Is Brown v. Board's legacy in Topeka fracturing?

Kim Vu, 17, hears the comments at Seaman High School: "You got an A because you're Asian."

Vu said she shrugs off the insensitive words, saying they were made by peers who haven't had much exposure to diversity in a school where 81 percent of students are white.

For diversity, she said, students should look elsewhere in Shawnee County, such as Highland Park High School in East Topeka or even Shawnee Heights High School just southeast of the capital city.

Highland Park's numbers are Seaman's reverse, with racial minorities making up 80 percent of the student population.

Angela Beraza, a 17-year-old Hispanic student, said going to school in an environment with people from many different backgrounds has been a positive experience for her.

"I think it's really good because people actually spend time with each other," said Beraza, a junior. "They're not separate."

Tyler Capps, a 16-year-old sophomore, said he has noticed "kind of standing out" as a white student at Highland Park. Capps added that he hasn't been excluded at the school, however.

Genevieve Siegel-Hawley, a professor at Virginia Commonwealth University who has researched segregation, said a concerning trend is emerging in the United States.

"Schools are resegregating along different dimensions and in different ways depending on the region of the country or the school district," Siegel-Hawley said.

That includes Topeka, site of the pivotal Brown v. Board decision that ruled "separate but equal" education to be unconstitutional. An analysis of student data found that the percentage of minority students at each of the area six high schools has increased in the past two decades though that rise is more rapid in the city's three urban schools compared to the three suburban schools.

Concentrations of certain groups "does a disservice to our democracy," Siegel-Hawley said.

"Public school is where nine out of 10 American schoolkids go," she said. "And it's the first place where they learn how to step into somebody else's shoes, how to walk alongside them, how to imagine what social policies might feel like from a different perspective. Those things are incredibly important in a society that's not going to have a clear racial majority in short order. And they're also really important in a society where inequality has become more and more profound."

Social separation

While Topeka's high schools were never segregated, separation persisted. Topeka High School had two basketball teams from 1929 to 1949, one for white students and one for black students. The team was integrated after Jack Alexander, a black student, and Dean Smith, a white student, approached the principal to say it was wrong to have segregated teams, said Joan Barker, executive secretary of the THS Historical Society.

The next year, the Ramblers and the Trojans integrated. Barker said the school also had separate dances for black and white students.

Katherine Sawyer, who is thought to be the only child to testify in the Brown v. Board case, attended Topeka High in the late 1950s. Sawyer said social separation continued to exist.

"I know when I was there, we had certain tables — nobody told you to sit in those tables — but we had certain tables that we sat in and nobody else sat in those tables," she said.

The majority of black students also congregated in a certain area of the second floor between classes and before and after school.

"I'm hearing this is still going on," Sawyer said.

Topeka's high schools have undergone a dramatic shift in demographics over the past two decades.

One of the starkest changes has been in the Hispanic population.

In 20 years, the proportion of Hispanic students at Highland Park has nearly quadrupled to 44 percent making them the largest racial group, a trend that emerged in the 2015-16 school year, according to data from the Kansas State Department of Education.

Highland Park is the only high school where Hispanic students make up the largest racial group.

"The Latino population is unevenly distributed," said Siegel-Hawley, who analyzed the data for The Capital-Journal.

Topeka West has half the proportion of Hispanic students as Highland Park though both schools are in Unified School District 501.

The typical white student in the U.S. has gradually experienced growing diversity, Siegel-Hawley said. The number of white students at every public high school in Shawnee County has declined in the past 20 years. The Capital-Journal found the percentage of white and minority high school students align with district totals.

Seaman has witnessed the slowest growth in nonwhite students. USD 345 superintendent Steve Noble said the increase has been larger in recent years and he expects that trend to continue.

"Our district values diversity in our schools, so it's great to see minority enrollment increasing over the years at Seaman High School," Noble said. "Racial diversity not only benefits students in the classroom as they learn from each other's backgrounds, perspectives and experiences, it also prepares them for the real world, after graduation, when our kids find themselves working and collaborating with coworkers from various cultures as we continue to become more globally connected."

Shawnee Heights superintendent Marty Stessman said the district's demographics reflect statewide changes in the past decade.

"Demographically, we look very similar to the state as a whole," Stessman said. "We are proud of our history, our tradition and our diversity. Our traditions are enriched by our diversity and together they make us stronger.”

Kansas' population is 76 percent white, according to the 2017 census estimate.

At Topeka Public Schools, Beryl New, director of certified personnel and equity, said the district believes their demographic makeup reflects the changes experienced in America over the past 20 years as minority populations continue to increase.

Washburn Rural superintendent Scott McWilliams and WRHS principal Ed Raines declined to comment on the high school's data.

While white students across the nation are encountering more diversity, there has also been a steady increase in the concentration of black, Hispanic and low-income students, Siegel-Hawley said.

This trend is reflected in Topeka's urban schools where the white population at Highland Park has decreased by 28 percent in the past two decades. While Highland Park's student body is 20 percent white today, 79 percent of the city is white, according to the U.S. Census Bureau's projection for 2017, illustrating a sharp deviation.

Bruce Mactavish, history professor at Washburn University, said school demographics mirror community patterns and raise questions about such structural factors as income. Seaman's demographics may still reflect an older generation of whites who moved out of urban areas, he said.

Mactavish said it is important to consider the interactions students have in formal and informal settings. Who's with whom in prom pictures? What's the cafeteria look like?

Destiny Cole, a junior at Seaman who is white, said she has friends who are minorities, but they go to other schools.

"I would like to see more diversity," Cole said. "It's good for students to be exposed to cultural diversity."

Cobe Jones, 17, who identifies as multiracial (black and white), said Seaman is "a white school, but everyone gets along."

Dalton Dunlap, a 17-year-old senior at Highland Park who is white, said going to a school with a lot of diversity keeps people open-minded.

"You don't judge as much," he said.

Highland Park student Ja'Nea Davis, 16, said she is black and imagined it would be more difficult to make friends and feel accepted at a different high school.

'Thick skin'

Sawyer's daughter, Michelle Townsend, attended school in Auburn-Washburn USD 437, graduating in 1978. (Demographic data from the Kansas State Department of Education and the district wasn't available for that school year.) Townsend became the first black cheerleader after the coach recruited her in an apparent effort to increase diversity on the team.

At times, she encountered people who would remark about her race. Townsend said she wasn't sure if some comments were made out of curiosity or ignorance.

Noticeable differences continue to exist in Topeka. Townsend said she suspects a student arriving in the 437 district from 501 would experience obstacles similar to what Sawyer faced when she entered an integrated school in the mid-1950s.

"If someone were dumped out here from a 501 school and they didn't know what they were getting into and they got out here, even today, they're in trouble," Townsend said. "They're going to have some issues. You have to get a thick skin for it."

Location, location, location

Housing is a driving force in student makeup with roots in discriminatory practices.

"The country was built on racial segregation and the housing policies that laid the groundwork for the segregated neighborhoods that we have today were all established with intent," Siegel-Hawley said. "And those housing policies and the legacy of those housing policies informs school segregation today."

Sawyer said she experienced discrimination in the 1970s when she and her husband went to get a bank loan to build a house in the county and were refused.

For families seeking affordable housing, the Topeka Housing Authority operates eight sites.

"Unfortunately a family does not have a choice of which property to live at," said Trey George, executive director of THA, Inc. "When the family comes up on the waiting list and we have a home available that meets the needs and size of the family, that is the home that is offered to them regardless of where a student goes to school."

The three largest family sites are Pine Ridge, Echo Ridge and Deer Creek. Those three neighborhoods make up half of all housing options — each is in East Topeka.

"Ideally our largest family sites would be more spread out," George said.

Four additional housing sites are within Topeka High School attendance boundaries. One other location falls into the Topeka West boundary but only has two two-bedroom units.

Several stipulations dictate where public housing can be located.

"It has to be at least 1,000 feet from a highway, waterway or railway," George said. "It has to be on a bus line and it has to be close to jobs and grocery. By the time you take all those factors and put them on a map and then look at what land is available, it greatly narrows down your choices."

THA assists about 2,000 families, totaling an estimated 4,000 people.

Policies and recommendations

Districts can promote diversity goals in a variety of ways, Siegel-Hawley said, including transfer policies. Three of Shawnee County's four major school districts accept transfer applications.

At USD 501, race is considered for in- and out-of-district transfers.

"While racial balance is not the only factor we consider, it is one that is looked at," district spokeswoman Misty Kruger said. "With that being said, we do have to make sure our schools have equal representation of racial balance and access."

In-district requests look at the diversity of the sending and receiving schools.

In the Seaman and Shawnee Heights school districts, race isn't a factor in approving or denying out-of-district transfers. In 2017-18, Seaman approved 256 incoming transfer requests, district spokeswoman Candace LeDuc said. Of those, 87 percent were white students.

Shawnee Heights district spokeswoman Tiffanie Kinsch said the primary factor in transfer applications is if the student has a connection to the district. That could be a student who moved out of the district, a student with a relative who provides before- or after-school care in the district or if parents are district graduates, she said.

Though race isn't weighed for Auburn-Washburn transfers, USD 437 spokesman Martin Weishaar said the district isn't accepting new transfer applications.

Siegel-Hawley also cited civil rights protections like diversity goals, free transportation and good outreach as important policy considerations.

None of the districts provide transportation to out-of-district students.

Districts can also reconsider their attendance and district boundaries. Some districts have redrawn their lines. Others have consolidated city and county districts, Siegel-Hawley said.

A report published by the Civil Rights Project at UCLA concluded that contemporary segregation exists not inside districts, but between districts. Its authors recommend engaging in regional collaboration to support "interdistrict cooperation."

They point to Omaha, Neb., where more than a dozen districts were combined to create more economically diverse schools.

Researchers also encourage increasing educator diversity and finding ways to keep experienced teachers in schools that are more diverse.

The "minority" population will outnumber the white population by 2045, according to March projections from the U.S. Census. However that tipping point arrives remarkably sooner for youth under age 18 - by 2020.

Faces of the fight: Katherine Sawyer

Sawyer wasn't afraid as she crossed the federal courtroom at 424 S. Kansas Ave., taking the stand to testify when she was 10 years old.

"I can remember walking up what seemed like an awful long aisle to me to go sit down in that seat up there and looking out at all those people," said Sawyer, who is now 77. "I can remember, to me at that time, that was the biggest room with the most people in it. I don't remember being afraid."

Sawyer suspects she was chosen because of the length of time it took her to get to school. As a Buchanan Elementary School student, she walked from her house through rain and snow to wait for the city bus at S.W. Huntoon and Gage. The bus would make numerous stops on the route, passing two white schools. On the way home, the bus often was packed, with students sitting four to a seat and others standing.

Sawyer was 9 years old when the case began. Her mother Lena Mae Carper, a plaintiff, also testified.

"I just remember a lot of meetings," Sawyer said.

As a child, Sawyer said she wasn't really aware that she attended a segregated school.

"You know when you live something, you don't always understand. It was normal at that time," she said.

Following the U.S. Supreme Court decision, Sawyer attended Capper Junior High School with two black boys. She was the only black girl, she said. She was also separated from many of her elementary school friends who went to different middle schools.

"It was a shock," she said. "I only had one teacher who definitely showed she didn't agree with what was going on. But other than that, I think that we all fared pretty good in that situation seeing as they weren't used to it and I wasn't used to it."

Sawyer graduated from Topeka High School.

Sawyer's children — three daughters and one son — enrolled in the Auburn-Washburn school district.

Michelle Townsend

Townsend, Sawyer's daughter, attended Wanamaker Elementary, where there was one other black family.

"The other kids were like you were some kind of odd creature or something," Townsend said, recalling that children would ask to touch her hair or skin or just do it without asking.

"All you're really trying to do, like when we moved over here with the kids, was have a decent life and send your kids, wanting them to be able to elevate themselves, that's all you wanted," Sawyer said.

At Washburn Rural High School, Townsend was part of a club created for minorities. Members would talk about issues and sponsor activities.

"There just weren't a lot of us and I guess that was to help with that situation," Townsend said.

There also weren't many teachers of color.

"I believe they should have more relatable teachers," Townsend said.

Sawyer said one teacher tried to prevent Townsend from participating in a piano competition.

"We're going anyway," Sawyer said she remembered thinking. "For some reason sometimes, they count you out as being able and capable, and that was still going on."

Townsend has contemplated the challenges she faced as a student.

"I think sometimes you think, was it a good idea that it was all integrated or should we have stayed the way it was?" Townsend asked.

Sawyer said moving into the Auburn-Washburn district gave her children "chances to do things that didn't come along in my day. But I would like to see that all this didn't matter the way it does. But it still does."

Townsend has three kids who also went to school in USD 437.

Even today, Townsend said she receives intrusive questions and comments about her identity: Do you tan? How can you have freckles? You talk white. What are you?

"Those are odd questions to me," she said. "I would never think to go up to someone else and ask those kind of questions."

Sawyer said generally society has improved overall, but there's still work to be done.

"I definitely would like to see more progress," she said. "I wish that the whole world could not see each other in colors and learn to learn from one another. If they would just sit down and talk to somebody, you would find out they're not any different than me. And maybe you have something you can give me that is good and maybe I need to hear that goodness and hear what it was for you and I can tell you what it was for me and we can stop this foolishness because that's what it is."

Nancy Noches

As a little girl in the late 1940s, Nancy Noches brought coloring books and paper dolls to NAACP meetings as her mother, Lucinda Todd, and other organizers began working on what would become the Brown case. The family's home became the group's headquarters. Their dining room table, where countless discussions took place, is part of the Smithsonian's collection.

Noches, who lives in Austin, Texas, attended Buchanan Elementary School, one of several USD 501 schools Todd taught at before marrying.

"Sometimes it was hard getting out in the bad weather to go catch the bus," Noches said. "We'd ride right past Lowman Hill school (a white school). In the summer I would go up to Lowman Hill and would play on their swings and things, but I knew that was the only time I could go up there."

One day, Todd saw a notice in the newspaper about a spring concert at Topeka elementary schools. The city's four black schools weren't included.

"That upset her," Noches said. "I remember when she got on the phone to call the board of education to see why the black schools didn't have an instrumental music teacher. She worked on that by herself for a while. And that fall, I had a violin."

After the Supreme Court decision was handed down, Noches said the phone just kept ringing. She and her mother were excited, she said.

"She just wanted everybody to have equal education," Noches said of Todd, who died in 1996.

Noches attended Boswell Junior High, which was integrated, and she graduated from Topeka High School.

Noches married a man who was in the Air Force and they had two daughters. The family would return to Topeka periodically between her husband's assignments. At one point, they moved back to Topeka before the school year was out and one of her daughters needed to complete the semester. She attended Lowman Hill.

Noches said today, people seem divided.

"Things seem to be going backwards for some reason," she said.

Marquis Burnett

Marquis Burnett remembers his father as a man who fought for justice.

"He was just all about trying to do the right thing," he said.

McKinley Burnett led the Topeka chapter of the NAACP and was a key strategist on the Brown v. Board case.

As a child, Marquis Burnett attended Monroe Elementary School.

"The black teachers were exceptional," he said.

By the time the case was filed, Marquis Burnett was in high school. He recalled how committed members of the NAACP were in the battle for desegregation.

"They had to rotate because they were getting threats and stuff, so they kind of started moving around to different people's houses so they wouldn't know what was going on," said Marquis Burnett, 79.

His father also made time to attend USD 501 school board meetings.

"They got to the place where they didn't like him there I guess, so they started having the board meetings in the daytime, figuring he couldn't come," Marquis Burnett said. "But he probably saw it coming and saved vacation time."

McKinley Burnett is quoted as saying, "Thank God for the Supreme Court," when the decision was handed down.

"A lot of people tried to get him to not go through with it," Marquis Burnett said of the case. "He wanted things to be right. Justice. There's no such thing as separate but equal."

The district's administrative center bears his family's name and a statue of McKinley Burnett was erected at 8th and S. Kansas. After a plaque is completed, a dedication date will be announced, said Vince Frye, president and CEO of Downtown Topeka Inc.

Sawyer, Noches and Marquis Burnett recalled segregation at downtown Topeka establishments.

Sawyer said she remembered having to sit up in the balcony when she went to the Jayhawk Theatre. When she and her parents went window shopping, people would scream at her father, who was white, "N-word lover."

"That went on all the time when I was a little girl," Sawyer said.

Noches recalled that she and her mother would go shopping downtown and get hungry, but they weren't allowed to eat at restaurants.

"Topeka — you couldn't do no more than you could in Mississippi. You couldn't go to the movies, you couldn't eat at the lunch counters," Marquis Burnett said.

He went on to serve in the Air Force and worked for Goodyear for 35 years. He has one son, MarYun, who has come to understand his family's influence.

"He (McKinley Burnett) was a great man, educator, he was a fighter for education and knowledge and no matter what race, color or creed you are, you should have that equal, not separate, an equal basis," MarYun Burnett said. "My grandfather and the other people in the NAACP were brave."

MarYun Burnett graduated from Highland Park in 1985. He said he loved the school's diversity and he had many friends of different races as a student.

MarYun Burnett said he believes his grandfather would be pleased with the progress that has been made, but said there are other issues like how people of color are treated by police that remain problematic. He also said McKinley Burnett would disapprove of the state's ongoing education funding woes. Last October, the Kansas Supreme Court said the school finance formula is inadequate and inequitable.

"They're directly taking care of our future," MarYun Burnett said of teachers. "I think grandpa would probably lead a march or something. He'd definitely be an advocate. He believed in education."

Related events

- A program Thursday will unveil a mural at the Kansas Statehouse commemorating the Brown decision. Gov. Jeff Colyer, former U.S. Attorney Barry Grissom, Cheryl Brown Henderson with The Brown Foundation and others will make remarks. The program starts at noon on the third floor of the Capitol building.

- Michael Toombs, art director for ARTSConnect Topeka's Brown v. Board mural project near the national historic site, will present an artist talk from 5:30 to 7:30 p.m. on Thursday. The event will take place at Bartlett & West, 1200 S.W. Executive Drive. Tickets are free, but must be reserved through ARTSConnect.

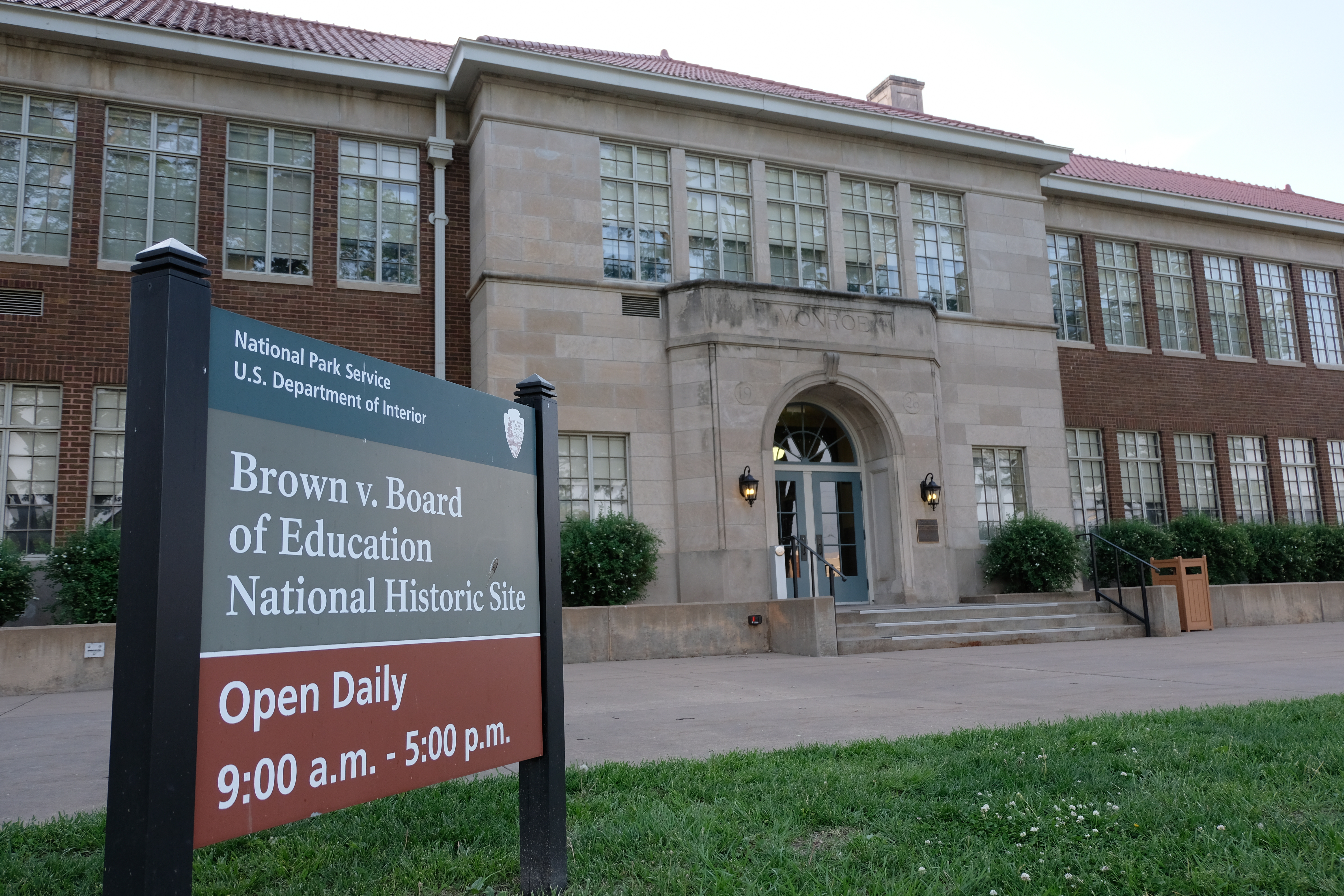

- The Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Site, 1515, S.E. Monroe, will screen the film "Someday" which is centered on school integration in Orange County, VA. The event will take place at 6 p.m. on Thursday.

- "With All Deliberate Speed: The Monroe to Sumner Story" will take place from 1-5 p.m. on Saturday, May 19. The free event will start at the Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Site. It includes a free bus tour of historical sites that played a part in the case and will feature several speakers.

We want to hear from you.

Do you have memories about attending a segregated school? Do you have a story to tell about how integration has impacted your life? Get in touch with reporter Katie Moore by emailing her at kmoore@cjonline.com.

Get more in-depth local reporting from The Topeka Capital-Journal, your community newspaper.

Subscribe