If Joe Frank Martinez, head football coach at South Austin’s Travis High School, could knock off a few items from his wishlist, he would have new helmets for his players, replace the decades-old equipment in the weight room, and feed his freshmen more than turkey and cheese sandwiches the coaches assemble before games.

Equipment and catered meals don’t necessarily win games, Martinez says, but he knows if he had a few more dollars to better train and feed his boys, he’d have a better shot at winning games. Last year, the varsity team didn’t win any games. The team won one game the year before.

“It’s almost not even fair. You’re going to have all these lack of resources and on top of that you want me to win? A lot of times we’re just trying to survive,” Martinez said.

Coaches at low-income high schools told the Statesman that they believe their players possess the same degree of natural talent as those at higher income schools, but because of poverty-related challenges, their players have a harder time realizing their potential. Among the barriers high poverty schools face:

• Students don’t arrive on campus with as much athletic experience because their parents can’t afford expensive sports camps or leagues.

• Students can’t commit as much time to athletics because they are working jobs or caring for siblings.

• Team meals are often simple and equipment worn out because those are paid for and maintained by limited school budgets and in some cases by coaches. At wealthier schools, booster clubs help cover those expenses.

• Coaches have a harder time recruiting players from within the student body.

Darrell Crayton, who retired from Eastside Memorial High School, a high-poverty Class 4A school, but occasionally helps out with the Reagan High School football team, said having separate championships for urban schools, most of which have disproportionately large numbers of low-income students, is worth considering.

“I saw a lot of kids that didn’t believe in themselves and sometimes they felt they accepted defeat. I think that the kids wanted to (win) and they do try hard, but things have just not been available to them,” Crayton said.

‘Not part of something big’

Within 20 minutes, Martinez and fellow Travis coaches have slapped together 72 sandwiches, methodically placing two slices of turkey and a single piece of Kraft cheese in between H-E-B extra-thin white bread.

While players at other schools dine at local restaurants, Travis football players for years have eaten sandwiches before games — handmade ones for the freshmen and six-foot subs from Walmart or Sam’s Club for the older players. Last year, a local nonprofit Positive Coaching Alliance started providing catered sandwiches for the varsity team.

The Austin district provides schools with just enough money to pay for the basics, including jerseys, cleats, padding, helmets, and school buses to travel to away games. Coaches use fundraisers or their own money to pay for extra expenses.

“I’ve maxed out credit cards before,” Martinez said. “If I don’t get the money back, then so be it. It’s something that we’ve got to do. Other coaches around here and other programs whether it’s band, dance and cheerleading, are doing the same thing.”

The school doesn’t have a football booster club, so Martinez helps coordinate three fundraisers a year, which typically bring in $1,000 to $2,000 each. In April, alumni helped raise $4,000 through a golf tournament. Whatever Martinez and his players raise is used to buy snacks and meals during away games for players, fixing equipment or paying for training coaches must complete to maintain certification, among other expenses.

Martinez is hoping he can raise between $10,000 to $15,000 to remodel the weight room, which decades ago was the campus’ automotive shop. Now, it contains 14-year-old incline benches with tattered fabric covers and 20-plus year-old squat racks with chipped wooden platforms.

“There are certain schools that have resources that we don’t. We have a school in our district that has a turf field and lights because their parents were able to pay for it. If I were at the school, I would take advantage of that … but that’s a major disadvantage for the other campuses,” Martinez said.

He and Crayton also note that the quality of players might be better at other schools because their parents have paid for them to join football leagues at a young age or participate in camps during the summer.

Because high-poverty schools aren’t winning as many games, Steven Lopez, Travis’ varsity quarterback, said the players do not receive as much of the public’s attention.

“Kids that don’t have as much money feel like they don’t mean as much, they’re not part of something big like Lake Travis or Westlake. We don’t get looked at as much because of where we’re at and who we are,” said Lopez, 18.

Community support

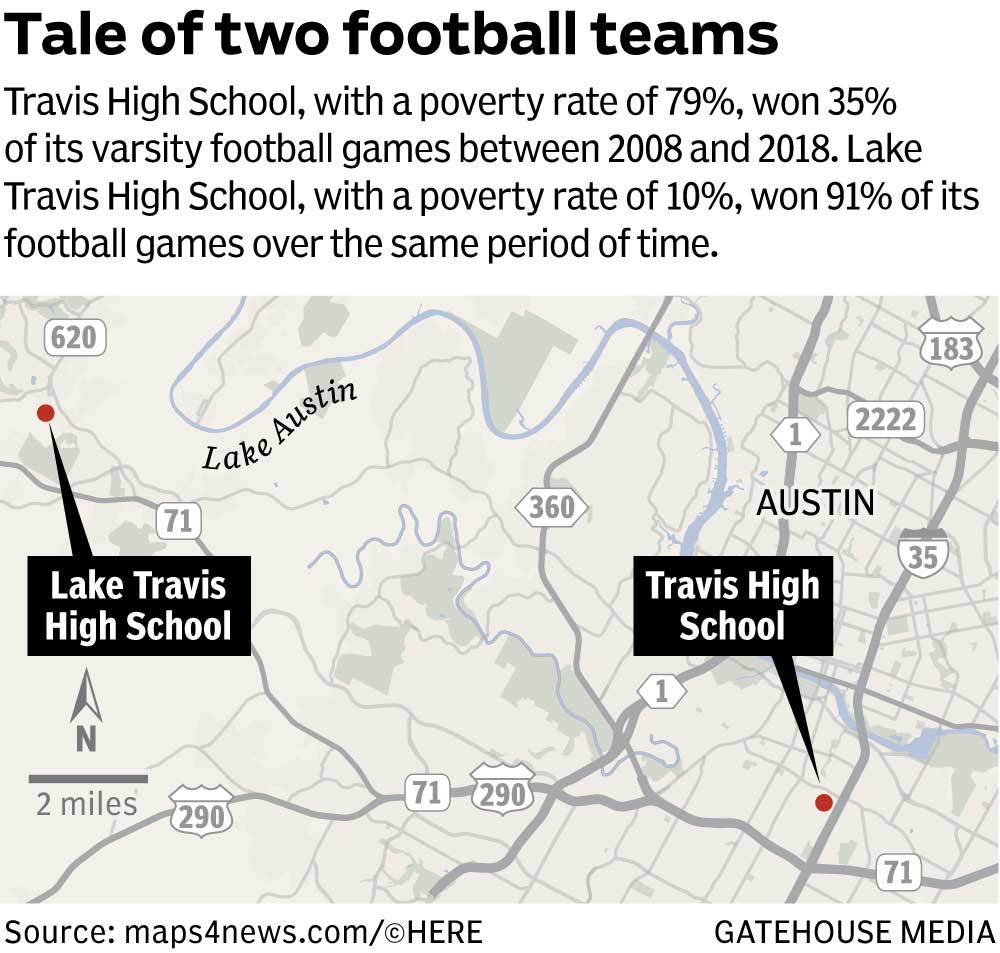

Nineteen miles away at Lake Travis High School, where 10% of students are low-income, amenities are newer and on a much bigger scale thanks in part to the wealthier community. Lake Travis has won 91% of games, including five state championships, between 2008 and 2018.

The parent-run booster club organizes a before-game event in front of the high school called the Cav Zone where students and families can dine at food trucks, listen to a DJ and play games. The club also pays for the coaches’ meals on Thursdays and Saturdays, charter buses for away games and the replacement of helmets every four years instead of the standard 10 years. Because a football player last year said it’d be cool to run through a fog machine, the club found a machine to put underneath the inflated tunnel football players run through when they’re introduced at games.

Each of the booster club’s three major fundraisers generate on average more than $50,000, said Gabe Ellisor, president of the booster club.

The community also has backed bond referendums over the last several years that have helped pay for an indoor turf facility and new equipment for the weight room. Bond dollars also paid for the 8,000-seat stadium, which draws near-capacity crowds that are far larger than home games for lower-income schools.

“The community continues to love football and success breeds on itself,” said Ellisor said. He and other parents who volunteer for the booster club have known each other for years, since their kids were participating in recreational youth football through the Lake Travis Youth Association.

Ellisor credits the players and coaches for winning games but he and district officials recognize the role the community and parents play in the success of the football program.

“It allows the coaches to focus on the games and focus on their players when they know the booster (club) and the school district have the details worked out and not just us, but the community support and business partnerships,” said district spokesman Marco Alvarado. “Not many districts are as fortunate.”

Attracting enough players

The lack of affordable housing and growth of public charter schools have whittled away at the Austin district's enrollment, hitting high poverty schools the hardest and making it difficult for coaches to attract enough student athletes.

Multiple Austin schools have had problems filling their teams with football players this year, running the risk of overplaying athletes who want to play.

Martinez, who struggled to field the junior varsity team this year, said he’s had students who live nearby attend summer practices and on the first day of class show up at another school. Students who live in poverty tend to move more often than students from wealthier families.

Also, responsibilities at home can prevent students from joining sports teams, Lopez said.

Lopez, too, sometimes struggles with balancing responsibilities to his team and to his family. When his parents are working — his dad is a house painter and his mom works at JC Penney – he’s expected to babysit his younger siblings or drop them off and pick them up from school.

“I tend to … be there for my team,” Lopez said. “If I focus on here and school more, I can make it out there and make my parents more proud and actually help them.”

High-poverty LBJ High School is an outlier — its football team won 61% of its games between 2008 and 2018 — but coach Jahmal Fenner said the school also faces challenges attracting players. Families can find newer schools and bigger homes at more affordable prices in the suburbs, sapping students from Austin, Fenner said.

LBJ faces the additional challenge of being placed in a higher division of schools with larger student enrollments because LBJ shares a campus with Liberal Arts and Science Academy, a magnet program. Few LASA students participate in football, Fenner said.

“No, I don’t think the classification is fair, but we can gripe about it and not prepare our kids or we can raise our levels,” Fenner said.

Fenner attributes the relative success of the LBJ football program to the longstanding tradition of the sport at the school as well as strong coaches who have experience playing in college. The coaches provide individual attention to the players, encourage them to play multiple sports, and encourage athletes to mock up and publicize recruiting reels.

To attract students to LBJ, Fenner promotes the academic programs of the school, like the fact students can earn an associate’s degree through the school’s early college program.

“This is my philosophy,” Fenner said. “First, as a parent, you need to make a decision for your kid that is academically going to help them be successful. I don’t necessarily look at the athletics side of it. You have to look at the academics as well.”

High-poverty division?

Crayton, the former Eastside Memorial coach, said he would like to see a separate championship for urban schools because he wants every school to have a shot at winning the big game.

Other states have grouped high-poverty schools into seperate divisions, but multiple Central Texas coaches said it would be difficult to implement in Texas because of the state's size.

Currently, all Texas high schools are grouped in divisions based on their enrollment and geographic location. Coaches said they fear by playing teams based on socioeconomics, teams would have to travel far for games, which would be costly.

Students who attend high poverty schools also don’t like the idea of being lumped together.

Lopez, the quarterback at Travis, said he doesn’t want to feel like he’s not as good as the players at wealthier schools.

Joe Lopez, quarterback at Crockett High School, with 67% of students from low-income families, agrees.

“There’s no team that I would say, ‘Hey, don’t put us against them,’” he said. “I believe that with the work I put in, my team and my coaching staff has put in, there’s no team that I look at and have a shadow of a doubt that we can win.”

Martinez and Fenner said it would be nice to win all the time, but they instead try to focus on factors they can control, like instilling positive values and ensuring players become productive adults.

“Obviously, nobody enjoys losing, but I think there’s different ways that we can all grow and be winners,” Fenner said.

Multiple coaches also say improvements to the school finance system could level out the resources of sports teams.

Martinez blames the lack of resources at many Austin schools on the state school finance system that forced the district to pay an estimated $670 million to property-poor districts last school year. While neighboring districts like Del Valle and San Marcos have passed bonds to build modern stadiums, the cracked tennis courts at Travis are barely useable, the air conditioning breaks down in his athletics department, and the practice field doesn’t have lights, forcing players to sometimes practice in the dark later in the season, Martinez said.

House Bill 3, passed by the Legislature this year, is expected to decrease the Austin district’s recapture payment by $193 million in 2020. The district also is proposing closing schools in part to save money.

“When we’re sending over a two-year period a billion dollars … to other school districts that are considered needy and we have our schools that there are times we can’t have hot water for our kids and the A/C has been broken for three days … it’s a major disadvantage to our kids,” Martinez said. “I’m not a politician and I don’t have an answer, but that’s definitely not it.”