State of Health Care in Kansas

Your life. Your wellness. Join us on an in-depth exploration of health care in the Sunflower State, with a collection of more than 20 stories.

Innovative recruiting in southwest Kansas offers hope amid doctor shortage; commitment to community also part of cure, southwest Kansas administrator says

Small-town hospital administrator Benjamin Anderson's introduction to the physician shortage in Kearny County was painful.

He was told in 2013 when hired to manage the county hospital in southwest Kansas that the facility was in the market to hire five doctors and was about to lose one of four physicians on staff. The remedy formulated in the tiny hospital in Lakin, a city of 2,200 people marked by economic pendulums of the agriculture and energy industries, is now being replicated to address the shortage of primary care doctors infecting Kansas and other states.

The answer at Kearny County Hospital to the uneven distribution of health care providers necessitated a culture shift at the hospital, Anderson said. Every physician had to be a full-spectrum provider in terms of working in the emergency room, delivering babies and sharing the on-call duties equally. The role of physician assistants and nurse practitioners was amplified. Staff salaries were brought in line with industry rates.

In an unorthodox move, Anderson began recruiting doctors completing professional residency programs by offering contracts with an eight-to-10-week window each year for overseas humanitarian work. The quest was to entice people wired to serve in medically challenged countries, which often aligned new doctors with the constellation of refugees and immigrants moving to western Kansas.

"We agreed the millennial generation was full of mission-driven people. When they work with purpose, they are very, very engaged," he said.

Anderson said the recruiting-and-retention campaign blossomed into another project to fly job candidates to western Kansas for a personal introduction to communities seeking their expertise.

Kearny County Hospital filled its physician vacancies in about one year and draws about 20,000 patients annually from more than a dozen counties. That's double the patient volume of six years ago.

Surveys and studies have documented the decades-old problem with placement of primary care physicians in Kansas. Health professionals, not just primary care physicians, persist in gravitating to jobs in urban locales, which they believe provide solid career opportunities and a quality of life for their families.

United Health Foundation, through America’s Health Rankings, ranked Kansas as the 27th healthiest state in 2018. Colorado was eighth, while Missouri was 38th. In terms of primary care doctors for every 100,000 residents, Kansas ranked 31st in the nation for the third consecutive year. That headcount included doctors in general practice, family practice, obstetrics and gynecology, pediatrics, geriatrics and internal medicine.

"Like many states, Kansas is facing a physician shortage," said Michael Kennedy, associate dean of rural health education at The University of Kansas Medical Center in Kansas City, Kan. "What makes the situation acute is that there is an uneven distribution of physicians, which leaves underserved areas with critical shortages."

By the numbers

The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation ran numbers based on 2015 data that offered insight into the range of coverage by primary care physicians from county to county in Kansas. The population-to-doctor ratio in Kansas averaged 1,320 residents for every doctor. Nationally, the 90th percentile benchmark was 1,030:1.

Here is a sampling of the diversity in patient-to-doctor coverage among counties in Kansas: Johnson County, 830:1; Brown County, 890:1; Sedgwick County, 1,150:1; Douglas County, 1,180:1; Saline County, 1,270:1; Shawnee County, 1,390:1; Ellis County 1,610:1; Finney County, 1,860:1; Ford County, 2,030:1; Wyandotte County, 2,550:1; Kingman County, 7,690:1; and Linn County, 9,540:1.

More than two dozen Kansas counties have been declared frontier areas in medical terms, because there are two or fewer primary care doctors in each.

The three medical schools in Kansas are affiliated with The University of Kansas and operate on branch campuses in Wichita and Salina, as well as the original complex in Kansas City, Kan.

The Salina campus, founded in 2011, was conceived with the understanding it would focus on addressing the ever-growing need for primary care doctors in rural areas. With eight students per class, KU Medical Center officials said the Salina campus was suited for self-starters who could be a better fit at health facilities in rural communities, where resources may differ from larger hospitals or clinics.

The Wichita campus was born in 1971 out of the need for hands-on clinical training for students in their final two years of medical school. It grew to become an integral part of the training of primary care physicians practicing throughout the state. The Wichita program, which expanded to four years in 2011, is a community-based enterprise with more than 1,000 volunteer faculty located at three partner hospitals. As a result, KUMC said, students benefit from exposure to a wide variety of clinical experiences, especially family medicine.

The American Association of Medical Colleges ranked the KU School of Medicine in the 96th percentile in producing doctors working in rural settings 10 years to 15 years after graduation.

Garold Minns, dean of KU School of Medicine-Wichita, said the ranking meant the university's graduates were working with underserved populations from the urban core in Kansas City, Kan., to sparsely populated areas along the Colorado border. However, he said, more should be done to deal with the shortfall of primary care doctors. The gaps can be geographic, given the distances between clinics and patients, or demographic, resulting from a concentration of low-income residents.

"We need more primary care physicians in Kansas. Primary care physicians are the foundation of medical care systems," he said.

Tom Bell, executive director of the Kansas Hospital Association, said academic scholarships and college loan repayment programs had produced more medical school graduates in Kansas. There remains a shortage of post-graduate training residency opportunities across the state, he said.

"We are graduating physicians," Bell said. "We really could use more residency slots. That would go a long way."

Welcoming new doctors

Anderson, who began developing his novel approach to doctor recruitment while working for a hospital in Ashland, said the key to retention of medical professionals in underserved regions involved development of a sense of community sought by new arrivals. The loneliness felt by a Texas-trained doctor living in Lakin resembles the separation experienced by immigrants to Kansas, Anderson said.

The ongoing work, he said, was to demonstrate that a cure to doctor shortages required building upon an educational foundation with professional opportunities and a commitment to community.

Anderson said one of the most important duties he and his wife performed recently was serving as babysitter for a 2-year-old child so a physician and his wife could go on a date. On a recent evening, Anderson and some of his immigrant friends hosted a gathering for prospective hires.

"We have the answers," Anderson said. "Raising two fingers off a steering wheel is not hospitality. The question is: Will we share our dinner tables?"

He said rural Kansans are among America's best-kept secrets. If they let newcomers into the circle of trust, he said, people find hardworking, honest, faith-driven people who can form "friendships for life."

About 18 months ago, Anderson was in Texas to help recruit a physician to the Kansas community of Tribune. He asked a group of residents — doctors finishing their training and ready for the marketplace — if they would be willing to visit southwest Kansas if flown there by charter.

Eventually, 20 agreed to explore Kansas. That initial group had a steak dinner in Garden City. Gov. Jeff Colyer, a surgeon, spoke to the group. Some of the recruits signed contracts to work in Kansas.

The fourth such recruiting flight bringing health professional prospects to Kansas is scheduled for Feb. 1.

Interest is high enough that job applicants have been referred to other Kansas hospitals with management that subscribes to the recruitment framework piloted at Kearny County Hospital.

Anderson, raised on the West Coast and educated on the East Coast, said the hospital in Lakin had proven quality prospects were hungry for careers in locations that offered professionally and culturally safe environments for constructing a medical career and raising a family. While doctors and nurses audition for jobs in Kansas, he said, so must residents of communities in demand for those medical services.

"There are more mission-driven, well-trained millennial family physicians interested in practicing in rural Kansas than there are safe places to hire them," Anderson said.

He said he believes a reasonable 10-year goal should be: One primary care physician within a 30-minute drive of every Kansan.

Kansas health professionals address opioid crisis; report says more than 1,500 Kansans have died from overdoses since 2012

The battle over the nationwide opioid crisis is a matter of life and death for Jim Wolfe.

The 60-year-old Canton man lost his job as a welder, his wife of 30 years kicked him out, and an overdose in June nearly cost him his life.

"I had a good life, but the opiates snuck in and attacked me, and I guess I chose to do nothing about it," Wolfe said. "I became everything I despised."

His longtime struggle with addiction started with drinking at age 18 and meth at 28. He got clean and spent a decade sober before knee surgery set off a downward spiral from Percocet to heroin and crystal meth.

"I didn't think I had a problem with pills until I got hooked on it, and it's just been a battle," Wolfe said. "Opiate withdrawal sucks. It's painful. You're sick. You've got diarrhea. It's miserable. It's one of those things where you'd sooner use than be sick."

Wolfe's brush with death landed him in the hospital for a week, followed by a stay at an inpatient treatment facility in Dodge City and on to outpatient services at CKF Addiction Treatment. Clean for six months, Wolfe receives treatment, including counseling and the medication Suboxone, from a grant through the Department of Health and Human Services' Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Today, Wolfe is engaged to be married, has a relationship with his two adult daughters and four grandchildren, and helps others with their treatment at CKF Addiction Treatment.

"I don't even think about opiates. I don't hurt like I used to," he said.

Public health emergency

More than 1,500 Kansans have died from opioid or heroin overdoses since 2012, according to the Governor's Substance Use Disorder Task Force, which released a report in September. Drug poisoning killed more than 300 Kansans in 2016 alone, and prescription drugs were involved in 80 percent of drug poisonings from 2012 to 2016. Nationwide, opioid-involved overdoses killed 42,249 people in 2016, according to the Kansas Prescription Drug and Opioid Misuse and Overdose Strategic Plan released in July.

A number of factors contributed to the rise of opioids, starting with a focus on eliminating pain, according to Greg Lakin, chief medical officer for the Kansas Department of Health and Environment and chair of the Governor's Substance Use Disorder Task Force. The medical community also was led to believe that opioids weren't addictive by pharmaceutical companies that aggressively marketed the drugs, he said.

In 2016, the CDC issued guidelines for prescribing opioids for chronic pain that aimed to reduce the risk of opioid use disorder. In 2017, the Trump administration declared a nationwide public health emergency regarding the opioid crisis.

While Kansas hasn't seen the extent of problems that other states have, "We've still been hit hard. It truly is a crisis," Lakin said.

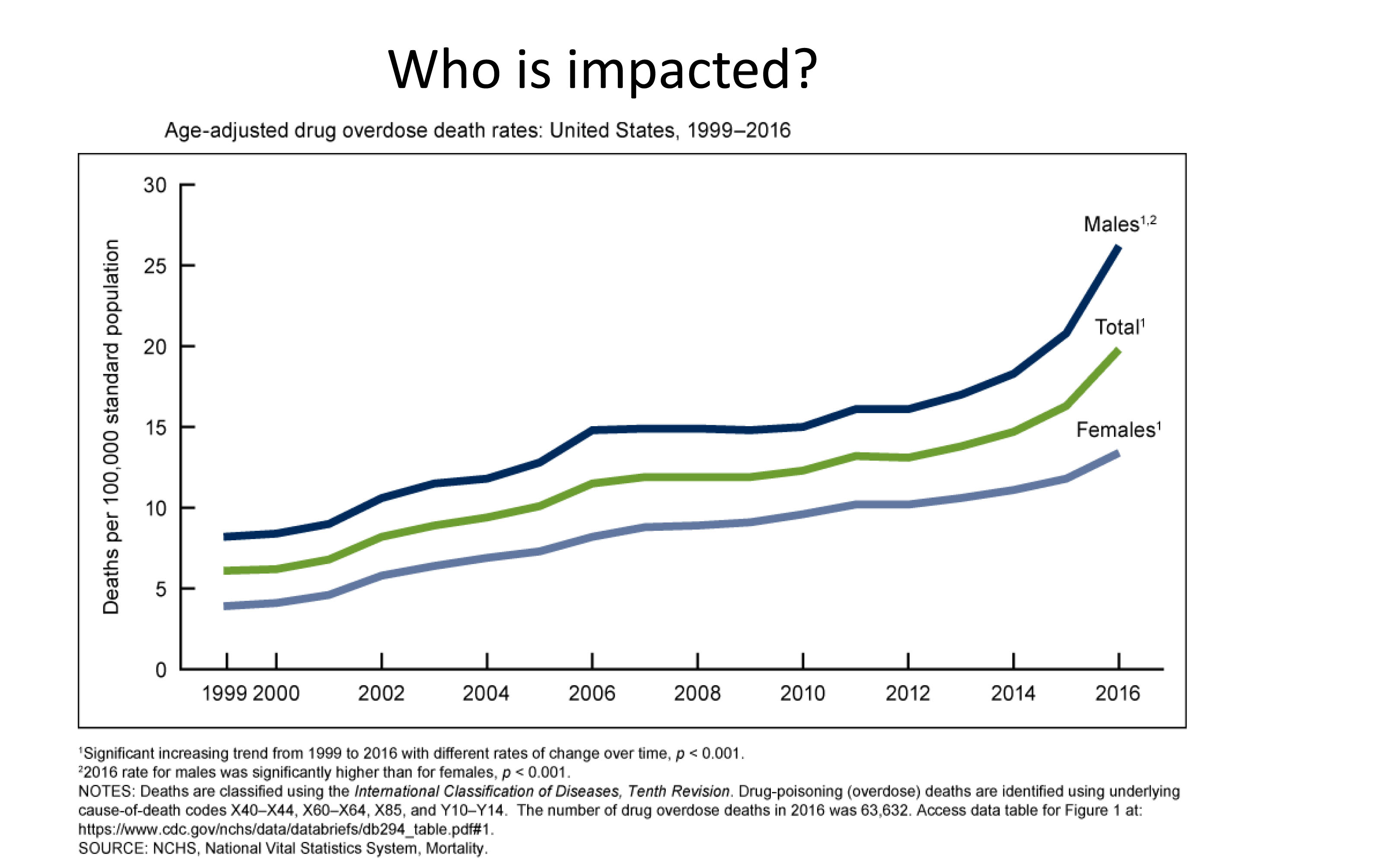

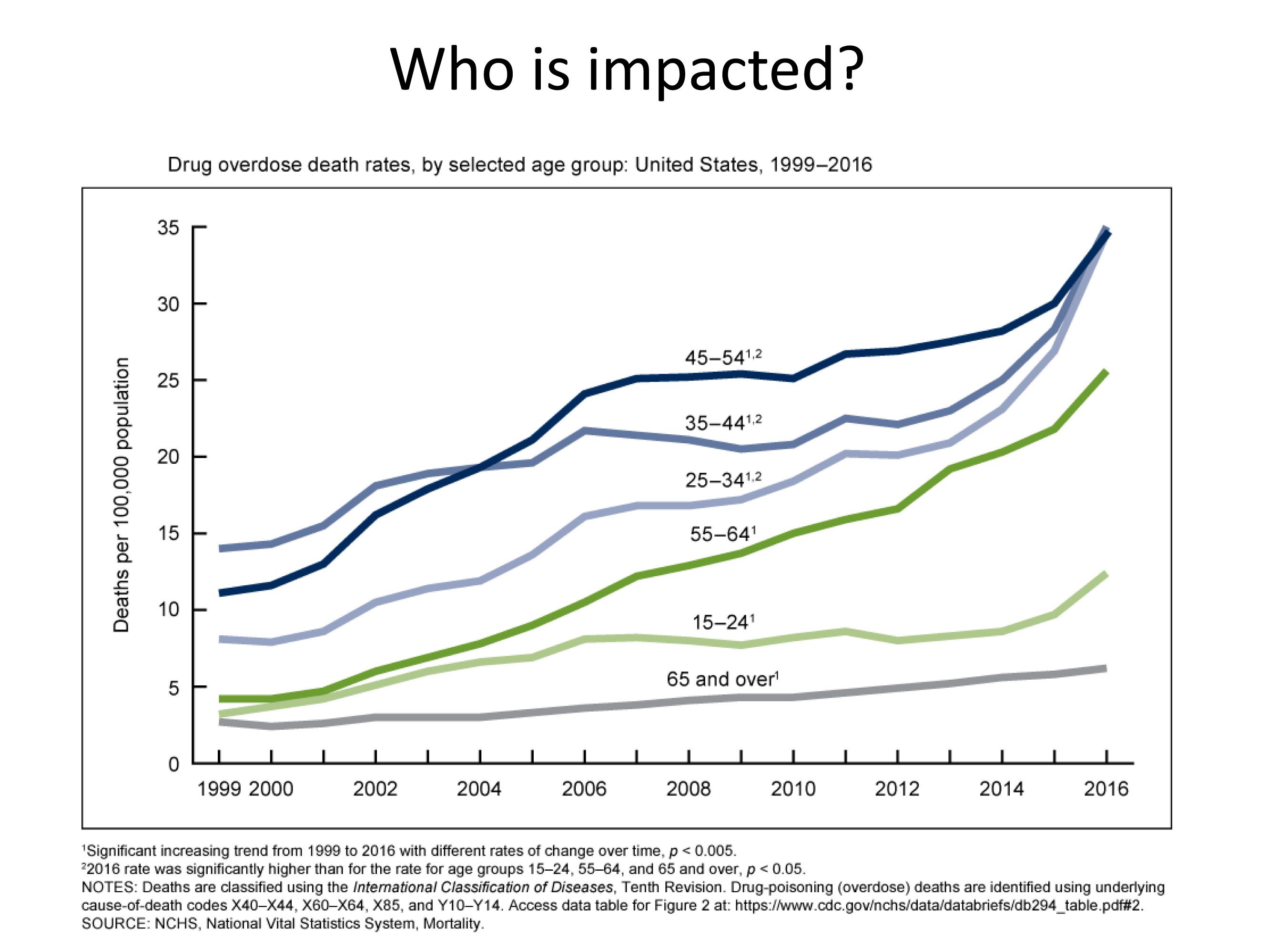

As far who is affected, "It's not who you think," Lakin said, pointing out that many who struggle with opioids are middle-aged professionals.

"Oftentimes these are very good people, but they're having to steal, they've having to burglarize, they're having to take money out of their mother's purse, they're having to do things they would never have done," he said.

While attention is on prescription drugs, many overdoses can be traced to illegal drugs, such as heroin laced with fentanyl that makes its way here from China, Lakin said.

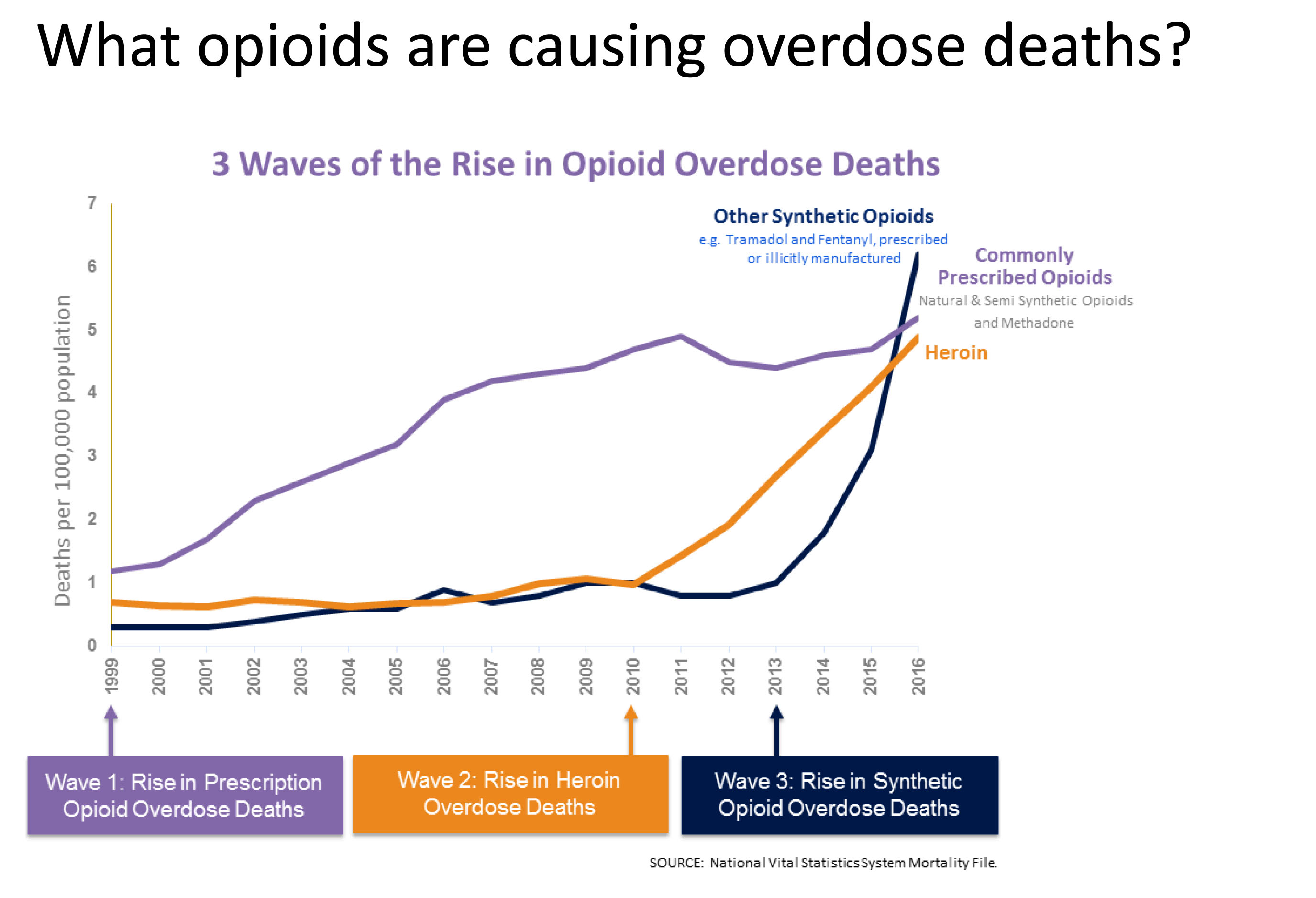

The opioid crisis has evolved in three waves, said Karan Braman, senior vice president of the Kansas Hospital Association and a member of the task force. The first wave, starting in the 1990s, was prescription opioids, driven by overmarketing of OxyContin, she said. That was followed by a wave of heroin overdoses after Mexican drug cartels targeted areas where OxyContin was being abused. The third wave is fentanyl addiction.

"I think everything we're doing for opioids — because that's where the attention and the money is — is certainly going to help with treating other substances as well," Lakin said.

Seeking solutions

The state has received about $30 million in federal grant funding, which has supported prevention, awareness, education and treatment to combat the opioid crisis. But funding, which comes in "somewhat haphazardly," has been a source of frustration for treatment providers, Lakin said.

The Governor's Task Force made 34 recommendations in five focus areas: provider education, prevention, treatment and recovery, law enforcement, and Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome. Recommendations include establishing permanent funding sources for various programs, increasing awareness and use of the state's prescription drug monitoring program, expanding medication-assisted treatment and promoting the use of naloxone, an overdose antidote.

Lakin signed a standing prescription allowing anyone in the state to go into a pharmacy and get naloxone. Now he is working to spread awareness about the potentially lifesaving drug, which is marketed as Narcan, hoping to get it in the hands of more police and emergency medical service workers, along with friends and family members of those with the potential to be at risk of overdose.

"It's just a safe way to save lives," he said, noting that the nasal spray is harmless if administered unnecessarily.

"I have had many patients that had a wake-up call to their addiction, realized they were on the brink of death … realized it was time to get treatment," Lakin said.

Local efforts

Work to address the opioid crisis on the local level has included efforts to reduce opioid doses and prescriptions, use alternatives for managing pain and assess patients' ability to function rather than use a traditional pain scale.

"Every community is different, and solutions that work the best are local solutions," said Braman, with the Kansas Hospital Association.

Labette Health in Parsons has been a leader in combating the opioid crisis, receiving national attention for its efforts to improve patient safety and participating in national presentations to share success stories with other hospitals.

In 2014, the organization set out to reduce adverse drug events, with a goal of cutting the number of naloxone administrations for patients receiving opioids within the hospital by 40 percent by September 2016, said Tereasa DeMeritt, director or quality.

The organization took a multimodal approach that involved peri-operative, pharmacy, orthopedic and frontline staff. Some measures that were adopted included giving smaller doses of opioids incrementally and using alternatives to opioids, such as regional blocks, IV acetaminophen and gabapentin.

Labette Health surpassed its goal, reducing naloxone administration by 73.2 percent, reducing opioid administration by 44 percent and increasing its pain management scores to the 90th percentile, DeMeritt said.

"Overall, we did not make significant system changes," she said. "We made small, incremental changes that made a significant impact. Being transparent with our data and sharing it to educate and engage our team was key."

Prescription monitoring

One of the state's most successful tools in fighting the opioid crisis has been the prescription drug monitoring system K-TRACS. Established in 2010, K-TRACS alerts prescribers and pharmacists when patients reach a threshold of getting at least five controlled substance prescriptions from prescribers and visiting at least five pharmacies to fill those prescriptions in a 90-day period.

Lori Haskett, assistant director of the Kansas Board of Pharmacy, pointed out one such patient who received 15 controlled substance prescriptions from 14 different prescribers, which were filled at 15 different pharmacies in Kansas and noted that grant-funded enhancements to K-TRACS have helped significantly curb such suspicious patient behavior.

The number of threshold patients dropped from a high of 300 in September 2013 to 118 in December 2017, according to the Kansas Board of Pharmacy.

The Kansas Board of Pharmacy and KDHE are partnering on a CDC grant-funded effort to integrate K-TRACS into health care providers' electronic medical records. Integration saves an average of four minutes per patient because providers don't have to log in to separate systems. Thirty hospitals and 127 pharmacies are integrated.

Eric Voth, vice president of primary care at Stormont Vail Health, said combating the opioid crisis requires a balance between conflicting demands. On one hand, there are those who have a legitimate need for opioids. But the consequences can be severe when the drugs are misused.

Stormont Vail is participating in a national research project with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to study the effect of using electronic medical records to track opioid prescriptions.

The organization has integrated K-TRACS into its electronic medical record, allowing health care providers to easily access a patient's prescription history. Stormont Vail also screens patients with detailed questions, administers drug tests and obtains informed consent agreements before prescribing opioids.

"You can't just withhold opiates," Voth said, "but by the same token, if there looks to be a clear pattern of drug abuse, it's really not wise to put the opiates in on top of it."

The problem is far more complex than careless doctors overprescribing opioids, Voth said, cautioning against overreactions that might vilify physicians or lead to changes that might somehow harm providers.

"There are some providers that are looser than others, no doubt, and there's been a lot of marketing, of course, but I've always sensed that the providers I've been around have been really careful and are trying to do what's best for patients," he said.

Treatment

The opioid crisis requires a holistic approach to solving it, one that considers policies, funding, education, social factors and traumatic childhood experiences, with three major steps: diminishing supply of opioids, diminishing demand and saving lives, said Gianfranco Pezzino, senior fellow and strategy team leader at the Kansas Health Institute.

"There is really no doubt at this point that it is a brain disease and needs to be treated as such. It's not the result of poor personal choices," he said.

Braman, with the Kansas Hospital Association, emphasized the need to increase access to addiction treatment services.

"Addiction is a disease. It's not a moral failing," she said.

Based in Salina, CKF Addiction Treatment treats about 2,000 Kansans a year at its outpatient treatment facilities in Salina, McPherson, Abilene and Junction City and sees an additional 5,500 through a screening program at Stormont Vail and Salina Regional hospitals. Treatment includes doctors' appointments, counseling and medication, and the CDC grant covers all of it for qualifying low-income Kansans. Lindsey Ray and Shilo Redger are two such Kansans receiving treatment through CKF Addiction Treatment.

Ray had been addicted to opioids for about 10 years, having gotten hooked after receiving treatment for chronic back pain. A longtime addict who was introduced to cocaine by her father at age 14, Ray had tried to quit using drugs many times when she sought help after the birth of her fourth child in 2013.

"After she was born, I realized I didn't want to live like this anymore," the 33-year-old Stockton woman said. "I didn't know there was a way out. I didn't think I was ever going to get better."

She said she used drugs throughout her pregnancy and lucked out that her baby didn't suffer any withdrawals.

"It's not something I'm proud of, but it's part of my story," she said.

In October 2014, she started taking Suboxone, which combines an opioid and opioid blocker. She said she was doing well with her recovery until relapsing after she missed an appointment and stopped taking the medicine. She is back in recovery and has been taking Suboxone for about a year.

"For me it's a miracle drug. It has enabled me to live a normal life and be a good mother to my children and be a good wife," said Ray, whose children are now ages 17, 15, 9 and 4.

Medication-assisted treatment is controversial, with critics saying it amounts to replacing one drug with another. Ray said two of her siblings, who also have struggled with addiction, were skeptical. Since seeing her get sober, they have started treatment, she said.

Shane Hudson, CEO of CKF Addiction Treatment, said that while patients on Suboxone are physically dependent on the medicine, it allows them to move past the chaos and negative effects of addiction and find balance and stability in their lives.

"I'm not using it to get high," Ray said. "I want to feel normal, and people don't understand that. I had already done so much damage to my brain from being an opioid addict."

Opioid addiction also ran through Shilo Redger's family, including her grandparents, parents, aunt and uncles. The 29-year-old Plains woman said she began struggling with opioid addiction in her teens after a surgery and has been in and out of treatment. She also has struggled with addiction to meth.

Redger said traumatic experiences contribute to addiction, and she's had her share, including a series of health concerns, the sudden death of her fiancé of carbon monoxide poisoning, and losing and regaining custody of her two sons, ages 10 and 7.

She has little trust in doctors, who she says "were handing (opioids) out like candy." Redger credits Suboxone with saving her life, but she said she hopes to get off the medicine eventually.

"I do not like the fact that I am still feeding into this monster of pharmaceutical companies," Redger said. "It's ridiculous. They've got their hand in the pocket of each and every American in this country."

She points to two needs that she sees as downfalls of addiction and keys to recovery: a spiritual connection with God or a higher power, and strong social connections, particularly with family.

"Nobody wants to talk about addiction. Everybody has it, but nobody wants to talk about it. Nobody wants to deal with it," Redger said. "Almost every family that I know of has been affected by these drugs in some way, shape or form."

Jonna Lorenz is a freelance writer. She can be reached at jonnalorenz@gmail.com.

How do I feel today? Social-emotional learning teaches youths how to manage emotions

Each morning, students at Salina's Heusner Elementary School pick a "zone" on which they attach a clothespin bearing their name.

If the student attaches their clothespin to the green zone, it means they feel happy, calm, focused and ready to learn. The yellow zone indicates frustration, worry or feeling some loss of control. The blue zone reflects sadness, sickness, tiredness or boredom, while the red zone means the student is feeling angry, mean, terrified or out of control.

Each morning, individual teachers call "morning meetings," where the kids greet each other, talk about how they feel that day and perform a group team-building activity before starting the day's lessons.

"The morning meeting is all about community building and establishing a relationship between the staff and the kids," said Julie Clayson, a family support worker at Huesner. "By talking about what 'zone' they're in, it gives children the ability to talk about emotions, that it's not bad to feel sad or mad because they can get the emotional support they need and learn coping skills."

If a child is feeling angry or out of control, they might go to a "peace zone," a designated area in classrooms where the fluorescent lights are muted, and they can relax and relieve their stress through therapy putty, a stress ball, sensory bottles or a Hoberman sphere.

"When it comes to behavioral issues, early intervention makes a big difference," said Lori Munsell, principal of Heusner Elementary School.

Early intervention is the goal of social-emotional learning, one of the talking points of KansansCan, a vision for education spearheaded by the Kansas State Board of Education in Topeka. Social-emotional learning is the process through which students acquire the knowledge, attitudes and skills necessary to understand and manage emotions, set and achieve positive goals, feel and show empathy for others, establish and maintain positive relationships, and make responsible decisions.

Integrated approach

KSDE is collaborating with the University of Kansas to provide implementation of a statewide, integrated tiered approach for social-emotional support.

"It's become a renewed focus for the state of Kansas," said Shanna Rector, executive director of administration and student support services for Unified School District 305 in Salina. "It's a lot more than focusing on students with trauma. We want to make sure all students have the skills they need to be successful, productive citizens. It's about giving students a skill set they can use whenever problems come their way, whether perceived or real."

Programs being explored to integrate into classes, beginning in elementary school, include focusing on developing students' core values and their applications to everyday life decisions; connecting service in the community with academic coursework; training students to help guide other students in resolving conflicts peacefully; addressing matters relating to bullying and harassment; developing strategies to help students understand and manage their anger; teaching students the dangers of drug, alcohol and tobacco use and abuse; and developing skills for managing conflicts, building positive social skills and practicing the importance of acceptance, respect and empathy.

By focusing on character development and coping skills from an early age, Rector said students will more easily be able to navigate positive and negative social situations, avoid falling into isolation or depression and be able to better handle academic pressure in middle or high school.

"Anything we can do to help give students the opportunity to feel successful is important," she said. "That's why we've increased the number of elementary school counselors over the last couple of years, as well as in middle schools, and increased the number of social workers we have."

Social-emotional specialist

The Salina school district also has hired a full-time social-emotional specialist, Sarah Lancaster, who has been in place about a year and a half. Lancaster said her role is to help schools create time in their day for intentional relationship building with students, including those with behavioral or trauma issues.

"In an effort to create behavioral change and not just enforce a punishment, mediation can be utilized when there are issues between students, or between a student and teacher, to help process the problem," she said. "Creating time for intentional relationship building with all students builds the foundation for students to feel safe at school, to know they have adults who genuinely care about them and to have a connection with their peers. Having these elements in place is critical in order for academic learning to take place at its highest potential."

Integrating social-emotional and character building skills into the classroom might be done through written expression of feelings through journals, poetry and essay writing; reading and identifying how certain passages reflect emotions; using art or computer-generated models to convey emotions; or building skills through games, videos and role playing in group formats.

"There's no one program or solution to such a diverse, complex issue," Rector said. "One school's need may be very different than another's. But we're moving away from a more reactive approach to a more proactive approach to social-emotional support."

Addressing mental health

But what about students who have experienced trauma or have mental health issues that might need stronger proactive intervention?

Tiffany Anderson, superintendent of USD 501 in Topeka, has spearheaded a tiered level of support to address mental health services in her school system. A mental health committee that she chairs provides support and training that addresses acute and chronic traumatic events involving students and staff.

To support staff in developing a deeper understanding of trauma, Topeka Public Schools has partnered with the Houston-based Child Trauma Academy to offer Neurosequential Model in Education (NME) training. The academy has developed a set of training courses to help school counselors, administrators, teachers and support staff understand student behavior and performance, based on students' brain development and developmental trauma.

The district also has partnered with the University of Kansas to develop a Comprehensive, Integrated, Three-Tiered (Ci3T) model of prevention, constructed to address academic, behavioral and social issues by maximizing available expertise through professional collaborations among school personnel.

"All of our schools have had training, with a focus on behavioral, academic and emotional support," Anderson said.

Anderson said curriculum materials also are being introduced into the classrooms by counselors that address social-emotional issues that include anti-bullying and suicide prevention, which Anderson said is the second leading cause of death for children ages 10 through 14 in Kansas.

There also are 15 therapy dogs available in the district's middle schools for student use, she said, as well as mental health rooms that allow students to excuse themselves from class and "let off some steam" to regulate their emotions with the assistance of available counselors.

"We're giving a strong message that (mental health) is of the greatest priority," Anderson said. "You look nationally at school shootings and find individuals with mental health issues from an early age. Kansas has a high rate of teen suicide, and that is often related to depression. That's why we've approved adding student mental health as part of our strategic plan."

Anderson said she hopes the mental health strategies that Topeka is piloting will expand statewide.

"We hope the state can use this to further implement quality mental health services for students in Kansas," she said.

READ MORE

Medicaid expansion prospects uncertain

Native American chef teaches cooking, nutrition to tribes nationwide

Nurse practitioners eye change of law in Kansas

VA hospitals, clinices in eastern Kansas provide array of services

Kansas universities involved in wide-ranging medical research

Telemedicine enables providers to reach rural patients

Kansas teen pregnancy rates dropping

READ MORE

Social-emotional learning teaches youths how to manage emotions

Research solidifies estimates for Medicaid expansion

Taking steps to understand, prevent physician burnout

Innovative recruiting in southwest Kansas offers hope amid doctor shortage

Rural communities face critical issues in caring for elderly

KU Med School making efforts to place doctors in rural areas, small towns

Staffing for elder care at 'crisis level'

KU-sponsored collaborative helps with critical care issues in rural Kansas