Uneven preparation

As waters slowly rise along Florida shores, coastal communities’ approaches vary

By Dinah Voyles Pulver, dinah.pulver@news-jrnl.com

Tom McLaughlin, tmclaughlin@nwfdailynews.com

Dale White, dale.white@heraldtribune.com

As rising sea levels cause flooding more often in Florida, the state’s first city has a concern as old as civilization itself.

“If there’s one thing that’s absolutely certain, people expect their toilets to flush,” St. Augustine Mayor Nancy Shaver said. To guarantee that, the city will need to find a way to keep its sewage treatment plant above water.

As the ocean rises, the outfall for the plant — on a marsh along the San Sebastian River — is “no longer going to fall out,” said Shaver. “You-know-what doesn’t run uphill, and we have a gravity sewer system. If it can’t run downhill, it’s not going to function.”

Protecting St. Augustine’s most vulnerable asset, she said, could cost as much as $100 million, twice the city’s annual budget.

Local governments all around Florida’s coast could face similar realities, with storm drains, causeways and other crucial facilities at risk. For some, the costs could be staggering. Rising water also threatens revenue from tourism and high-value waterfront properties.

Forecasts from federal scientists say the expansion of warming oceans, coupled with the addition of water from melting glaciers and polar ice sheets, could raise sea levels 6 to 12 inches around Florida by 2030, and 9 to 23.6 inches by 2050. National Weather Service records already show an increase in the number of coastal flood events across the state over the past five years.

To learn what Florida is doing to prepare and protect, reporters with GateHouse Media newspapers talked with more than four dozen officials, planning experts and scientists.

A few local governments are all over the issue, chiefly in areas where rising water already has increased the number of times streets and yards are flooded by nuisance high tides or heavy downpours combined with high tides. That includes Punta Gorda, hit hard by Hurricane Charley in August 2004, and St. Augustine, where Hurricane Matthew caused massive flooding in October 2016.

Many other local governments are in various stages of learning about or planning for sea level rise. Some avoid the term, using words like resiliency and adaptation instead to describe preparations for rising seas and an increasing vulnerability to storm surge from tropical storms and hurricanes.

Others aren’t focused on sea level rise at all, despite data collected by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and others that shows seas are rising faster in Florida, as much as a third of an inch per year in South Florida over the past decade.

“Sea level rise is a different topic in and of itself and not one we are talking about locally,” said Jason Autrey, Okaloosa County Public Works Director. “It is not one we have programmed in at this time.”

As seas rise, so do efforts

In South Florida, rapidly rising seas have forced the city of Miami Beach and Miami-Dade County to spend hundreds of millions to raise roads, redesign storm water systems and strengthen their ability to hold back the water. Miami Beach experienced widespread flooding on Aug. 1, when a front associated with Tropical Storm Emily dumped 5 to 7 inches of rain within a couple of hours and a high tide prevented the rainfall from draining.

A study released this summer by a group of University of Florida researchers concluded sea levels rose nearly an inch a year between 2011 and 2015 along Florida’s east coast and the U.S. coast south of Cape Hatteras, North Carolina.

That’s six times faster than the long-term global rate, concluded UF researchers Arnoldo Valle-Levinson, Andrea Dutton and Jonathan B. Martin in a study published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters. They attributed the “hot spot” of sea level rise to the interaction of two large-scale climate patterns that often influence Florida’s weather — El Nino and the North Atlantic Oscillation.

El Nino occurs when surface waters along the equator in the Pacific Ocean off the coast of South America are warmer than normal. The North Atlantic Oscillation is a shifting pressure over the ocean credited with influencing how winds blow toward the coast, how much rain falls, and multi-decade periods of hurricane activity.

Similar pulses — with regional accelerations and then slowing in the rate of overall sea level rise — have taken place in the past, the researchers concluded.

Just as sea levels may be influenced by regional patterns in the ocean, sea level rise planning is being driven in part by regional planning councils in Southwest Florida, Tampa Bay, Northeast Florida and East Central Florida.

In Palm Coast, city officials worked with the regional planning council to assess the city’s vulnerable assets. They found one — a fire station — but at least six feet of sea level rise would be needed to compromise it, said Denise Bevan, city administration coordinator.

Credit the forward thinking of city and county officials, said Bevan and Flagler County Attorney Al Hadeed. Recognizing the community’s 26 miles of saltwater canals would be vulnerable to coastal flooding during hurricanes, the two governments set aside floodplain to reduce the risk along the canals. That put the city and county a step ahead in planning for rising seas.

In Sarasota, Stevie Freeman-Montes, the city’s sustainability manager, recently completed a vulnerability report on assets such as roads, sewage facilities and parks. Among the “priority assets” are two crucial causeways that connect the city to Lido Key and Longboat Key.

Now Freeman-Montes is looking at how those assets could be relocated or fortified, for example whether sewer lift stations could be outfitted with waterproof control panels. In the fall, she expects to begin looking at specific strategies for protection.

“It’s manageable,” she said of the preparations that may be required. “We just need to have the conversation.”

Not everyone’s planning

Like Okaloosa County, a broad group of governments aren’t having the conversations. Some are waiting for more research or are skeptical of the federal data and projections for sea level rise.

In Pensacola, the lack of discussion frustrates City Councilwoman Sherri Myers.

During her seven years on the council, Myers said she’s met probably 1,500 people from countries all over the world, many of them taking steps to combat sea level rise even though they might have far fewer resources than those available in this country. “It is really embarrassing that they come here and look at what we’re doing and our city is not even addressing it,” said Myers, who recently convinced her city to form a climate task force. “It makes us look backwards when we look like we’re not even having a discussion.”

Local governments that aren’t officially talking about sea level rise have plenty of company. For example, Wakulla, Dixie and Taylor counties, as well as the east coast cities of Edgewater, New Smyrna Beach and Flagler Beach aren’t talking about sea level rise.

Flagler Beach City Manager Larry Newsom attended a regional sea level rise workshop earlier this year and was interested in what he heard. But he thinks “more homework” is needed. It’s important to have accurate information, he said, before you start creating regulations that cost local businesses and industries more money.

Planning experts aren’t so sure about that.

“The biggest mistake we can make is to get mired in the uncertainty of how much seas are going to rise,” said Thomas Hawkins, policy and planning director for 1000 Friends of Florida, a nonpartisan nonprofit that advocates for growth management. “If we spend time quibbling about how bad the effects are going to be, it might prevent us from taking action.”

Pick an amount and plan for that, he said, embed it in building codes, plans for seawalls and building elevations. “The most significant thing Miami Beach did is to pick an estimate for sea level rise and plan for it,” he said. “If we want to be resilient to sea level rise, we need to be planning now.”

The state’s shifting role

Some believe Florida is already behind.

Conversations about sea level rise in Florida began in earnest in the late 1990s. That’s around the same time University of Florida researchers concluded a sabal palm forest in Cedar Key was dying as a result of the Gulf of Mexico pushing into underground water tables.

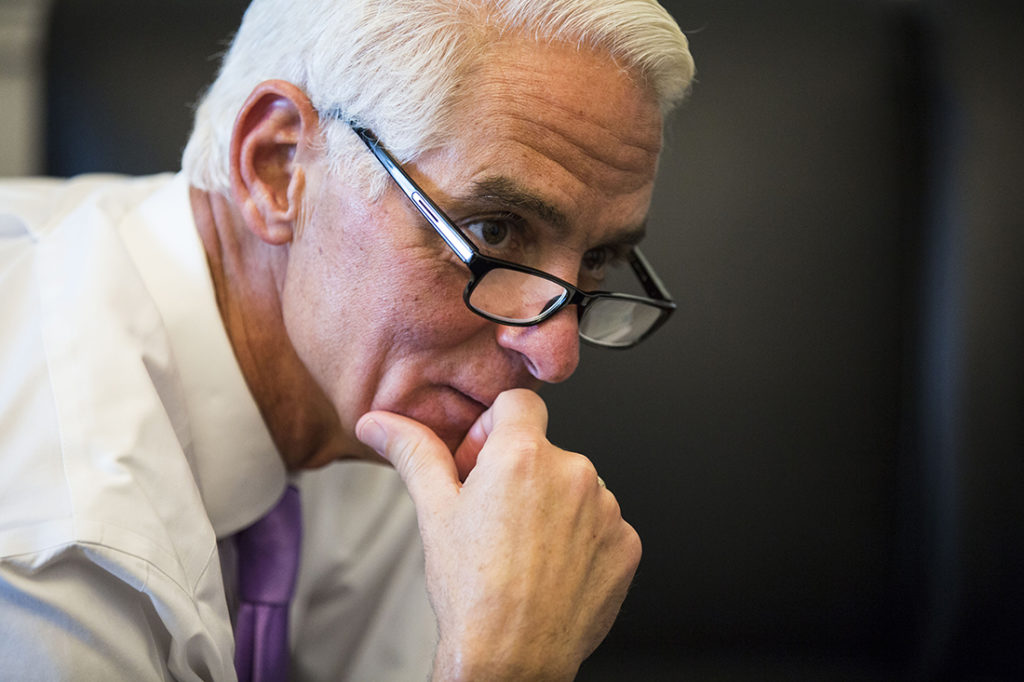

Ten years ago, Gov. Charlie Crist gathered government officials, businesses and nonprofits in Miami Beach. Crist stood next to then-California Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger — who implored the state to say “hasta la vista baby” to greenhouse gas emissions — and called for a statewide climate plan.

Florida should have been on the forefront, said Crist, now a St. Petersburg Democrat serving in Congress.

“We’re the state most susceptible to rising seas,” he said. “It all made sense to me, perfect sense.”

Crist organized another climate summit the following year, but then the Great Recession set in. In 2010, Gov. Rick Scott and a new administration took over in Tallahassee and the focus on sea level rise diminished.

“There was a lot of re-prioritizing,” said Jim Murley, chief resilience officer for Miami-Dade County and a former chief of the state Department of Community Affairs under Gov. Lawton Chiles.

However, Crist’s two climate summits had connected people, in Southeast Florida especially, where effects were already being felt. The region created a four-county working group in 2009, crafted a climate action plan, and now advises others on how to get started.

Today, the state’s planning efforts aren’t widely discussed and media reports indicate employees are discouraged from using the words sea level rise. For this story, the state Department of Economic Opportunity and the Department of Environmental Protection wouldn’t make anyone available for interviews about planning for sea level rise.

However, Dee Ann Miller, a DEP spokeswoman, provided a list of coastal resiliency planning and support efforts, including salinity monitoring and mapping. DEO offered its extensive website devoted to adaptation.

Both departments have provided assistance and money to local governments and regional planning councils, “regardless of the discussion about what words you use,” said Murley. “They were not pushing it forward in dramatic fashion, but it was technical work going on that was helpful to us.”

The DEP has funded most of the climate work by the East Central Florida Regional Planning Council, said Tara McCue, the council’s director of planning and community development.

Federal agencies, including NOAA and its Sea Grant Florida program, also have assisted in sea level rise planning efforts statewide with workshops and grant funds. Local officials are waiting to see how any changes to the federal budget might impact that work.

The federal government also has its own issues in Florida, where the Department of Defense has studied how its military bases could be impacted by rising seas. At Eglin Air Force Base, for example, NOAA estimates seas could rise as much as 68 inches by 2100. A 2016 study by the Union of Concerned Scientists, a national science advocacy group, deemed Eglin one of three Florida bases that could be at risk this century, with barrier islands on the southern end of the Eglin reservation exposed to daily tidal flooding.

Surge-prone Panhandle

The Panhandle, stretched along the northern Gulf of Mexico, has experienced devastating storm surge events throughout its history. With rising seas, those events could leave an even wider swath of damage.

Escambia County is beginning to assess its risks and potential impacts, said Tim Day, senior manager of the natural resources management department. The county is one of three governments, including the cities of Clearwater and St. Augustine, participating in a DEO pilot project to evaluate comprehensive planning measures for low-lying coastal areas experiencing coastal flooding due to extreme high tides and storm surge that are also vulnerable to rising sea levels.

The county can see the proof of rising seas on a NOAA tide gauge that has records dating back 92 years, said Day. “There’s very clear evidence here in Pensacola that the sea level has been increasing.”

And yet, as City Councilwoman Myers observed, planning for sea level rise isn’t a priority for Escambia County’s largest city, Pensacola.

However, the city is among several local governments where officials said their work to improve stormwater drainage and their community ratings with the federal flood insurance program will help defend against both storm surge and rising seas. Destin, Ormond Beach and Santa Rosa County also mentioned stormwater improvements.

Though Destin hasn’t formally discussed sea level rise, this fall the city plans to nearly double the size of Norriego Point, a finger of white sand that naturally protects Destin Harbor, home to Florida’s largest charter fishing fleet. The $11 million project, paid for with fines and penalties paid by BP after the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill, will armor the point and rebuild 1,150 linear feet, restoring it to its condition before Hurricane Opal in 1995.

Statewide, DEO is working with local governments to improve their ratings in the National Flood Insurance Program, which gives communities higher ratings for reducing their flood hazards. Better ratings mean bigger discounts for city residents who must buy flood insurance policies. Thirty-six local governments have a rating of 5 or better, which earns residents at least a 25 percent discount on flood insurance.

In Palm Coast, for example, the city benefits from its protection of about two-thirds of the 19,000 acres in the city’s special flood hazard area, said Bevan. That includes the Long Creek Nature Preserve, once zoned for condos. Preserving the land allows it to flood naturally when the water is high and then recede without flooding homes or businesses.

Across the state, the Florida Association of Counties walks a fine line on the politically sensitive topic of sea level rise, and informs interested member counties about measures underway in places like Miami Beach.

“We approach it from a policy standpoint and a reality standpoint, not a beliefs standpoint,” said spokeswoman Cragin Mosteller. “What we focus on are changes happening on our coastline.”

The Florida League of Cities, on the other hand, has taken a position and urges increases increasing efforts to adapt, said League spokesman Scott Dudley. Its 2017 legislative briefing states: “Florida is vulnerable to frequent and recurring flooding from tidal events and storm water. These events are increasing in frequency and threaten municipal infrastructure, public safety and the state’s tourism industry. In coastal and near-shore areas, seasonal high tides regularly flood downtown areas, sewer systems and canals, and have accelerated saltwater intrusion into drinking water supplies.”

‘Wasting precious time’

Scientists studying the impact of sea level rise — especially economic issues — call for more immediate action.

“Our pasts are no longer a good benchmark for what’s going to happen in the future, because the future is going to be a lot different,” said UF researcher Dutton, an assistant professor and fellow with the Florida Climate Institute who studies past sea level rise. If people will accept sea level rise as a reality, she said, “we can debate about the best way to deal with it. By not engaging in that debate, we are wasting precious time.”

Governments that delay action discount the long-term future risks, said Christopher de Bodisco, an environmental economist at Stetson University in DeLand. “There are statewide concerns that affect people, even if they’re not living on the coast.”

State and local governments will have to spend more money to repair and raise roads to replace drainage systems, said de Bodisco. And governments may be raising that money from a smaller tax base if property values fall along the coast.

The cost to address drainage and wastewater issues and other sea level rise-related issues are “billion-dollar, hundred-billion-dollar numbers,” said de Bodisco. The sooner governments “start recognizing those costs, the lower they’ll be and the more time we’ll have to spread those costs out.”

In January, the Tampa Bay Regional Planning Council released a report showing a 2.95-foot rise in seas potentially by 2060, which could mean the loss of $14.9 billion in residential properties in a six-county region, including Manatee County. The report, “The Co$t of Doing Nothing,” also found the region faces the potential loss of $1.3 billion in commercial properties and $5.4 billion in tax revenue.

In Manatee, Longboat Key and Anna Maria Island contribute about 15 percent of the county’s total taxes. David Bullock, Longboat Key town manager, said the “vexing future” of beachside communities could cast economic consequences on all of their neighbors.

Local governments already are fielding questions from financial institutions asking about long-term plans for resiliency, said Shaver, St. Augustine mayor and board member of the public/private nonprofit Resiliency Florida. “Obviously financial markets expect municipalities to be on top of this, to be doing the right kind of planning and identifying adaptation areas.”

That planning discussion needs to take place in a very deliberate way, she said. “The last thing that anybody wants or needs is to have some kind of real panic about this. We have a long horizon here, so let’s be very smart about it.”