Camp Bragg is born

The man known as the “father of Fort Bragg” said he didn’t set out with a particular destination in mind when he started looking for a place to locate a new field artillery training camp.

Col. Edward P. King told a Fort Bragg historian years after he recommended the site for what is now the nation's largest military installation that he had never so much as heard of Fayetteville when he stopped in the town in June 1918.

But King — who traveled south with an official from the U.S. Forestry Service — liked what he saw in the rolling hills and tall longleaf pines of the Sandhills.

“We liked it so well that we went no further,” he wrote to the historian.

There are conflicting accounts as to why Camp Bragg, as it was initially known, was established in this part of eastern North Carolina. But one thing is clear. The camp, which wouldn’t be completed until after World War I drew to a close, would not have been established were it not for the Great War.

The U.S. Army pre-World War I was small, even by today’s standards. And officials, upon America’s entry into the war in 1917, were quick to begin a massive buildup of the nation’s military might.

By the summer of 1918, tens of thousands of U.S. troops were being sent to Europe each day. To support that training, the Army established dozens of new camps across the country.

Some remain to this day, early versions of what are now known as Fort Jackson in South Carolina, Joint Base Lewis-McChord in Washington and Fort Meade in Maryland.

In North Carolina, three camps would eventually be created, including Camp Bragg, Camp Greene near Charlotte and Camp Polk near Raleigh.

The location of what is now Bragg was chosen as the Army sought out a new artillery training post. King was involved in the search from the start.

The Army wanted a site with adequate water, suitable soil, nearby rail transportation and a climate suitable for year-round training. An initial search in Maryland and Virginia ended empty-handed.

King began a new search with the help of geologist T. Wayland Vaughn.

Highways were nonexistent, King would write years later. The pair did not have road maps. And they found few signposts throughout the country.

“We traveled by the compass and dead reckoning,” he said. “It would be impossible for me to tell you where we went.”

On the fourth day of their journey, King wrote that the pair stopped in the community of Manchester, near what is now present-day Spring Lake.

“We stopped for a bottle of Coca-Cola and asked the shopkeeper where we might stay for the night,” he said. “He directed us to Fayetteville. That was the first time I had ever heard of that town.”

The next day, King and Vaughn examined the site of what is now Fort Bragg. It was the first tract of land that met their requirements.

Officials formally requested the creation of Camp Bragg — named for Mexican War hero Capt. Braxton Bragg, who also served as a Confederate general during the Civil War — in July.

Weeks later, on Sept. 4, 1918, Camp Bragg was officially established by executive order. Construction began 12 days later.

Aug. 21, 1918

The War Department issues General Orders No. 77 establishing Camp Bragg as a field artillery cantonment. That same day, Congress authorizes $14.5 million for the camp, with nearly $1 million used to purchase 50,711 acres in Cumberland and Hoke counties, at an average cost of $18.45 an acre.

Soldiers train on a range in the early days of Fort Bragg, sometime around 1920. [18th Airborne Corps Command Historian Collection]

Sept. 4, 1918

Camp Bragg is officially established by executive order. In the weeks to come, construction begins.

Camp Bragg, now known as Fort Bragg [File photo]

Fayetteville's responsibility

Editor's note: This editorial ran in The Fayetteville Observer on Aug. 7, 1918, shortly after the Army announced it would establish a training camp near Fayetteville.

“Fayetteville is going to have a camp.”

Do the people of this city realize that they have had placed upon them a grave responsibility? Within a few weeks the population will be increased by thousands — men drawn here to work on the construction of a great government undertaking that will necessitate the expenditure of millions of dollars, men with all the virtues and sins, all the strong points and weak points of human beings, men cast in the same mold with ourselves. How are the people of Fayetteville going to measure up to the responsibility that has been placed upon them? What is the thought that is uppermost in the minds of the majority? Is it, “How much money am I going to get out of this great and sudden change in conditions?” Or is it, “What can I do to assist in adjusting matters so that a stupendous task can be accomplished to the best interests of all?”

It has been conceded by the Army officers who have gone over the camp site selected in the vicinity that it is well adapted to the purpose for which it will be used — in fact, that it is ideal. Are we glad that a camp is to be placed on it because it will be good for the young men of the country who are to be trained as soldiers? Are we thinking of the best interests of the government and the country in connection with the camp proposition or do prospects of gain and the raking in of money crowd out all other consideration?

There rests on every man and woman in Fayetteville today a share of responsibility in solving the great problem of the camp. The fact that an individual did not favor getting the camp does not relieve him from the responsibility, either. We cannot pick and choose our burdens; we should take them up as they are thrust upon us. If Fayetteville as a community looks on the camp simply as a money-making opportunity and shapes its course accordingly, the camp is going to be an unmixed evil. If, on the other hand, Fayetteville as a community takes up the camp burden in a spirit of patriotism and a realization of its duty and responsibility, the camp will be beneficial not only to this city and section, but to the whole country.

The first thing that Fayetteville should be busy about is providing means to house and care for the great influx of people, and to care for them at live and let live prices. The next thing should be to make conditions such that Fayetteville shall be talked of as a good town to visit or work in or dwell in, and not a town in which the skin game is played to perfection.

In the meantime, Fayetteville should remember the fable of the old woman who killed the goose that laid the golden egg. The opportunities to make money are going to be numerous, but it is easy to overdo the thing, and Uncle Sam may perhaps be taking notes and bringing matters to a sudden halt when all seems to be going well.

Feb. 8, 1919

Men and material from Camp McClellan, Alabama, arrive at the camp. They include artillery forces, the 32nd Balloon Company, the 84th Photographic Section, the 25th Radio Detachment and one air squadron.

April 1, 1919

The airfield at Camp Bragg is renamed Pope Field in honor of 1st Lt. Harley H. Pope, who was killed in a crash near Fayetteville. Pope, flying from South Carolina, crashed after being unable to locate his landing field. He died while attempting to land in the Cape Fear River.

Harley H. Pope, aviator for whom Pope AFB was named. [File photo]

May 24, 1919

Initial construction of the camp ends. Camp Bragg’s population includes 536 officers, 15,713 enlisted men, 51 nurses and 5,780 animals.

The 276th Aero Squadron in 1919 at Pope Field on Fort Bragg. [18th Airborne Corps Command Historian Collection]

The savior of Fort Bragg

Camp Bragg was still a fledgling Army post when Brig. Gen. Albert Bowley arrived to command it in July of 1921.

But Bowley liked what he saw. And he fought for its survival.

Bowley, who commanded Bragg from 1921 until March 1928, oversaw what is perhaps the most tumultuous era in the post’s 100-year history.

Shortly after taking command, the War Department ordered Camp Bragg abandoned and its troops sent to Camp Knox, Kentucky. But Bowley disagreed.

By the time he left command, Camp Bragg would be rechristened Fort Bragg. And the groundwork would be laid for the post to play a key role in the next world war.

Elizabeth Coble, the 18th Airborne Corps command historian, said the general was impressed with Bragg from his arrival.

“He was amazed when he got here at how large the land mass was and how much had been built quickly,” she said. “Bowley recognized what an asset it was. And he saved it.”

In a letter to his sister, Bowley described his efforts as "a grand opportunity to play politics both Army and civil and win out."

He schemed with North Carolina Republicans, made deals with local press and convinced local leaders to stay largely on the sidelines of the efforts to save the post. More importantly, he secured a visit from Secretary of War John W. Weeks.

Bowley enlisted volunteers from Fayetteville who planted trees and created gardens. He scouted routes on post for a tour and ordered road repairs, trees trimmed and water crossings fixed.

Once Weeks arrived, Bowley wined and dined him, all the while extolling the virtues of the post. That night, with maps spread across the dining table, Bowley made his final plea.

“It was a hard fight,” Bowley later recalled. “Bragg kept slipping father and father away.”

On Sept. 14, 1921, weeks after reporting on Bragg’s demise, The Fayetteville Observer recreated a telegram from Bowley on its front page.

“Camp Bragg wins. Everything satisfactory. Your suburb permanent. Gruber and School return. I remain your neighbor. Congratulations.”

Aug. 23, 1921

The War Department orders Camp Bragg abandoned and sends its remaining forces to Camp Knox, Kentucky. Since 1920, the camp had been steadily losing troops as the country demobilized from World War I.

Sept. 14, 1921.

A headline on the front page of The Fayetteville Observer announces that Camp Bragg has been spared and will become permanent, thanks to the efforts of Brig. Gen. Albert Bowley, then post commander.

General Albert Bowley [File photo]

April 1922

Annie Oakley appears at Camp Bragg to challenge the camp’s sharpshooter to a rifle and pistol match. It is unclear who won.

A photo of Annie Oakley, who spent time in Pinehurst during the 1920s, is displayed at the Tufts Archives inside the Given Memorial Library in Pinehurst. [Johnny Horne/The Fayetteville Obsever]

The early years

Camp Bragg was officially established in September 1918. The early troops included artillery forces, a balloon company and an air squadron. By the early 1920s the name had been changed to Fort Bragg.

Soldiers stand on a large artillery gun on Fort Bragg in the 1930s. [18th Airborne Corps Command Historian Collection]

Sept. 9, 1922

The name of the camp officially changes to Fort Bragg.

July 4, 1923

Fort Bragg hosts the first of many parachute jumps at what will become the “Home of the Airborne.” Artillery observation balloons are used as jump platforms and large crowds gather to watch the exhibition.

March 11, 1925

A fire burns nearly 90,000 acres on Fort Bragg. More than 500 men gather to fight the blaze and soldiers work in 24-hour shifts until the fire is put out on March 16.

Nov. 12, 1926

Officials announce the rebuilding of Fort Bragg, replacing much of its early, temporary buildings with permanent structures.

An aerial view of Fort Bragg in 1929. [18th Airborne Corps Command Historian Collection]

Fort Bragg trained airborne troops during WWII

Fort Bragg's history as "Home of the Airborne" started 10 months after the United States entered World War II in the fall of 1942, local historian Roy Parker Jr. wrote in his Military History column for The Fayetteville Observer.

That was when the paratroopers of the newly minted 82nd Airborne Division and their counterparts in the 101st Airborne Division began arriving here from Camp Claiborne in Louisiana, the late Parker wrote in June 2004. The Army trained all five of its airborne divisions — the 82nd, 101st, 11th, 13th and 17th — at Bragg or nearby Camp Mackall during the war.

"The primary mission of Fort Bragg during the war was training airborne troops," said Kenneth J. "Rock" Merritt, who jumped into Normandy with the 508th Parachute Infantry Regiment and went on to twice become command sergeant major of the 18th Airborne Corps and Fort Bragg.

Merritt, who lives in Fayetteville, trained for advanced infantry and airborne operations at Camp Mackall.

"Out of five airborne divisions," the 95-year-old D-Day veteran said, "four of them seen combat. The only one that didn't was the 13th Airborne, which was at Fort Bragg when the war ended."

Merritt was quick to respond when asked if Fort Bragg's contributions proved vital to the Allies' cause and, ultimately, their winning the global war.

"Oh, hell yeah. Without a shadow of the doubt. Look at the leaders they had. All those lieutenants and captains under Gen. Lee," he replied, citing eventual Lt. Gen. Robert F. Sink and Lt. Gen. James Gavin among them. "Yeah, Fort Bragg was very instrumental. If you had asked Gen. Lee, he would probably have said without those three airborne divisions, they would have pushed the (seaborne) 4th Infantry Division back into the English Channel (from the Normandy beaches). That's what Lee told the president of the United States."

July 1939

The Army reveals one of its newest weapons, the 155mm howitzer, at Fort Bragg. The howitzer is tested at Bragg before being fielded across the Army. At the time, it’s the most powerful field gun in the force.

Nov. 16, 1940

The 9th Infantry Division holds its first division review at Fort Bragg. To celebrate, the post commander orders that hot water be available at post bath houses that week.

Dec. 4, 1940

The first trainees inducted into the Army at Fort Bragg under the Selective Service Act arrive. By 1945, more than 300,000 draftees are processed on post, with 135,000 of them rejected from military service.

Training at Airborne Command at Fort Bragg during World War II. [U.S. Army photo]

1940 - 1941

As the nation prepares for World War II, construction on Fort Bragg booms. At its peak, one building is completed every 32 minutes, and more than 30,000 men are employed to expand the post.

Jan. 1, 1941

The troop population at Fort Bragg reaches 20,000 soldiers for the first time. By July, the post is home to 67,000 men, and Fort Bragg is the largest Army post in the U.S.

A group shot of Fort Bragg construction workers on March 20, 1941. [18th Airborne Corps Command Historian Collection]

Feb. 1941

A 1,680-bed hospital, the largest in the Army at the time, opens at Fort Bragg. The hospital is temporarily heated by steam from a locomotive until a central heating plant is completed.

WWII brings growth to Bragg

As the nation prepared for World War II, construction on Fort Bragg boomed and the troop population surged. In 1942, the 82nd Airborne Division moved to Fort Bragg.

Soldiers with Company J, 41st Engineer Regiment conduct a gas mask drill in March 1942 at Fort Bragg. [Library of Congress]

June 3, 1942

The 6th Field Artillery stages its final horse-drawn review. Subsequent artillery units are motorized.

Aug. 15, 1942

The 82nd Airborne Division, the nation’s first airborne division, moves to Fort Bragg. In October, it is joined by the 101st Airborne Division. Eventually, all five airborne divisions train at Bragg or nearby Camp Mackall.

Paratroopers with the 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion sit in the belly of a transport plane for a jump at Camp Mackall in the 1940s. [18th Airborne Corps Command Historian Collection]

Jan. 24, 1943

The 37th Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps arrives at Fort Bragg. It’s the first WAAC unit on post and its members take up numerous non-combatant duties across Fort Bragg.

1945

As World War II draws to a close, Fort Bragg is one of 17 military installations set up to discharge service members returning from the war.

Sept. 18, 1947

Pope Field becomes Pope Air Force Base with the creation of the U.S. Air Force.

Fort Bragg plays big role in controversial war

The war in Vietnam remains one of the most controversial conflicts in the nation's history.

And Fort Bragg had a starring role, hosting new trainees and being home for the seasoned Special Forces soldiers who played an integral part in the war effort.

The most decorated forces hailed from the Special Forces community, which helped train, equip, organize and lead indigenous guerilla forces and South Vietnamese troops against the Viet Cong.

At the height of the war, more than 200 Special Forces teams, most from the 5th Special Forces Group, operated alongside a force of 50,000 guerilla fighters.

Among the conventional forces in Vietnam, the 82nd Airborne Division was left on the sidelines for most of the war.

The exception came in 1968, when the division's 3rd Brigade, nicknamed the "Golden Brigade," was called to action and deployed on short notice.

After North Vietnamese and Viet Cong forces had launched the Tet Offensive in a surprise attack on Jan. 30, 1968, officials requested that additional combat forces be immediately deployed.

The 3rd Brigade arrived in Vietnam within weeks and operated in the area around Hue, Phu Bai and Da Nang.

Paratroopers formed teams to patrol at night, cleared roads of landmines each morning and aggressively set ambushes for enemy troops. Nearly 230 soldiers from the unit lost their lives during the 22 months the unit spent in Vietnam.

As the war raged overseas, Fort Bragg and Fayetteville also gained attention on the homefront as the site of numerous protests, some including celebrities.

In September 1969, GIs United Against the Vietnam War protested Fort Bragg’s ban of its newspaper “Bragg Briefs.”

Weeks later, about 400 people joined a peace parade in downtown Fayetteville. And in May 1970, 2,000 protesters gathered in Rowan Park for an anti-war rally featuring actress Jane Fonda. Fonda also was kicked off Fort Bragg while trying to hand out leaflets related to the protests.

Fonda would return to Fayetteville again and again before the war's end, starring in anti-war theater shows.

May 21, 1951

The 18th Airborne Corps is reactivated at Fort Bragg.

April 10, 1952

The Psychological Warfare Center is established at Fort Bragg and is tasked with supervising training in psychological warfare and Special Forces, to develop and test doctrine and to test and evaluate special equipment.

Students sit in booths, wearing earphones, as they receive language instruction at the Special Warfare Center at Fort Bragg on Sept. 29, 1964. The center trains soldiers in counterinsurgency psychological operations and special warfare to replace the old-fashioned, command-type soldier. The language school teaches everything from Swahili to Burmese in many dialects. [AP Photo]

January 1957

The 82nd Airborne Division War Memorial Museum opens on Fort Bragg.

September 1961

A 15-foot statue honoring paratroopers, Iron Mike, is unveiled at Bragg Boulevard and Knox Street on Fort Bragg.

The "Iron Mike" statue is moved along Butner Road in June 1979. [Dick Blount/The Fayetteville Observer]

Sept. 21, 1961

The 5th Special Forces Group is activated at Fort Bragg. Its soldiers play a key role in the war in Vietnam.

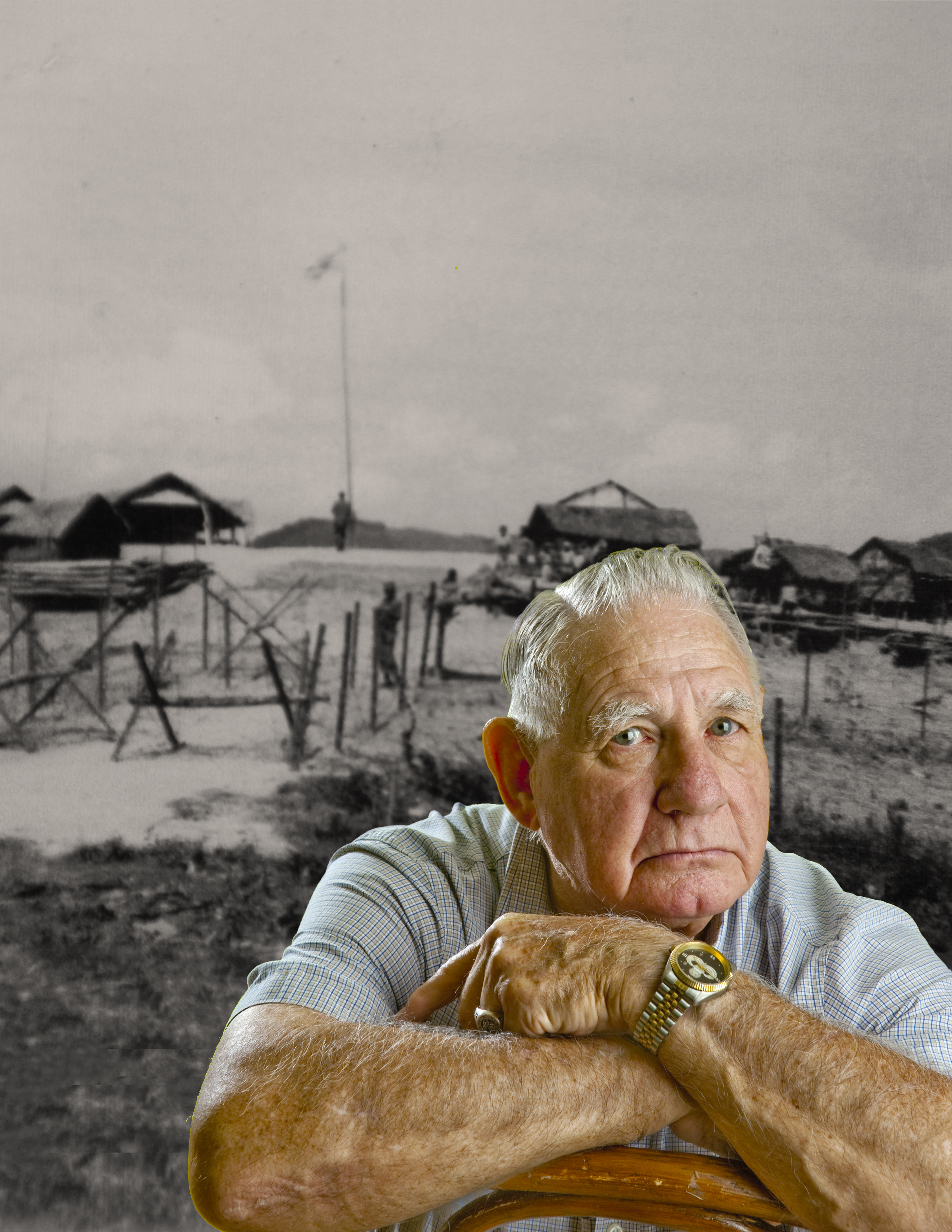

Jake Roth served over in Vietnam in two tours with 5th Special Forces Group. [Raul R. Rubiera/The Fayetteville Observer]

The Cold War

During the struggle between East and West after World War II, Fort Bragg remained strong as it saw growth in psychological and special operations units.

President Harry Truman stands at attention as the post band at Fort Bragg plays the national anthem shortly after his arrival to watch the 82nd Airborne Division put on a secret demonstration of postwar field artillery developments on Oct. 4, 1949. At left rear is Gov. W. Kerr Scott and at right is Lt. Gen. John Hodge, the Fort Bragg commander. [AP Photo]

November 1962

Fort Bragg Special Forces soldiers participate in the funeral of President John F. Kennedy. Forty-six local soldiers take part in ceremonies in Washington D.C.

March 1964

Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara announces the Special Warfare Center has been renamed the U.S. Army John F. Kennedy Center for Special Warfare. It later settles on its current name, the U.S. Army John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center and School.

President John F. Kennedy speaks to Brig. Gen. William P. Yarborough during Kennedy's visit to Fort Bragg on Oct. 12, 1961. [Cecil Stoughton/White House Photographs]

1964

The U.S. Army Parachute Team, the Golden Knights, host the first all-service parachute meet at Fort Bragg.

Dec. 5, 1964

Capt. Hugh Donlon, a Fort Bragg soldier assigned to the 7th Special Forces Group, is the first soldier awarded the Medal of Honor for valorous actions in Vietnam. The award is presented by President Lyndon B. Johnson.

The home of special operations

From the earliest days of the nation’s history, troops have formed elite units that have spearheaded conflicts dating to the Revolutionary War.

Fort Bragg’s role as home to many of those forces, however, did not begin until after World War II.

Today, the nation’s largest military installation is also home to U.S. Army Special Operations Command and Joint Special Operations Command.

The nation’s active-duty civil affairs and psychological operations troops all call Fort Bragg home, as does the headquarters for Special Forces and a large portion of the Air Force’s Special Tactics airmen.

Civil Affairs and psychological operations soldiers can trace their history back 100 years. And this year, as Fort Bragg celebrates its centennial, those soldiers also are celebrating a century of service.

Other modern day special operations forces trace their history to the Office of Strategic Services during World War II, which was formed to gather intelligence and conduct operations behind enemy lines in support of resistance groups in Europe and Burma, or to the First Special Service Force, an elite Canadian-American unit that fought in North Africa, Italy and Southern France.

Many OSS veterans would lead the Army’s fledgling special operations community years later as the unconventional warfare mission took on a greater role within the military.

U.S. Army Special Forces Command, now the 1st Special Forces Command, was created in 1952, the same year as the nation’s first Special Forces group.

That same year, the Psychological Warfare School was established at Fort Bragg. Today, it is the John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center and School.

Special Forces soldiers first saw combat in Korea in 1953. They would play a central role in the nation’s efforts in Vietnam more than a decade later. And, in more recent history, they would be the first soldiers to deploy to Afghanistan and play an instrumental role in that fight.

President Kennedy remains one of history’s chief advocates for Special Forces, also known as Green Berets.

Kennedy endorsed the unique headgear during a visit to Fort Bragg in 1961. And Special Forces soldiers took part in his funeral procession a few short years later.

Today, special operations soldiers remain a key part of the nation’s defense strategy.

U.S. Army Special Operations Command has 33,000 troops and, on any given day, thousands of them are deployed across the globe, often in secretive or austere conditions battling extremist organizations or working with partner nations.

Jan. 30, 1966

A Fort Bragg soldier, Staff Sgt. Barry Sadler, appears on "The Ed Sullivan Show'' to sing an original song, “The Ballad of the Green Berets.” In April, John Wayne visits Fort Bragg in preparation for the 1968 film, “The Green Berets.”

July 1967

The 18th Airborne Corps and a brigade from the 82nd Airborne Division are ordered to Detroit as part of a peacekeeping force in response to riots in the city. In October of the same year, Bragg troops deploy to Washington to counter a Vietnam antiwar demonstration.

Feb. 12, 1968

The 3rd Brigade, 82nd Airborne Division deploys on short notice to Vietnam in response to the Tet Offensive. The soldiers serve 22 months in the country before their return.

April 1968

Local paratroopers deploy to Washington following the death of Martin Luther King Jr. to keep peace in the city and protect government buildings.

May 1970

Actress Jane Fonda leads anti-war protestors onto Fort Bragg and attempts to hand out leaflets before being escorted off post by military police.

April 1980

Soldiers involved in Operation Eagle Claw, the aborted rescue attempt of 52 American hostages held in Iran, return to Fort Bragg.

Fort Bragg troops respond at home and abroad

An Army paratrooper high-fives a returning comrade on Ardennes Street on Fort Bragg in November 1983. The troops were returning from Grenada. [File photo]

There's a popular saying on Fort Bragg, often brought up by visiting dignitaries or in the speeches of the installation's top leaders.

"When the nation calls 9-1-1," they say, "a phone rings at Fort Bragg."

There's truth behind the cliche.

Born as an artillery training installation and now home to airborne and special operations forces, Fort Bragg has evolved into the home of many of the nation's quick reaction forces.

That includes elite special operations forces, the famed 82nd Airborne Division and the 18th Airborne Corps, which is known as "American's Contingency Corps."

Local units train to rapidly deploy anywhere in the world on short notice. And for decades, they have repeatedly answered the nation's call, operating in nearly every corner of the globe. That includes combat deployments to Latin America, Asia and the Middle East, as well as humanitarian relief missions at home and abroad.

October 1983

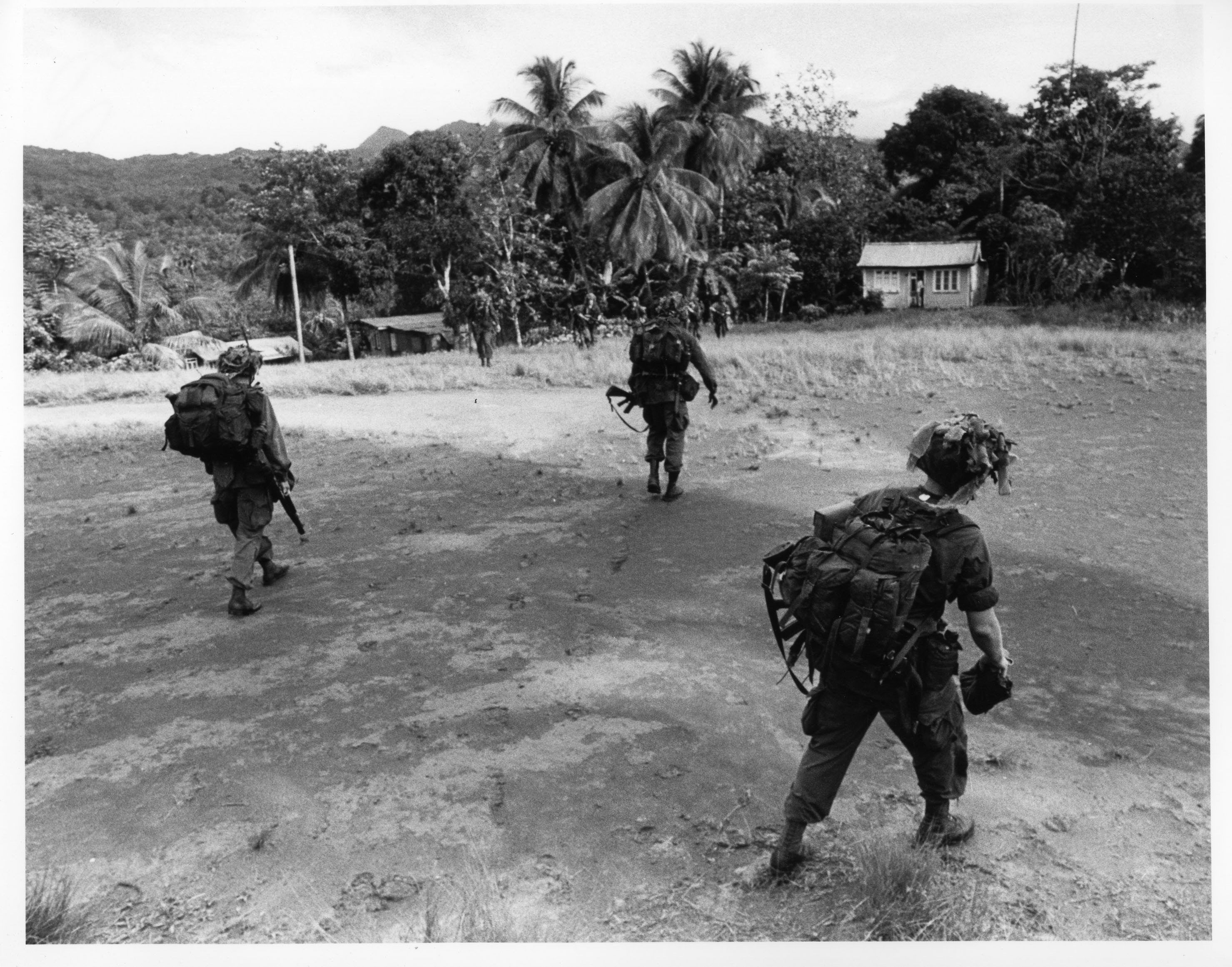

After a coup in Grenada, the 82nd Airborne Division, special operations forces and 18th Airborne Corps are called to deploy to the Caribbean nation to rescue American students and oust the revolutionary government that had seized power. The 51-day conflict is known as Operation Urgent Fury.

82nd troops in Grenada in November 1983. [File photo]

Dec. 20, 1989

The 82nd Airborne Division conducts its first combat jump since World War II as part of Operation Just Cause, which ousts dictator Manuel Noriega from power in Panama.

Aug. 6, 1990

Four days after Iraqi forces invade Kuwait, Fort Bragg soldiers are among the first to arrive in nearby Saudi Arabia. Months later, they are among the first U.S. troops to push into Kuwait and Iraq as Operation Desert Storm begins.

Aug. 28, 1992

The 82nd Airborne Division deploys troops to South Florida in the aftermath of Hurricane Andrew. The paratroopers provide food, shelter and medical attention to those affected by the devastating storm.

A Blackhawk helicopter hovers over two members of the 49th Quartermaster Detachment from Fort Bragg as they attach a sling to it, carrying supplies for victims of Hurricane Andrew on Sept. 11, 1992, at the Homestead Humanitarian Depot. [AP Photo/Kathy Willens]

Oct. 27, 1995

Sgt. William J. Kreutzer opens fire on about 1,300 paratroopers lined up for a run at Towle Stadium at Fort Bragg. Maj. Stephen Mark Badger is killed and 18 other soldiers are injured.

Aug. 16, 2000

The Airborne & Special Operations Museum opens in downtown Fayetteville.

Veterans Day parade goers watch the passing parade in front of the Airborne & Special Operations Museum on Hay Street on Nov. 8 2003. [Steve Herbert/The Fayetteville Observer]

9/11 set a new course for Fort Bragg troops

Not everything changed overnight.

But at Fort Bragg, as for much of the nation, the course of history was forever altered by the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks.

The attacks killed thousands of people in New York, Washington and Pennsylvania.

In the immediate aftermath, Fort Bragg tightened security to its highest level. Training, typically a year-round affair, stopped as soldiers and airmen were readied to respond to the attacks, or it continued with new purpose and urgency.

Fort Bragg soldiers were among the earliest to deploy in support of the war in Afghanistan. In 2003, they would do the same for Iraq.

To this day, local troops remain engaged in those countries, as well as in Syria and parts of Africa, as the fight against global terrorist threats remains.

Retired Gen. Daniel B. Allyn, who most recently served as vice chief of staff of the Army, highlighted Fort Bragg’s role in a post-9/11 world during a remembrance ceremony last year.

“We know the cost and sacrifices of serving a nation at war,” he said. “For 16 years, we’ve been constantly engaged, committed and on point for our nation.”

At the wars’ peak, tens of thousands of Fort Bragg soldiers were deployed. The rotations of troops were a near constant effort, with countless soldiers and airmen deploying to and from Green Ramp at Pope Field.

Today, the deployments have slowed. But they haven’t stopped as Fort Bragg troops continue to support the Global War on Terror.

In the past year, soldiers have returned from Iraq, Syria and Afghanistan. Others are constantly rotating to parts of Africa and the Middle East.

The 18th Airborne Corps, which has repeatedly deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan, will soon once again lead the war against the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria.

The world changed nearly 17 years ago, when the first plane flew into the World Trade Center. And Fort Bragg troops have been in the center of that change.

Sept. 11, 2001

After terrorist attacks kill thousands in New York, Washington and Pennsylvania, security at Fort Bragg is heightened. In the coming weeks, the first soldiers from post deploy to Afghanistan in response to the attacks.

March 20, 2003

The war in Iraq begins. At its start, more than 22,000 Fort Bragg troops are deployed there or in Afghanistan.

Soldiers from the 620th Corps Support Battalion, 1st Corps Support Command at Fort Bragg, stationed at Spring Lake Logistical Support Area, Camp Taqqadum, Iraq. [U.S. Army photo by Pfc. Matthew Clifton]

Sept. 3, 2005

The first of approximately 5,000 Fort Bragg paratroopers arrive in Louisiana in response to deadly floods caused by Hurricane Katrina. The soldiers perform search-and-rescue missions, provide medical care and help keep the peace.

A convoy of trucks head out from Fort Bragg on their way to the Gulf Coast to aid in the relief efforts of the areas affected by Hurricane Katrina. About 200 soliders and 83 vehicles made their way from Fort Bragg to New Orleans on Sept. 7, 2005. [Andrew Craft/The Fayetteveille Observer]

Global War on Terror

Since 9/11, Fort Bragg troops have been steadily serving overseas in support of the Global War on Terror. Green Ramp has been the backdrop for deployments and ceremonies that welcome troops home.

Special Forces hopefuls take part in PT at Camp Mackall on April 29, 2005. [Mike Spencer/The Fayetteville Observer]

Jan. 17, 2010

Fort Bragg troops arrive in Haiti following an earthquake that ravaged the island.

October 2010

Soldiers and staff from U.S. Army Forces Command begin to arrive at Fort Bragg after moving from Fort McPherson, Georgia, as the result of base realignment and closure.

U.S. Army Forces Command/U.S. Army Reserve Command Headquarters at Fort Bragg on Aug. 3, 2010. [U.S. Army photo by Jim Hinnant]

Feb. 28, 2011

Pope Air Force Base becomes Pope Field after it is absorbed back into Fort Bragg as part of the military's base realignment and closure.

'It was a ghost town around here.'

Desert Shield/Storm deployments emptied Fort Bragg and left Fayetteville without many of its residents

Elsie Lampman, employee of "Artshirts" Plaque and Trophy Shop, closed up the shop on Yadkin Road early in fall 1991. The business hours were cut back due to Fort Bragg soldiers being deployed to Saudi Arabia before the Gulf War. [Marcus Castro/The Fayetteville Observer]

Larry Lee hasn’t forgotten how much his business suffered when an estimated 32,000 Fort Bragg soldiers deployed at almost the same time in support of operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm.

“It was a ghost town around here,” said Lee, who has owned Tar Heel Furniture Gallery on North Reilly Road since 1974. “You could go anywhere without any traffic.

“You had to be pretty strong to make it through those times.”

Operation Desert Shield began shortly after Aug. 2, 1990, the day Iraqi forces invaded neighboring Kuwait.

The United States responded quickly, amassing what would become 500,000 troops in Saudi Arabia. The first to arrive: Fort Bragg’s 82nd Airborne Division, the Army paratroopers known for their ability to respond to any conflict in the world within 18 hours notice. By Aug. 24, 1990, more than 12,000 paratroopers had been deployed overseas.

It didn’t take long for Lee and other business owners to feel their loss.

Not only did 32,000 soldiers head overseas, many of their families decided they would rather go home than wait out the war.

The loss of so many people crippled much of Fayetteville, which back then was more dependent on the Army post.

Retail sales dropped 7.3 percent; unemployment went from 3.5 percent to as high as 6 percent; bankruptcies increased 35.7 percent; home sales plummeted more than 30 percent; and car sales fell 22.4 percent.

Lee said business at his furniture store, which is only a few miles from Fort Bragg, fell by as much as 40 percent.

Mike Pate’s business, the Reilly Road Farmer’s Market, fared a little better. Pate, who has owned the store for 37 years, estimated that he lost 20 percent of his customers.

“It could have been a lot worse,” said Pate, who had to rebuild after a tornado destroyed the farmer’s market in 2011.

Fortunately for Fayetteville’s business owners and the soldiers overseas, the first Gulf War wouldn’t last long.

When all of the forces were in place, President George H.W. Bush gave Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein an ultimatum: pull your troops out of Kuwait by Jan. 15, 1991, or face a full-scale attack by the largest buildup of multinational forces since World War II.

Saddam responded by promising “the mother of all battles,” and his forces began lobbing scud missiles into Saudi Arabia and neighboring countries.

Back home, although stung by the growing economic problems, Fayetteville residents displayed a sense of patriotism like nowhere else. As protests against the impending war broke out in Chapel Hill and Asheville, Fayetteville residents planted American flags in their yards and tied yellow ribbons around their trees.

Coalition forces mounted an air attack on Jan. 17. A month later, on Feb. 24, Bush ordered an all-out ground attack, quickly and easily putting Iraqi forces on the run. Americans watched Operation Desert Storm unfold on their TVs, which repeatedly showed smart bombs hitting their targets with precision.

The ground war lasted only four days before Bush ordered a cease fire. Operation Desert Storm became known as the 100-hours war.

Troops began coming home to Fort Bragg the following month.

“They had a pocket full of money when they came back,” Lee said.

Pate and Lee said their businesses quickly rebounded.

Fort Bragg hasn’t experienced a mass-exodus of soldiers and spouses on such a level since then. Although the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan have at times strained Fayetteville’s economy, they have been nothing like what the city saw in Desert Shield and Desert Storm.

One reason for that is Fort Bragg beefed up its community services programs, making it easier for spouses and their families to remain in Fayetteville, said Tom McCollum, a Fort Bragg spokesman. The Army also began an effort to hire spouses, McCollum said.

May 4, 2014

Fayetteville and Fort Bragg host the first All American Marathon, attracting thousands of runners along a course that spans the city and post.

Masashi Shirotake of Charlotte won the All-American Marathon on May 4, 2014. He finished with a final time of 2 hours, 30 minutes and 32 seconds. [Ashley Cross/The Fayetteville Observer]

October 2015

The 3rd Expeditionary Sustainment Command moves to Fort Bragg from Fort Knox, Kentucky.

July 3, 2016

The Miami Marlins and Atlanta Braves play a first-of-its-kind MLB game on Fort Bragg on a temporary field that is later converted for recreational softball.

The press box at the Fort Bragg Game with the Atlanta Braves and Miami Marlins on July 3, 2016. [Shannon Millard/The Fayetteville Observer]

Sept. 18, 2016

The 440th Airlift Wing of the Air Force Reserve furls its colors at Pope Field, officially marking the end of the last Air Force unit based at Fort Bragg with planes.

Officials bid farewell to the 440th Airlift Wing in an inactivation ceremony on Pope Field on Sept. 18, 2016. [Michelle Bir/The Fayetteville Observer]

Aug. 8, 2017

The 1st Theater Sustainment Command cases its colors and moves from Fort Bragg to Fort Knox, Kentucky, ending decades of history on the installation.

Members with 1st Theater Sustainment Command color guard stand at attention March 3, 2017, before the start of the assumption of responsibility ceremony for Command Sgt. Maj. Jason P. Willett. [Shane Dunlap/The Fayetteville Observer]

Oct. 4, 2017

Four soldiers with the 3rd Special Forces Group are killed in Niger during an operation with partner forces in that country. The deaths of Staff Sgt. Dustin M. Wright, Staff Sgt. Bryan C. Black, Staff Sgt. Jeremiah W. Johnson and Sgt. La David T. Johnson mark the deadliest day for deployed Bragg troops since July 14, 2010, when seven soldiers were killed in Afghanistan.

From left to right, Staff Sgt. Bryan c. Black, Staff Sgt. Jeremiah W. Johnson, Sgt. La David Johnson, Staff Sgt. Dustin M. Wright [Contributed]

Nov. 3, 2017

A military judge at Fort Bragg sentences Bowe Bergdahl to a dishonorable discharge, a demotion in rank to E1 and the forfeiture of $1,000 of pay a month for 10 months. Bergdahl was held as a prisoner in Afghanistan for nearly five years after walking away from his unit in 2009.

Sgt. Bowe Bergdahl, right, leaves the Fort Bragg courtroom facility while judge Jeffrey Nance continues to deliberate Nov. 3, 2017, on Fort Bragg. Bergdahl, who walked off his base in Afghanistan in 2009 and was held by the Taliban for five years, pleaded guilty to desertion and misbehavior before the enemy. [Andrew Craft/The Fayetteville Observer]

Dec. 8, 2017

The Army announces that Fort Bragg will be the home of its second Security Force Assistance Brigade, which is trained to advise and assist partner nations in combat.

May 18, 2018

The Army announces a new one-star command, the Security Force Assistance Command, to oversee its new SFABs. The command will be headquartered at Fort Bragg.

A new one-star command will be established at Fort Bragg to oversee the Army’s new Security Force Assistance Brigades. This is their patch. [Contributed photo]