Walker's First Steps

On a warm late September day, Connor Walker, 19, lay motionless on a Connecticut football field. The St. Anselm College defensive lineman had injured his spine on an awkward block. A captain on the Marlborough High School football team before graduating in 2017, he had just started his sophomore year in college but on that day two months ago he was about to start another new journey.

Connor Walker feels like he’s floating on air. But he’s nowhere near Cloud Nine.

A spinal cord injury he suffered in a football game in late September left him without feeling in his legs. His injury, however, isn’t slowing him down.

He’s actually walking.

“You tell your brain and you tell your body to listen and it’s kind of on auto pilot,” Walker said. “I can’t feel it. It’s almost like my torso is floating, so it’s very weird.

“The best way I can describe it is floating on air.”

An awkward block

On Sept. 29, Walker, his roommate, Riley Dempsey, and the rest of the Saint Anselm College football team boarded a bus at 8 a.m. for a road game in New Haven, Connecticut.

For the three-hour ride to Southern Connecticut State University, the 19-year-old packed some snacks and a Gatorade. To beat the boredom, he and his bus buddy watched “D2: The Mighty Ducks” on Dempsey’s laptop.

“It wasn’t anything too crazy on the way there,” said Walker, a hulking 270-pound sophomore, whose major is marketing.

As a freshman, Walker started as an offensive lineman but switched to defensive nose tackle in his second season with the Hawks.

On that warm September afternoon, the game was not going as Walker and his teammates had planned. By the second half, the Hawks trailed the Owls 27-0.

During a Southern Connecticut State University offensive run play in the third quarter, the opposing center grabbed Walker by his jersey just inside of his arms.

Walker kept a low base and dipped both his head and neck downwards before an offensive guard came across and collided with Walker in a helmet-to-helmet hit. The collision bent Walker's neck beyond its normal range.

“I kind of stumbled pretty, pretty fast,” Walker said, “and that's all I really can remember up before that.”

He was knocked out.

“The best way I can describe it is floating on air.”

Lying face down on the ground after the collision, Walker finally came to about 30 seconds later. One of his teammates tried picking him up before Saint Anselm assistant athletic trainer Danny Gay asked if Walker could roll over.

“I just told him I can't feel my legs,” said Walker.

Trainers and EMTs eventually put Walker on a stretcher, rolled him over onto his back and unscrewed his facemask before taping his helmet to his neck.

“It was a really slow process,” said Walker.

His parents, Robbie and Jean Walker, watched from the stands.

Their dread growing as each second ticked by.

Once they saw their son wasn’t moving on his own, the two parents scurried down to field level where they found Saint Anselm head coach Joe Adam.

“He gives us a hug and told us (Connor) couldn't feel from his neck down,” Robbie, 51, said, “and you know just to hear that as a parent is just the last thing anybody ever wants to hear.”

Like father, like son

In the summer of 2014, Walker and his dad went to Vidal Field in Marlborough for some preseason training.

Walker wanted to prepare for his junior year on the Marlborough High School football team.

“I was in peak shape and I was a lot lighter than I am now,” he said.

Walker ran sprints while his dad timed him. At one point, the elder Walker asked his son if he wanted to race.

The two are close. And there is a constant and quick back and forth of friendly teasing.

“‘You are like 80 years old now, you’re going to break,’” the younger Walker responded to his father's challenge.

On the grass, the father-son duo lined up next to one another. But as soon as the race started, it was over.

Robbie Walker collapsed.

“I don’t even know what happened,” his son said. “He fell and he was grabbing (his leg) and originally he thought someone hit him with a golf ball.”

But the injury was more serious – a torn right Achilles tendon.

“I’m on the ground and he’s laughing at me,” the elder Walker said. “This isn’t funny buddy, I can’t walk.”

“I didn’t realize how serious it was,” said his son, who helped his father to the car.

Just over four years later, the younger Walker’s injury was catastrophic.

Lying on the football field in Connecticut that afternoon, the lineman couldn’t move.

Not fond of ceilings

Walker was placed on a stretcher and pushed into the back of an ambulance. His mother jumped in the front seat and offered encouragement to her son during the short ride to Yale New Haven Hospital in New Haven. Walker's dad caught a ride with a friend and followed closely behind.

At the hospital, doctors and nurses carefully cut off Connor’s jersey, pants and socks, and eventually took off his helmet – leaving him naked on a board – before placing him in a Johnny gown.

“I open my eyes and I kind of picture it like a movie scene,” Walker said. “… A big, bright light and just eight doctors standing over you and I was like ‘All this attention for me?’ Like what happened?”

Over the next 72 hours not much of anything happened, at least physically, for Walker. It was more mental.

He lie flat on his back and looked up at the ceiling and pondered what his future held.

He couldn’t move his arms or legs.

“It was terrifying,” Walker said. “… I hate ceilings now.”

His parents worked through their own anxieties.

“It was the fear of the unknown,” said Walker's mother, 51, “and I didn’t know what the future was going to bring for him.”

It took nearly three days for Walker to regain any minor movements in his upper body. That same day, he and his family finally received the diagnosis: cervical cord neurapraxia.

In layman’s terms, Walker suffered a concussion of the spine. It can be caused by hyperextension or hyperflexion. Connor’s spinal cord was – and still is – swollen, but intact. Despite the seriousness of the injury, he avoided full paralysis and worse, death.

“Connor was told by the doctors at Yale University that he was lucky,” Robbie Walker said. “A millimeter either way and he could have died. … It was a huge relief for my wife and I just knowing that he's not going to be the way he was paralyzed from the neck down.

“He was going to progress … and there's a light at the end of the tunnel.”

To get through that tunnel, however, Walker had some work to do.

Baby steps

When Walker was a baby, before he learned to walk, he would grab onto a nearby table to pull himself up on his two feet as he contemplated his next move.

“He always had the upper-body strength,” his mom said.

He summoned the courage to take his first steps when he was 10 months old.

“One day he let go of the table and he took a couple of steps and we were all so excited,” she said.

She experienced that joy once again on Oct. 11 – 13 days after Connor's injury.

By then Walker was a patient at the Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital in Boston where he received intensive physical therapy.

“They had him come to the doorway of his room at Spaulding and the therapist had his wheelchair behind him and a walker in front of him and she said ‘We have a surprise for you,’” Walker's mother said.

“We thought he was just going to stand up," she said. "He stood up with the walker and we all clapped … and (the therapist) said ‘No, that’s not it’ and he took a few really small baby steps and we had tears coming down our faces.

“We never thought he’d get to that point so quickly. It was pretty amazing.”

Walker’s rehab at Spaulding entailed Activities of Daily Living (ADL). This included everyday tasks such as dressing, bathing, using the bathroom, self-feeding and even meal preparation.

“Connor was able to progress through some of that pretty quickly,” said Dan Meninger, Director of Programs at Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital in Boston. “He didn’t have lingering deficits in coordination.”

Walker began to slowly regain his motor functions, balance and ability to walk, pushing a little bit further each day with the goal of getting out of the hospital.

His therapists used music therapy, an innovative form of rehabilitation, to get him there.

The music helped Walker’s body restore a movement pattern by walking to the beat of a song as he focused on the tune, and not on his legs, allowing muscle memory to kick in.

Therapists even used virtual reality. As a final step in his rehab in Boston, Walker walked on uneven surfaces such as curbs and sidewalks to replicate the real world.

After three weeks of rehab, Walker was discharged and returned to Marlborough on Oct. 25, to live with his parents and his older brother, Robbie, who is 21.

At home, Walker’s parents helped him with some of the more difficult daily tasks such as shaving and putting on his socks. They monitored him as he went up and down the stairs.

As he settled in at home, however, the shock of his injury and the realization of his current situation finally sunk in.

“In theory, it sounds great,” Walker said. “You get to stay home, relax, (and) play video games.”

But at home, he can’t use normal eating utensils. He can’t work out. He can’t drive.

A drastic change from his structured and scheduled life back at college.

“The biggest thing for me is just not being at school with my friends,” he said. “… But it’s just kind of what I have to deal with now.”

Connor Frankenstein

With the help of a cane, Walker walked into Spaulding Outpatient Center in Framingham on Oct. 31. He saw people dressed up in costumes in the waiting room. Candy filled a big orange plastic pumpkin on the front desk.

He asked his father if it was Halloween.

It was.

Someone in the lobby asked Walker what he would be for Halloween.

“Not done with the costume yet,” he said.

“He’s wearing it,” his dad added. “He’s Frankenstein.”

The pair shared a chuckle.

As Walker met some of the staff at his new rehab facility that day, he began to loosen up. It didn’t take much. He is a chatterbox and a jokester.

Later on, a physical therapist named Ashley asked Walker to roll over while he was lying down on a double-wide bed in the back of the facility. That’s when he broke the ice.

“This is weird,” he said.

“Why?” asked Ashley.

“This is the first time I’ve moved,” Walker said jokingly.

Half kidding. Half not.

Despite his struggle, the glass is always half full with Walker.

“I have the ability to sort of walk again,” he said, “and it’s only been (a little over a month) and that’s something a lot of people in this situation can’t say.”

Good luck charm

For Connor’s 18th birthday, his mother gave him a medal adorned with an image of St. Sebastian, the patron saint of athletes.

“I never wear the necklace during games,” said Walker. On the day he was injured, he had forgotten to take it off.

“I feel like it did its job,” his mother said. “I truly feel that. That’s what I wanted. I wanted that medal to protect him from harm and although he did get hurt, it could’ve been a whole lot worse.”

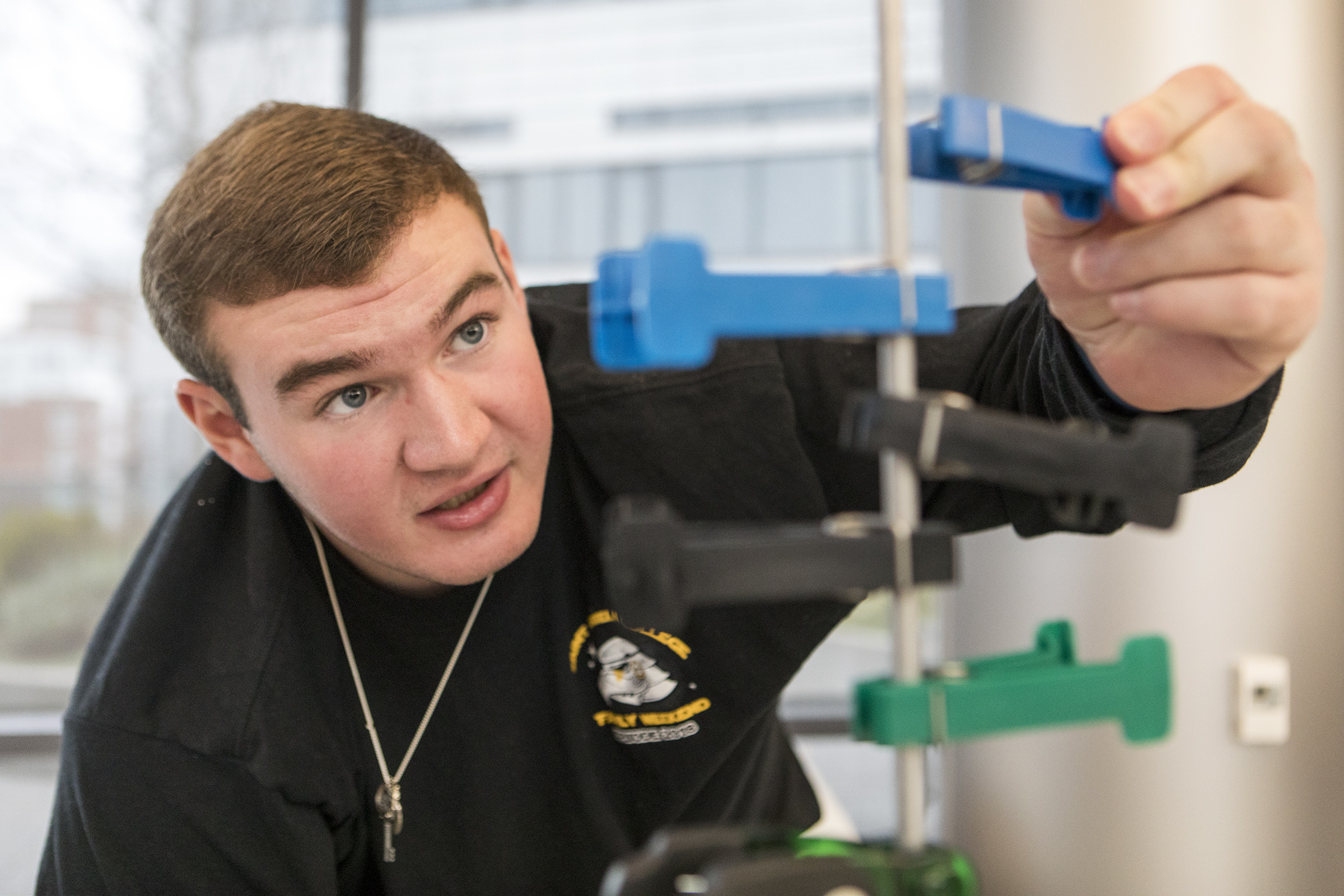

Since his injury, Walker added two special items to the necklace. A rosary ring – a gift from a relative – which symbolizes counting your blessings, and a little key engraved with the word “blessings,” which he purchased at the Spaulding gift shop the day he was discharged.

Over the past two months, Walker has also accumulated a lot of swag.

He has the aforementioned cane – with plans of “pimping” it out to go along with his 1996 Lincoln Town Car.

He has received messages of support and encouragement – and gifts – from the Boston Bruins and Boston Celtics. Even a few New England Patriots showed up at Spaulding for a surprise visit to wish him well. And the Marlborough community held a 50-50 raffle at one of the high school games and signed banners and wrote cards for Walker while he was at Spaulding.

But as he recovered, Walker knew he needed to make a special visit of his own.

An emotional return

After Walker left in an ambulance during the third quarter of the Sept. 29 game, his teammates and coaches struggled to focus on the rest of the contest.

Especially his head coach, who recruited Connor to play at the New Hampshire school.

“It was really hard, personally, for me to re-enter that game,” coach Joe Adam said. “I remember bringing our team around and I had a really hard moment when I was thinking about him and just praying that things are going to be OK.”

In the hallway of the Saint Anselm football wing, three large words are printed on the wall.

Attitude. Effort. Enthusiasm.

“He’s taken the principles of this program and applied it to his own life,” Adam said. “Now he’s seeing the progress and that’s kind of the cool bridge between football and his situation.”

Walker returned to campus on Oct. 20 for the first time since he left on the bus headed to Connecticut. Saint Anselm played Merrimack College and Walker was highlighted on the gameday program and named an honorary captain.

“It meant everything to me,” Adam said of Walker’s return. “It meant everything to me as a coach, as a man, as a husband, as a father and as a mentor. It was the most important moment of our season.”

Three Saturdays later, on Nov. 10, Connor made another trip to watch his teammates play on Senior Day against Pace University. It was the last football game of the year.

With his sophomore season cut short due to his injury and the season finished, Walker had to think about his football future.

Mainly, if there will be one.

“It really doesn't seem like something that is the smartest thing to do,” he said of playing football again, “and, I honestly, mentally, I wouldn't be able to go through it again. … And like I said, I got lucky one time and I don't know if next time, you know, I will be as lucky again.”

Just a torso

There’s a scene in the Will Ferrell comedy “Talladega Nights: The Ballad of Ricky Bobby” where Ferrell, who plays a racecar driver named Ricky Bobby, thinks he’s paralyzed from the waist down after a car crash.

A fellow racecar driver and Bobby’s pit crew chief tell Bobby that it’s all in his head and that he’s not paralyzed.

“So to prove it, Ricky Bobby takes a knife and stabs his leg,” said Walker’s father.

“He gets up and is screaming and running around and saying ‘I can walk, I can walk,’” said the younger Walker.

On his first night at Spaulding after he was transferred from Yale New Haven Hospital, coincidentally, that movie was on TV.

“So I watched it,” Walker said.

Afterward, he showed his favorite clips of the movie to his family and friends. They've used humor to combat what’s been the hardest time of their lives.

“If I didn’t know I had legs, I’d be convinced I’m just a torso,” Walker said. “… Like Centaur.”

With his football career behind him and still without feeling in his legs – Walker is thinking about his future.

And thankful he has one.

“It’s awful that it happened and I wouldn’t wish this on anybody,” he said. “But I’m blessed the way I can recover and the way I can get my mobile function back. I’m going to be able to walk again.”

Still, the timetable for Walker to regain feeling in his legs is unclear.

“I had brought his MRI over to a doctor I used to work for,” his mother said. “He told me, ‘Jean, I’m going to be honest with you. This could take up to a year for him to get feeling back.’”

Whether feeling returns to his legs or not, Walker plans on being back at Saint Anselm for the second semester when it starts in January.

“I want to get back on my feet as soon as possible,” he said, “and take back my life and become a normal kid again.”

He doesn’t want to float on air any longer.

He just wants things to go back the way they were. It may take a while, but Walker is confident he will get there.

One step at a time.

[A GoFundMe account was created on behalf of Jean Walker to help defray costs associated with Connor’s recovery.]