Access, stigma an issue when it comes to medication-assisted treatment

People have told Rob Hardcastle that he got over his heroin addiction by “trading one drug for another.”

But on his new drug of choice, he’s not waking up convulsing from withdrawal and cursing God that he’s alive.

On this drug, he’s not stealing from his parents, retail stores or friends to feed a $100-a-day addiction. He’s not waking up in emergency rooms after a heart attack, car accident or an overdose.

Yes, he’ll tell you, he did trade one drug for another. And it saved his life.

The drug was methadone. It’s opioid-based, but when taken as prescribed, it doesn’t produce a euphoric high. Instead, it stops the pain of withdrawal and — most importantly for Hardcastle — eliminates the cravings.

And when combined with treatment including one-on-one counseling and group therapy at Aldie Counseling in Doylestown Township, it finally helped Hardcastle achieve recovery.

“I remember doing fine for a few days in rehab, but then the drug would call you, and your mind gets to a point where it’s all you think about; you crave and crave, like you’re starving and you need it (heroin) in your system. That’s what an opioid does to you,” the 48-year-old Doylestown Borough resident said.

“Without the cravings, I feel like I could finally actually concentrate and hear what the counselors were saying,” he added. “And I started listening, because at this point, I had tried it every different way and nothing ever worked.”

Methadone is one of three drugs approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for use in medication-assisted treatment, or MAT. It’s exactly what it sounds like: the use of medication to help people in treatment.

“Medication is a tool; it’s not a silver bullet, but it’s a tool that allows the brain to heal and the individual to work toward recovery,” said Jason Snyder, former special assistant to the secretary of the Pennsylvania Department of Human Services.

Standard of care

Mounting research supports the benefits that Hardcastle experienced with MAT, and it’s now considered the “standard of care” for opioid use disorders. And that’s been leading public officials, treatment programs and others to work to increase access to MAT and reduce the stigma associated with its use.

With all medication, people suffering from substance abuse disorder simply can’t show up at a hospital or treatment facility and expect to receive a dose the minute they walk through the door. At Aldie, for example, it may take a few days to go through the intake process, where patients are assessed and a clinician determines what medication, if any, is advised.

Methadone, for example, is only dispensed in a clinic but that means patients have to make the trip on a fairly regular basis — daily, in the beginning.

Hardcastle knows that some places don’t offer counseling or some type of support with the dispensing of methadone. “There are some (methadone) clinics — they call them juice bars — and you’re allowed to take other drugs. Aldie doesn’t allow that.”

Those places exist, but it’s the combination of medication and treatment, including counseling and therapy, that makes the difference, said Pooja Shah, a nurse practitioner and the former medical coordinator at Livengrin Foundation in Bensalem. Livengrin offers MAT using naltrexone, also known as Vivitrol.

“If we are treating patients alone with medication their chances of relapse are higher. If we are giving them just the therapy, it does not work as well,” Shah said.

“Very rarely have we seen someone make a long-term recovery without the use of some form of MAT — even if it’s temporary,” added Julie Williams, clinical director at the Penn Foundation in West Rockhill.

Penn Foundation offers everything from long-term inpatient to outpatient therapy, and the average length of stay there is six months. But of all the programs, outcomes are better among those in MAT using Vivitrol, or MAT using buprenorphine, also known as Suboxone.

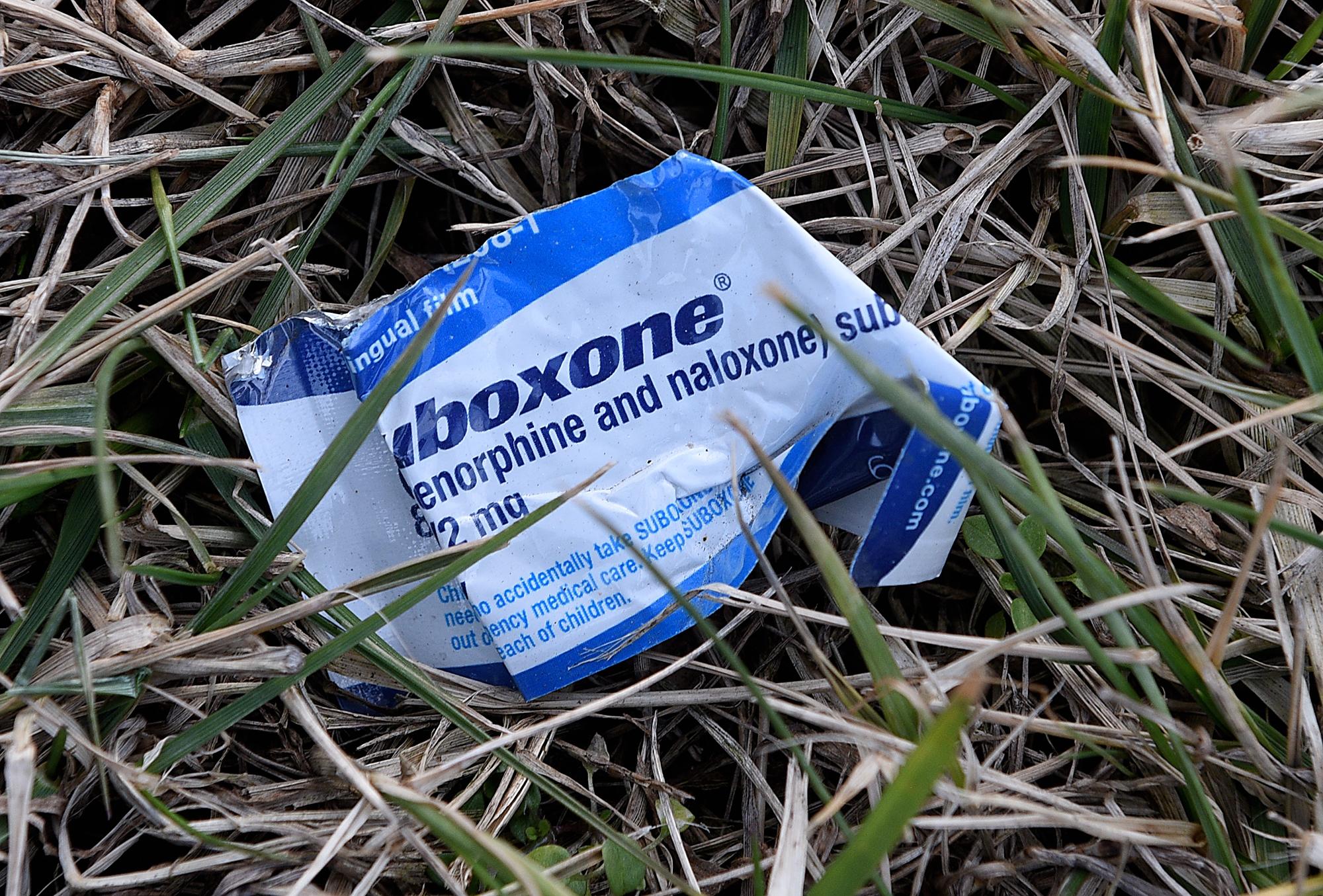

Suboxone is opioid-based, so dispensing also is strict because it can be misused or sold on the street. Physicians must go through training and receive a waiver from the federal government to prescribe Suboxone.

“There’s a lot of diversion,” Williams said.

In recent years, the FDA also has approved Sublocade, a once-monthly buprenorphine injection, and Probuphine, an implant that delivers buprenorphine for up to six months, both of which eliminate the need for daily doses of Suboxone and opportunities for abuse or diversion.

Vivitrol, on the other hand, is not an opioid. It works by blocking opioid receptors in the brain and has been described as a bulletproof vest against the drugs. Even if people use, they won’t get the euphoric high. However, they can still overdose on opioids if they use too much.

“The reason you use is why? To feel good, to have that euphoria, so if you’re not having that, what’s the point of using?” Shah said.

Vivitrol can be taken daily like methadone and Suboxone, or injected monthly. The injectable form has a higher compliance rate, but it’s also more expensive, Shah said. People also must detox completely before taking it, because of the risk of severe withdrawal symptoms.

Livengrin now averages about 80 injections a month between people in inpatient rehab and outpatient treatment — and it’s working, said nurse manager Donna Walter.

“I’m seeing people staying in treatment longer, I’m seeing them staying clean and sober longer,” she said.

Part of plan

Shah said they still have to work on their recovery.

“Anybody who feels like they need that extra push to stay in recovery, this would be a good treatment plan to use,” Shah said. “I always tell my patients that this is an extra safety net. It’s not an answer to your recovery, but it’s an extra tool in your recovery belt.”

Determining what form of MAT to use just depends on the individual — methadone might work better for one person while Suboxone works better for another. And while Vivitrol use currently is limited to a year, people can take the other forms for several years, or even the rest of their lives.

More treatment facilities are beginning to offer MAT, but some have resisted it — particularly Suboxone and methadone — because of the stigma that “you’re not really clean” or “you’re depending on something” for recovery, explained Dr. Michael Shore, an addiction psychiatrist and leader of the medication assistance recovery program at Malvern Institute in Cherry Hill, New Jersey.

According to a Health Affairs analysis of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s 2016 National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services, out of more than 12,000 treatment facilities in the country, only about 4,950 offered at least one form of MAT, and fewer than half of those offered two or more forms. Just 319 offered all three forms.

“We can do a much better job in the treatment industry,” said Shore, who also is the director of the American Society of Addiction Medicine region that includes Pennsylvania, New Jersey and Ohio.

Because of the stigma, Snyder said people also do not always get information about MAT, or referred to treatment providers that offer it.

“You would like to think that provider bias does not exist, but it does,” he said. “I have personally seen where maybe subtly or not so subtly, an abstinence-based provider will try to steer people into abstinence-based treatment.”

Snyder recalled the story of a mom he met during his time with the state. Her son died of an overdose after being in treatment for 30 days, and she wondered if he would still be alive if he had stayed longer.

But Snyder wondered if he would still be alive if he had been offered naltrexone or a similar medication -- “knowing the high risks for somebody who has 30 days of abstinence, knowing that fentanyl is out there being passed off as heroin. And one bad bag can be deadly. If you leave treatment and do not have medication, the likelihood that you will potentially relapse and overdose is great,” Snyder said.

Access to MAT “really stuck out” to Snyder, who now is regional director for eastern Pennsylvania for Pinnacle Treatment Centers, which has a location in Quakertown and Mt. Laurel, New Jersey.

“I thought, man, we’re wringing our hands about the number of deaths we have every day here in Pennsylvania, and it’s not this cut and dry, but it seemed to me we are not taking advantage of what could be one of our most effective tools in treatment,” he said.

There have been significant investments in MAT since then, including as recently as mid-July, when Gov. Tom Wolf awarded three $1 million grants to organizations, including Temple University Hospital, for efforts related to the Pennsylvania Coordinated Medication Assisted Treatment program, also known as PAC-MAT.

“PAC-MAT provides for a hub-and-spoke model of treatment with an addiction-specialist physician at the center of the hub and primary-care physicians serving as spokes to provide treatment directly to patients in their own community,” Pennsylvania Secretary of Health Dr. Rachel Levine said in a statement.

Earlier this year, New Jersey officials also announced Gov. Phil Murphy planned to spend $56 million on prevention, treatment and recovery, including expanded and improved access to programs such as MAT.

Melinda Goodwin, director of clinical programs at Aldie, said additional steps also need to be taken to “de-stigmatize” MAT in the medical and criminal justice fields.

“MAT isn’t a personal belief system; it’s backed up by science,” she said.

Goodwin's clinic gets many referrals from probation officers and police, but she said there are still some in the criminal justice system who will mandate people go to inpatient rehab and an abstinence-based 12-step program, without mention of MAT.

While some 12-step programs allow medication-assisted treatment, others prohibit it as part of total abstinence. Goodwin wishes hospitals also would give people information about MAT before releasing them after an overdose or when they come into the hospital in withdrawal.

“We would like to reach out to ERs to identify high-risk individuals who are at an increased likelihood of overdose or cycling through the system again and again and again,” Goodwin said. “Lives could be saved, which would also reduce the financial impact of the opioid epidemic.”

MAT doesn’t always work for everyone, like Phil Bacino, 35, of Riverside. He struggled with addiction for years and tried both Suboxone and methadone before finding a different way to achieve recovery through intensive outpatient and outpatient counseling.

“It was just a Band-Aid,” he said. “Methadone (is) just a Band-Aid. It works if you work it.”

But it worked for Hardcastle, who is now a peer counselor at Aldie. Five years ago, he stood in a dark corner of his mother’s home clutching a knife and thinking of ending his life.

With the guidance of a friend and the support of his mother, Lynne Hardcastle, he turned to Aldie. And slowly, he found his way back to a relationship with his family, sober living and volunteerism in his community.

“Me and mom go to family therapy, twice a month,” said Hardcastle, who hasn't touched heroin in five years and is now leading peer support meetings at Aldie.

“To me it’s a life-saving medicine,” he said. “People don’t frown on cancer patients going through chemo. I have an opioid disease and this is the cure for me. My life is 100 percent better. I’m actually having a life now. I’m not depressed and wanting to die and doing all the other bad things that come with addiction.”