TRANSPARENCY UNDER ASSAULT

Lynn Farinelli is a Pawtucket stay-at-home mom. Dimitri Lyssikatos is a Providence mechanic. They were strangers until they shared online their frustrations with the Pawtucket police department withholding internal-affairs reports.

Farinelli had filed a complaint over the way detectives investigated her son’s death.

Lyssikatos wanted to know why an officer had demanded he show his driver’s license during a traffic stop for an expired inspection sticker. Lyssikatos was a passenger in the car.

“I believe in civil liberties,” Lyssikatos says. “I said to him: ‘I have my ID in my pocket, but I don’t feel you have reasonable suspicion to start demanding an ID from everybody in the car.’ He proceeded to go on a rant: ‘You want to be like that? Get out. I’m going to search the car.”’

So began the pair’s long journey for police internal-affairs records across the state — documents that the state Supreme Court ruled decades ago were public reports (with officers’ identities redacted).

They are not alone. Perhaps more than ever before, say municipal officials, people are asking for information — and accountability — from their government, raising debates over the public’s right to know versus privacy protections in this Google world of perpetual exposure.

In Portsmouth, Rick Bruno waits to read the full report on his son’s suicide that the School Committee refuses to release.

In East Greenwich, Town Council President Mark Schwager is promising a new era of open government after the old council — all but one of whose members were either voted out of office last fall or who didn’t seek reelection — was cited seven times in about a year for violating open-meetings laws by conducting town business behind closed doors.

“That was a council that really did what it wanted and asked questions later,” said Schwager, the only incumbent reelected. “The open-meetings violations were indicative of that.”

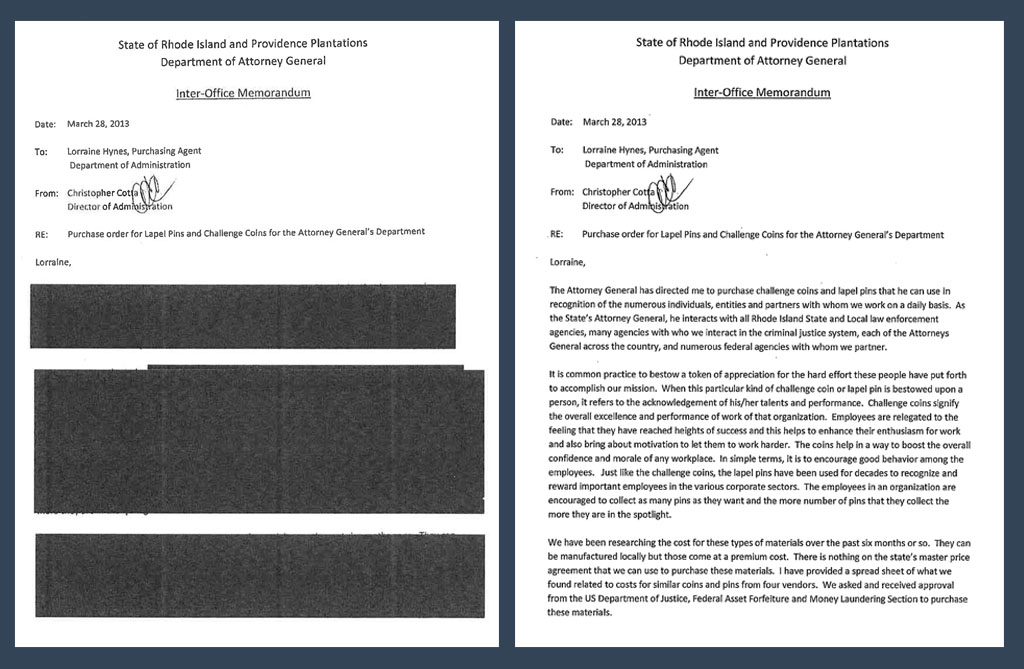

In Coventry, former state Rep. Patricia Morgan keeps a copy of “that memo” on top of eight boxes of heavily redacted documents that the office of Attorney General Peter Kilmartin charged her $3,750 to receive. She had filed a formal information request on how the office had spent the $59 million in Google settlement money it received for its role in exposing a shady prescription-drug marketing technique.

The innocuous memo — three paragraphs about the attorney general ordering lapel pins — was entirely blacked out, save for the subject line.

“They took their sweet time going through everything and redacting stuff that was foolish like that memo because they had decided to chew up the time [the law allows for replying] and make it prohibitively expensive,” says Morgan.

When the American Civil Liberties Union of Rhode Island requested the same memo from the new attorney general, Peter Neronha, it received an unredacted version.

The memo is symbolic of more than just arbitrary decision-making, says Steven Brown, executive director of the American Civil Liberties Union of Rhode Island.

More troubling is the rationale Kilmartin’s office used to defend keeping the memo secret: under its interpretation of the state’s Access to Public Records Act, memoranda now fit the criteria of “preliminary” documents that are exempt from disclosure.

That interpretation has never been advanced before, says Brown, and risks tens of thousands of memos being labeled secret that are produced routinely in the course of state and local government business. Withholding such public information is “a direct assault on transparency and the very concept of open government.”

An evolving battle

In recent years, fighting for open records has been the equivalent of playing the arcade game Whac-a-Mole, says Brown. “You think you’ve solved one problem, and another one comes up.”

Some public officials, enabled, perhaps even emboldened, by other controversial advisory opinions from Kilmartin’s office, “have come up with creative ways to circumvent” the Access to Public Records Act.

The battle is going on in real time.

On Wednesday, a Superior Court judge heard arguments in a lawsuit brought against the Pawtucket police by the Rhode Island Accountability Project, the nonpartisan group started by Lyssikatos and Farinelli to gather internal affairs reports from police departments around Rhode Island and post them online.

The city refused to release 57 complaints against police officers, filed over a two-year span, citing officer-privacy issues and a distinction that Brown says the Supreme Court never made: that internal-affairs reports generated within the department are different from those prompted by citizen complaints; they are more like personnel matters, which are private.

Lawyers for the two sides are also asking Superior Court Judge Melissa Long to wrestle with the “balancing test” that the open-records law allows public officials to consider, weighing the public service the documents would provide and the potential invasion of privacy. The judge said she would rule on the issue on March 18.

Lyssikatos and Farinelli sat in the front row in court.

“We feel nobody can have faith in the integrity of a police department investigating themselves if you can’t go back and look at what they’re doing,” says Lyssikatos.

But in an interview Wednesday, Pawtucket City Solicitor Frank J. Milos Jr., who denied the request for the reports — even though police identities were redacted — said, “Police are people, too, and they have a certain level of privacy in personnel matters, and I didn’t think the case law was so clear that when the [state] Supreme Court rendered their decision 20 some odd years ago they meant that these types of reports should go out as well.”

Though Pawtucket has been cited in recent years for violating the open-meetings law, “we don’t not give records just because we don’t want to,” he said.

Milos noted that when he began working in the city’s legal department more than 20 years ago, “I don’t think in my first five to eight years I ever saw an APRA request.” Now, “we easily get over 150 of these a year.”

“I find myself here virtually every Saturday, because I need to have the peace of mind of not having distractions and I can look through the APRAs that are due over the course of the next week or two.”

Milos said, “I do rely on the attorney general’s office and the opinions they render, and I do cite them frequently because, let’s face it, their decision means more than mine does” if someone appeals his denial of records..

But Milos said he also worries about prompting a lawsuit against the city if he releases a report that violates a municipal employee’s privacy.

“I have to be worried. I may be the APRA guy, but I’m also the city’s attorney. I have to balance everything. I have to be forward-thinking. I have to look ahead to what tomorrow’s lawsuit is that maybe could have been avoided if I just maybe had taken a step back and thought it through a little bit better before I released the document. Once I release it, it’s out there.”

‘The long tail of the internet’

Frank LoMonte directs the Joseph L. Brechner Center for Freedom of Information at the University of Florida.

Around the country, a “cultural shift” is under way with government agencies and colleges “obsessed with promoting a positive public image,” he says. “It’s become an accepted and legitimate use of government authority to use that authority to have people think favorably of the government. We used to call it propaganda.”

The reason? “It’s primarily the long tail of the internet,” LoMonte says. “It used to be if you suffered a bout of unfavorable publicity, it went into the recycling bin at the end of the week with the newspapers.”

Now, unfavorable publicity “can contaminate your Google results for a long time. … So people in media relations in the government seem to be much more sensitive to the unflattering news story than they would have been 20 years ago. There’s far more intolerance to negative publicity.”

Last month, the former press secretary of ex-Atlanta Mayor Kasim Reed was charged with two misdemeanors alleging she violated that state’s open-records law by stonewalling a television station’s request for public records from the city water department.

The press secretary allegedly instructed the water department’s spokesperson to “drag this out as long as possible” and “provide information in the most confusing format available.”

State Attorney General Christopher M. Carr brought the charges, calling it a first-of-its-kind prosecution for open-records violations in Georgia: “Openness and transparency in government are vital to upholding the public trust. I am confident that this action sends a clear message that the Georgia Open Records Act will be enforced.”

Open-government advocates in Rhode Island say they wish Kilmartin had been such a champion for public access.

“His office was not particularly strong with public records and open meetings,” says John Marion, head of the open-government group Common Cause Rhode Island.

Kilmartin could not be reached for comment on this story. His former spokeswoman sent him a text message as well, but told The Journal that Kilmartin may be traveling. Michael Field, the former head of Kilmartin’s open-government unit, who authored many of the attorney general’s advisory opinions, did not return a telephone call to his office.

Over the years, local town councils, school committees and fire districts have been the most- cited violators of open-records and open-meetings laws.

In an excoriating decision in November 2017, Superior Court Judge Susan E. McGuirl said the East Greenwich Town Council’s secret decisions surrounding the appointment of Gayle Corrigan as town manager “misled the people of East Greenwich. …Public service is an honor. … The process is done in the light, not in the dark.”

While Kilmartin’s office never ruled that the council had willfully violated the Open Meetings Act, McGuirl did, and imposed a $2,000 fine.

“Boy, did she really write an incredibly insightful message to the town that I really took to heart,” said Schwager. “What she said was so relevant, not just for East Greenwich but far beyond.”

Access vs. privacy

But some elected officials have cited concerns over possible privacy invasion as a reason for not releasing documents to the public.

Nathan Bruno was 15 and had formerly played on the Portsmouth High School football team.

Last year, he and possibly others harassed the team football coach with text messages. When the coach threatened to quit unless his team helped identify any accomplices, Nathan Bruno committed suicide.

The School Committee hired a Providence lawyer to investigate what precipitated Nathan’s death. He interviewed dozens of people and says he promised many of them confidentiality to tell what they knew.

The committee used his report in deciding not to reappoint the coach. But the committee, citing the privacy of those interviewed and other exemptions in the state’s public records law, has kept the full report secret, though it read a summary of findings at a meeting.

In 2017, Secretary of State Nellie Gorbea, without public notice or hearing, removed the full dates of birth from the state’s database of 778,000 registered voters after she says she consulted with cybersecurity experts who raised the threat of possible identity theft.

In an interview Wednesday, Gorbea said the move was “one of the most challenging and most thought-through decisions” she had made in her first years in office because she believes in “government accountability and transparency.”

Last November, Gorbea rejected a request by a Journal reporter for a digital copy of the Rhode Island voter database, with full names and birth dates for each voter — information that had been provided to the newspaper in the past. The Journal has since filed suit, noting that in the past, through independent examination and matching of voters’ birth dates, the newspaper had found errors in the voting list.

For instance, in 2006 the newspaper found about 10,000 duplicate voter registrations and an additional 5,000 listed eligible voters who were actually dead.

In 2016, The Journal also found that the database had about 189,000 more voters on it than would be expected, based on federal census records.

Marion, of Common Cause, says its board hasn’t yet taken a stand on Gorbea removing the full dates of birth from the database.

“Today,” Marion says, “a person who buys the entire voter file can put it up on a website, and that wasn’t possible in 1986” when The Journal first successfully sued for public access to the voter information.

Those kinds of technology advances “requires us to think about what unfettered access to the voter file could mean.”

New AG, new philosophy

Neronha, the new attorney general, has made it clear that his office’s philosophy regarding open records will be different than his predecessor’s.

“My overall philosophy, and this applies to open meetings and APRA, is: “simply because this is the way we’ve done things in the past, I don’t believe necessarily that’s the way we should do things moving forward.”

For instance, while Kilmartin’s decision regarding the Morgan memo may have been a reasonable legal interpretation, “I don’t think it’s the right one. … When I look at the memorandum issue, it doesn’t make a lot of sense to me that you can withhold a memorandum simply because it says that at the top of the document.”

Neronha has called for a review of how Kilmartin handled Morgan’s request for information.

The ACLU’s Brown says that while Neronha’s words sound encouraging, “time will tell. I don’t think it can get worse than it has been.”

A user's guide to R.I.'s Access to Public Records Act

For records kept by state and local government agencies, as well as quasi-public agencies, in Rhode Island, turn to APRA. The Access to Public Records Act is the state law that explains what records are public and how they can be obtained. The law also applies to judicial bodies, although limited to administrative functions.

The definition of a public record in APRA is both broad and narrow. "Public records" are defined as all materials generated or collected by public entities in connection with the conduct of official business, such as documents, films and photos, recordings, letters, maps, electronic data processing records and some emails.

However, there are multiple exemptions. Investigatory records of public agencies are mostly exempt, as are personnel records. Other exemptions include medical records and information related to attorney-client privilege, tax returns, library records, statements and strategy of labor negotiations, as well as trade secrets, scientific and technological secrets, and security plans of military and law enforcement agencies. Preliminary drafts and working papers are exempt, until they are submitted at a public meeting. The public also doesn't have access to child custody and adoption records, records of illegitimate births, and records of juvenile proceedings before Family Court.

What's public? While personnel records are exempt, the public still has a right to know information about employment contracts and salaries, overtime and benefits, job titles and dates of employment. Pension records of current and retired members of the public retirement system are public.

Police logs are public, and the initial arrest of adults must be made public within 48 hours, or 72 hours if over a weekend or holiday. While law enforcement records relating to investigations and detection of crime are exempt, that's under certain conditions: when the release of the records could be reasonably expected to interfere with investigations of criminal activity or law enforcement proceedings, would deprive someone of a fair trial, could be reasonably expected to constitute an unwarranted invasion of personal privacy, could disclose the identity of a confidential source, endanger someone's life, or disclose techniques or guidelines for investigations or prosecutions.

Once you know what agency has the records you're looking for, you can send a letter or email requesting information. Most agencies also have places on their websites that specify how you can submit a request directly.

Cite the law — Rhode Island General Laws, Chapter 38-2 — and be specific about what you want and how you would like to receive the information, whether mail, fax or email. Agencies may charge up to 15 cents per page to copy records and up to $15 an hour to search for your documents, with the first hour free. Include the amount you are willing to pay and ask to be contacted if the cost runs over.

You do not have to give a reason for your request. Even if you do, an agency can't deny you because of your reasons. The agencies have 10 business days to grant the records, but may request an extension of up to 30 business days if they can show the request is time-consuming.

If the agency doesn't respond by the deadline, or otherwise denies your request, you can appeal to the agency's chief administrative officer, or file a complaint with the attorney general's office or in Superior Court.