LOCKHART — Deputy Jay Johnson eased his police cruiser down a tree-lined Caldwell County road late at night on Feb. 1, 2018, on the trail of a stolen set of tools.

First, the rookie cop got an earful from the alleged victim, who recounted how a feud with next-door neighbor Kimberly Moore and her boyfriend had escalated into the alleged theft. Then Johnson hatched a plan, telling the man and his girlfriend he would settle things right then by going next door and recovering the belongings.

Just after midnight, the Caldwell County sheriff’s deputy stepped away from his patrol car at the side of Hidden Oak Road, clicked on his flashlight and strode toward the house where Moore lived with her mother, grandchildren and boyfriend.

He went through a closed steel electric gate marked with a "no trespassing" sign, then trudged 75 yards farther down a dusty dirt road. The beam of his flashlight illuminated a cluttered yard, a parked Ford SUV and three bare wooden steps he climbed to reach a side door of the double-wide manufactured home. As the deputy knocked, a woman’s voice called out from the darkness: "Ready to die tonight?"

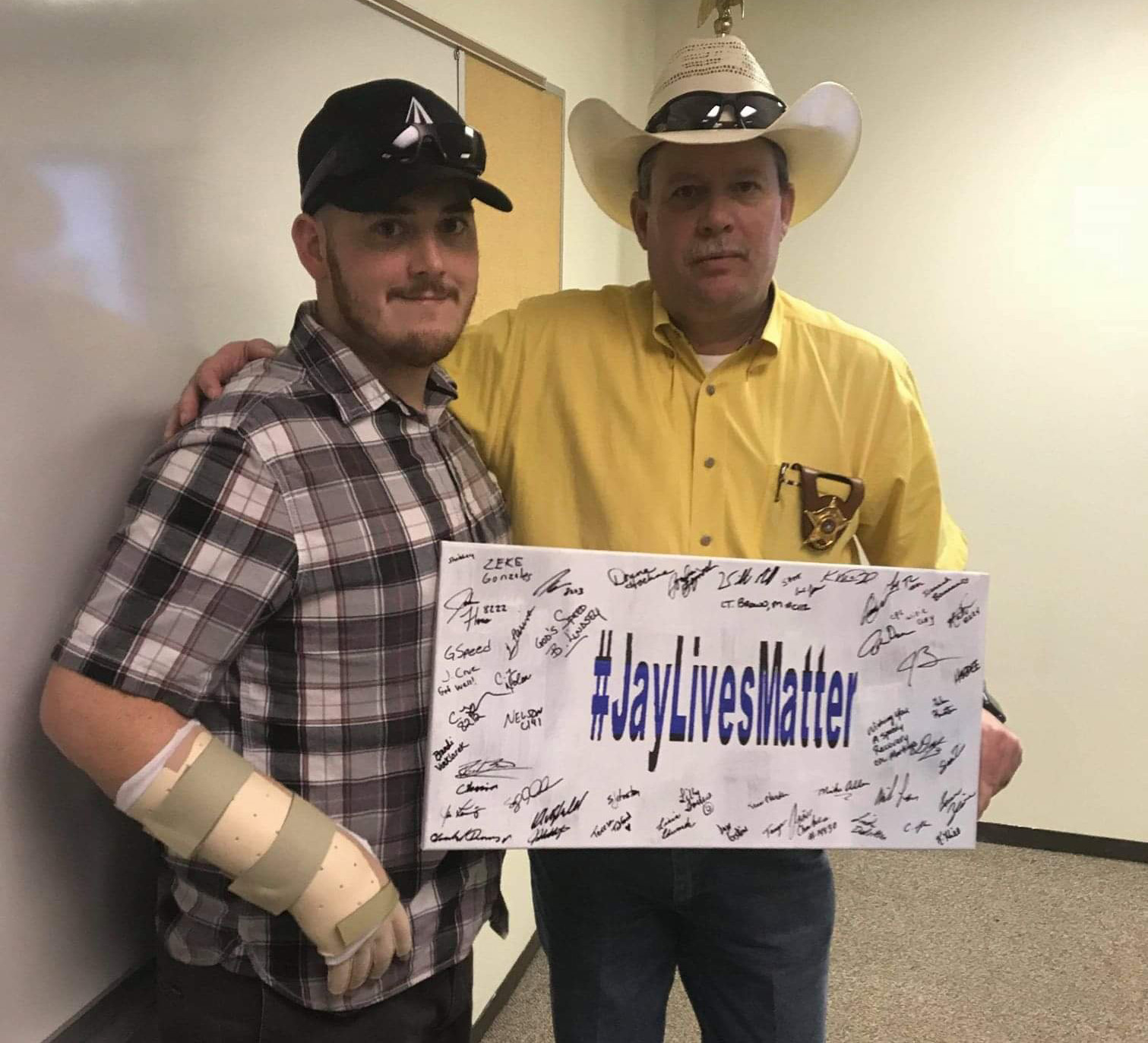

“I’ve never felt so loved because the community just came out in waves and waves of support,” Johnson recently told the American-Statesman. “There were people that I don’t know, never have known, who had reached out and were there for me.”

Amid the accolades, Caldwell County District Attorney Fred Weber quietly kept probing what went down that night. And the deeper he and his investigators dug, the more questions Weber had: Was Johnson a hero cop or a bumbling deputy who put himself squarely in the line of fire? Were Moore and Padilla a country couple protecting themselves and their ranchette from an intruder, or were they callous cop shooters?

“It is the most difficult case I’ve ever handled as a prosecutor,” said Weber, who handled major crimes in Austin and San Marcos before running for district attorney in his home county four years ago.

A year would pass before it became clear which way the scales of justice would finally tilt.

‘I will blast you away’

Johnson, now 29, wanted to become a police officer as soon as he finished four years in the Army.

The suburban Houston native enrolled in a regional law enforcement academy operated by the Capital Area Council of Governments, then signed on with the Caldwell County sheriff’s office after graduation a year later.

He spent six of his 10 months before the shooting in field training with a supervisor. That’s when Weber said a red flag emerged that should have prompted action from department leadership: In a daily appraisal of his “safety awareness,” Johnson got the lowest grade possible, and a supervisor wrote that he is “not responding to training.” Still, Johnson was released to solo patrol.

Everyone agrees that on the night of the shooting, Johnson walked into a combustible situation.

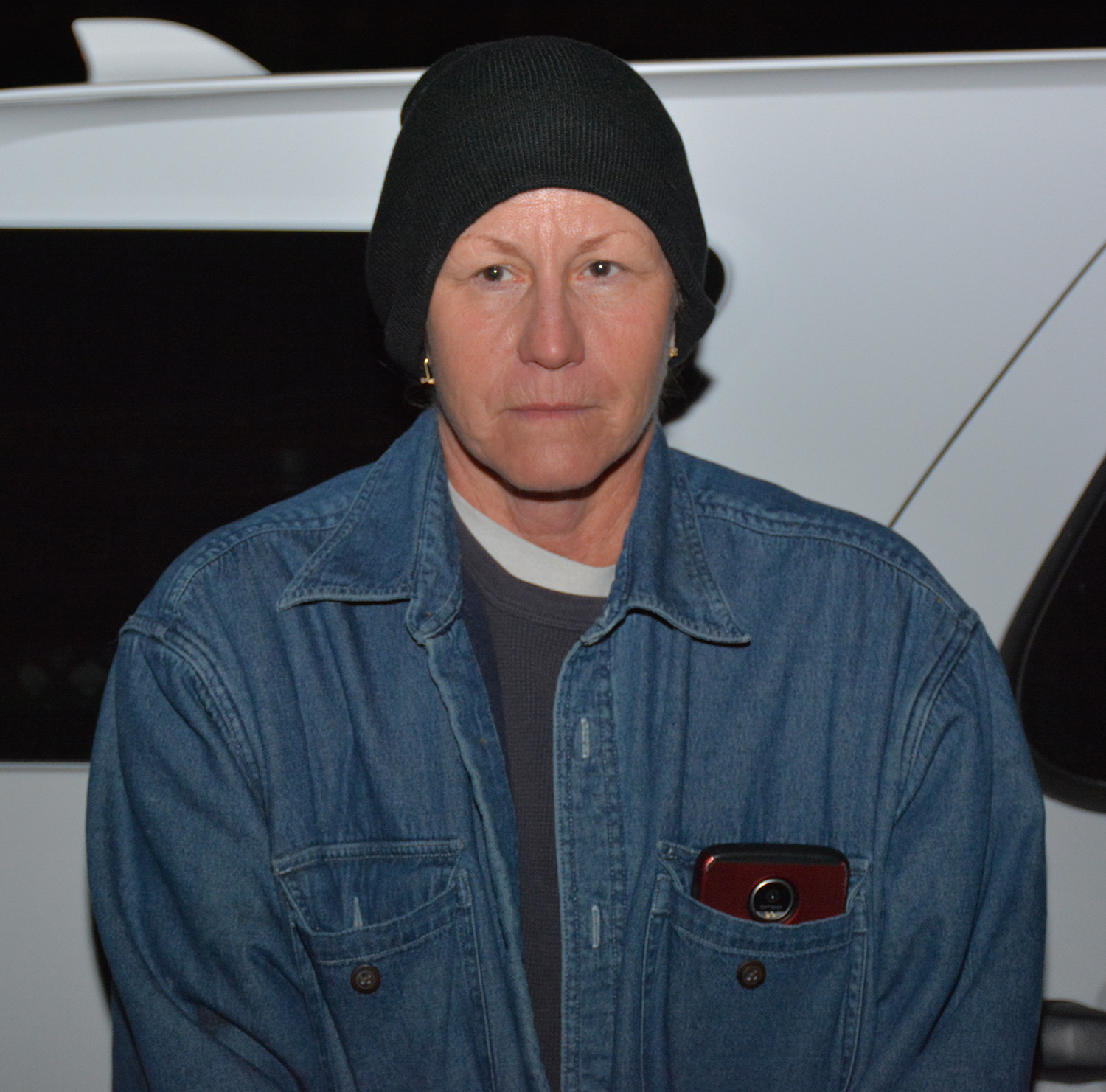

Moore, 54, and Padilla, 33, who then worked as delivery drivers for FedEx, had been having issues with their neighbor since the previous fall. They told investigators that the trouble started when the neighbors, who were renting a home on the bordering property, said Moore’s dog scratched their 7-year-old granddaughter while she rode her bicycle.

Over the next five months, relations between the families went from bad to worse.

In interviews with investigators after the Johnson shooting, Moore recounted issuing her neighbor a stern warning: “You cross this line, and I will put you down” and “I will blast you away. Don’t come on my property.”

In the days leading up to the shooting, she said she had seen her neighbor striding up and down Hidden Oak Road after nightfall, shining a light on her property. After that, she said, she and Padilla began staying up late at night “squatting on my property waiting” for their antagonist’s next move, fully expecting him to step on her land.

The afternoon before the gunfight, Moore said she heard from the owner of the neighboring property that he was evicting his tenants with whom Moore had been feuding. The property owner invited Moore and Padilla to come over, and once there, they had another heated exchange with the tenants.

Once they got home, Moore and Padilla feared the situation could escalate. They loaded their guns and waited outside.

Just after midnight, a flashlight beam appeared on their driveway. They saw a shadowy figure coming toward their house.

“Moore stated she and Padilla hid in a brush line,” a Texas Rangers’ report said. “Moore stated that as Deputy Johnson approached her residence, she and Padilla walked back toward the house.”

She told investigators that she and her boyfriend crept forward and took cover behind her mother’s Ford SUV. Moore claimed that Johnson fired first and she returned fire. But investigators say they think Moore was first to shoot.

‘This case disturbed me’

Weber was asleep when a Texas Ranger called with news that a deputy was down.

He knew it would become the latest in a series of high-profile incidents for county law enforcement. In 2016, he handled the case against a deputy who shot and killed a mentally ill man who came toward him with a farming tool. No charges resulted.

In 2017, he declined to prosecute cases against three deputies accused of assaulting a man that resulted in a $1.3 million civil verdict against the county in a federal lawsuit. A judge later reduced the amount to $605,000.

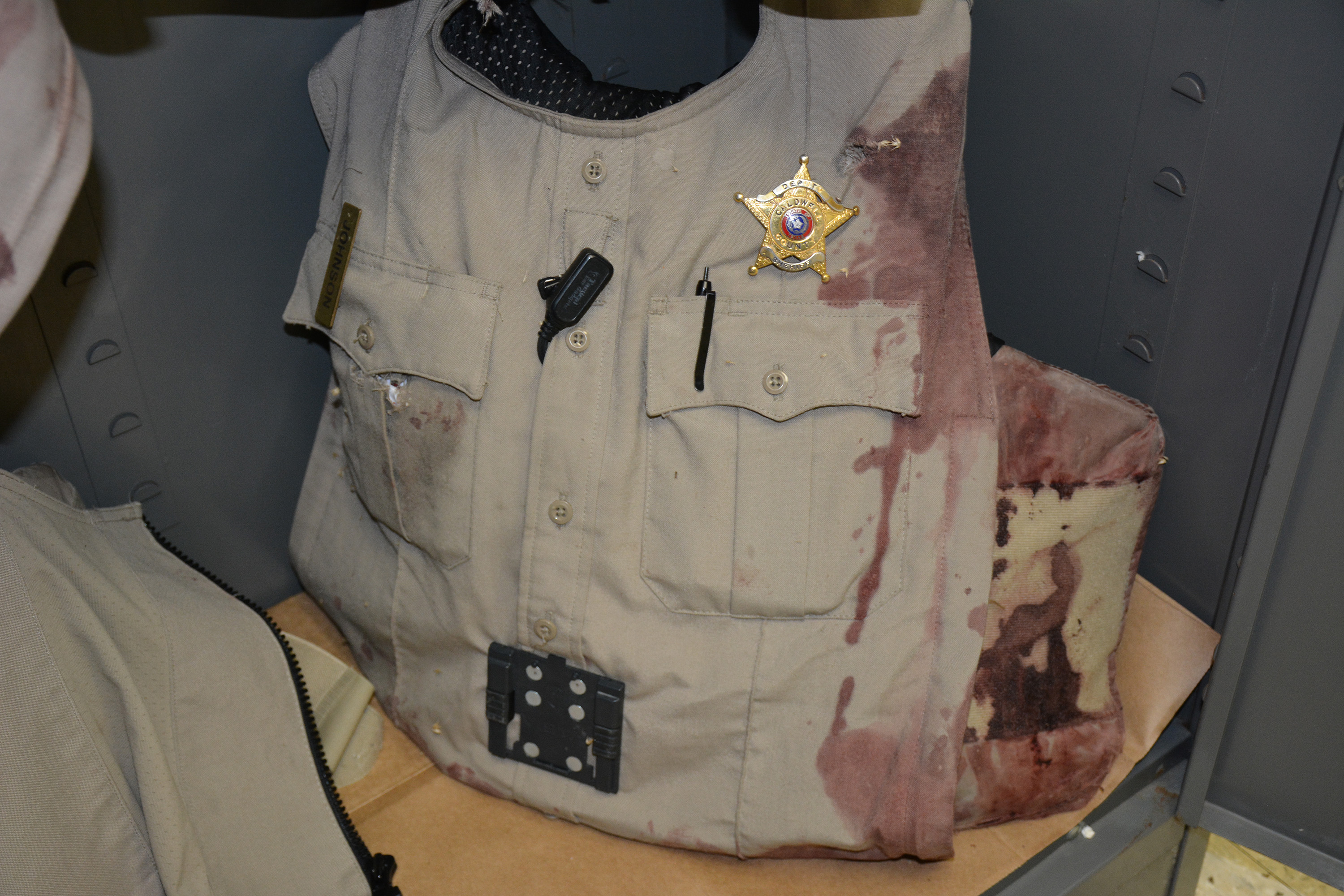

Weber drove a half-hour to the scene of Johnson's shooting. As he stared at the bloodied steps where the deputy fell and a blood-spattered pistol lying near two red shotgun shells, the district attorney liked none of what he was learning.

“From the very beginning, this case disturbed me,” he said. “It seemed like everyone exercised extremely bad judgment that night. All three of them.”

The mere fact that they had shot a deputy was enough for Moore and Padilla to be arrested and taken to jail on charges of aggravated assault with a deadly weapon.

Over the next several months, as the picture of what happened became clearer, Weber became more skeptical of Johnson. Weber said he and other prosecutors identified misstep after misstep that they think put Johnson at risk to himself and the public.

“The more I realized, there were a significant number of mistakes that were made by Deputy Johnson,” he said.

Weber said it started when Johnson first arrived on Hidden Oak Road. He did not activate his patrol car lights, signaling law enforcement was in the area. Padilla later told investigators the absence of red-and-blue flashing lights contributed to the confusion.

Johnson spent nearly two months in the hospital, thinking his shooters would face trial and an almost-certain prison sentence.

But after he was discharged, Weber called him in to a series of meetings. Johnson soon noticed a pronounced shift in tone: He no longer felt he had the hero status the community had bestowed only a few months earlier.

“It went from me being a victim to me being a defendant basically,” he said. “It went from, ‘Hey, we are going to get these guys’ to ‘Why didn’t you turn your lights on? Why didn’t you pull the car over there? Why didn’t you call for backup? Why didn’t you this? Why were all these things happening?’”

Johnson stands by everything he did. He says he didn’t activate his patrol lights because he didn’t want to draw attention to the tenants on the night of their eviction. He didn’t wait for backup because he thought the matter could be easily, and quietly, settled without a fuss.

“I was trying to handle this on the lowest level possible so that these people could go to bed, and these people could collect their belongings and move on with their lives,” he said.

By March, a grand jury had indicted Moore and Padilla on charges of deadly conduct, but it voted to not proceed on the more serious charge of aggravated assault with a deadly weapon.

As he prepared for possible trial, Weber said he found the shooting by Moore and Padilla legally defensible and believed that they did not know, could not have known, they were shooting a deputy and reasonably thought their lives were in danger. Weber said he considered taking the case to trial to let a jury weigh the evidence but thinks it is his responsibility to filter cases he and prosecutors do not believe in.

By then, he and his team said they also had begun struggling more with Johnson’s credibility and had reservations about using him as a key witness in the case.

On his application to a police training academy, the deputy said he had never used marijuana. On his application to the sheriff’s office, he said he had. (Johnson says he remembered when he applied for employment that he had inadvertently eaten a pot brownie years earlier baked by a roommate. He said he didn’t know until after he ate it that the brownie had marijuana).

In a final decision that Weber says kept him awake a week, he dropped the charges against Padilla and Moore.

“You had an officer who was shot and seriously injured, but my job is to see that justice is done,” he said.

Sensitive to how his community might react, the district attorney added a pointed message for police: The dismissal of one flawed case, he said, “does not diminish my support of our local law enforcement personnel nor discount the dangers they face on a daily basis.”

Sheriff Daniel Law has declined to comment, other than releasing a brief statement saying he supports Weber.

Johnson and representatives from the Texas Municipal Police Association are angry at how the case played out.

“It is an incredible disappointment that a citizen could attempt to kill a law enforcement officer and there is no consequence,” said Johnson’s lawyer, Tiger Hanner. “I don’t think the community supports that.”

He also issued a warning to county deputies: “It is now open season on law enforcement officers in Caldwell County.”

Kevin Lawrence, director of the Texas Municipal Police Association, added that Weber’s decision will make law enforcement work more dangerous.

A year later, Moore and Padilla are trying to piece their lives back together. They lost their jobs at FedEx and are working shifts at the local McDonalds. Both declined to comment.

Johnson remains on the Caldwell County sheriff’s office staff but is still on medical leave. Johnson said he is angry and confused by not having an opportunity to share what happened with a jury — and letting them decide who was in the wrong.

“Even though I was law enforcement, I was the victim of a crime,” he said. “I was expecting to go to trial, and tell my story. How do you shoot a cop and get away with it?”