Discussion about race in schools came late in Garden City

Horace Good Middle School students fill one of the school's hallways heading to their next classes in Garden City. [Brad Nading/Garden City Telegram]

As the Brown v. Board of Education decision slowly swept integration through American schools, the path forward for Garden City, a small, rural, majority white district, was less apparent.

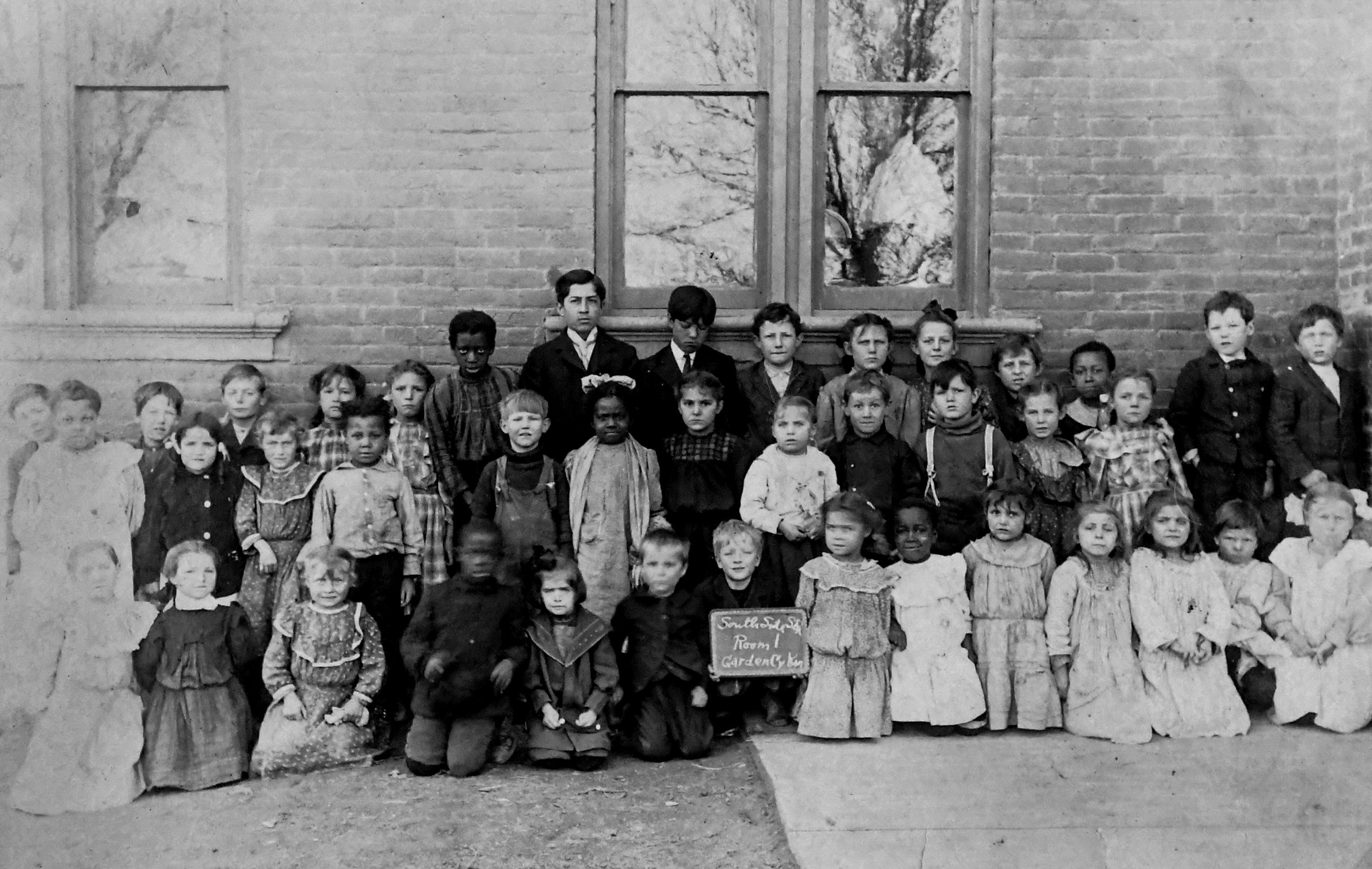

Garden City USD 457 never saw segregation — a situation not born of ahead-of-its-time progressive thinking but, as the National Park Service notes, tight budgets and few black students — and, as a result, did not face a serious discussion about the role of race in the schools until decades later.

The decision should have been one that forced communities across the country to grapple with equal rights in schools and even lead to better treatment of other marginalized groups, like Hispanic people, said longtime Garden City resident Loretta De La Rosa.

Some of that change, by no means complete but improved, has come in time for her grandchildren, De La Rosa said. But, decades earlier, as she attended Garden City High School 10 years after the landmark civil rights court case, negative or neglectful treatment of students of color was still present.

“In western Kansas, because we didn’t have a lot of black people ... they think we’re talking about everywhere else,” De La Rosa said. “They don’t see us talking about Garden City.”

Who we were

Segregation never came to Garden City’s schools, but it came to Garden City. De La Rosa and another resident, Loretta Jennings, who is black, remember realizing for the first time that sitting in the balcony at the State Theater was not habit, but effective law. Only white people could sit on the ground floor. Restaurants, businesses and, earlier, the famous Big Pool would not serve people of color.

Mike Guadian Jr., who is Latino and grew up in Garden City in the 1950s and 1960s, remembers the recreation center not allowing couples of different races to dance together at social events. Latino World War II veterans, including Guadian’s father, met with city leaders to demand equality after serving, but discrimination continued anyway.

Brown-era Garden City High School yearbooks show black and brown faces nearly lost in seas of white ones, alone, sometimes smiling, at the back of class photos, orchestra performances and basketball team group photos.

While De La Rosa, Guadian and resident Joe Gonzales, who went to Garden City schools in the 1960s and 1970s, remember positive experiences at local Catholic elementary schools, the same could not be said for USD 457.

De La Rosa said Hispanic students, many of whom worked in sugar beet fields during part of the school day, were not encouraged to succeed and many dropped out. Teachers seemed to neglect black students, Jennings said, or be harder on Hispanic students, De La Rosa said. Counselors did not present college as a real option for Hispanic students, she said. Gonzales echoed her, adding that the schools only pushed top students toward post-secondary education.

The environment was more hostile for Guidan’s parents, who would grow up to fight for equality for Hispanics in the city and school system, Guadian said. As the students of his era got older, they would push for similar change.

A changing Garden City

The latter half of the 20th century saw the exit of segregation in Garden City and a wave of new neighbors from Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia and Thailand. Meat-packing came to the city in the late ‘70s, eventually attracting Somali and Burmese immigrants to live and work in the area.

Meanwhile, Guadian and other Mexican-Americans served on a committee to bring the district into compliance with affirmative action policies — only 4 percent of employees, all Hispanic, were minorities compared to the state-required 21 percent — and fought the school board to add English Second Language classes to address high Hispanic dropout rates.

Today, according to census records, the city’s population is about 50 percent Hispanic or Latino, 40 percent white, 5 percent Asian and 3 percent African American. And after 30 years of a growing district, a steadily declining percentage of white students and steadily increasing percentage of Hispanic, black and Native American students, the white and Hispanic representation essentially switched places.

In 1988, white students made up about 66 percent of the district’s population, Hispanic students about 26.3 percent, Asian students 6.3 percent and black students barely 1 percent.

In 2018, Hispanic students made up 67 percent of the district, white students about 21 percent, Asian and black students about 5 percent each and Native American students about 1.5 percent, according to reports provided by the district.

The district today

That diversity, said USD 457 Superintendent Steve Karlin, is a “huge strength” for the district and city.

“The changes that our community went through in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s with the arrival of the beef packing industry really was a significant change in the makeup of our community, and I think since then the community has responded extremely well,” Karlin said.

Today, most schools’ demographic breakdowns reflect the district’s, with several outliers, according to state data. Two elementary schools drawing in families from outside city limits have significantly higher white populations, one breaking 74 percent. Two other elementary schools have nearly triple the percentage of black students as the district average, while two more have none. Another has a nearly 88 percent Hispanic student body.

Janie Perkins, the district’s supplemental services coordinator, said there are bilingual teachers in all district schools and 44 percent, while not necessary bilingual, are certified to teach English Second Language classes. The district employs teachers who are black, white, Hispanic, Native American and Vietnamese, and some are from Spain, India and the Philippines, she said.

Regardless, even in an ethnically diverse city, about 70 percent of all employees and 82 percent of teachers are white, Karlin said, and the vast majority of minority employees are Hispanic. The district’s efforts to groom students and other residents for teaching jobs in the district may help the administration tip those scales, he said. But, in an ongoing national teacher shortage, there are other priorities.

“We’d always like to have more qualified Hispanic teachers and leaders, but we always hire the best person for the job…” Karlin said. “Nothing is more important than that.”

According to state data, students of all races have held at least a 93 percent attendance rate since 1997, though data for black, Native American and multiethnic students is largely unavailable. In 2018, Asian students had the highest rate at about 96 percent, with white and Hispanic students hovering near 94.

The same year, white students and Asian males experienced the lowest dropout rates and white students and black males and multiethnic and white students saw the highest graduation rates compared to all other demographics.

The district and individual schools have made efforts to connect with parents of all backgrounds and promote student success, Karlin and Perkins said. The school uses Spanish, Burmese and Vietnamese interpreters, a call-in translation service and multilingual forms and fliers to communicate with families at parent-teacher conferences, in the administrative office and elsewhere.

Family literacy, math and science events are held during the school day and evening to accommodate parents with different work schedules. Some teachers go door to door before the beginning of the school year to meet parents. Several programs, like Kansas Reading Roadmap and LIFE, aim to build relationships between students, staff and parents, as well as improve literacy.

Staff at one of the intermediate schools visited Tyson Fresh Meats, where many residents work, and spoke to parents during their breaks about what was going on at the school, Perkins said. Other staff members have sat down with parents who recently immigrated from other countries to better understand their needs, she said.

What's left to do

Feelings about the district today vary from person to person.

Gonzales said USD 457 has greatly improved and has been a positive environment for his grandchildren. De La Rosa agreed that things have changed for the better, though she thinks there needs to be more teachers and administrators of color. To Jennings, things had largely stayed the same — the schools have neglected her grandchildren as they neglected her, she said.

But students see things differently. Garden City High School students Leorenz Altamirano, Alyssa Nava and Tuyen “Tammy” Truong all said the district’s free translation resources were meaningful to them.

Besides that, the high school hosts community events, like a regional Christmas celebration for Filipino-Americans, Altamirano said. Teachers and counselors treat all students equally, Nava said.

For the most part, students are happy at the schools and proud of the diversity, they said, though there is room for improvement. Nava and Truong pointed to greater diversity among teachers, Nava suggesting more bilingual staff members and Truong more Asian instructors.

And some students, though they are not the majority, are still in need of a lesson on racism and diversity, Truong said.

Since Karlin and Perkins came to the district in the late 1980s and 1990s, they said the district has worked to offer better access to students and families of all races and backgrounds. If a student or parent thinks the district is not achieving that, Karlin said he hopes they would say so to a teacher, principal or to him, personally.

“Regardless of what their background or their ethnicity is, school should be a great place for every kid,” Karlin said. “That relationship with the student and their family and understanding that is really, I think, what becomes really, really important in this. And I think our staff works very hard to meet the needs for our students and our families.”