The first signs of change came to Belmont County several years ago, as natural gas extraction company trucks rumbled over the roads.

Next came drilling rigs and pipelines for hydraulic fracturing, also known as fracking. To many, the pipelines are a lifeline in impoverished Appalachia, bringing in jobs and money.

BUT AT WHAT COST?

Despite the economic boom, environmentalists and some residents are questioning the health and safety of fracking, which has brought leaks, fires and explosions.

Six years ago, oil and gas company Antero Resources showed up in Belmont County, promising money to a struggling community in exchange for rights to drill on residents’ land.

Oil and gas companies promised thousands, and in some cases millions, in an area where an estimated 14% of county residents live below the federal poverty level.

Many in the community signed on.

In Barnesville, a village of about 4,000 people, 80% of landowners signed leases to allow Antero to drill for natural gas on or under their land. Schools have received an influx of money, and about 150 oil and gas jobs have been created in the county.

But now a growing number of residents in eastern Ohio are wondering whether they are paying too high a price for the fracking bonanza.

People “just heard money and they were lined up, you know, clear around the (Barnesville) high school. Hundreds and hundreds of people (were) waiting to get in to sign up. That was very alarming to me just to see how blindly everyone embraced the industry,” said Jill Hunkler a 44-year-old Barnesville resident, who says she has suffered health problems because of the drilling. She became an environmental activist.

Fracking in Belmont County

Environmentalists and some residents are questioning the safety and health effects of the industry.

Courtney Hergesheimer | Dispatch video

Fracking in Belmont County

Environmentalists and some residents are questioning the safety and health effects of the industry.

Courtney Hergesheimer | Dispatch video

Amid the drilling boom, environmentalists and health experts have descended upon Belmont and neighboring Appalachian counties in an effort to measure the impact of hydraulic fracturing, known as fracking, on water quality, air emissions and even emotional health.

“The evidence is strengthening and growing. Several studies demonstrate the potential for health problems,”said Nicole Deziel, an assistant professor at the Yale School of Public Health, who has traveled to the region for three years to study air and water quality.

Nicole Cardello Deziel, PhD, MHS, a researcher from Yale School of Public Health, has been conducting water and air studies in Belmont County, Ohio, in relation to the gas extraction and processing in the area. Courtney Hergesheimer | Dispatch photo

“Scientists are quickly conducting health studies to better understand whether there are health impacts or not.”

Activists say the clock is ticking. They hope to have clear findings before the oil and gas industry potentially takes a big next step.

Chemical company PTTGC America, based in Thailand, is considering building a “cracker” plant on the west bank of the Ohio River in Belmont County that would convert an oil and gas byproduct into ethylene, a key ingredient in producing plastics and chemicals. Such a plant could produce hundreds of high-paying jobs and potentially draw plastics plants seeking access to the ethylene.

This month, JobsOhio, the state’s economic development nonprofit agency, awarded a $30 million grant to ready the site, and PTTGC America already has invested more than $100 million to conduct engineering designs.

“I am very hopeful we’re going to get a final decision … and get to the point where they can move forward,” said Larry Merry, executive director of the Belmont County Port Authority.

The cracker plant would be the largest economic development project in the state.

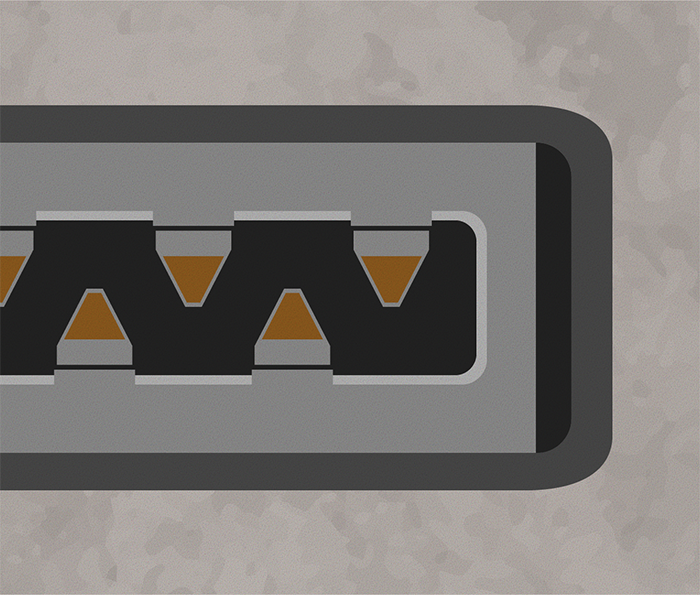

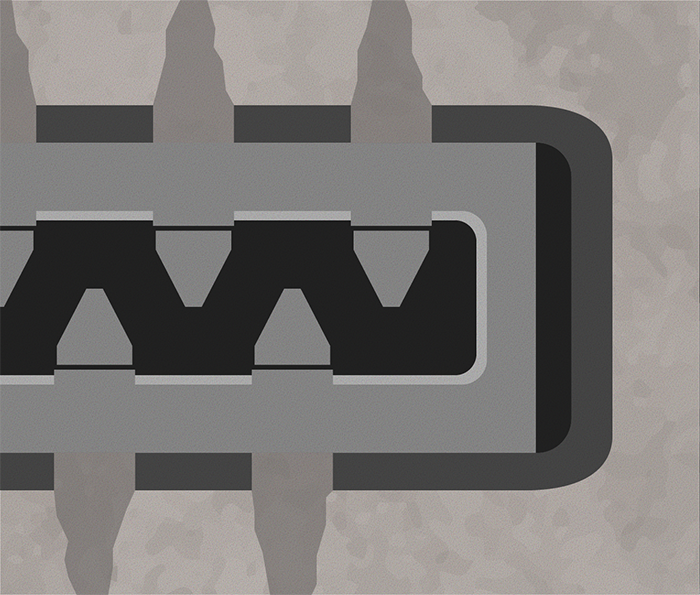

How does fracking work?

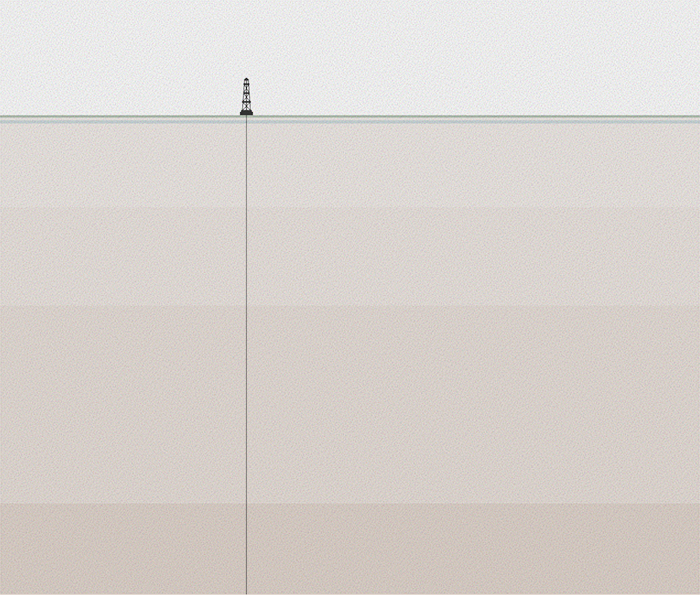

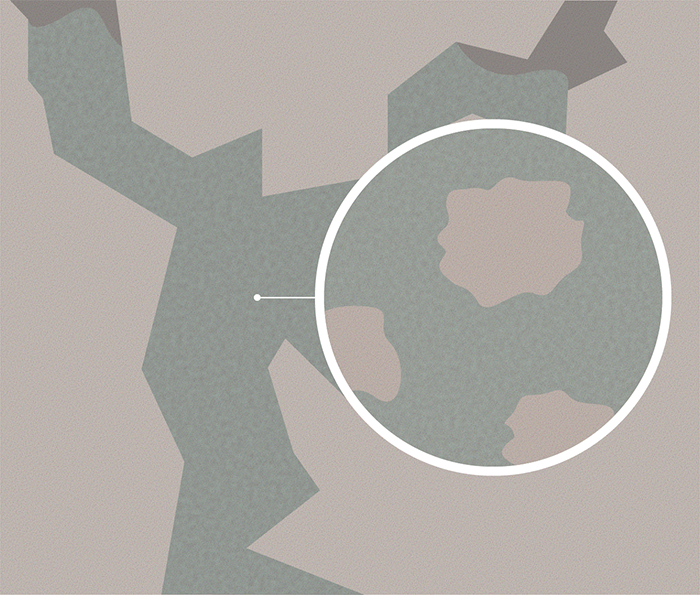

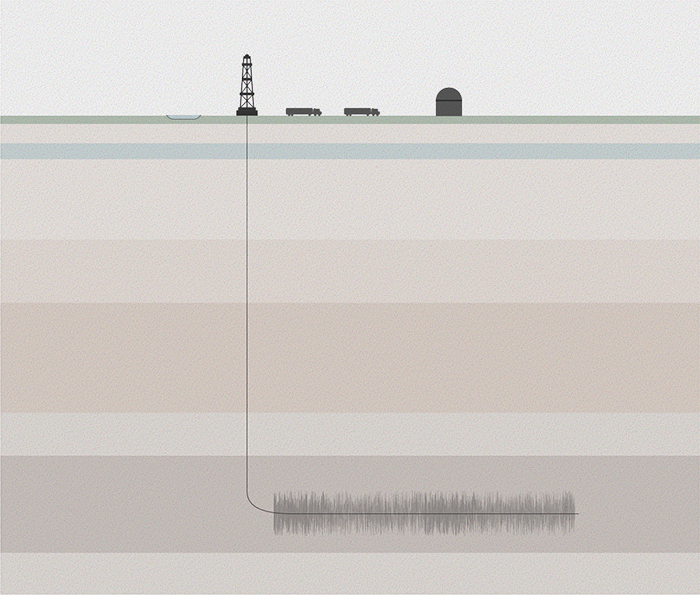

The process of fracking begins with locating a deposit of shale rock that holds natural gas. Ohio has Devonian-age Marcellus Shale which has been extensively drilled throughout the eastern part of the country. In the last several years, Ohio has experienced a boom in Ordovian-age Utica Shale wells.The Utica offers “wet” gas also known as natural gas liquids.

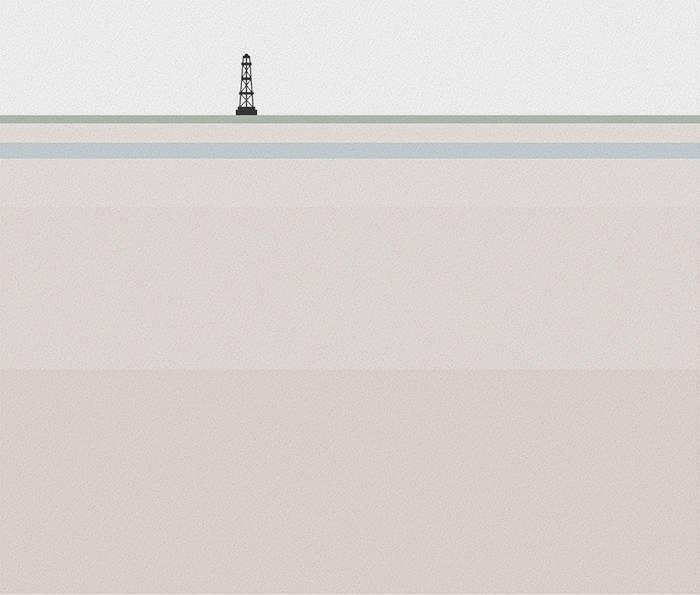

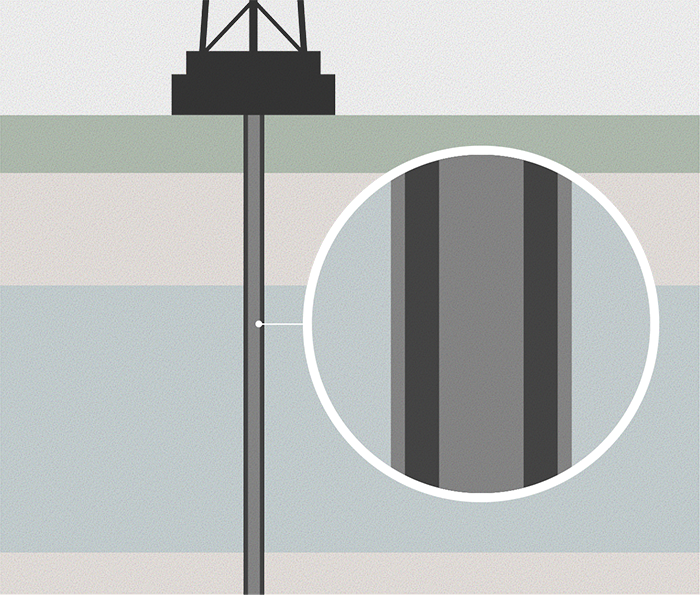

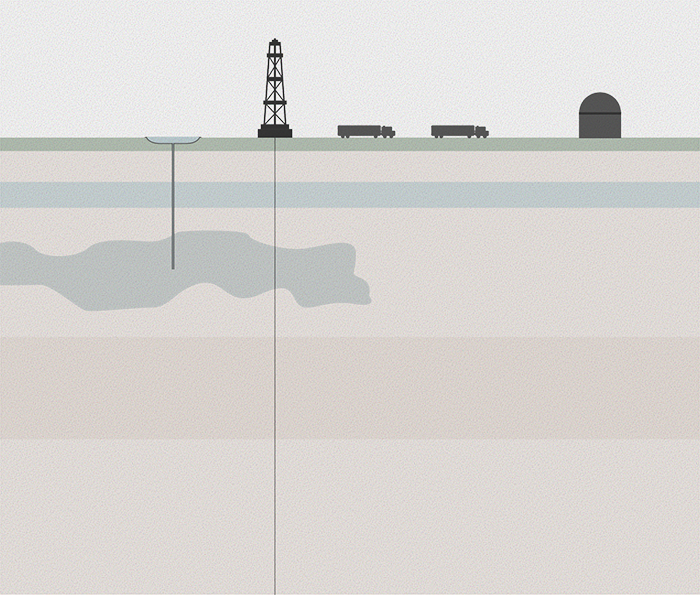

The well is drilled and passes through each layer of the earth, including 150 feet below where groundwater is present.

To protect water sources, layers of concrete are pumped around the sides of the well and coated in layers of steel. The number of layers added to this surface casing differs between companies and locations.

After passing through water tables and aquifers, the well is drilled further into the earth until it reaches the layer of shale rock where the gas can be extracted. As the drill reaches deeper, less layers are added to the outside of the well casing.

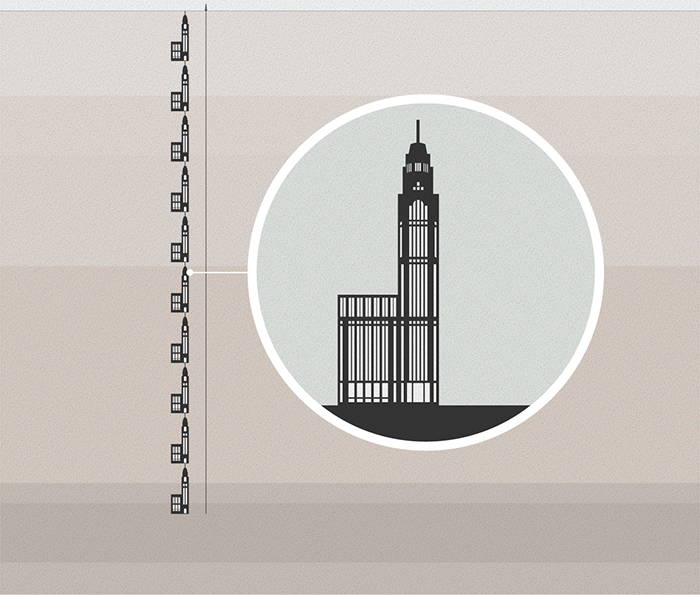

The shale layer is located one to two miles underground. It would take at least 10 LeVeque towers – standing at 555 feet tall each – stacked to reach this depth underground.

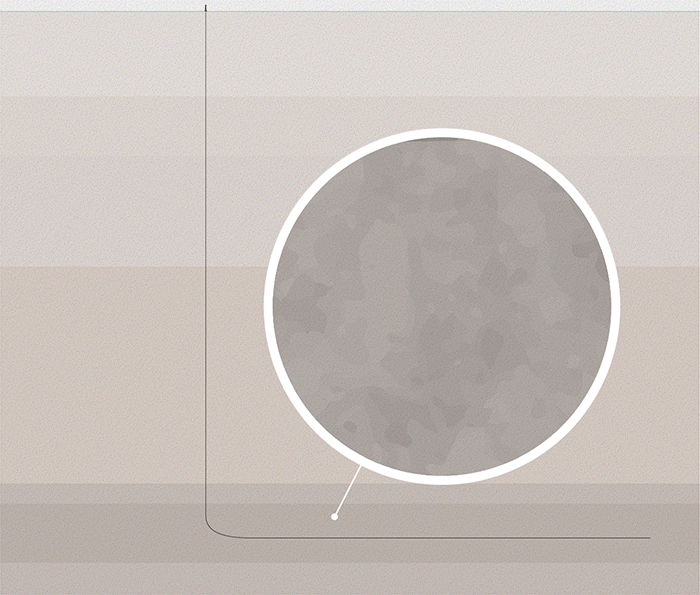

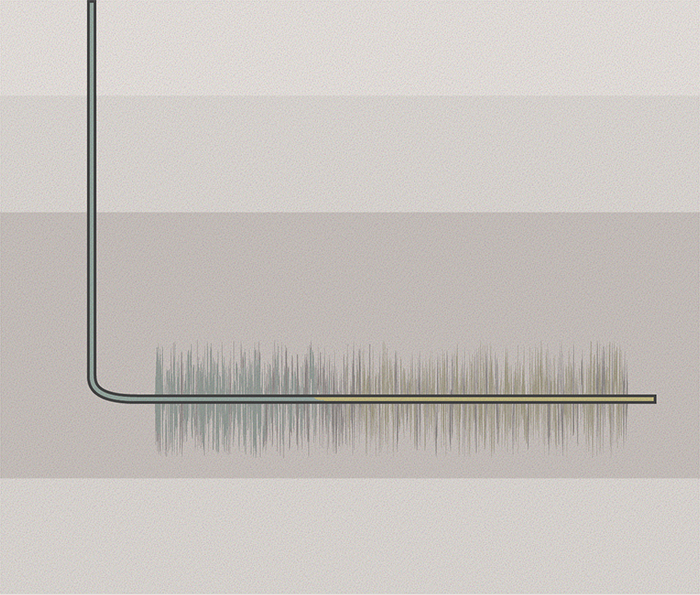

Once the drill reaches the layer of shale rock, it makes a 90-degree turn and reaches horizontally another 6,000 feet or more.

At the end of the well, a cap is inserted and a perforating gun is loaded into the end of the well. The gun carries explosives to puncture holes through the sides of the well casing and into the shale rock.

The explosives break through the walls of the well and into the shale rock which creates small cracks.

Fluid is pumped into the well, forcing the cracks created by the perforating gun to break open into longer and larger fractures.

This part of the process is where the name “hydraulic fracturing” or “fracking” comes from. The small cracks are full of fracking fluid at this stage of the process. The fluid is made up of water and chemical additives.

The fluid that’s pumped into the shale rock contains sand particles that hold the cracks open so gas can flow out. The fluid also contains a mixture of chemical additives. These chemicals vary in type and function between companies.

This process of capping and perforating the well and fracturing the rock is continued in small sections until the length of the horizontal well has been fractured. The excess fluid flows out of the well followed by the shale gas.

The fluid that is recovered is transported to a holding pond, a class 2 injection well, treatment center or is recycled. According to ODNR, 98% of brine is disposed of while 2% is used to de-ice roads. Nationally, there are 151,000 class 2 injection wells. Ohio is one of the states that permits the wells.

The fluid can not be put back into the groundwater because of the chemicals involved in the process. The gas is transported to a treatment center and the well remains operational until the gas supply is depleted.

Emily Wright | GateHouse Media

Winners

The boom in drilling for oil and natural gas in Ohio is nowhere louder than in Belmont County, about 120 miles east of Columbus. It produced more natural gas and brine waste from the hydraulic fracturing process in the first quarter of this year than any other Ohio county, according to Ohio Department of Natural Resources data.

Plenty have benefited.

A Farmer’s Land

A local dairy farmer and land owner talks about leasing land to companies for fracking.

Courtney Hergesheimer | Dispatch video

A Farmer’s Land

A local dairy farmer and land owner talks about leasing land to companies for fracking.

Courtney Hergesheimer | Dispatch video

Some families who own hundreds of acres and decided to lease their land are now millionaires. Larry Cain, 61, of Bethesda, and his family leased 280 acres. Cain, along with a group of 800 leaseholders, collectively leased 34,000 acres. Just to sign up, the group received more than $200 million.

“I would say probably everybody has a new pickup truck and they have newer tractors and equipment that’s safer to operate, but you don’t see … what I would say is an extravagant lifestyle,” he said. “People remodel their kitchens — things like that — that was probably always needed but they never had the money to do it.”

Larry Cain looks out at one of the two natural gas well pads, on his small dairy farm that he inherited from his father and runs with his son, near Bethesda, Ohio, in Belmont County. Courtney Hergesheimer | Dispatch photo

Hydraulic fracturing drill pad named “Krazy Train” one of the two natural gas well pads, on the small Cain family dairy farm. The Cain family was one of many land owners that got together to lease their land as a group. Courtney Hergesheimer | Dispatch photo

Belmont County home prices have risen from a median sale price of $92,000 in September 2013 to $128,000 in September 2018, according to the East Central Association of Realtors. In addition, the state has collected $58.4 million in severance taxes from natural gas extraction, which funds the regulation of the industry.

Severance tax collections

In millions of dollars

The severance tax, which was enacted in 1972, is paid by firms that extract, or server, certain natural resources from the soil or waters of Ohio. Since 2014, the amount of tax collected for natural gas has increased while taxes collected for coal and oil have decreased.

Natural gas is taxed at 2.5 cents per 1000 cubic feet (Mcf), coal is taxed at 25.2 cents per ton and oil is taxed at 10 cents per barrel. Source: Office of Budget and Management fiscal reports

Schools also have seen a jump in revenue from taxes collected on the gas and other minerals.

The St. Clairsville-Richland City School District is in the process of collecting $835,000 in fiscal years 2018 and 2019. The amount received in 2018 represented less than 2.5% of the district’s overall budget.

That money isn’t guaranteed.

The revenue so far has gone to one-time expenses such as new school buses, laptop computers and deferred maintenance.

Union Local Schools in Belmont County plans to use its gas-tax income on new heating and cooling systems and security upgrades, said Superintendent Ben Porter, who believes the industry on the whole has benefited the region, while acknowledging health concerns.

“There are more employment opportunities as a result, and environmental concerns. You do have those as well,” Porter said. “But from our standpoint, we have pretty good relationships with the oil and gas business. And it has been something that’s good just in terms of the extra revenue that it has generated.”

Humphreys compressor station, near Barnsville, Ohio. Courtney Hergesheimer | Dispatch photo

The industry has created jobs in Belmont County, though they can be measured in the hundreds, not the thousands, said Andrew Thomas, who works at the Energy Policy Center at Cleveland State University.

“The new jobs in the oil and gas industry are not sufficient to offset the decline in other industries, particularly the coal industry,” Thomas said. “I think a lot of the jobs being created … are not going to be really high-paying jobs, which is why we really want to see that cracker plant come in that can create more jobs that are in the construction and in higher-paying areas like plant management.”

Health effects

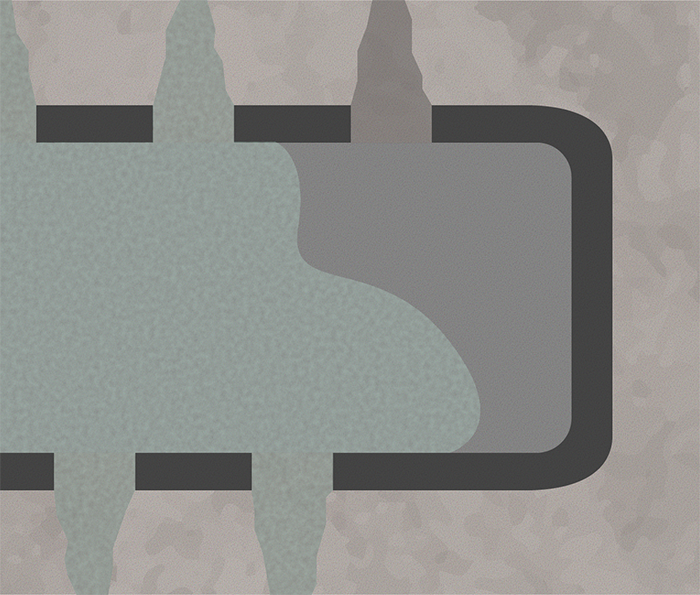

In 2012, there were nine wells drilled into the Utica shale layer of rock about a mile beneath Belmont County. As of June 29 of this year, there were 654 wells, with 456 producing. The county has eight wells in the Marcellus shale layer, which is not as deep as the Utica.

Wells are drilled to extract natural gas and oil from Devonian-age Marcellus shale and Ordovician-age Utica shale layers found in eastern Ohio. Once natural gas deposits are found, the companies drill down to the shale and turns at a 90 degree angle and can extend as much as a mile or more.

Then they inject millions of gallons of water, sand and chemicals underground to fracture the shale and free trapped oil and gas. Fracturing fluid including additives and chemicals is pumped in to fracture the rock, which allows oil and gas to be extracted.

A farm house shares its backyard with the Eclipse owned Boyd Hall well pad in Belmont County. Courtney Hergesheimer | Dispatch photo

Statewide, there were 400 Utica wells in 2012 and 3,117 wells as of June 29 of this year — a 679% increase. There are 67 Marcellus shale wells.

Scientists such as Deziel are trying to study the effects of an industry that has expanded rapidly. There’s a lot at stake.

More than 4 million Americans live within a mile of unconventional oil and gas wells, which could subject them to toxic releases, according to a study released last year by Deziel and a team of Yale researchers. More than 9 million Americans have drinking water sources within a mile of oil and gas wells.

How close do you live to a well?

Explore permitted fracking wells near you in Ohio

Of Ohio’s 88 counties, 24 are populated with fracking wells.

In a study released last year by Yale researchers, 66 Belmont County residents were interviewed about health effects since the oil and gas boom. Many reported respiratory symptoms, general stress and fatigue and headaches, with 92% of people reporting at least one symptom.

The study did not find a specific connection between the drilling and health problems, but did support further analysis and monitoring to determine whether oil and gas activities were affecting drinking water.

Researchers from Yale School of Public Health test the water at the home of Jill Antares Hunkler in Barnsville, Ohio. There are now seven gas development sites in a two mile radius of her home, Humphreys compressor station being the closest. Courtney Hergesheimer | Dispatch photo

Nicholaus Johnson, left, and Min Chen, right, test the water at the home of Hunkler. She has stopped staying at her home full time because of headaches and is strongly considering leaving her land. Courtney Hergesheimer | Dispatch photo

Earlier this month, about 100 people attended a meeting at the Ohio University branch campus in St. Clairsville to hear about a proposed injection well that would be used to store waste water from fracking waste in the county. They also heard more about Deziel’s research.

Mike Bianconi, 62, who lives in the town of Pease in Belmont County and is a township trustee, attended the meeting.

“I’m not worried about me. I’m worried about the next generation … Usually it takes a long time for things to come down,” he said.

Mike Chadsey, director of public relations for the Ohio Oil and Gas Association, said no one has a reason to be concerned about health issues.

“I think it’s been studied ad nauseam. And I think if we had a problem with water, we’d know about it,” he said. “We’ve been doing this since 2011. If you go back to conventional development — 1880 — if we had a problem, we’d know about it. We don’t.”

Jill Antares Hunkler lives on her family’s land in Belmont County, Ohio, where she performs healing rituals. Courtney Hergesheimer | Dispatch photo

Hunkler, who has well water at her home in Barnesville, had water tested from Slope Creek near her home. A couple of contaminants were found, but at levels below the federal Environmental Protection Agency limit, according to the results. About a dozen contaminants were tested for in the first round of tests by Yale researchers a few years ago.

“I was really concerned about that … Of course, immediately I want to blame the industry, you know, but to be able to prove that that is the industry?” Hunkler said. Her well water is being tested during this latest round of tests by Yale researchers, who will now be testing about 100 compounds found in the water.

Hunkler does yard work around her home. With seven gas development sites in a two mile radius of her home, Jill has stopped staying at her home full time because of headaches and is strongly considering leaving her land. Courtney Hergesheimer | Dispatch photo

Cain also is participating in the study a second time. He said his water was tested at safe levels a few years ago.

“If we truly believe that they’re doing this in a responsible way, we should be willing to participate in things like this. If they’re not, then we want to be aware of that and the company should respond to that,” he said.

Deziel said EPA drinking water standards have not been updated recently and might not reflect the most current research on safe levels. With more data, standards and guidelines are often altered. For example, for years, federal guidelines called for a much higher acceptable level of lead in blood.

“Now, scientists and doctors agree there is no safe level,” she said, citing the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Environmental questions

Hunkler lives about a mile away from the Humphreys compressor station, which pressurizes and moves natural gas through the pipeline.

The facilities are required to track nitrogen oxide, carbon monoxide and volatile organic compound emissions. Nitrogen oxide and volatile organic emissions form ozone on hot days. High enough levels can cause respiratory issues for sensitive groups, such as those with asthma.

The area around Jill Hunkler’s house has become home to numerous fracking wells. There were no wells present in the area in October 2006, but by October 2015 they had been developed. Google Earth | Satellite photos

MarkWest, a subsidiary of Marathon Petroleum that specializes in compressor stations, hired a third-party company, Air Hygiene Inc., in April to perform its tests. Ohio EPA allows companies to hire an outside company to test emission levels and the results are submitted to the state agency.

“There is an obligation by the facility to report accurately. And there’s a pretty significant difficulty on the part of the facility to not do it properly. That will typically wash out through the inspection process,” said Bryon Marusek, manager of ambient air operations for air pollution control for the Ohio EPA.

Inspectors are trained thoroughly and initially have to partner with experienced colleagues. The people who collect the data for the company also are interviewed by state inspectors, he said.

Levels were well below guidelines for Humphreys, according to an inspection report. Records show the compressor station had one violation in 2016, when it went above permitted limits.

A federal consent order shows the company was required to install an Air Defender System — a vapor recovery system that reduces harmful emissions — in 2018. The system was installed in mid-2018.

Robert McHale, Northeast Environmental Director for MarkWest Energy Partners, signs in to the Humphreys Compressor station. A compressor station pressurizes natural gas after it has been extracted from the ground. Courtney Hergesheimer | Dispatch photo

“Environmental stewardship is one of our company’s core values, and given the success of the Air Defender System, we have now installed the system at all of our compressor stations in Ohio,” said Robert McHale, northeast environmental director for MarkWest.

Looking at the station with the naked eye, there are no visible emissions.

But Leann Leiter, an advocate who works for the environmental nonprofit group EarthWorks, uses an infrared camera to document emissions from oil and gas sites.

“We’re providing visual proof of what nearby residents have been observing and suspecting for some time and kind of giving them something to stand behind when they might be told by the operator: ‘There’s nothing coming out of that facility.'” she said. “This technology enables us to show people these facilities are not harmless and they are not free of pollution.”

Pete Dronkers, staff and cameraman for Earthworks, an environmental nonprofit, looks for gas leaks at Humphreys compressor station, using a FLIR, an infrared camera that detects heat and gas plume, in Belmont County. Courtney Hergesheimer | Dispatch photo

Sanjay Krishna, who studies infrared technology in Ohio State University’s engineering department, reviewed the footage from Earthworks.

“I would think that the signature is a mixture of thermal and chemical signatures, and further experiments would be needed to separate the two effects,” he said.

McHale said no one should be concerned about health issues regarding emissions from the companies’ compressor stations.

“I can tell you, because I have been here to collect the data. I have seen the results. I’ve seen third-party studies. There’s absolutely no legitimate concern for human health or safety,” he said. “I don’t live next to one of our facilities, but I absolutely would.”

Fracking-related problems

Statewide, 293 spills, leaks or fires were reported at oil and gas sites in 2018. Fifteen incidents — including the most severe — were reported in Belmont County, according to the Ohio Department of Natural Resources. Statewide, the number was down slightly compared to 2017, when there were 311 incidents. As of June 30 of this year, there were 136 incidents.

Robert McHale, Northeast Environmental Director for MarkWest Energy Partners, walks in to the Humphreys Compressor station with other MarkWest employees. Courtney Hergesheimer | Dispatch photo

In February 2018, workers lost control of a well and an unknown amount of fluid entered a tributary of Captina Creek. People were evacuated as far as a mile away.

Just two years earlier, a brine truck crash resulted in more than 4,000 gallons leaking into the village’s reservoir.

In September 2018, there was a tanker crash which caused 840 gallons of production brine to be released into a nearby creek.

In neighboring Noble County, there have been a couple reported explosions. One, reported in January 2018, “shook the house and flames were above the ridge line an estimated 200 feet,” according to ODNR reports.

“We were scared to death. The noise was horrific — like a jet engine. We were approximately 2 miles over on the next ridge, but we didn’t know that. It sounded and looked like the whole hillside had exploded and was on fire. We never felt safe … after that,” said Kerri Bond, who has since moved.

Belmont County Commissioner J.P. Dutton, who lives less than a mile from a well pad with his wife and young children, previously was a policy analyst in the energy industry. He said he believes the wells are safely managed.

“I put full faith in those individuals that spend their day-to-day activities focusing directly on those issues, whether it’s the U.S EPA, the Ohio EPA, the Ohio Department of Natural Resources,” he said. “When concerns come up, we try to direct those (concerned residents) to those individuals who can best answer those questions.”

Like what you’re reading?

Stories that inspire. Coverage that informs. Investigations that affect change.

This is real news just when it’s needed most.