Into the Light

Finding hope in a jail-first mental health system

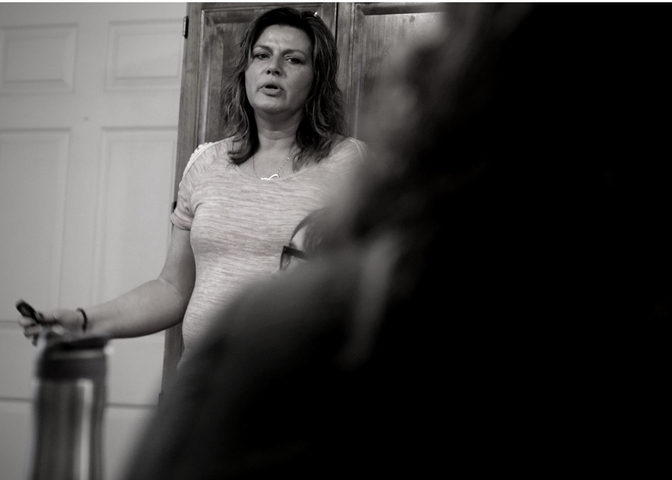

Photo by John Lovretta/GateHouse Iowa

Two years ago when Sherrie Benedict’s three girls and baby boy were put in foster care, she borrowed a loaded gun from a friend and sat down to write what she believed would be her last words.

The then 33-year-old single mom from Fairfield, saw no other choice. Her mental health was deteriorating and countless bouts in hospitals and jails hadn’t helped.

Her case was not unknown. In 2015, Benedict had been labeled one of the worst cases of borderline personality disorder that a local psychiatrist had ever seen. Psychiatric hospital staff all across southeast Iowa knew her name.

Suicidal thoughts had been with her since she was 14 years old. She couldn’t count how many times she had been taken to the hospital after attempting to take her own life. Her erratic and violent behavior had landed her in jails more than two dozen times.

Each time represented a chance for Benedict to start over. Still, recovery never seemed to be in reach. She went in and out of the state’s criminal justice and mental health systems, but Iowa’s traditional interventions failed.

“I just assumed my life was always going to be the way it was forever. I was doomed that way,” she said. “There’s no way to ever be anybody different. No way to ever be somebody better.”

Sixty years ago, a case like Benedict’s would have been handled very differently.

Institutions, which offered little to no freedom for those committed, were home to the severely mentally ill, but, beginning in the mid-1950s the country’s approach to mental illness dramatically changed.

Deinstitutionalization, led by the federal government, was the widespread reaction to growing reports of patient abuse and neglect, coupled with advances in psychiatric drugs. More and more people were also beginning to believe that the country’s approach to the mentally ill unconstitutionally limited the rights of people like Benedict.

As time passed, many believed the United States’ reformed mental health system, which replaced an emphasis on in-patient treatment with outpatient treatment, would work well, even for severe cases. They argued that outpatient treatment was better because it allowed people to stay in their communities with their own support systems.

Some found hope and began to share their story to inspire others — giving rise to the importance of peer support in the recovery effort. But many with chronic mental illness, decades of research now teaches, often suffered a different fate.

As states closed their public mental health institutions, officials didn’t create adequate outpatient community treatment to replace long-term hospitalization, experts said.

As a result, experts say, jails and prisons became the new asylums. The well-known chain of events followed: People going from jails to hospitals to the street, and then the cycle would repeat, said Michael Perlin, a leading disability rights expert and law professor at New York Law School.

Limited options, lack of government investment similar to funding for physical health systems, coupled with the demand for quick fixes rather than systemic change has led to a shuffling of people within systems that at times has deprived them of their constitutional right to treatment and in many cases exacerbated the problem, experts say.

“We believe that our current system fails miserably,” Perlin wrote in a recent report titled,“Who’s pretending to care for him?” “As long as that is the state of affairs, we are doomed to decades more of scholarship and case law — by law professors, judges, students and former presidents — appropriately decrying what has happened.”

In Iowa, there are about 132,000 people with a severe mental illness — double the population of a city the size of Ames — according to the statewide mental health advocacy group NAMI Iowa.

But there are only 760 staffed acute care beds statewide. Instead, many land in jail, advocates say. Nearly half of all inmates in county jails across Iowa have a mental illness, according to the advocacy group Disability Rights Iowa.

The Department of Corrections says nearly half of prison inmates also have a mental illness and found the likelihood of an inmate returning to prison after three years tripled if they’re diagnosed with a mental illness.

Children fare even worse. According to the National Center for Mental Health and Juvenile Justice, 70 percent of children in state and local juvenile justice systems have a mental illness. In Iowa, 4,513 children with disabilities are arrested per year, according to NAMI.

It’s unclear how many cases there are like Benedict’s as the state has only just now begun tracking those numbers.

Most efforts to improve Iowa’s mental health system over the last two decades have been piecemeal until 2012, when state lawmakers began to revamp the system: mandating the state’s 99 counties form regions, pool their resources and create services outlined in state code.

But the overhaul stopped short of helping adults with a serious mental illness transition into living successfully in the community. Another workgroup formed in 2014, but no substantive changes were made, the state later found.

Then, former Gov. Terry Branstad made two controversial decisions. First, he closed two of the state’s four public mental health institutes in 2015 without a plan to replace the beds. A year later, he farmed out the state’s Medicaid services to three managed care organizations, which has led to widespread complaints of delayed payments and canceled services, leading lawmakers to call for more oversight.

In December 2016, the Iowa Department of Human Services issued a new report that found most mental health providers across the state don’t have the ability to effectively treat people with severe “multiple complex needs,” which includes those with both a mental illness and a substance abuse disorder.

“These individuals are far too often admitted to inpatient psychiatric hospitals and, when they are ready to be discharged, have nowhere to go,” the report read.

This year, a statewide push from advocates, providers, lobbyists, families and those with a mental illness have called for the state to increase funding and fix the broken pipeline by offering effective treatment for more people like Benedict to rehabilitate their life.

“We live in a state where mental illness is criminalized and stigmatized,” a mental health coalition of nearly two dozen groups said in a letter drafted in October. “Simply adding more beds isn’t enough. We need a system overhaul. And we must work together to get there.”

Benedict’s earliest experiences were traumatic.

Her mother, addicted to street drugs, abandoned her and her siblings and left them with a relative. Benedict tells of how she would be beaten and locked in a room for days without food or water. She was also sexually abused as a child, she said.

To survive, the children pretended to be scouts on a survival mission.

Then, when she turned 11, she was placed in foster care along with her younger brother. It was in early adolescence that Benedict’s moods began to swing, violently. Her behavior only worsened as she was passed from home to home.

“Nobody understood that my being scared might have looked to them as someone full of hatred and anger and being a bully,” she said.

When real love was offered by a couple who was fostering her when she was 12, she had a difficult time accepting and trusting it. Her experiences had taught her to expect abandonment. And visits to a therapist didn’t help. After she was expelled from school, she found herself in a group home and then juvenile detention.

“Before I aged out foster care, I was told I wouldn’t amount to anybody. I was just going to be a future problem to the system,” she said. “I seriously believed I was nothing to society.”

Benedict would later prove everyone right. As an adult, she was arrested for disorderly conduct, domestic abuse, aggravated assault, and second-degree arson for lighting an abandoned Jeep on fire. Once when she was being taken to Des Moines County Jail, she told the arresting officer she would blow up the police station or set it on fire, police records show.

She was also the victim of repeated abuse, records show. Often when the police would arrive, her violent behavior would escalate.

Research shows officers who are untrained to understand mental illness often exacerbate the person in crisis with their traditional authoritative response. And coupled with Benedict’s fear of authority, she would lash out, charged more than seven times with assaulting police.

Years later, both Burlington and Fairfield police — where the majority of Benedict’s arrests took place — changed their approach to how they respond to those with a mental illness. Both departments sent officers to 40-hour crisis intervention training to learn how to de-escalate a crisis in a therapeutic way.

Often when Benedict was hospitalized, she fared no better. Forced to take medication and then released from the hospital, she would go on to overdose on what she was prescribed, her records show. In 2013, a University of Iowa doctor found she shouldn’t be on medication again because of a drug overdose Benedict said nearly killed her.

Mental health professionals often cite noncompliance as the No. 1 complaint when treating people with a severe mental illness, yet research suggests outcomes are better when patients and their families have a meaningful role in the planning and delivery of their treatment. But shared decision-making is controversial.

Opponents say people with a serious mental illness are often not capable of participating in decisions about their own treatment, but an initiative led by the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration found many were fully capable of making those decisions.

While living in Fairfield, Benedict met officers, attorneys and doctors, who she believed cared about her and tried to intervene, saving her life more than once, but it wasn’t until she met someone who could relate to her story and offered her autonomy that she began to change.

Benedict’s behavior baffled many, including herself, but it made sense to Joni Elder, a peer support specialist, who met the 33-year-old in 2016 when Benedict came to her office after writing her suicide note.

The rage and fear Elder saw in Benedict weren’t signs of defect. They were the symptoms of pain.

Abandonment, abuse and poverty had shaped Benedict’s brain, which was now wired with toxic coping mechanisms. Over the past few decades, a growing body of research has shown how adverse childhood experiences increase the risk of developing physical and mental illnesses.

Researchers at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have shown how the more trauma a child experiences the greater their risks as an adult of illness, domestic abuse, suicide attempts and early death.

Still, Elder, who had also spent time in the foster care system as a teenager, knew recovery was possible.

And a first step, she told Benedict, was understanding the effects of her past.

Psychiatry is still dominated by the medical model, which approaches a mental illness the same way as it does a broken leg, to diagnosis the problem and then fix it.

The model has often been criticized by those with a mental illness as deficit-oriented and physician-defined, ignoring intervention strategies that focus on what the person with the mental illness wants to work on, said Ken Duckworth, NAMI’s medical director.

But the recovery model speaks to individual goals. It approaches treatment from a place to help people reclaim their life and live in a meaningful way. But its goals can often be hard to measure and in a world of shrinking resources, if a program can’t be measured it often doesn’t receive adequate funding, Duckworth said.

Yale Program for Recovery and Community Health, which is shaping how communities approach recovery-oriented care, defines this type of care as patients and their loved ones having a primary role in all health aspects. There is swift and uncomplicated access to care, individual treatment plans that respect the individual’s rights, while interventions are aimed at assisting people in gaining autonomy, power and connection with others.

Twenty years ago, Iowa was on the cutting edge of a recovery-oriented model when the state and the mental health provider ResCare partnered with the University of Boston, which developed the psychiatric rehabilitation approach.

The program was catered to help those with a severe mental illness recover through an intense skills-based approach called Intensive Psychiatric Rehabilitation, said Tim Bedford, a national trainer with Boston University and executive director of Central Iowa Recovery.

While Iowa was only the second state in the country to adopt the approach — shown to improve people’s housing conditions and quality of life and is now used worldwide — the grant for the pilot program eventually was discontinued. However, the state does continue to reimburse for those on Medicaid, DHS spokesman Matt Highland said.

On his own, Bedford helped expand the Boston approach at several companies, and in 2012, he partnered with multiple central Iowa counties to help form Central Iowa Recovery to offer intervention classes across a 15-county region. He continues to train other providers across the state, but the approach isn’t widespread, he said, in part, due to the steep training costs.

Elder, the Optimae peer-support specialist working with Benedict, incorporates the rehabilitation principles into her approach. But when she met Benedict, she didn’t think she was ready for a change.

But Benedict was intrigued. Elder had probed her with questions about her life goals and how she found her happiness — questions she didn’t know how to answer. But Benedict wanted to learn more.

While therapists and doctors had tried to tell Benedict she had borderline personality disorder, Elder realized she had no context for her diagnosis, so instead, she showed Benedict a video clip of a woman with the same diagnosis describing her symptoms.

“That’s me,” Benedict said at the end of the video.

Still, Benedict tried to quit the program four times. But since Benedict made the commitment, Elder held her accountable. Once when Benedict missed her session and ignored Elder’s calls, Elder barged through her front door and handed her a note that read, “You can not get back on your feet until you first get up off your ass.” The note still hangs on her refrigerator.

For the next six months, Benedict met with Elder every week.

When Benedict began to gain more self-awareness and learn tools to cope with her stress, Elder asked her to make a list of her goals in life. Setting goals revealed her core values in life, which helped Benedict realize where she had made mistakes.

She began to see how she had been drawn to toxic people and situations and needed to cut them out of her life if she wanted to get well.

Then when Benedict was ready, Elder asked her to join her group class to learn practical tools to regain control of her life and to share common ground with her peers.

The recovery-oriented approach to mental healthcare has other applications that some say could revolutionize mental health care in Iowa.

One example is creating short-term housing with around-the-clock professional care. Another is the expansion of response teams known as Assertive Community Treatment teams.

ACT teams, comprised of professionals who provide a more intense form of case management that is individualized and around-the-clock, are one of the most widely used rehabilitation programs across the country. They go to the person in crisis and connect them with resources where they can learn the skills to live independently.

These are approaches a state work group recommended to the Legislature that were adopted in newly passed legislation Gov. Kim Reynolds signed March 29.

But the mental health regions will have to find a way to fund the steep start-up costs for these programs because the state didn’t appropriate any new funding.

“Until they find another way of funding those services those services are a pipe dream,” said Teresa Bomhoff, NAMI Greater Des Moines president.

This summer, a bipartisan committee plans to meet to discuss new funding streams.

Another criticism is that there are too few professionals, and a focus on new programs could jeopardize the state’s already existing case management program, known as Integrated Health Homes, that currently oversees 24,000 Iowans with chronic mental health problems. This recovery-based program is already under review by the state after the managed care organization UnitedHealthcare abruptly tried to stop funding the service in December, creating an uproar from families and state lawmakers.

Still, if regions are able to create the newly mandated crisis services, options remain limited for people with a mental illness who are already caught in the state’s criminal justice system.

Across Iowa, there are only four mental health courts — intervention that experts say is a proven approach to divert people out of the criminal justice system, offering a lifeline.

“There is no question that one of the most important developments in the past two decades in the way that criminal defendants with mental disabilities are treated in the criminal process has been the creation and the expansion of mental health courts,” wrote Michael Perlin, the New York Law School professor. “These courts, providing, as they do, ‘nuanced’ approaches, and may signal a fundamental shift in the criminal justice system.”

But the Iowa Judicial Branch currently has a moratorium on creating new speciality courts, citing a $15 million budget deficit. And department spokesman Steve Davis said officials will decide whether to phase out those remaining courts in the 2019 fiscal year if their budget isn’t restored.

Another important link between the criminal justice system and the mental health system, research shows, is equipping county jails with properly trained employees, screening for mental illness, offering psychiatric rehabilitation programs, and coordinating services to help people transition back into the community after they are released.

In 2016, Disability Rights Iowa investigated county jails and found many lacked proper training of staff. It also found cases of use of force and isolation of inmates with a mental illness and that jails had abruptly stopped a person’s medication.

A new state ombudsman report detailed how complaints against the Department of Corrections rose 24 percent, while complaints against county jails went up 34 percent from 2016 to 2017.

State and local correctional officers blamed the discontent on the growing population of the mentally ill, who they said were unwilling or unable to abide by the rules, the report said.

By late 2017, the majority of county jails had begun to offer jail diversion services that link inmates with a mental illness to community programs, a state report found.

Those services vary across the state, but in Story County, officials have taken a proactive approach to bring rehabilitation services to the jail.

Recently, the jail, which already offers health assessments, therapy, and jail diversion, expanded its services, partnering with Central Recovery Iowa to include intensive psychiatric rehabilitation.

Twice a week, facilitator Heather Spaulding holds a three-hour class along with access to one-on-one meetings to teach inmates the skills to recognize how they can successfully live on their own. The goal is to seamlessly add them to one of Spaulding’s classes in the community after they are released, she said.

“Jail is a really good place for rehabilitation,” Spaulding said. “People realize, ‘I need to get help’ to get out of rock bottom. A lot of them are saying, ‘I have a mom or an old girlfriend and that’s the only support I have.’ … This program creates community support.”

Nearly two years to the day after Benedict met Elder, Elder invited her to share her story at a conference at Indian Hills Community College in Ottumwa.

Elder had been asked to share a PowerPoint presentation showing the need for more recovery-based programs across the state with more people trained in rehabilitation strategies to help people like Benedict.

Across the state, there are about 40 intensive psychiatric rehabilitation practitioners, and Elder said she only knows of a handful of people who are also trained to teach the Wellness and Recovery Action Plan, another evidence-based recovery approach she’s adopted.

Peer support specialists, who are one of the bedrocks of recovery, also vary across the state, said Diane Funk, the director of the University of Iowa’s Peer Support Specialist Training Program. Many in peer support function more in a case-management role with high caseloads and don’t have time or the funding to meet with people one-on-one like Elder does.

Sadly, most people don’t know of anyone they could reach out to in a crisis, Elder said, citing a recent study.

But Elder didn’t linger too long on the facts, giving Benedict plenty of time to speak.

The women had celebrated many victories over the last two years. After six months in Elder’s class, Benedict has been able to get her children back. She also wrote letters to officers apologizing for how she had treated them and once when police confronted her, she apologized and smoothed over the tense situation without getting arrested.

Elder had also helped Benedict through her setbacks. When Benedict was arrested in October after a confrontation with police, she was able to help her trace where she had ignored the warning signs leading to her breakdown and to remind her that recovery wasn’t linear — that every time she fell down she had to get up and work at it again.

Along the way, Benedict developed the tools to help her control her moods and behavior without medication. She told the crowd how she had discovered happiness.

“In this program, I learned so much more because I wasn’t forced to do it,” Benedict said. “I could do it on my own time. Nobody criticized me. Nobody judged me.”

Now, she told them, she was pinching pennies to be able to attend the training to become a peer support specialist and teach others what she has learned.

“All I hope, that one day when my story goes far is that somewhere it will put hope into somebody,” she said, “That is my main goal.”

After all, in her own life, when she found someone else with hope, she finally discovered it for herself.

Web production: Caitlin Ware

Graphic and audio production: Dan Mika