Hero

Content

Should your kid play football?

Introduction The Documentary The Podcast The Tuscaloosa News survey Football in society The medical evidence Participation The economics of football Benefits and perils Life without footballTo play or not to play

Tommy Deas | Executive Sports Editor

Should your kid play football?

It is a question that might have been unthinkable to many just a few years ago.

Football is part of our culture. More than half a century ago, it supplanted baseball as the American pastime. Upward of 100 million people — about a third of the population — watch the Super Bowl each year.

Around here, it is more than just sport and entertainment. Some have likened it to a religion. Without question, it is an important part of the fabric of society.

Increasingly, however, the sport has come under fire. Almost every day it seems a new study is released linking football to brain trauma. It is responsible for more injuries than any other sport at the high school level. Participation in high school football is steadily dropping nationally.

So parents are facing the question of whether they should let their children play.

The Tuscaloosa News delved into that issue, undertaking a thorough examination of the game’s dangers and benefits. There is no clear answer, but it is abundantly apparent that parents need to educate themselves about the risks and rewards before making a decision.

A survey by The Tuscaloosa News found that more than 25 percent of respondents would not let their children play high school football. Proponents cited positives that come from playing, while others enumerated the perils.

The movie “Concussion,” released in 2015, raised awareness of chronic traumatic encephalopathy, a medical condition of brain deterioration better known as CTE, which has been found to be prevalent in former National Football League players as well as some who played at lower levels.

“If you classify your sports based on the amount of contact or collision, football is way up there,” said Dr. Jimmy Robinson, medical director and head team physician for the University of Alabama and medical director for the Alabama High School Athletic Association. “The more collision (in) sports you have, the more dangerous it will be.”

The question of football’s viability has become part of a national dialogue. A contestant in last month’s Miss America pageant was asked if full-contact football should be outlawed at the elementary and high school levels. Briana Kinsey, the 24-year-old Miss District of Columbia — a Hoover native who graduated from the University of Alabama in 2015 — came out in favor of abolishing the sport due to its dangers.

Alabama coach Nick Saban, who has won five national championships, including four at UA, disagrees.

“I think football is a great game, it’s the greatest team game of any game that is out there that guys can play,” he said.

The case for football

Advocates cite football’s ability to teach teamwork, discipline, toughness and leadership.

The sport has no better proponent than Saban. What makes it great, according to the coach, is the things it teaches.

“There’s a lot of lessons to be learned in any athletic competition,” he said. “Football, because of the number of participants and the number of ways that people can contribute, I think is a phenomenal way — and it was really good for me growing up — to develop sort of some of the attributes that it takes to be successful, whether it was commitment, hard work, perseverance, ability to overcome adversity, pride in performance.”

Overcoming fear is also part of the game.

“I think as a kid it was more the sound of it that scared you more than the contact,” said Travis Reier, senior analyst at BamaOnline.com, a website that covers Alabama football. “That’s more what I recall from the early days of playing: You could hear it, it makes that sound. It’s indelible, and you know it.”

Getting past that fear had its rewards.

“Just the structure: being on time, doing what you’re supposed to do when you’re supposed to do it,” Reier said. “I was very blessed to have excellent coaches from the earliest levels.

“I don’t like to even think about what might have happened to me as a kid if I didn’t have the football coaches I had. They didn’t ask it from me; they demanded it. They got everything I had, which wasn’t a whole lot, but again, I was on time, I was where I was supposed to be.

“It helped me in school, too. It carried over. I think it was sort of unconsciously, but that regimen that I went through with football, it helped me in school.”

In many ways, football is the sport of opportunity. According to data compiled by the NCAA, it can be a gateway to higher education, with 25 percent of players — the highest percentage of any sport — becoming the first in their families to attend college.

While football has the lowest cumulative grade-point average of any NCAA sport at 2.75, players at the Division I and Division III (non-scholarship) levels graduate at well above the national average at 74 and 75 percent, respectively. Division II players graduate at a 51 percent rate, below the national average of 59 percent cited by the U.S. Department of Education.

Football players at the University of Alabama graduate at an 80 percent rate, according to the latest NCAA report. The average graduation rate for the sport among Southeastern Conference schools is 72.8 percent.

The benefits, however, must be weighed against the dangers. With the mounting medical evidence of football’s association with brain trauma, changes in rules, treatment of injured players and equipment are at the forefront with leaders in the sport.

“I think we will continue to evolve,” said Steve Savarese, executive director of the Alabama High School Athletic Association, who was a longtime football coach before moving into his current position. “Better equipment. Safer game. Even more data. In the computer age, we’ve been able to collect much more data, and that data is the key to us formulating policies and rules for the future, so I think you’ll see an even safer game, because there is such a positive benefit of participating in sports.

“I think it will continue to evolve. I pray that is what it does.”

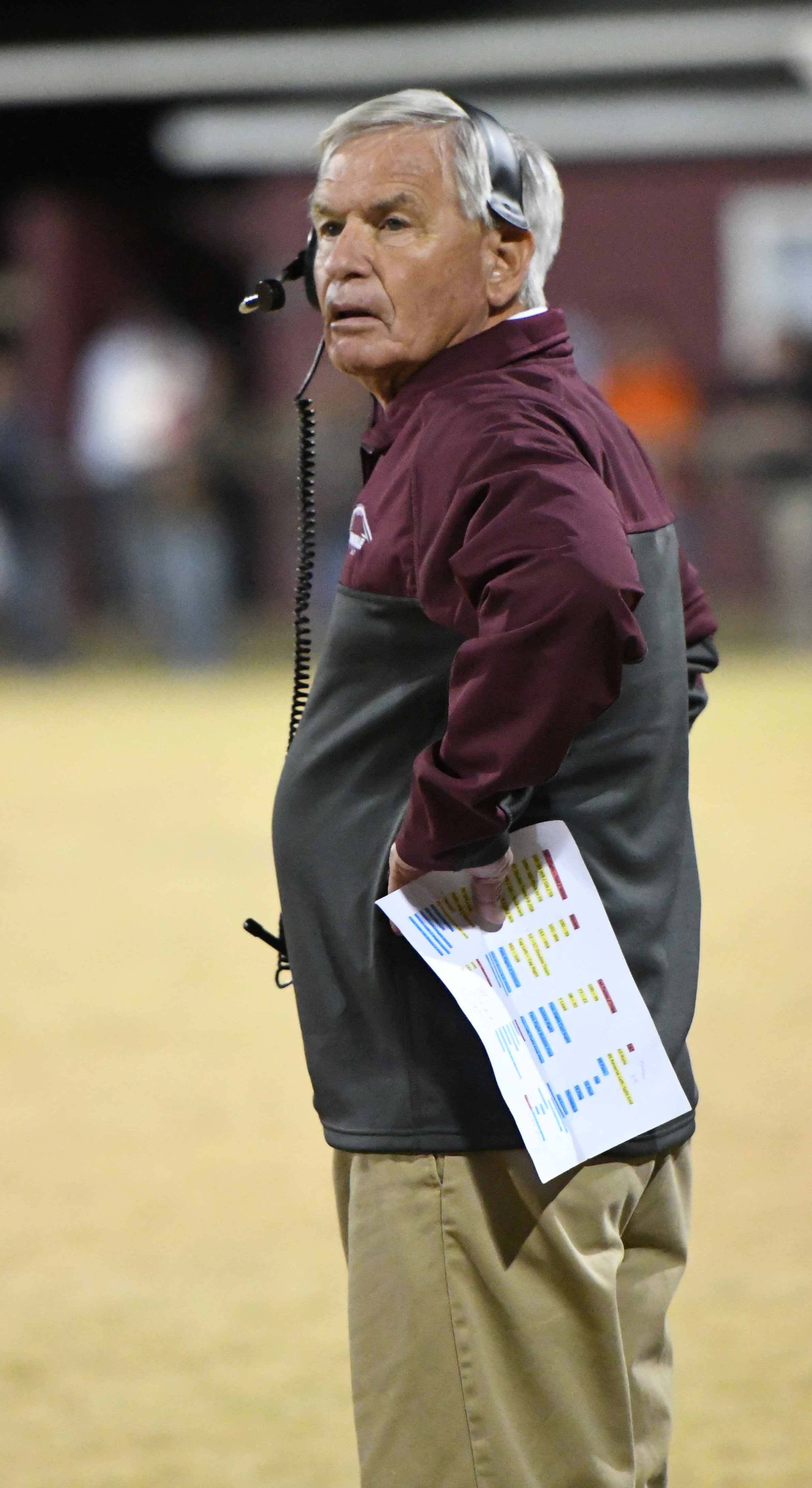

Central High School coach Dennis Conner said he believes players leave the game with better coping skills.

“Football is just like life,” he said. “You are going to get knocked down; you’ve got to get back up. You are going to have bad days, and you’ve still got to fight through that. You are going to have long days, and you’ve got to fight through that. There are days you are going to get up and you are going to be sick.

“You know, football is a parallel of life, and without God and football I don’t know what I would be doing right now.”

The case against football

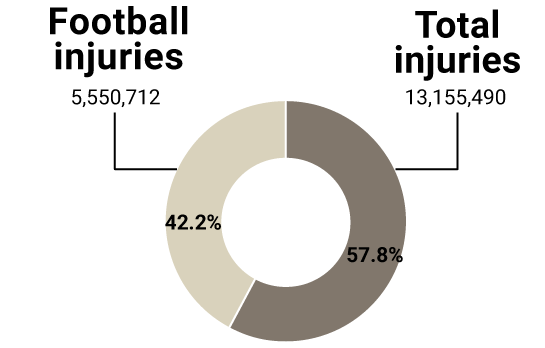

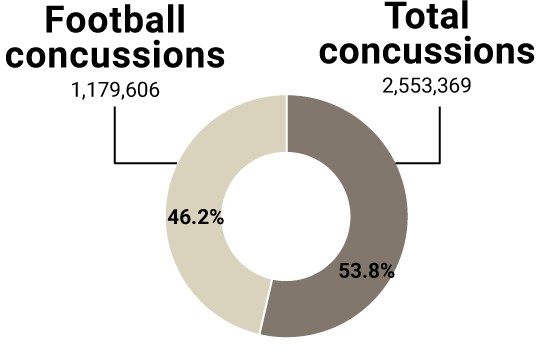

Football critics can point to its high incidence of injury, with more than 42 percent of the injuries sustained by high school athletes in all sports over the last 10 years occurring in football practices or games, according to data compiled for the National Federation of State High School Associations.

Of greater concern, more than 46 percent of concussions sustained by high school athletes come from football.

Bill Curry is a former Alabama head coach who played 10 years in the NFL. After a game in which he sustained a concussion playing for the Green Bay Packers, he had the following exchange with his coach, Vince Lombardi:

“Curry, come here,” the coach said. “Do you know where you are?”

“No, sir.”

“Do you know who you are?”

“No, I don’t,” Curry answered.

“Do you know who won the game?”

“Yes, sir, we did.”

“You’ll be fine,” the coach told him.

Curry doesn’t remember the incident. He knows about it because his wife, who was there, told him.

That’s the way it was in the old days, when a player knocked unconscious might be revived by ammonia capsules and put back on the field.

“All of us have stories like that,” Curry said of his old NFL mates.

Curry has had five shoulder replacement surgeries, a broken nose and a deviated septum that had to be repaired three times. It wasn’t until his ninth year in the pro league — after 10 previous years of high school and college ball — that he sustained what he considered a serious injury, when his knee was “shattered.”

Curry didn’t want his son to play football.

“I got him piano lessons, I got him golf clubs, basketball goals, everything,” the former coach said.

Yet every morning, the son would put on a football helmet. Finally, when he was 10, the child challenged his father: “You’re the coach at Georgia Tech and you’re not going to let me play?”

The younger Curry played through three surgeries, walked on at Virginia and earned a scholarship as a long snapper.

“He had a great experience doing something I didn’t want him to do,” Curry said. “I didn’t want him to get beat up. Now he’s got five boys and they’re playing football.”

Curry says he doesn’t regret playing. Now 75, he recounts lessons he learned from the game that shaped his life. He fondly remembers playing for coaching giants like Lombardi, Bobby Dodd, Don Shula and even Paul W. “Bear” Bryant, Alabama’s legendary coach, for a week at an all-star game.

But he also counts the friends who have suffered from dementia and died.

“Out of the people that played as long as I did, I think maybe I’m the luckiest one,” he said.

North River Christian Academy, a small private school that moved up to 11-man football two seasons ago after previously playing eight-man ball, started the season with 23 players. Due to injuries, the Chargers were down to just 18 healthy players by early October.

In the first month of play, no less than four NRCA players left games via ambulance.

“I think it’s more the parents being more precautious, and there’s absolutely nothing wrong with that,” said Todd Jones, the school’s athletics director. “It’s a good thing. People now are going to a greater extent to making sure the kid is OK.”

The risk of injury is balanced by some parents against the possible reward of earning a scholarship to play in college. The data, however, suggests that may be pursuing fool’s gold: only 5 percent of high school football players in the state are recruited by Division I schools, and only 6.8 percent of all high school players nationally go on to play NCAA football at some level.

A changing game

Football has evolved from an Americanized form of rugby at its beginnings to the more wide-open game we see today.

By the 1950s, offenses concentrated on the running game. Three-yards-and-a-cloud-of-dust attacks were based upon controlling the line of scrimmage by physical blocking in close quarters.

Into the 1950s, substitution rules were strict. Players played both offense and defense, with the same 11 on each team playing the entire game for the most part.

A major rule change in the 1960s allowed offensive linemen to use their hands, improving the ability to better protect the quarterback and opening up the passing game.

Today’s spread offenses utilize the width and depth of the field, with an emphasis on getting the ball into the hands of speedy playmakers in open space. This style of offense creates the ability to make large gains, but it also leads to an increase in hard hits on vulnerable receivers, especially when they run routes across the middle.

More recently, safety rules that outlaw dangerous shots to the head and leading with the helmet have been implemented. A high school rule introduced this year similarly penalizes blind-side blocks.

Practices are less stressful on players, too. Back-to-back days of contact have been legislated out of the high school game, and two-a-day practices have been done away with at the high school and college levels. Long gone are the days when players were denied water breaks during practice to enhance their toughness.

Brutal camps like the one Bryant held in 1954 in Junction, Texas, for his Texas A&M players — including Gene Stallings, a future Alabama head coach — could never happen today.

“Absolutely they’re making the game safer,” said Robinson, the Alabama team physician.

Jones, the athletics director at North River Christian Academy, played in the late 1970s and early ’80s at Holt High School under Woody Clements. He said he believes the game has become softer.

“Coach Clements would do anything in the world, help you with anything you needed done, but when we practiced, we practiced,” Jones said. “We weren’t allowed water bottles and we didn’t have breaks every 20 minutes or what have you. We had 3 seconds, the water would go in your helmet and you’d drink it out of your helmet.

“When it came 5 o’clock, you didn’t leave. You left when practice was over.”

The future of football

What will the game look like in 10 or 20 years? No one knows for sure, but the best answer may come from looking at the past.

“There’s a long history of rules changes, of adapting, of keeping the sport around and not getting rid of it,” said Michael Wood, an American Studies instructor at UA. “So I would see, before football just disappears, efforts made to make it safer.”

On the equipment front, research is ongoing to create helmets that better protect from concussive and sub-concussive blows.

“I don’t necessarily agree that helmet design makes a big difference,” Robinson said. “Helmets were really designed to prevent skull fractures, and some of the newer helmets that are coming out are actually heavier, and especially at the high school or little league level, if the helmet’s heavier, they don’t have the neck muscle control to hold that helmet up. That can be an issue.”

Changing the nature of the sport may be on the horizon. Many high school teams play 7-on-7 football in the offseason, a form of the game with no tackling, blocking or running plays, in keeping with today’s spread offenses. It’s a passing game where a touch below the neck ends a play.

Long ago, Curry asked Tom Landry, the longtime Dallas Cowboys coach, what direction he thought the game would take. Landry told him that he foresaw a move toward a precision passing game.

“That was in the late 1980s, when I was at Alabama,” Curry said, “and that’s exactly what happened.”

Today’s wide-open passing game that has taken hold in the high school, college and NFL ranks seems as distant from the 1950s form of hard-nosed ball as an even less physical form might seem in another decade or two.

A move even further in that direction may be met with resistance from fans.

“The hardest part of that will be convincing the fans who have had over 100 years of football being this violent, kind of masculine, rough sport, convincing them that this is still football,” Wood said.

Should your kid play?

For parents facing the decision of whether to let their kids play, it comes down to weighing the possible hazards against the benefits.

Those contemplating getting their children involved at a young age might consider easing them into it. Many medical experts, Robinson said, advocate not playing tackle ball before they reach high school age.

“Before then, they should play maybe a flag football-type sport where they’re learning the game better,” he said.

The doctor said he would like to see youth football — both the tackle and flag forms — include instruction in fundamentals such as proper tackling techniques, as well as neck-strengthening exercises to build a better muscular support base for the head, and vision training to anticipate big hits before they happen.

“Do that while they’re younger,” he said, “so it becomes natural for them when they’re playing the sport.”

Parents should know what their kids are getting into before allowing them to play.

“There are dangers in football,” said Lamar Harris, who is in his 41st year of coaching at Hubbertville High School. “It is a violent sport. That is what it is. Anytime you come out there, you assume those risks.

“That’s not to say we shouldn’t be as safe as we can possibly be, but it is a sport of hitting.”

Many have made the move to lighter-contact youth ball. Local youth flag football participation is up from 237 players to 475 over the last five years, an increase of more than 100 percent.

Parents should also check out youth coaches before signing up their kids.

“I think that’s the key to everything, and not just in terms of learning to play the right way and safely and all of those things, but just the life lessons I got out of the game,” Reier said.

Jason Bothwell, an assistant coach at Northridge High School, said he sees a lot of young players who haven’t been taught proper fundamentals. They inflict more harm on themselves than their opponents.

Bothwell doesn’t have children, but if he did he’d vet the coaches before letting them play.

“If they’re put in the hands of the right instructors or coaches that can teach them how to formally play the game, to escape injury, I would strongly consider it,” he said. “But just (to let them play) to make a little league coach look good and them not getting what they need to help them sustain their career through high school, then I probably wouldn’t.”

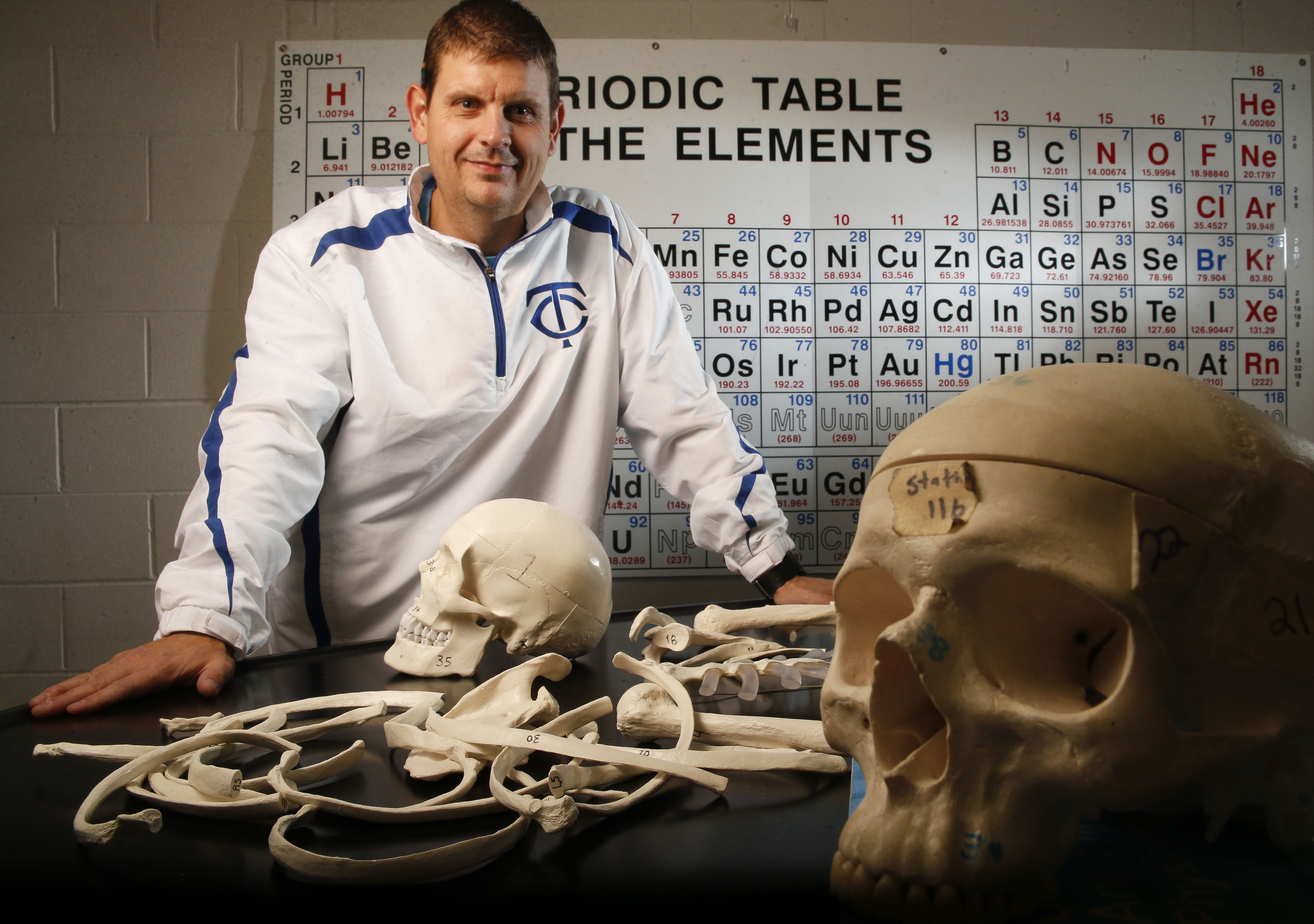

Dr. Tosh Atkins, an orthopedic surgeon, came to his occupation in large part because of his experience with football in the early 1980s at Central High School.

“I broke several fingers and dislocated my thumb,” he said. “I separated my shoulder, and then my senior year I injured my knee and had surgery and missed a few games. I had my share of injuries.”

Atkins was offered the chance to play for the Air Force Academy, but he turned it down to pursue a career in medicine.

“From football and from some of the ways I injured myself, I had an opportunity to have some orthopedic surgery, got introduced to it and decided that that was what I wanted to do,” he said.

Atkins has two adult sons who played high school ball, and he says he is happy they did. He has two younger ones who are now playing in a flag league. Whether they will progress to tackle ball hasn’t been decided.

He cautions that football isn’t for everybody.

“It was really an individualized decision for me,” he said. “For some people it probably is not a good idea for them to play, but I’m happy I played.”

Joey Chandler and Molly Catherine Walsh contributed to this report.

Tommy Deas, Joey Chandler and Molly Catherine Walsh of The Tuscaloosa News discuss the “Should Your Kid Play Football?” project on this podcast, which takes the listener into the origins and process of putting the special report together. The project’s major contributors also talk about what they learned in reporting on the issue.

Executive producer Molly Catherine Walsh examines the question “Should Your Kid Play Football?“ in a video documentary that includes interviews with Alabama coach Nick Saban, former Alabama and NFL quarterback Richard Todd and many others. It explores the medical issues and benefits of playing the sport, as well as why the game is so important to so many.

1 in 4 say no to football

Drew Hill | Special to The Tuscaloosa News

More than one in four people responding to a survey by The Tuscaloosa News said they would not allow their children to play high school football.

The Tuscaloosa News received 268 responses to its non-scientific sampling in July and August. The survey was promoted on social media on Twitter and Facebook, and in The News’ print edition.

Twenty-six percent of survey respondents answered no to the question “Would you allow your child to play high school football?” The other 74 percent said that they would let their child play.

Those who had played the game before were more likely to answer yes, with 82 percent of respondents who had played football saying they would allow their child to play.

Almost two-thirds — 65.7 percent — of those who responded reported they had participated in football. The most common level of previous play reported was high school, with 118 saying they had reached that level, while 29 said they made it to the college level and one said he played professionally. The remaining respondents said they stopped playing after the youth level.

On the other hand, most of the 18 percent of survey participants who played but would not let their child play pointed to the risk of serious harm, such as knee injuries and concussions.

Ninety-one percent of the respondents who played said they were glad they did, citing lessons of teamwork, camaraderie and toughness they learned through the game. The remaining 9 percent who said they were not glad they played referred to long-term injuries or a lack of ability on the field.

The vast majority of survey participants, 74 percent, reported they are from Alabama, with the others coming from other states such as Mississippi, Ohio, Oregon and Pennsylvania.

The respondents reported ranging in age from 18 to 92, with 222 (83.5 percent) saying they have children. Eighty-two percent of the respondents with children said they have two or more children.

Males, at 77 percent, responded at a higher rate than females.

Why play football?

Here are some responses sampled from The Tuscaloosa News’ survey cited by people who said they would let their children play football:

- Risk of serious injury is low.

- It is helping him maintain his interest in school, and drives him to maintain his grades to remain eligible to play.

- Football teaches life skills, lessons, discipline, etc.

- Football teaches a boy how to be a man, how to fight through adversity, how to be a leader.

- Beats soccer.

- It’s a good sport and team competition is good.

- Better equipment and knowledge today.

- No more dangerous than driving down the highway. People use injuries as an excuse for laziness.

- Team sports, especially football, allows young men to develop not only as athletes but as leaders off the field.

- Rite of passage, hazards can be minimized.

- Thousands of people play every year and go on and live long successful lives.

- Great experience physically and emotionally.

- Participation in sports in most schools in Alabama limits participant's time and energy (plus coaches don't allow or restrict) to hunt other risk-taking behaviors at this level.

- Discipline, pushing through challenges, comradery, physical fitness, teamwork.

- It allows people to gain friendships that they can carry on for years to come and can allow them to see how teamwork can come together so people will be able to reach a goal.

Why not play football?

Here are some responses sampled from The Tuscaloosa News’ survey cited by people who said they would not let their children play football:

- Costs outweigh benefits.

- CTE

- (High school) youths are still in a developmental period of life.

- I think it's too dangerous for them to play at the HS age.

- The more we hear about it, the more dangers they unveil.

- Because I still suffer from injuries that I received playing football, I wouldn't let my son play.

- Too dangerous, and there are other ways to learn the same lessons.

- Too violent. Lack of quality coaches.

- Almost every other sport or extracurricular activity available to a high school student would have a similar positive effect on my child and their academic career, without the pointless endangerment of their brain.

- Brain disease is real. Major obstacle for football to overcome.

- No need for lifelong aches and injuries with other options available. Head injuries are just one problem. Knee and back pain are also huge concerns with age. As an anatomy teacher in high school, we spend a decent amount of time on concussions and football.

- I don't feel the risk of head trauma negates the slight chance my child will get a scholarship. Not to mention the obscene amount of money schools pour into sports programs could be used to fund the arts and other programs that further their education.

- My children are not knowledgeable enough to understand the risk of playing high contact sports.

How to tell your kid he (or she) can't play

Tommy Deas | Executive Sports Editor

If your child wants to play football and you, as a parent, have decided not to allow it, you’re going to have to break the news.

Jon Solomon, editorial director of the Aspen Institute Sports and Society Program, has some ideas about how to have the conversation:

- Tell the kid there’s no reason to play tackle at all at a young age.

- Tell him (or her) that National Football League stars like Tom Brady and Drew Brees didn’t play tackle ball until much later.

- Get them excited about trying other sports, and explain how those skills could later help in football.

Solomon said the situation is different once kids are old enough to try out for a high school team.

"Once kids get into high school, I think they're more mature to make their own decisions about football," he said.

Parents should, in such cases, provide information about the risks and benefits of playing, Solomon says. He suggests parents should investigate the program that their child might be joining — including quality of coaching, safety practices and whether the program has a certified athletic trainer and/or other medical personnel available so that a kid old enough to play high school ball can make an informed decision.

Alternatives to tackle football

Tommy Deas | Executive Sports Editor

Here are some activities that parents can consider if they don’t want their children to play tackle football:

Flag football: Tuscaloosa County Park and Recreation Authority offers flag football for ages 5-12. Leagues start play each year in late August. Call 205-562-3200.

Soccer: Tuscaloosa United offers teams for boys and girls ages 5-14, with elite team opportunities for older players, also through PARA. (It should be noted that medical studies have also linked soccer to brain trauma.) Call 205-562-3200.

Other sports: Various team athletic activities — from baseball to basketball to tennis and track — are offered at area schools from the junior high level on up, as well as through youth programs. Check at your school, with PARA or the YMCA or local leagues.

Football manager or support personnel: Central High School offensive coordinator Corey Waldon urges those who don’t play to find a way to contribute. “Make sure they are around the program,” he said. “Water, stats, filming, whatever it is, it teaches them so much about life.” Parents or students can talk to coaches about opportunities.

Band: Playing with a school band offers some similar experiences to football, including hours of practice requiring dedication and discipline. Check with your local school.

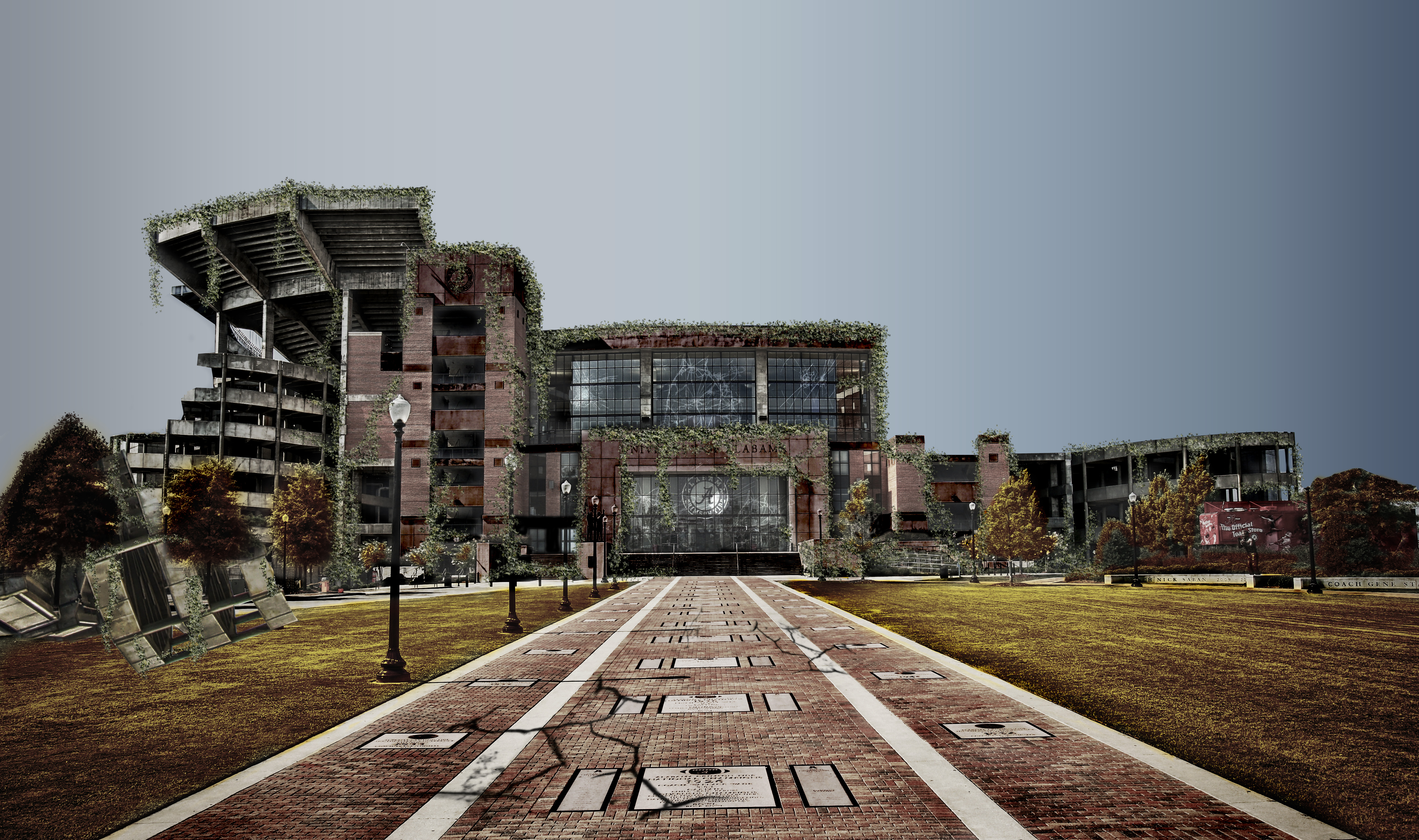

Alabama fans line the way for the Walk of Champions as the Crimson Tide makes its way into Bryant-Denny Stadium for the University of Alabama's homecoming game against Arkansas. Staff Photo | Erin Nelson

Football is part of the culture

Tommy Deas | Executive Sports Editor

No sport is more American, or more deep-rooted in the culture of this state and region, than football.

You can’t escape the passion for it if you live in Alabama.

A capacity crowd of 101,821 makes the University of Alabama’s Bryant-Denny Stadium the state’s fifth-largest city for a few hours on any given Saturday in the fall.

They come to cheer, to socialize, to eat and drink, and to be part of something greater than themselves. They wear crimson and white or houndstooth, they wave their shakers and shout “Roll Tide!”

“It’s community,” said Michael Wood, an American Studies instructor at UA. “It kind of ties into a need to identify with something, or a collective identity. It’s this kind of, I guess, human impulse to want to be part of a community, to participate in a community, and communities have rituals.”

Very few things bring more people together.

“I wouldn’t say it’s the same importance as religion, but it’s close in the South,” Wood said.

How did it come to mean so much? To understand football’s importance, particularly in the South, you must first understand its history.

The South rises

The sport began to migrate to Southern colleges in the 1890s, but the brand was considered inferior. Still recovering from the Civil War, the region was seen as a backwater home to hicks and dirt farmers. There was little in which residents could take pride.

A few decades later, the South began to make some noise. Alabama defeated Penn, 9-7, in 1922 in Philadelphia, notching a historic victory over an Ivy League foe when teams from the East were considered superior.

The victory that put Alabama — and Southern football in general — on the map was the Jan. 1, 1926, Rose Bowl, where UA defeated Washington, 20-19.

“There had been intersectional games between Southern teams and Northern teams, and most all of those games had all sorts of Civil War allusions, kind of attempts for the South to redeem themselves and those sorts of things,” Wood said. “It was not uncommon for Southern teams going to the North to have Dixie being played and those sort of trappings of the Old South and Southern identity — especially white Southern identity — tied to it.

“So the Alabama Rose Bowl in 1926 was kind of the breakthrough. The year after that, Alabama’s invited again, tied a Stanford team that was coached by Pop Warner, so it was a major deal: It wasn’t a fluke that a Southern team could play at a high level.”

From that point on, football was king in Alabama.

A new pastime

Baseball had been considered America’s national sport, but football took over. It happened, in large part, because of television.

Professional football captured the nation’s imagination when Johnny Unitas led the Baltimore Colts to a sudden-death, overtime victory over the New York Giants in the 1958 National Football League championship game.

In the following years, the pro game garnered more attention with color TV coming along right around the time of the fledgling American Football League — its biggest star being former Alabama quarterback Joe Namath of the New York Jets — competing with the more established NFL.

The two league champions were pitted in a universal championship game in 1967 in what would retroactively come to be known as Super Bowl I. By the start of the 1970 season, the NFL and AFL merged into one league.

The college game also continued to gain an audience as football became the nation’s favorite sport.

“It’s pretty much permeated all classes in the U.S. It’s not just a sport of the upper class or the lower class. Pretty much all of U.S. society has embraced it one way or another,” Wood said. “You can see that through ticket sales, through television, through participation as well.”

Changing the game

Football played a major role in bringing acceptance for integration of colleges in the South. It happened slowly, but the game helped pave the way.

At Alabama, Paul W. “Bear” Bryant began recruiting African-American athletes in the early 1970s. White fans found themselves cheering for athletes of a different skin color.

“Once you break that barrier … racial identities kind of fall by the wayside in terms of competitive advantage,” Wood said. “You want the best players.

“It takes more time for the fans to accept it than it did coaches, because coaches see football players and wins and losses and that sort of thing.”

The game continues to impact race relations, on a more personal level.

“It’s still the only sport where every player needs every teammate on every play just to survive,” said Bill Curry, a former University of Alabama head coach who played in the NFL for 10 years. “You can’t be a racist and step in the huddle, not anymore. You can’t hate somebody because of where they came from or their religion. You step in the huddle, you’re going to play with whoever’s there, and you’re going to learn to get along. It’s just a great lesson.”

A common cause

Football’s importance shows at the grassroots level in high schools across the land. Those who have played the game have experienced its social ties.

Savannah Reier played soccer and basketball at Northridge High School, and kicked on the Jaguars’ football team. As a women’s basketball player at Shelton State Community College, she has played in a junior college final four.

For her, there’s nothing like football.

“I miss the Friday night lights,” she said. “There’s nothing like getting that tight win on a Friday night and not leaving the field until 10 o’clock at night and everybody’s celebrating and your whole school is about that team.

“That’s something that I miss the most about it. That bond that I had with everybody on my team and at my school and the whole community, it’s something that was really special to me.”

Candy Chapman and Tonya Wilson encourage game attendees to make a donation as part of the "Split the Pot" drawing at halftime at Gordo High School on Friday, Sept. 29, 2017. Staff Photo | Erin Nelson

Where football means everything

Joey Chandler | Sports Writer

GORDO – Welcome to Gordo, Alabama.

Population as of the 2010 census: 1,750.

A community where football means everything.

It’s a Friday evening in late September, two hours before kickoff at Libby Hankins Field. Dierks Bentley’s “Free and Easy (Down the Road I Go)” is blaring from the loudspeakers. A group of Greenwave ball boys in jerseys and yellow shorts are on the field playing a pick-up game.

They are the future generation of Gordo football, products of a culture into which the importance of the sport has been ingrained from the very beginning.

Greenwave senior Collin Herring can’t remember a time where he didn’t attend games on Friday night. He looked up to the high school players when he was younger, and now he’s one of the ones who is idolized.

“It kind of speaks for itself,” Herring said. “If you are not from Gordo and a team comes here, you just look around and see how many people are at the game watching. The whole community goes. It’s like a ghost town when there is a football game. You could get away with any crime when a game is going on, because everybody is here.”

Earlier in the day, the entire school district – kindergartners to seniors – left class to attend the weekly pep rally.

“The easy part for me here is the community raises their children to respect Gordo football, and to hopefully be Gordo football players,” Greenwave head coach Ryan Lolley said. “These guys probably receive a lot more pressure from their family than they do me to be the very best that they can be, and that is where the tradition comes in for this place. All I am is fortunate enough to be the luckiest man in high school football to get to coach here. Because our players make it easy. They get it done for us.”

In contrast to declining participation numbers in some areas, Wayne Davis, president of the Gordo Youth Athletic Association, said enrollment is the highest he’s seen in the past decade.

There are 76 children in Gordo participating in youth football, ranging in ages from 7 to 12. There were 56 in 2016 and 47 in 2015. They compete in the West Alabama Youth Football Association.

Davis is a product of Gordo football. A member of the 1980 state championship team, he went on to become the all-time tackling leader at the University of Alabama and play in the National Football League. He returned to his hometown as a pastor, and his oldest son, Ben, plays linebacker at Alabama.

“It didn’t start yesterday and it didn’t start last year, but I think it has been over the course of decades, I believe, going all the way back to the 60s, that Gordo has always been a town that has supported and lifted up football especially,” Davis said. “I think that tradition, just like at Bama, has sparked an interest in the people and in the community, and I think they have seen others benefit from Gordo being a town that accepts the sport of football.

“Individuals have benefited from it. I know I have. Being a product of football in Gordo from third grade and going all the way through junior high, high school, going into college and even to the highest level of football in the NFL, so that is what it provided to me as an athlete, and now as a citizen in the community. Giving back to the community has been a joy for me.”

With a strong history of gracing the weekly Alabama Sports Writers Association prep football rankings, the Greenwave has won four state championships and 15 region titles, and is knocking on the door of No. 16. In their careers thus far, Gordo’s seniors had lost one regular-season game by mid-October this year and have made two trips to the state semifinals.

“Gordo is very much tradition. They are families of hard-working people and they expect that out of the kids,” former Gordo and Fayette County coach Waldon Tucker said. “Other than God and family, the biggest thing that happens here in Fayette, Alabama, is on Friday nights, and it’s the same way in Gordo. I can’t speak (for other communities), but I can speak for those two, because I’ve been there. It is just expected of those kids to play.”

Brookwood High School football players give red and white flowers to Beth Terrell before the the Hillcrest vs Brookwood football game at Brookwood High School Photo | Jake Arthur

'All about school spirit'

Drew Taylor | Staff Writer

Making noise with anything they could get hold of, students at Brookwood High School began shouting as John Martin Wagner took the microphone.

“We need the student section to come out tonight and be loud,” the tight end and team captain said during a pep rally at the school in early October.

However, the pep rally was about much more than that night’s football game against McAdory. Decked out in pink shirts and bandanas, the student section cheered just as loudly for the speaker before Wagner: Beth Terrell, a student who had been diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia. Through a “Pink Out” at the pep rally and again that night at the game, students and teachers wore pink to honor those who had fought cancer.

Wearing a surgical mask, Terrell spoke to the crowd of students she had not been able to see for months because of her illness.

“I am so happy to be with you all again at Brookwood,” Terrell said. “I’m just sad I won’t be able to stay.”

Marcy Burnham, health science teacher at Brookwood, said she was touched by the reception Terrell received from the students and how their commitment to her and others was on display that night.

“I don’t think I’ve ever heard them that loud before,” Burnham said.

Brookwood High principal Mark Franks said pep rallies often are about much more than football.

“Pep rallies are one of those things where there are a lot of traditions,” Franks said. “At Brookwood, our kids are very excited about them and it builds good morale.”

In many high schools across Alabama, football is the most popular and well-attended sport. Because of that, many administrators and people in the community believe it plays an important role in both education and community-building.

Franks said he believes football and other sports are crucial to athletes’ education and their own accountability.

“We tell them that if you’re an athlete, you have two jobs,” said Franks, who coached football at different schools in Alabama before coming to Brookwood. “You represent yourself in two different ways now.”

Alivia Scruggs, a senior at Brookwood, was one of the many students banging pots and pans together, yelling in support of the football team during the pep rally. Scruggs said football and other sports inspire her to focus on her studies.

“It makes you proud to be part of this school,” Scruggs said.

Franks said high school football also plays a crucial role in the community, which he said fills the stands in droves every Friday night.

“No doubt, the school is usually the lifeblood of the community,” Franks said. “If there weren’t schools, there wouldn’t be communities.”

Dennis Alvarez, principal at Sipsey Valley High School, said he often sees the team’s football schedule posted in the Sipsey Valley community, and that many people from the area attend games.

“I think our community supports the school and will come out for it,” Alvarez said.

Christy Haynes, a mother with children at Hillcrest High School, said the community supports the team. Haynes, an alumna of Hillcrest, has a daughter, Emma, who is a cheerleader. On Friday nights, Haynes will be at the football stadium to support her daughter and the team.

“It has to do with school pride,” Haynes said as Hillcrest played against Paul W. Bryant High in early October. “It makes a big difference when they feel like they are involved.”

On the other side of the field, Dewayne Melton sat in the stands, watching his son, Trent Poole, who plays for Bryant High. Melton said that even if his son did not play football, he would still go to the games.

“It’s something to do in the city,” Melton said.

Melton said that at the end of the day, high school football is about pride.

“It’s all about the school spirit,” he said.

Reach Drew Taylor at drew.taylor@tuscaloosanews.com or 205-722-0204.

'Concussion awareness has shot through the roof'

Tommy Deas | Executive Sports Editor

It isn’t likely a doctor will tell you football is good for you.

That’s because it’s not.

Whatever the benefits of playing, health is not one of them.

Football has the highest injury rate of any high school sport, even when factoring in higher participation numbers. Basketball and soccer are contact sports; football is a collision sport.

Football is responsible for more concussions than any other sport at the high school level, and medical research continues to show that repeated brain trauma often leads to serious issues later in life.

“What has happened because of all (the recent publicity about this issue) is concussion awareness has shot through the roof,” said Dr. Jimmy Robinson, medical director and head team physician for the University of Alabama since 1989 and also medical director for the Alabama High School Athletic Association.

A study of brains of former players — many of whom had reached the National Football League level — after their deaths has revealed a disturbingly high incidence of chronic traumatic encephalopathy, a progressive and degenerative brain disease better known as CTE.

Parents deciding whether to let their children play football need to be aware of the possible dangers of both short- and long-term effects of playing the game.

Game-changing study

CTE was first diagnosed in a former NFL player in 2002, but it took years of brain donations by deceased former players to allow a comprehensive study. That study, headed by Dr. Jesse Mez, assistant professor of neurology at Boston University’s Alzheimer’s Disease Center, and published in July in the Journal of the American Medical Association, determined that 87 percent of 202 studied brains showed signs of CTE. Of 111 brains of former NFL players examined, 110 — 99 percent — had CTE.

The disorder manifests as changes in behavior and mood, with impulse control issues, aggression, depression and paranoia commonly arising in earlier stages. In later stages, symptoms include memory loss, confusion and impaired judgment, with the onset of dementia following.

Medically, it is characterized by the collection of deposits of biomolecules known as tau proteins in the brain.

“The location of the tau protein is in a different part of the brain than we would normally see with, let’s say, Alzheimer’s, but the clinical picture is almost identical, and it’s very difficult to distinguish the two,” Robinson said.

There is no way yet to detect CTE in a living patient.

“The only test is autopsy,” Robinson said.

The study noted that the sample was skewed, since the subjects who donated their brains were suffering from symptoms associated with the disease. Even so, the findings have resonated, creating a perception that playing football leads to long-term brain damage.

Robinson says that isn’t necessarily so.

“There’s hundreds and millions of athletes who played the sport who did not demonstrate those signs or symptoms, whose brains were not sent there,” Robinson said.

Concussions may not be the only problem. Researchers are trying to link CTE to sub-concussive blows like repeated helmet-to-helmet contact between linemen on every play.

“We don’t know that,” Robinson said. “People are trying to study what the impact forces are in an offensive lineman by putting these helmet sensors in and trying to see do they sustain more hits, greater power with those hits, than some of the other athletes on a regular basis, and that is still being looked at right now.”

High injury rates

Injury report

Of more than 13 million estimated total injuries in high school athletics over the last 10 years, more than 5.5 million — 42.2 percent — have come from football.

Football would be dangerous even without its association with CTE.

According to the National High School Sports-Related Injury Surveillance Study, which monitors injury information for the National Federation of State High School Associations, more than 5.5 million football injuries have been sustained at the high school level over the last 10 years, accounting for 42.2 percent of all injuries in high school sports.

Of more than 2.5 million estimated concussions sustained in high school athletics over the last decade, almost 1.2 million — 46.2 percent — have come from football.

Concussions have been the most prevalent type of injury to be sustained by high school athletes in each of the last seven years, ahead of ankle sprains and strains. In football, concussions have been the most frequent injury for nine straight years.

Concussions

Of more than 2.5 million estimated concussions sustained in high school athletics over the last 10 years, nearly 1.2 million — 46.2 percent — have come from football.

Concussions have accounted for 25 percent or more of all football injuries for the last three years, and 23.6 percent or more in each of the last seven years.

The incidence of concussions in high school football has jumped 87 percent in the last 10 years, according to the national study.

That, Robinson said, is actually progress. He said he doesn’t believe that the numbers have changed so much as awareness has increased.

“I tell people sometimes that the number of concussions that I see and that we’re experiencing in the state of Alabama is growing, and that makes me happy,” he said. “Because people are recognizing the signs and symptoms of concussions, coaches are getting trained on concussion recognition awareness, parents are becoming more and more aware and the athletes become more aware.”

Football also results in other types of serious injuries. Of all injuries in the sport at the high school level, between 7 and 10 percent have required surgery in each of the last nine years.

Dr. Tosh Atkins, an orthopedic surgeon with University Orthopaedic Clinic, estimates that he’s performed about 20,000 surgeries over the last 22 years. Even though the clinic treats football players of all ages, he says few of those surgeries have been related to the sport. More often, he treats bone and joint disorders and arthritis.

“Probably 2 to 3 percent football-related,” he said. “Fractures — finger fractures, forearm fractures — ACL (anterior cruciate ligament) tears and meniscal tears with knees, and then we see a lot of bruises and strains or minor injuries, ankle sprains and those kinds of things.”

The trend in football injuries at the high school level is encouraging. With football injuries topping 600,000 in the 2013-14 school year, the number has fallen steadily in the last three years and was down to less than 445,000 last season, the lowest in the last 10 years. The drop in injuries was nearly 29 percent, while the drop in participation was around 3.3 percent.

The frequency of injury in football has also fallen steadily over the last decade, with the national high school study concluding that injury-per-exposure rates — with each game and practice counting as one exposure — dropping from 4.18 per 1,000 athlete exposures to 3.56. But that is still a higher rate than with any other sport.

Death by football

Football from the youth through professional levels has been responsible for 1,848 deaths since 1931 (with no data for 1942) — an average of 21.5 per year — according to the Annual Survey of Football Injury Research carried out by the University of North Carolina’s National Center for Catastrophic Sports Injury Research.

Of that total, 1,048 deaths were a direct result of the sport (defined as catastrophic injury in a game or practice), and 800 were indirectly attributed to football (defined as being a result of “exertion or by a complication which was secondary to a non-fatal injury”).

In the last 10 years (through the 2016 season), football has caused 161 deaths, 51 of them directly, a drop to roughly 16 deaths per year in that span.

From 1900 to 1905, 45 players died playing college football, causing a national backlash that nearly ended the sport. Participation was much lower during that time, with many schools not fielding teams. Professional and high school football didn’t become widespread until years later.

Addressing safety

Coaches at the college, high school and youth levels undergo concussion awareness training, and protocols are in place to monitor and evaluate players who are concussed. They are removed from competition and are not allowed to return until cleared by medical personnel.

“So the fact that people are recognizing it, they’re getting treated earlier, they’re being held out longer and not returned until it’s a lot safer, I think the sport is becoming safer because of that,” Robinson said.

Robinson has walked sidelines at high school and college games for 30 years. He sometimes even takes helmets and shoulder pads from concussed players who are determined to return to action.

“It’s the ones who go back in too early that have problems,” he said.

Game rules have evolved in an effort to eliminate injuries.

“Every change,” said Steve Savarese, executive director of the Alabama High School Athletic Association, “has been to make the game safer.”

Safer, perhaps, but there are gaps: The AHSAA recommends but does not require an ambulance nor a physician or certified athletic trainer to be present at every contest. Most games are covered, but some schools in more rural areas have difficulties. AHSAA member schools are required to file an emergency action plan for all sports and venues that includes procedures on how to contact first responders if an ambulance is not available.

CTE: Frequently asked questions

Tommy Deas | Executive Sports Editor

Most people became familiar with the term CTE after the release of the 2015 film “Concussion,” which chronicled Dr. Bennet I. Omalu’s fight to get the condition recognized by the medical community and the National Football League. Here are the answers to some frequently asked questions, gathered from published material from the Brain Injury Research Institute, the Concussion Legacy Foundation and the Mayo Clinic.

What is CTE?

Chronic traumatic encephalopathy is a medical condition of brain deterioration that has been linked to football and other sports with a high frequency of concussions and repetitive brain trauma. It is a progressive, degenerative disease, meaning it gets worse over time and causes loss of brain mass, especially in certain areas (although it can also cause swelling in some areas of the brain).

How is it caused?

According to published medical studies, the disease is believed to be caused by repeated head trauma endured by football players, boxers and military personnel. Some researchers believe that the cause is not necessarily repeated concussions so much as continuous sub-concussive blows, which do not result in full-blown concussions but impact the brain over time. There is no consensus on exactly what it takes to cause CTE, and genetic and other factors may play a part.

What are the symptoms?

CTE has been discovered in people as young as 17, but it usually doesn’t manifest until a patient reaches the late 20s or 30s, years after the onset of head trauma. It exhibits in behavior and mood, with impulse control issues, aggression, depression and paranoia commonly arising in earlier stages. In later stages, symptoms include memory loss, confusion and impaired judgment, with the onset of dementia following.

How common is it?

It is not known how common the disease is, but it appears to be most prevalent in those who have been subjected to long-term, repeated head trauma. There are no known cases of CTE being caused by a single concussion with no other brain trauma.

Can it be treated?

There is no treatment for CTE. Doctors advise avoiding head trauma as a preventive measure.

How do I know if I have CTE?

No test has been developed yet, although experts are working on creating scans to detect it. Researchers have only been able to diagnose it postmortem in those whose brains have been donated for study, but diagnostic criteria have been established to allow neuropathologists to accurately diagnose it.

How to tell if you have a concussion

A concussion is a traumatic brain injury that can be caused by a blow to the head or violently shaking the head and upper body. It affects brain function, usually temporarily. It can cause loss of consciousness, but not commonly.

It is possible to have a concussion and not realize it. Symptoms do not always show up immediately and can last for days, weeks or longer.

Here is a list of concussion symptoms as described by the Mayo Clinic:

- Headache or a feeling of pressure in the head

- Temporary loss of consciousness

- Confusion or feeling as if in a fog

- Amnesia surrounding the traumatic event

- Dizziness or “seeing stars”

- Ringing in the ears

- Nausea or vomiting

- Slurred speech

- Delayed response to questions

- Appearing dazed

- Fatigue

Delayed symptoms may include the following:

- Concentration and memory issues

- Irritability

- Sensitivity to light and noise

- Sleep problems

Symptoms in children, as described by the Mayo Clinic, include:

- Appearing dazed

- Listlessness and tiring easily

- Irritability and crankiness

- Loss of balance and unsteady walking

- Crying excessively

- Change in eating or sleeping patterns

- Lack of interest in favorite toys

The Mayo Clinic advises seeing a doctor within one to two days if you or your child experiences a head injury, whether or not emergency care is required.

If the following symptoms after a head injury are apparent, emergency care is recommended:

- Repeated vomiting

- Loss of consciousness for longer than 30 seconds

- A headache that gets worse over time

- Changes in physical coordination, like stumbling or clumsiness

- Confusion or disorientation, including difficulty in recognizing people or places

- Slurred speech or other changes in speech

The Mayo Clinic advises athletes should not return to play or vigorous activity when concussion symptoms are present. An athlete should be medically evaluated by a professional trained in evaluating and managing concussions before being cleared to return. No athlete should return to play on the same day as sustaining a concussion.

— Tommy Deas

Coach Sam Collins watches as the kids on his flag team run a play during practice at Sokol Park North. Staff Photo | Gary Cosby Jr.

Flag football on the rise

Tommy Deas | Executive Sports Editor

Football participation across the nation at the high school level is down 3.5 percent over the last five years and 4.6 percent over the last decade, a trend that shows no signs of abating.

The data is mixed locally. Total participation at 14 high schools in Tuscaloosa County is up 12 percent from two seasons ago, according to research by The Tuscaloosa News, but youth football numbers present a different picture, with flag football becoming increasingly popular and participation in tackle football dropping.

The number of players in the Tuscaloosa County Park and Recreation Authority flag football program surpassed the number playing tackle ball in 2015, and in the last three years, tackle participation has held steady at well below 400 players.

The youth football numbers suggest that parents are increasingly reluctant to enroll their children in tackle football in the wake of mounting medical evidence linking the sport to brain trauma.

Those numbers are dramatic:

- Flag football participation is up more than 100 percent over the last five years in the PARA program, from 237 to 475, while tackle football participation has dropped 19.5 percent.

- Flag football participation in the PARA program reached a high of 531 last season, although it has dropped to 475 this fall.

- Current flag participation is still higher than tackle participation at any point in the last five years, with 120 more kids playing the flag version than tackle in PARA leagues this season.

“It’s a great alternative,” said Wyn Fortenberry, a real estate salesman who has two sons playing flag ball. “It’s like an organized backyard game. The kids love it. I think it’s brilliant.”

Raeana Thomas put her son in flag football for safety reasons.

“I thought it was gentler,” she said. “My husband wanted tackle. Safety is a concern, but I wouldn’t keep him from having the (football) experience. He climbs trees. He wears a helmet when he rides his bike.”

Christie Wendt has a son and a daughter playing in the flag league. Her 8-year-old boy will probably move on to full-contact tackle ball.

“I just wanted him to know what was going on before doing the more physical aspect of it,” she said. “He’s one of the bigger kids. He wanted to play tackle, but mama wasn’t ready for that.”

Flag proponents believe that form of football allows for more teaching at an early age. Matt Jones, a local attorney who walked on at the University of Alabama after playing at Tuscaloosa County High School, coaches a youth flag team in the 5-6 age group. He said he wanted his son to play flag ball first.

“There’s a lot of technique and fundamentals that go into tackling and playing football whether you’re 40 or you’re 4,” he said.

The local youth football picture isn’t completely clear, as PARA ball is not the only program available. The West Alabama Youth Football Association declined to provide hard numbers, but league officials say participation remains robust. What began some 20 years ago as a federation of 18 total teams (six franchises with three age groups for each team) has grown to 47 total teams (13 franchises, each with three or four age groups) from a geographic area that includes Tuscaloosa, Pickens, Hale, Bibb and Marengo counties. According to information provided by Burkles Davis, WAYFA president, the original teams averaged about 26 or 27 players each. With an estimated 800 total players now, the average is about 17 players per team.

“They’re probably up,” Davis said of the league’s total participation numbers, noting that franchises have been added as the league has expanded geographically.

He said the league considered adding flag football in the 5-6 age group (the youngest the league offers) but found little interest.

“It was probably 95 percent no,” he said. “If they wanted them to play, they wanted them to play real football from the beginning. Some people don’t want to play tackle that early, but the ones we have want them to put on a helmet and shoulder pads and play tackle.”

Officials from both leagues say numbers have dropped in recent years in the upper age groups, with more parents opting to have their kids play for their junior high school teams.

The combined numbers from the PARA and WAYFA leagues paint a picture of strong participation, regardless.

“It’s a high number of kids,” said Wendy Harris, director of leisure services for PARA. “If you look at the number of tackle teams in Tuscaloosa for a county this size, I would say the number has grown if you count our teams plus the independent (WAYFA) teams

A fan gets gets concessions during the Arkansas-Alabama game on Saturday, Oct. 14, 2017, at Bryant-Denny Stadium in Tuscaloosa, Ala. Photo | Laura Chramer

Football is high finance

Tommy Deas | Executive Sports Editor

Football is money.

A single University of Alabama football game has a $19 million impact on the Tuscaloosa economy, and UA generally plays seven games per year at Bryant-Denny Stadium.

That’s $133 million per year, and it only scratches the surface of the sport's full economic impact.

But is it too big to fail?

Revenue generated by football fuels the local economy as well as the entire athletic department. At Alabama, football and men’s basketball are the only athletic teams among 19 sports the school fields that generate a profit, according to the school’s annual filings with the NCAA.

“If it fails, it could really force a depression both emotionally and financially,” said Wright Waters, a Tuscaloosa resident who is executive director of the Football Bowl Association and past commissioner of the Sun Belt Conference.

In addition to the $19 million in economic impact locally, each game generates an impact of $6 million per game elsewhere in the state. That comes from money spent by travelers on their way to and from games.

“We’re talking about something that is quantifiable,” said Ahmad Ijaz, executive director of UA’s Center for Business and Economic Research, which does an annual study of the university’s economic impact, which includes football.

Ijaz’s numbers are based upon more than 100,000 people in attendance for games and how much they spend, on average. UA is able to track ZIP codes of ticket holders and thus gauge how many come from out of town. The total impact is then determined from a multiplier used by the U.S. Department of Commerce that calculates how many times each dollar circulates through the local economy.

“For instance, if you spend a dollar, you buy something from me, then I’ll cover my cost — say 25 cents — and then I’ll go and spend 75 cents and so on,” Ijaz said. “That’s indirect spending.”

Football money permeates the local economy.

“It’s lodging tax, sales tax when people go out and eat, they buy gas here, so that’s all included,” Ijaz said.

Michael Hebron bought Rama Jama’s, a burger-fries-and-breakfast restaurant across the street from Bryant-Denny Stadium, in August. He knows what Alabama football means to his business; on a normal weekday, the restaurant serves about 250 people, whereas on a game day, it serves between 1,800 and 2,000.

“Those seven (home) games are probably responsible for over a third of the overall annual revenue,” he said. “Alabama football is hugely important to us.”

The economic impact goes beyond what can be easily measured.

“People work concessions; those add more jobs for people who supply food, drinks and everything,” he said. “Some of that, it’s difficult to quantify, like how many people are charging $10 to $15 to park in their yards, but they’re there. And then they go out and spend that money, so that’s further economic impact.”

Beyond game days, Alabama football is a huge moneymaker. According to numbers supplied by UA to the NCAA, football-related revenue at the school — which includes money from ticket sales, television rights and other sources — has gone up every year since 2005 and more than doubled in that span. In 2005, Alabama reported nearly $43 million in football revenue; last year, it was close to $104 million.

The Southeastern Conference distributed $122 million to member schools in 2007. That number rose nearly 364 percent over a decade to $565.9 million last year. Most of that revenue comes from television contracts that are heavily valued by football game rights. The disbursement rose 93.2 percent after 2014 with the creation of the SEC Network. Alabama reported receiving more than $20.8 million in football television revenue for last season on its annual filing with the NCAA.

The economic impact of football isn’t just local.

Postseason collegiate football games generate $1.5 billion in impact in December, according to a study by San Diego State University and George Washington University.

“That is larger than the gross national product of some Third World countries,” Waters said.

All that revenue helps make other collegiate sports programs possible.

“There’s a lot of volleyballs, golf balls, tennis balls that are bought with proceeds that come from football one way or the other,” Waters said. “On most campuses it’s the only (sport) that’s returning any revenue, that at the end of the year there are returning net dollars.”

“It’s an expensive sport, but it does have a financial upside.”

Football coaching salaries have risen dramatically over the last decade. When Nick Saban arrived at Alabama as head coach in 2007, his $4 million-a-year salary was groundbreaking; only two other SEC coaches were making more than $2 million at the time. Now, Saban makes almost $7 million a year and no head coach in the conference makes less than $2.35 million.

Assistant coaching salaries have also skyrocketed, with about a half-dozen SEC coordinators making $1 million or more, including Jeremy Pruitt and Brian Daboll, Alabama’s chief defensive and offensive assistants, respectively. Texas A&M’s John Chavis is the highest-paid collegiate assistant coach in the country at more than $1.5 million per year.

Athletic departments at the vast majority of colleges are not self-sustaining financially. Most rely on income from student fees or other institutional funding. Football, however, provides the most revenue of any sport and helps offset those losses.

And ticket money isn’t the only consideration.

“A lot of people want to look at the gate as the only football revenue, but you’ve got to look at would people be donating at the same level if you didn’t have football?” Waters said. “Would you be selling the same amount of merchandise at a program without football? Those are important questions.”

At UA, the impact is even deeper. Football has been a major factor in the exponential growth in the university’s enrollment, which has coincided with the Crimson Tide’s resurgence as a national power under Saban.

Four years before Saban’s arrival as head football coach in 2007, UA had begun a concerted effort to attract more students. From 2003 to 2006, enrollment grew by 21.6 percent, from 19,633 students to 23,878. During Saban’s tenure, however, enrollment has grown by 61.5 percent and stands at 38,563 as of the current semester.

“Expansion of the university that’s been going on for the last 10 years, football has a tie to that,” said Michael Wood, an American Studies instructor at UA. “It couldn’t have happened without Saban being here. That’s driven interest in enrollment.”

With that growth has come new dormitories and academic buildings, along with several hundred new faculty hired.

Failure of football is not an option, economically, especially in Tuscaloosa. The sport’s impact is essential to the livelihood of so many.

Alabama’s ability to drive enrollment upward so dramatically based on football success isn’t a model other schools can count on mimicking, according to Richard Vedder, professor emeritus of economics at Ohio University and director of the Center for College Affordability and Productivity.

"You are lucky in Tuscaloosa that the athletic component has been so successful,” he said. “Alabama is one of the few schools in the country that I think can claim athletics have paid off for them."

Prep football also generates significant revenue. According to research by The Tuscaloosa News, attendance at 12 high schools in Tuscaloosa County over the 2014-16 seasons was more than 185,000, with an average of more than $418,000 per year in ticket revenue. Two schools declined to provide gate receipt data.

Those funds help sustain athletic programs. Anthony Harris, athletics director for Tuscaloosa City Schools, said gate revenue was important in keeping athletics programs alive during recent years of proration when state funds were cut. Gate money is used for travel and equipment, and sometimes to help out other sports.

“Football is the biggest income item,” he said. “We do have some schools that can generate enough revenue to help out other sports.”

Ed Enoch contributed to this report.

Tuscaloosa County head coach John Holladay leads his team in the first practice of the season. Staff Photo | Gary Cosby Jr.

The benefits of football

Joey Chandler | Sports Writer

Waldon Tucker, who retired in 2011 as the winningest coach in Alabama high school football history, is an advocate for the benefits of playing the sport, both on and off the field.

“I can't see any reason for anybody not to want to play football, and I am going to tell you what else it does: It builds communities,” said Tucker, the retired Fayette County High School coach for whom the school’s field is named. “It keeps communities together. Our churches here in Fayette get these kids together once a week and feed them. What is it about it that people wouldn’t just love? It builds character. It builds self-esteem. It is just a great team sport.”

Tucker’s views were echoed among coaches and administrators from across the state.

“There is a laundry list of positives. Everything from character development to relationship building to humanity to sacrifice,” said Steve Savarese, executive director of the Alabama High School Athletic Association. “I think one of the greatest life lessons is learning how to get along with others, learning how to address adversity, that character development after you lose, and following a disciplined structure. I think it’s the closest thing that our student athletes have to our military training.”

When asked about the positives of playing the sport, more often than not coaches discussed the impact of the game beyond an athlete’s playing days.

“When they get that job and the power bill is due and they’ve got to buy formula for the baby and things like that, they are going to find a way to do it because they found a way to get it done out here when times are tough,” Gordo coach Ryan Lolley said.

Tuscaloosa County coach John Holladay stressed the importance the game plays in molding a player's outlook on life.

“You are going to have to have mental toughness. You have to be tough overall, but we are more concerned about the mental toughness than we are the physical toughness,” he said. “Of course it is a physical game, and you need to be that, but if you are not mentally tough, it is going to be tough to fight in this world.

“At this age with human growth and development, some of them are coming out of that selfish stage, so if we can learn to put someone else in front of us, that someone else is more important than us, we are going to do that later in life. Whether it be our spouse or our children or whoever has got to be more important than ourselves, and I think those are unbelievable lessons that this sport teaches.”

Alvin Briggs, director of the Alabama High School Athletic Directors and Coaches Association, played for Auburn University and the Dallas Cowboys. He is an advocate for the role football plays in bringing together people who may have never interacted outside of the sport.

“I wouldn't just say football, but I would say sports in general, it teaches you to get along with a fashion of society that you have to step outside your comfort zone to be with: to become a team, to develop a chemistry,” Briggs said. “To learn about somebody else’s culture and their likes and dislikes. I have some of my greatest friends through sports and through the love of sports.

“Sports is what true life is about, I believe, because when you go into the workforce, you are going to meet different walks of life, and it is not going to be your same friend that you grew up with, or that team that you played with, so it teaches you to work with others.”

Alberta Bulldogs players Zacovion Nichols and Damarian Myles walk off the field at halftime during a 6-8 year old game of tackle football at Sokol Park Monday, October 9, 2017. Staff Photo | Gary Cosby Jr.

The perils and risks of football

Joey Chandler | Sports Writer

The long-running, nationally syndicated comic strip “Hi and Lois” addressed the safety concerns of playing football on a Sunday this past September.

“I love the sounds of a hard-fought high school football game,” teenager Chip Flagstone said, sitting in the stands.

“Me too,” his friend agreed, smiling.

The sequence progressed to show impact during the game, accompanied by sounds.

Thump! Wham! Thud! Crack!

The final noise the boys heard was from an injured player being held upright by two coaches on the sideline: “Ow!”

“I’m sure glad we’re not playing anymore,” Flagstone said.

His friend agreed once more.

The boys were no longer smiling.

Over the last 10 years, 42.2 percent of all injuries and 46.2 percent of concussions sustained in high school sports occurred during football games or practices, according to data collected for the National Federation of State High School Associations.

Harvey Logan, 31, known around Tuscaloosa as “Harvey the Car Houdini” at Auto Max USA, played linebacker at Central High School and Stillman College. He has slipped discs in his lower back and a degenerative spine condition. He relates those health problems to football.

He played from the ages of 12 to 21, leading to a daily struggle that isn’t visible when watching the fun, energetic persona he’s known for on his Facebook page and in his commercials.

“Every day, just about every step I take, I have got some pain. I deal with people on a regular basis selling cars and get people who were never really athletically inclined and never played sports and they are walking around fine, and here I am — from a visual appearance I look good because I still work out and stuff, but internally, there is a lot going on,” he said.

Logan has two young children, a boy and a girl, and said he does not want his 6-year-old son to play football because he believes the physical toll can negatively impact his quality of life.

At the moment, their focus is on baseball.

“From a long-term standpoint, football is probably something, outside of boxing or MMA (mixed martial arts), the most dangerous sport you can play,” he said. “You have guys playing baseball until they are 60-something years old. In football, you turn 30 years old and you are considered old.”

Jason Bothwell, an assistant at Northridge High School, played football at Wenonah High School in Birmingham from 1997-2000 and then at Alabama State University. He said he doesn’t see the game becoming safer.

“I think football has changed because there’s not a lot of teaching of the fundamentals,” he said. “We’ve evolved to a time in the game where it’s just, put the ball in your playmakers’ hands and whoever scores the most points wins. There’s not a lot of attention put on stopping anybody; it’s just let’s play, play, play.

“From an injury standpoint, I’m not sure if it’s the quality of the equipment or the quality of the participants, but I don’t recall that many injuries in my time of playing. Whether it’s the type of equipment that we played with or the type of food we ate, who’s to say?

“I don’t think it’s safer now because of the lack of attention to fundamentals. A lot of kids are just playing with reckless abandon, but it’s starting to do more harm to them than it is to other people. I think a lot of that is on the lack of formative knowledge on how to perform different skills and tasks and positions within the game.”

Longtime Hubbertville High School coach Lamar Harris agreed.

“They have come up with a lot of different rules that make it tough to teach a kid to play. When they are going to be out there, they need to know how to hit and they need to know how to tackle,” said Harris, who is in his 41st year coaching the Lions. “I am all for safety, don’t get me wrong, but football is a tough game. It is supposed to be a game of hitting, and kids have to be taught to do it, and you can’t just tell them, ‘This is the way you do it.’ They have to do it. It has to be done, and if you don’t, it is a disservice to the kids."

Savannah Reier kicked for the Northridge High School football team in 2015.Staff Photo | Laura Chramer

The kicker

Molly Catherine Walsh | Special to The Tuscaloosa News

It was picture day for the 2015 Northridge High School team, and the kicker was in the locker room with her mom, trying to figure out how to put on her football pants.

Savannah Reier had grown up the daughter of a football writer, Travis Reier, but her athletic capabilities had grown on the soccer, softball and lacrosse fields, as well as the basketball court, as she grew up. Her father had encouraged her since middle school to try football, but it wasn’t until the summer before 10th grade that Savannah tried it.

She loved it. It was unusual for a female to join the high school football team, but not impossible. She kicked for a year at her high school in Hilton Head, S.C., before the family moved to Tuscaloosa and she transferred to Northridge.

The Jaguars’ kicking coach was Jason Bothwell, who quickly realized she would add a diverse and winning quality to the team.

“Initially, honestly I thought it was just another female athlete wanting to break down barriers,” Bothwell said. “Once on the field and cleats laced up, I could see there was a different dynamic to her all around.”