Court nudges public schools toward equitable educational opportunity

The mural in the Kansas Capitol shown to a group of visiting public school children reflects importance of the Brown v. Board of Education decision in fostering a greater sense among the three branches of state government in terms of how adequacy and equity of state financing of K-12 education can change lives. [Tim Carpenter/The Capital-Journal]

Decades of intervention by Kansas Supreme Court justices in the state's public school system is harnessed to harsh reality that festering inequities in educational opportunity often divide wealthy and impoverished districts serving more than 450,000 children.

Lawsuits reaching the state's highest court in Kansas have exposed stark differences in strength or weakness of the property tax base in individual schools districts relative to the number of students served. This inequity of academic promise, based on zip code, can be illustrated by comparing the Burlington to Galena districts, as well as the districts in Shawnee Mission and Kansas City, Kan.

Both Burlington and Galena enroll less than 1,000 students. Imposition of 1 mill in property tax raises $496,000 in Burlington, but just $23,000 in Galena. The per-student gap is a yawning $600. A similar picture can be drawn in Shawnee Mission and Kansas City, which enroll in excess of 20,000 students. The 1-mill tax generates $3.6 million for Shawnee Mission children, but $750,000 for kids in the Kansas City district. The gap in these neighboring districts stands at $100 per student.

"That's a big equity issue," said Senate Minority Leader Anthony Hensley, a Topeka Democrat and retired public schoolteacher. "We can't leave the children of Galena behind. We've got to make sure the school finance formula treats them in an equal manner."

In response to Kansas litigation on school funding, the Supreme Court has split consideration of constitutional issues into two parts. The equity portion is defined by how tax dollars are divided among districts in the quest for balance in opportunity. The adequacy piece, which continues to vex the Legislature, refers to overall levels of funding to the K-12 system.

Rep. Russ Jennings, a Republican from Lakin in southwest Kansas, said most Kansans appreciated that generations of students living outside wealthy districts couldn't be allowed to slip through educational cracks. It's inequitable to permit students in Galena or Kansas City to suffer educationally simply because those districts cannot realistically raise local property tax revenue to match Burlington or Shawnee Mission, he said.

"Equity is important," Jennings said. "The risk is that if the equity piece goes away, everything from the right one-third of Kansas to the Colorado border is at risk."

In the past 20 years, three education cost studies authorized by the Kansas Legislature have concluded state funding didn't meet the state’s educational goals for students. Responsibility for these shortcomings has been assigned to raw partisan politics; conflicting tax or budget priorities; economic trends, including influence of a staggering national recession; and an evolving sense of what amounted to educational funding equity and adequacy under Article 6 of the Kansas Constitution.

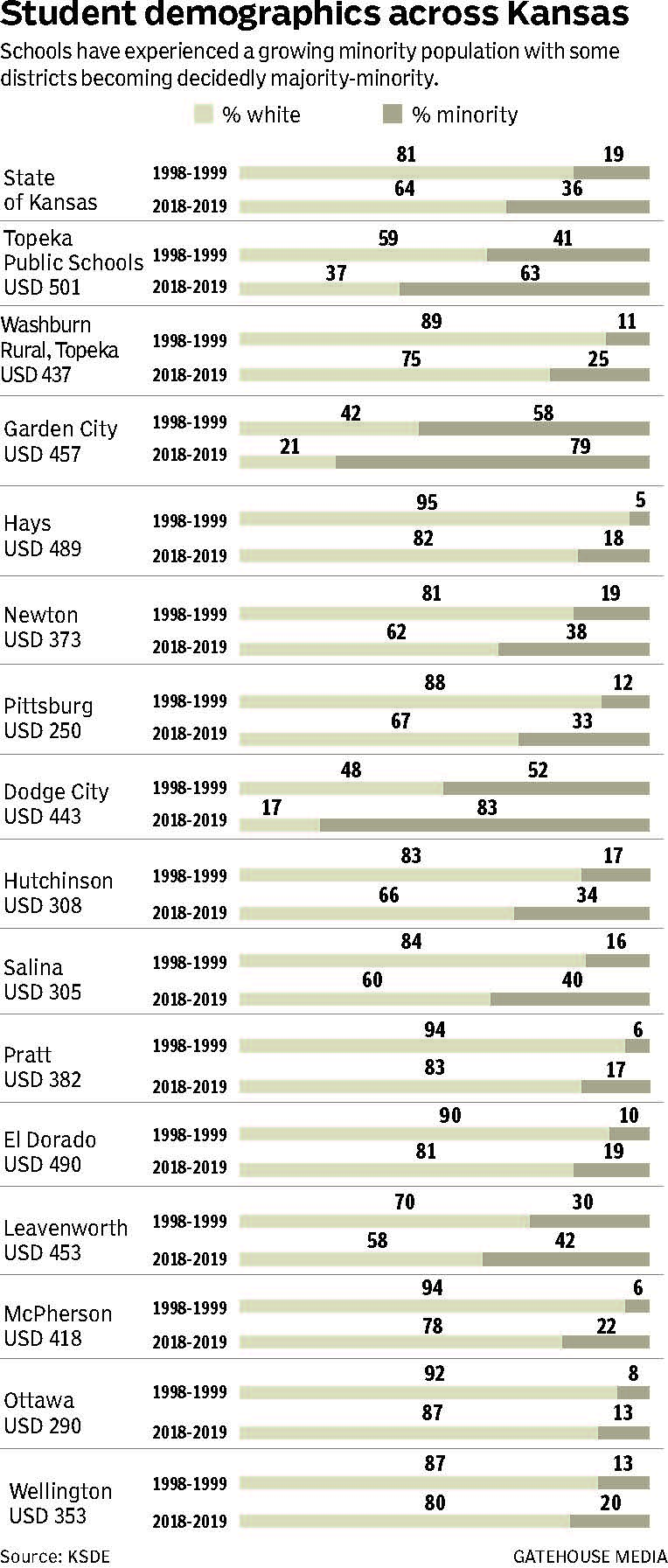

Schools For Fair Funding, a coalition of 40 school districts that includes the current Gannon vs. Kansas lawsuit plaintiffs Dodge City, Hutchinson, Wichita and Kansas City, Kan., has sought to compel massive increases in state aid to education. For the most part, the state's judicial system has sided with Schools for Fair Funding since initiation of the suit in 2010.

A three-judge panel in Shawnee County District Court found the Kansas system of funding education to be unconstitutional, which set the stage for a power struggle among the state's three branches of government.

The Supreme Court unanimously ruled in 2017 against constitutionality of a law adding $293 million over two years in state aid to the 286 public school districts. Justices lauded work by legislators to improve the state's funding formula, but the court said overall spending remained unconstitutionally low and was especially unfair to low-income districts.

In 2018, the Supreme Court accepted the five-year, $525 million surge in state spending on education. The justices said the revision dealt with funding equity problems, but the court ordered lawmakers to deal with six years of unfunded inflationary costs absorbed by districts.

Gov. Laura Kelly and the 2019 Legislature responded by adopting a new law increasing K-12 funding by $90 million annually over the next four years.

"After a significant increase in funding last year," Kelly said, "this plan addresses the Kansas Supreme Court ruling and represents what we all hope to be the final step towards fully funding our schools and maintaining adequate funding in the years to come."

House Speaker Ron Ryckman, R-Olathe, said state government had struggled to abide by financial commitments linked to attempts to bring an end to the barrage of school litigation. The new law repeats old mistakes and isn't financially sustainable, he said.

"We have a responsibility to think beyond what is politically expedient in the short term," Ryckman said. "As Kansans, we can do better."

Justices of the Supreme Court must engage in oral argument and work through thick legal briefs before issuing a ruling no later than June 30 — a decision capable of drawing to close years of caustic litigation or inspiring a fresh round of legal skirmishes.