at all, Goldfine said. However, access to those also can be a problem, Gallagher added.

Options and alternatives

“There’s acupuncture, physical therapy, chiropractic, hypnosis — there’s all these things out there,” Gallagher said. But, depending on insurance, such options aren’t always covered the way opioids are, he added.

Independence Blue Cross recently announced to doctors and other providers that in 2019, it will begin covering acupuncture for some conditions including low back pain, pain from arthritis in the knee or hip, and chronic neck pain. The insurance company has long covered other options like physical therapy, occupational therapy, certain types of injections and even implantable stimulators, Dr. Ginny Calega, vice president of medical management and policy, added.

Gugger said doctors have to be more open to other options. In his practice in Bucks County, they use a “multidimensional approach to pain.”

“We employ everything at our disposal,” he said.

That includes medications and other treatments like physical therapy, acupuncture, chiropractic adjustment, medical marijuana and even cognitive behavioral therapy.

“That’s a hard sell for a lot of these patients — that they need to look inward and maybe involve some of their family members,” Gugger acknowledged. “But we know from research that it takes those different angles of approach to improve pain scores.”

It’s sometimes unclear which comes first, but pain and anxiety or depression are often linked, Calega said.

“If you’re feeling anxious or depressed, your threshold for feeling pain goes down and as you start to control those symptoms your threshold for pain goes up,” she said. “That’s why it’s so important to treat them at the same time.”

The insurance company has been partnering with doctors and other providers to better integrate physical and behavioral health care in the same settings. And on Aug. 1, it began offering its members free online screenings and cognitive behavioral therapy tools.

For example, Calega said, “If you have insomnia — how can I get back to sleep? There’s a web-based module you could do in the middle of the night if you want to,” she said. “There's definitely literature that shows the cognitive behavioral therapy — once people graduate from a program, if they continue to do the techniques — it does have long-term benefits.”

Majewski, of Prevention Plus, developed a toolkit with resources and information in Burlington for people who have pain and need other options and alternatives to opioids.

“I think that we have to really explore and give options for them to be able to say, ‘I’m not going to fill that prescription’ or ‘I’m going to take a couple days worth and get rid of any remaining meds and seek out some of these alternative methods,’” she said.

One of the resources in the toolkit is Siobhan Hutchinson of Next Step Strategies. She has a master's degree in holistic medicine and uses her knowledge of techniques including energy medicine, Reiki and T’ai Chi to help people feel self-empowered when it comes to their bodies and issues like pain.

“With all of my clients I tell them right up front — in fact, I even have them sign a consent form — I am not a medical doctor nor do I claim to be. I don’t call myself a healer, I call myself a holistic practitioner. And I cannot diagnose them, I cannot cure them,” Hutchinson said. “But what I can do is share what has helped me personally and my knowledge of different techniques to try to see what may help alleviate some of their symptoms.”

Recently, she’s had more clients come to classes in Burlington, Bucks and other New Jersey counties who were referred by their doctors for issues like pain.

“We have to be practical. We have to use both eastern and western (medicine)," Hutchinson said. "The doctors are seeing that and they’re also espousing self empowerment, for the patient — in my case the client — to take self care.”

With the help of her doctor, Palmer found freedom from her pain through medical marijuana, which is now available in Pennsylvania and New Jersey.

She got a recommendation from Gugger and got her card and her first dose in mid-August. For the first time since she was diagnosed with fibromyalgia in 1999, she was pain free.

“I’m such a different person now,” she said. “It’s slowly happening — I’ve lost 16 pounds, I’m sleeping at night, I’m able to go out and walk and be active.”

“We go places, we do things, I’m not hurting, I’m not tired, I’m not waiting around for that pain to happen,” she continued. “I feel like I can be me again.”