Challenge in Hays lies in funding special education

Paraprofessional Angela Miller, left, works with STAR student Marla Tinoco-Olivas, 9, on instruction specifically designed for her academic level at Roosevelt Elementary School in Hays. [Hays Daily News]

Ask Hays Unified School District 489 superintendent John Thissen about the most significant challenge affecting Hays Public Schools in the past 20 years, and his answer is immediate and unequivocal:

“Our challenges have been tremendous because the state has not funded facilities for the most physically and mentally challenged children," Thissen said.

About 19 percent of USD 489 students receive some type of special education services, Thissen said. That compares to the state average of 14 percent.

He said there has been a lot of discussion among school superintendents in the state of “Where is the limit? We want to serve everybody, but is the majority not being served? How much is being taken from the majority? We are still in the mode of trying to figure it out — that balance.”

The Brown v. Board of Education decision of 1954 opened the door to recognizing that all children — regardless of race, gender or disability — have a right to the same public education.

The Rehabilitation Act of 1973, Section 504, addressed protections for students with disabilities in programs that receive federal financial assistance. The Individuals with Disabilities Act (IDEA), which passed in 1975, “took that further, saying students with disabilities deserve an equal education, too,” said Chris Hipp, USD 489 director of special education.

Hays is the host district for the West Central Kansas Special Education Co-operative that also serves Elis, Victoria and LaCrosse. The co-op, which has 68 certified special education teachers and staff, serves all special education students in these public schools, as well as all those in private schools.

Hipp said special ed teachers are assigned in each building, but there are also specialists who travel from building to building.

Special education serves students with intellectual disabilities, autism, learning disabilities, emotional disturbances, traumatic brain injuries, hearing impairments, visual impairments, speech impairments, orthopedic impairments and students who are considered gifted, according to the USD 489 website.

According to the U.S. Department of Education website, IDEA has two purposes: To provide a free appropriate public education to children with disabilities and to give parents a voice in their child’s education.

The law requires that all special education students have an IEP — an Individualized Education Program. In USD 489, that individualized program looks not just at performance in the classroom, it also focuses on the student’s post-secondary goals, Hipp said. “What does success for this kid look like?”

Special education funding challenges

When the state of Kansas begin closing mental hospitals, private companies, such as KVS Wheatland Hospital in Hays, came in to provide treatment options for children with significant emotional needs around 1999 to 2000, Hipp said.

But those placement options are limited. “It shifts the responsibility to the schools to meet the needs of these kids,” Hipp said.

USD 489 opened Westside Alternative School, 323 W. 12th, in 1991. Students aged 10 to 15 were referred to Westside because they had demonstrated emotional or behavioral problems serious enough to require intensive mental health services. The district currently partners with High Plains Mental Health to provide special services for students at Westside.

“School districts have to figure out how to meet the state (mandated) outcomes with a certain pot of money,” Hipp said.

That pot of money comes from three different sources.

When the federal law regarding special education was first passed, Hipp said, it promised the federal government would provide 40 percent of the funding for special education. In reality, the federal government provides about 15 percent, he said.

The state is supposed to provide 92 percent of the 60 percent the feds didn’t fund, Hipp said. In reality, “only one year in the last 10 has the state actually funded the 92 percent. It has actually funded around 80 percent,” Hipp said.

“Basically, the federal government gives us a little bit of money. The state gives us a little bit of money, and the district has to come up with the rest.”

According to the district’s website, in 2018-2019 the special education co-op was budgeted to receive $8.3 million out of the total school district budget of $49 million, or around $17 percent of the budget.

The STAR program

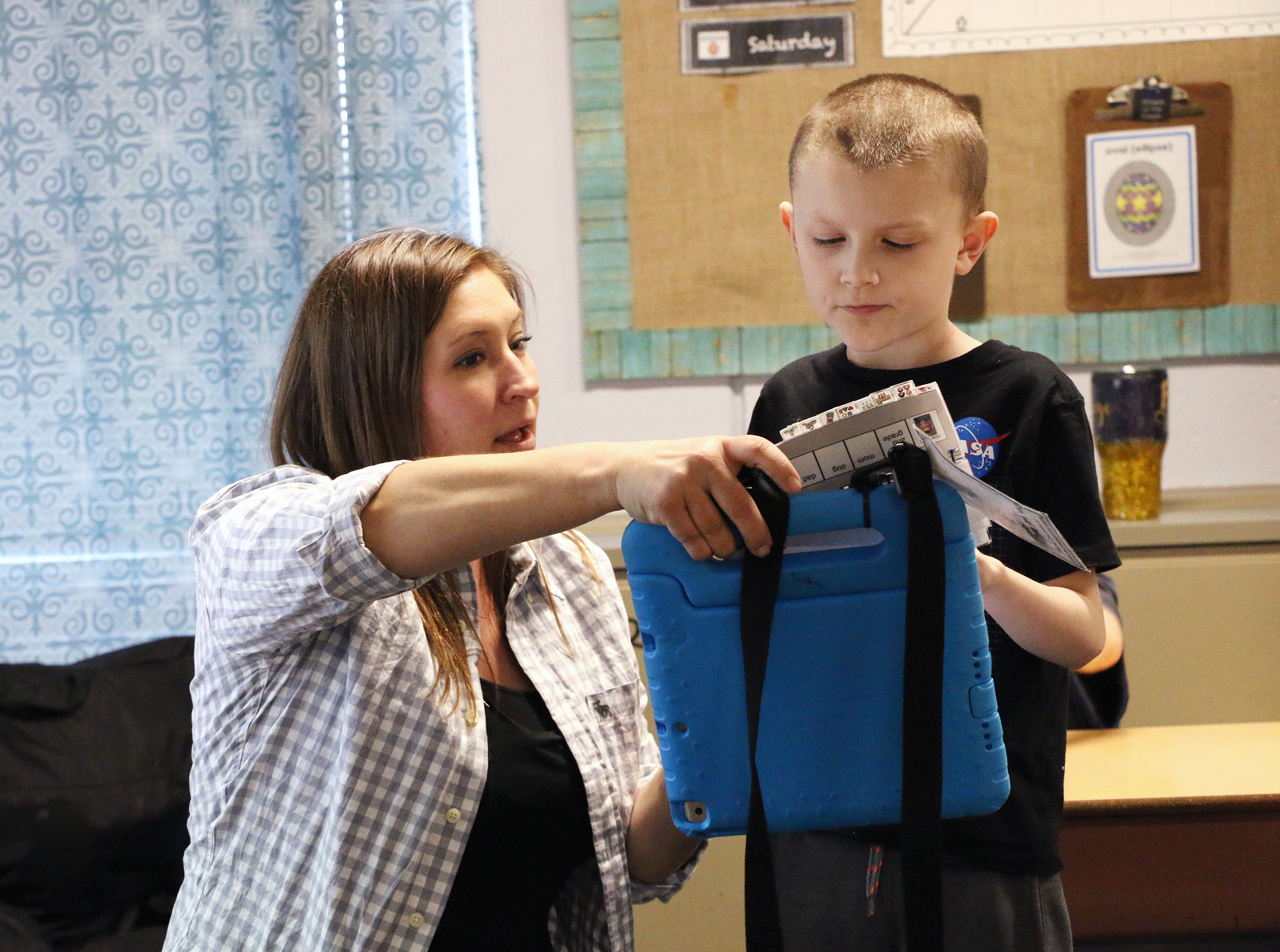

One approach that USD 489 has taken to special education has been to consolidate some special education services at one site, Roosevelt Elementary, 2000 MacArthur.

“You can be a lot more specific and focused by bringing kids together who have similar needs,” Hipp said. “It’s also more efficient.”

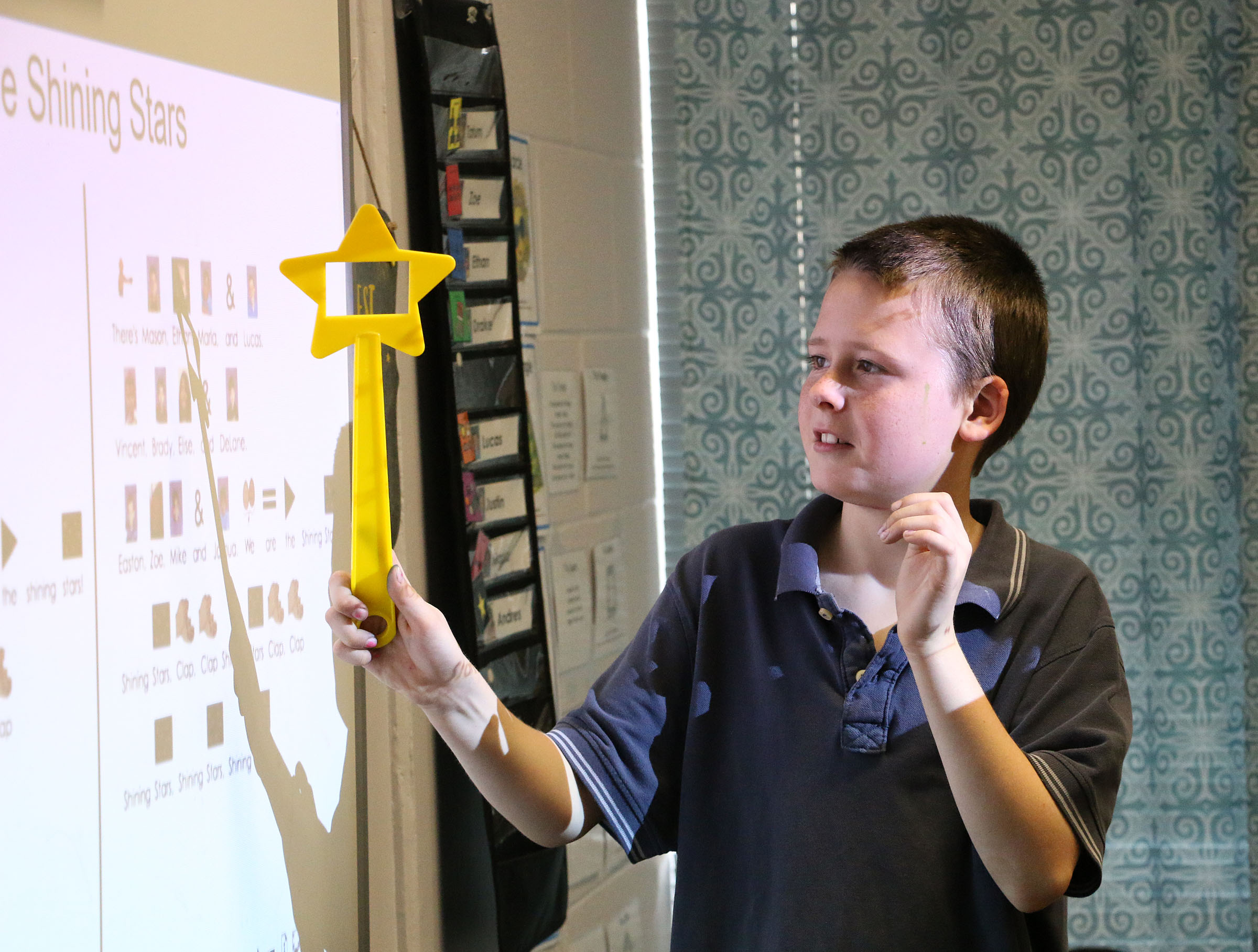

The Systematic Teaching with Adaptations and Reinforcement (STAR) program was begun three years ago by Lindy McDaniel, one of the special education teachers at Roosevelt.

This year STAR is serving 34 children, preschool through fifth grade. There are four teachers involved with the program — one specific to preschool — and the equivalent of 17 full-time paraprofessionals.

In conjunction with each individual student’s IEP, the STAR program focuses on what specifically that child needs. In addition to academics, that learning can include social skills, personal hygiene and how to follow simple directions.

“It depends on the child’s needs and what the family wants for their child,” McDaniel said.

The biggest challenge, McDaniel said, is reaching children and helping them reach their highest level of potential.

“The range of needs and abilities is so great," she said. Some students may come to us at a second grade age level, but a 6-month-old developmental level.”

Paula Rice, principal at Roosevelt, said students in the general population at Roosevelt don’t treat the STAR students as “different.”

“The most heart-warming thing for me is children don’t know any different unless we teach them there is a difference. It’s not tolerance. It’s inclusion and equitability,” Rice said.

The ABC’s of demographics

USD 489 has had a fairly stable FTE (full-time equivalency) enrollment of around 3,000 students the past few years. That figure, taken from the district’s website, includes kindergarten and at-risk 4-year-olds, but not virtual students.

In 2018 the racial/ethnic breakdown was as follows: 91 percent white, 0.2 percent African-American, 4.5 percent Hispanic and 4.3 percent other ethnicities.

That compares to the following figures in 2014, the earliest year such statistics are available: 84 percent white, 0.9 percent African-American, 9.7 percent Hispanic and 5.4 percent other ethnicities.

These figures are tracked and reported by the Kansas State Department of Education.

Sarah Wasinger, USD 489 board clerk, said in the past 15 to 20 years, the district’s Hispanic population has been between 9 and 10 percent. She had no explanation for the drop by almost half in 2018 other than that families self-report their ethnic heritage.

Historical records show there has never been racial segregation in the Hays School District. For several decades the school system has had an open district policy, “meaning families can request the elementary school they want their children to go to,” Wasinger said.

In 2018 the percentage of students who were non-English native speakers was 6.1 percent, compared to 0.1 percent in 2014. Wasinger said the most common language was Spanish, followed by Chinese.

The percentage of economically disadvantaged children in the district has remained fairly consistent in the past five years, ranging between 40 and 41 percent.

The district’s website reports that the number of students receiving free lunches has likewise remained steady the past two years at around 900 students. The number of students receiving reduced-cost lunches has been 270 in 2018-2019, compared to 319 in the 2017-2018 school year.

That compares to 896 students receiving free lunches in 2014-2015 and 350 students receiving reduced-cost lunches.

Other figures that are tracked are children from migrant families and those from homeless families.

Wasinger said migrant families are defined as those whose parents have to travel as part of their work, such as in the agriculture and oil field sectors. A special coordinator within the district is assigned to visit with each of these families and share what local resources are available to them, Wasinger said.

No children from migrant families were enrolled in the district in 2018, compared to 3 percent in 2014.

The McKinney-Vento Homeless Education Act, passed in 1987, defines homeless children and youth as “individuals who lack fixed, regular, and adequate nighttime residence.”

The federal law requires “each state to ensure that each homeless child or child of a homeless individual has access to the same education as other children, including public preschool programs.”

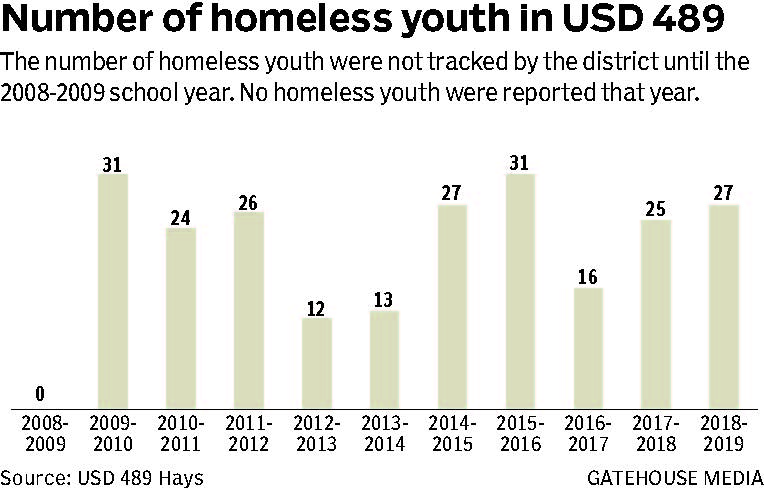

The number of homeless children was not tracked in the district until the 2008-2009 school year. No homeless children were enrolled that year. Since then, the number of homeless children has ranged from a high of 31 in 2009-2010 and 2015-2016 to a low of 12 children in 2012-2013. This year there are 27 homeless children enrolled in USD 489.