Sounding the alarm on fentanyl

Fentanyl is on the rise in Lane County.

Just ask the 23 people who overdosed on the dangerous drug over four days in September. Or the 15 who overdosed in the first half of October. All survived, thanks to a medication that reverses the effects of opioids, but the flurry of overdoses has focused local attention on the drug.

Still, despite that spike, fentanyl’s prevalence in the community is difficult to gauge, according to Sgt. Dave Lewis, a Springfield police detective.

"I do know for a fact that the presence of fentanyl is on the rise here," Lewis said. "But I think it's more pronounced than we know ... Anytime there is a new trend in the drug world, law enforcement is generally behind, as far as figuring out the magnitude of it. But it's definitely here."

Fentanyl is just one piece — albeit a worrisome one — of a national opioid and drug overdose problem. More than 68,000 people died in the U.S. from all types of drug overdoses from March 2017 to March 2018, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control. More than half of those fatal overdoses were the result of prescription or illicit opioids. In Oregon, 547 people died of a drug overdose over that same period — up from 510 deaths the previous year. That's an increase of 7 percent, the CDC data showed.

Even more troubling: In Lane County, there were 40 opioid-related deaths in 2017, 60 percent higher than the state's rate, according to Lane County Health and Human Services.

Fentanyl is a synthetic opioid used to help relieve severe ongoing pain. It's appealing to users because it takes only a fraction of the amount — compared to other drugs — to get high. In Springfield, fentanyl has been found in powder, pill and patch form, and mixed into other drugs, most commonly heroin. Those who overdosed this fall ranged in age from their 20s to 50s, with the first three victims of the September overdose spree being 51-year-olds found in parked cars.

This year already, Springfield police have investigated at least six drug possession or distribution cases related to fentanyl, according to Lt. Scott McKee, including one since the string of overdoses in September. That's compared to just one known case in 2017. And while Eugene Police Department statistics are not specific to drug type, Eugene police Sgt. Scott Vinje said the community is just beginning to confront a growing fentanyl problem.

"We're just at the front of it, and I think it will be huge," Vinje said Friday. "It's easier to get, so I think it will take over the heroin market because it's a stronger drug. ... I do think fentanyl is going to be extremely popular."

Lewis said authorities recently seized more than a pound of fentanyl — in pill and powder form — through a series of search warrants served in Lane County after the overdose string. During the same series of investigations more than 30 pounds of methamphetamine and two pounds of heroin — along with more than 30 firearms — also were seized. Some of those weapons were stolen and destined for Mexico, Lewis said.

Several arrests were made but Lewis wouldn't further elaborate citing the ongoing investigation.

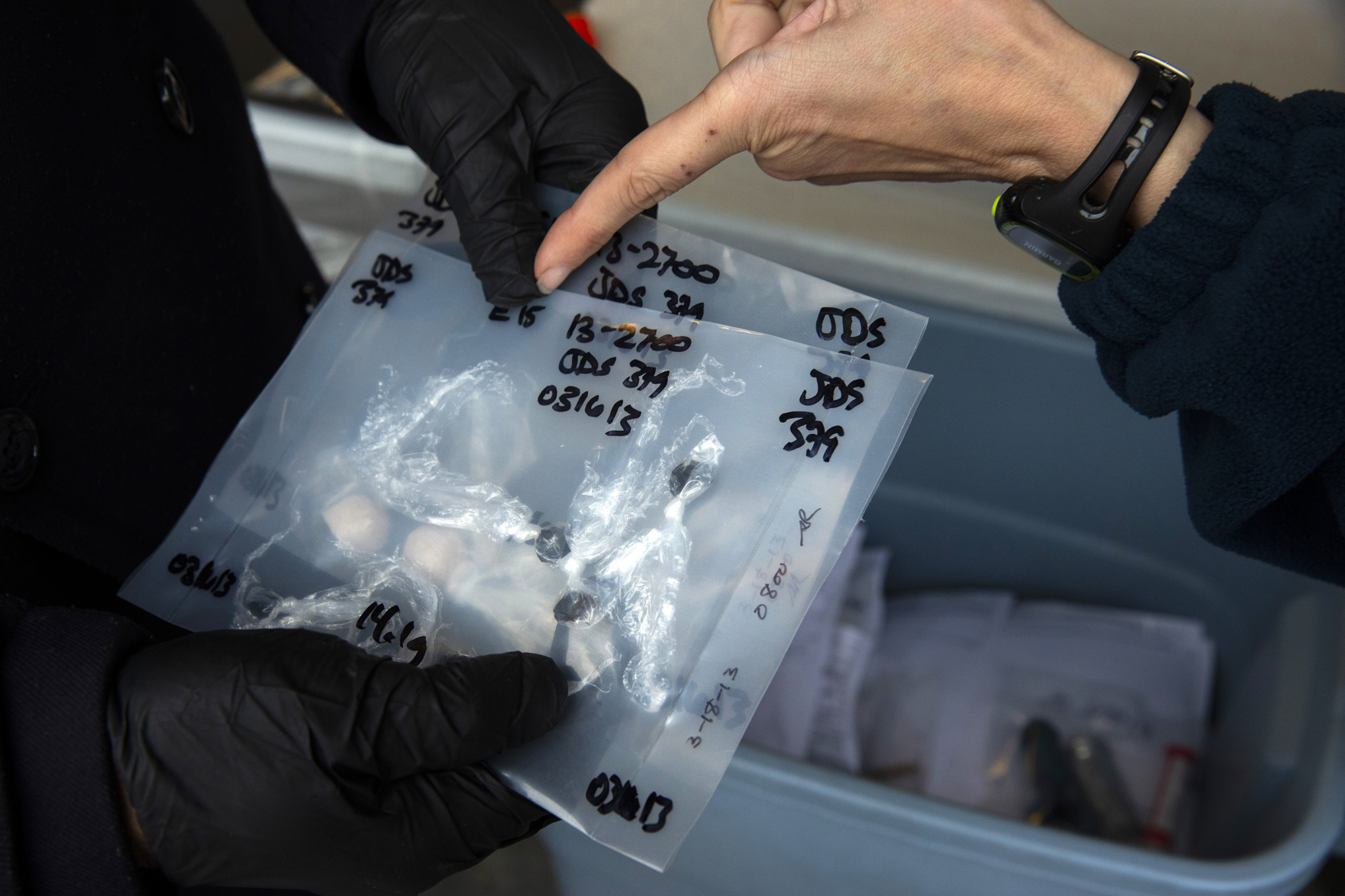

Springfield police process drugs seized as evidence for disposal. [Chris Pietsch/The Register-Guard]

Fentanyl is coming into the U.S. almost exclusively from China, available for order on "the dark web," Lewis said. Some of it also is being trafficked through Mexico.

And yet, with fentanyl use and opioid-related overdoses on the rise, countywide resources available to track and stop drug trafficking are slim after last year's disbanding of the Lane County Interagency Narcotics Enforcement Team. The unit was disbanded largely due to budgeting and staffing issues.

Now Springfield Police Department, Eugene Police Department, Lane County Sheriff's Office and other smaller agencies operate independently, Springfield Lt. Scott McKee said. Eugene police have one dedicated drug detective; Springfield police have two and a drug-detecting K9.

"INET is gone, and it would be foolish to believe that organized criminals don't pay attention to developments such as disbanding of INET, or any other regional narcotics team," McKee said.

"It's statistically too early to tell if there are more drugs on the streets, but eventually we will experience a difference because of the lack of law enforcement. We will experience a difference in illicit drugs," McKee continued.

Lewis added, "Anytime you cut back on the enforcement of drugs, which I think is the root cause of a vast majority of our crime around here," it creates a sense of freedom for criminals.

Springfield overdoses

Springfield police issued a public warning Sept. 22 after they received five overdose reports in eight hours. Last week, Lane County Health and Human Services Spokesman Jason Davis confirmed that there were seven drug overdoses reported in the first week of September; four the second week; 15 the third week; and 22 the fourth week. In October, there were eight the first week and seven the second week. The county did not have those numbers broken down by city, such as Eugene, Springfield or elsewhere.

At the time of the public warning, McKee said police didn't know if the drug consumed was fentanyl-laced heroin or something else. However, field testing later showed that the drug — purchased through a controlled buy from the suspected dealer of at least one of the 23 overdose patients — did not react like heroin. It was later tested at a crime lab and confirmed to be fentanyl, not heroin.

Springfield police carry field drug tests. The pouch contains a liquid that will change to a certain color when mixed with a particular drug. During the string of overdoses, the field tests only reacted to drugs such as heroin, methamphetamine and Ecstasy. Since that time, however, Lewis said new tests have been provided to officers that also will react to fentanyl.

During a subsequent investigation of that controlled buy, police found a gram of “China White.”

McKee said one of the September overdose victims — found in the bathroom of Target on Gateway Street — told police that he had consumed “China White.” In the 1980s, China White was a slang term for heroin but is now the term used for furanyl fentanyl, an article about the drug in Rolling Stone stated last year. China White is similar to heroin and morphine but is a hundred times more potent, produces a longer-lasting high and is more difficult to treat if a person overdoses, the article states.

The DEA cited 128 confirmed furanyl fentanyl-related deaths nationwide in 2015 and 2016, the year the drug became illegal.

None of the Lane County overdose victims died in September or October. That's because each was administered Narcan, also known as Naloxone, a medication that counteracts the effects of opioids and is available as an injection or a nasal spray.

"(It’s something) I never thought I would ever do in my career — squirt a chemical up somebody's nose to save their life because of a drug overdose,” Massey said. “But that's the measures we have to take."

Eugene police and area medics also carry the medication. Since February of this year, when they started carrying Narcan, Eugene police have used about 20 doses, department spokeswoman Melinda McLaughlin said.

Last year, Eugene police responded to 558 overdose calls — that's a 20 percent increase over the 465 overdose calls in 2016. The department doesn't keep overdose call statistics by drug type so it's not clear what types of drugs are involved. But, it appears overdose calls have seen a steady rise since 2014, when police responded to 257 overdose calls. In 2015, the number was 397.

To date this year, Eugene police have responded to 543 overdose calls.

"The fentanyl that's coming off the dark web is usually a white powder that's extremely potent, 10 times more potent that heroin," Vinje said. "Then you have carfentanil that's 10 times more potent than fentanyl. Drug dealers are loving that. Now rather than running around with a pound of heroin, you can carry just a 10th of that quantity, it's more concealable, it's cheaper, and when they cut it with something, like caffeine powder, they can build their quantity up."

According to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, fentanyl’s threat extends beyond users to others — including emergency responders — who encounter it. Touching or accidentally inhaling a small amount of the drug can result in its absorption into the body, with adverse health effects such as disorientation, coughing, sedation, respiratory distress or cardiac arrest usually occurring within minutes, the DEA said.

In a statement to public safety employees, acting DEA Deputy Administrator Jack Riley warned, "Fentanyl can kill you."

Responding to overdoses

Michael Cockerline has been a medic for more than five years in Springfield with CAHOOTS, a service of White Bird Clinic.

Cockerline acknowledges the "suspected heightened presence” of fentanyl in heroin recently but said CAHOOTS medics respond to overdose calls the same way, whether or not fentanyl is involved.

"We haven't really changed our approach a whole lot, other than just trying to be real attentive to hearing those calls come in so we can be as available as possible,” he said. “We've definitely used more Narcan in the last few months than I've seen in the five or six years I've been on the team."

Cockerline said he went on a call a few weeks ago to help a woman who overdosed in a home on what he believes was fentanyl or heroin mixed (or laced) with the drug. Cockerline said the drug’s effects were so strong that medics had to give the woman two doses of Narcan nose spray and hospital workers administered a third dose.

When a dose of Narcan is administered, he said, overdose victims often wake in an agitated state, with some upset that their high has been disrupted.

"They go from having that euphoric feeling and sensations of doing their drug to being sober. Like now," Cockerline said.

"Narcan doesn't make the drug go away," he explained. "It just blocks the drug so it's not being recepted by the body as they're anticipating.”

As a result, the user may be agitated, disoriented and even believe that emergency responders are harassing rather than helping them.

"A lot of it is a new strain of heroin that's come into town. It's got heavy traces of fentanyl in it," Springfield Sgt. Mike Massey said. "We're having our normal frequent flier heroin users tell us they're having to use just about a quarter of what they normally use and it's getting them higher than it ever has before.”

The problem, he said, is that the user who unsuspectingly takes a “strong hit” of the fentanyl-laced heroin is likely to overdose. Even if the overdose victim isn’t using alone, they often end up dumped on a corner or in some other public place by an acquaintance unwilling to call 911 but hoping someone will help the user, Massey said.

"These people aren't chemists, they're not pharmacists," Vinje said of those who lace fentanyl into other drugs. "When cutting it, they're not doing a clean blend, they're mixing it with heroin and there are going to be some areas that are super hot with fentanyl and some areas that might not have any. The user can end up shooting up with something that does nothing for them, or shooting up a super hot spot and overdose on it."

Doing what can be done

Cockerline said using with friends is the most responsible thing a drug user can do, so someone can at least witness an overdose and can call 911.

Cockerline understands he can't necessarily make someone stop taking drugs but he encourages users, who seem open to the idea, to seek treatment. At the very least he tries to encourage users to use more responsibly and safely, Cockerline said.

Dr. Charlotte Ransom, an emergency department medical director for PeaceHealth, said there is no way to use drugs safely.

"Fentanyl is not a drug we regularly prescribe, especially at the emergency department,” she said. “If it is prescribed, it's given as a patch. There are other forms, but that's the most common way it's used. ... I can't remember the last time I prescribed it to go home."

In the hospital, the drug is usually administered through an IV, Ransom said.

Overdoses on the drug look like any other opioid overdose, she said, and have the same symptoms as heroin or Oxycontin, for instance.

"Heroin always has the risk of being contaminated with all sorts of things," Ransom said. "It's an illegal drug that people mix with all sorts of things. There's no safe heroin, ever."

In her 11 years with PeaceHealth’s Sacred Heart Medical Centers at RiverBend and the University District, Ransom said she has treated many patients suffering from opioid overdoses. She doesn't believe there necessarily has been a rise in occurrences recently, as overdoses seem to "cycle in clusters."

"The most important thing to remember about opioids is if there is any concern about an overdose, call 911," she said. "Get the people there that know how to treat it because it's very treatable."

> Keep reading: On 'Heroin Hill,' drug use abates but doesn't vanish

Follow Chelsea Deffenbacher on Twitter @ChelseaDeffenB. Email cdeffenbacher@registerguard.com.