Breakdancing windmilled its way into American culture in the ’70s as one of the four elements of hip-hop culture, alongside emceeing, DJing and graffiti art. In the last decade or so, propelled by social media, the athletic dance form has exploded in popularity. Once-humble competitions have morphed into high-production, arena-filling affairs. Sponsors clamor to sign top dancers who can produce jaw-dropping video clips with viral potential. The grass-roots art form born on the streets of the Boogie Down Bronx could be an official sport in the 2024 Olympics, if it receives final approval in December 2020.

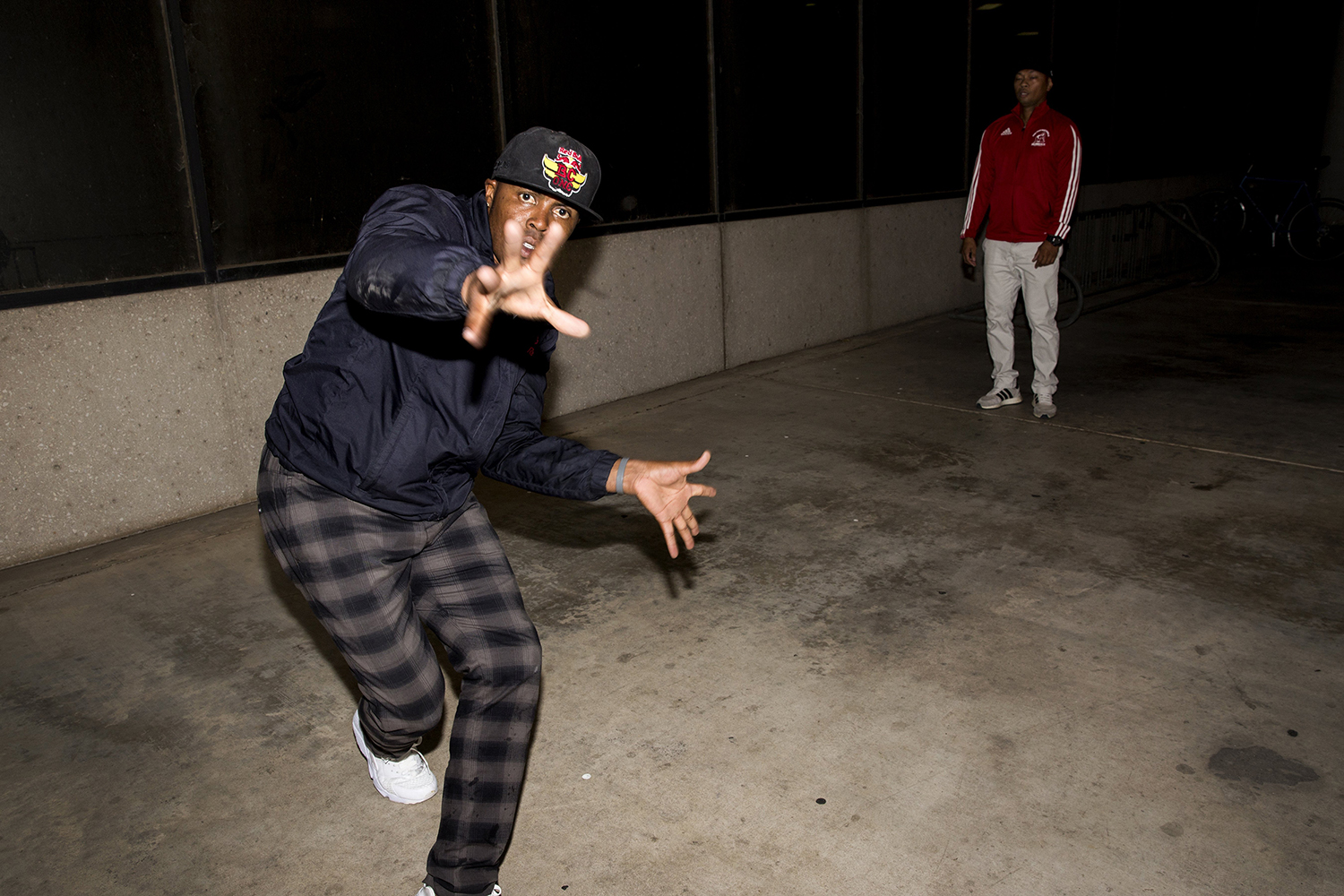

But at B-Boy City, set to go down Sept. 21-22 at the North Door, there will be no clouds of colored smoke or elaborate light shows. Crews still battle each other one on one in a circle — a cipher — like they have for the past 20 years. The air crackles with explosive energy as dancers crowd in to cheer on their crew members. They one-up each other with unbelievable feats of physical prowess, performed to the sound of breakbeats live-mixed by a team of DJs. It’s both aggressive and exhilarating, a nonviolent spectacle performed with the intensity of a gladiator sport.

Event creator Romeo Navarro once traveled the world establishing B-Boy City's sister competitions in seven countries, but now he remains close to home, devoting his life to his wife, his 7-year-old son and his service in the Manchaca fire department. Sponsors have offered to take the event off his hands, but Navarro is reluctant to hand over the reins of a competition he thinks of as “my baby.” It could be a much bigger event. It could make him a lot of money, but that’s not part of his vision.

Navarro was never in a gang, but as he came of age in South Austin in the early ’90s, gang life surrounded him. “I grew up in a poor environment. I grew up in the hood and low-income apartments,” he said.

As he moved from elementary school to junior high, many of his friends adopted gang affiliations. Though Navarro chose to walk a different path, he understood the appeal.

“Really, it was just surviving around that time,” he said. “Even just to go to school. We pretty much fought all the time.”

At 14, he was walking home from a teen night at San Jose Catholic Church with a friend when they were jumped by a group of older kids. They were outnumbered three to one, and the attack was brutal. Navarro didn’t realize how badly he was beaten until he made it home. When his mother saw him, she began to cry. To reassemble his lip, emergency room doctors stitched his face in three places. He ate through a straw for a week.

In the aftermath, Navarro's friend, driven by a desire to retaliate, joined a gang. Navarro still resisted, but not long after, he landed in trouble at school for graffiti. He was given community service hours to complete, with two options: pick up trash, or join the youth group at San Jose Catholic Church.

Though the church was the obvious choice, Navarro, still guarded following the attack, wasn’t prepared for the warmth that awaited him inside its walls. The director of the youth group welcomed him with open arms. He was immediately accepted into a club that included kids from all over the city. They agreed to let him fulfill his hours by working on production for the teen nights. He helped set up the DJ equipment and the sound system. When some of the singers who performed at the event wanted dancers onstage with them, he stepped in.

The teen nights were popular and well-attended, and the church became an oasis of creativity, away from the pressures of street life. They started hosting competitions, and Navarro began to win some of them. He began to get a reputation as a dancer, “a ghetto athlete,” he said.

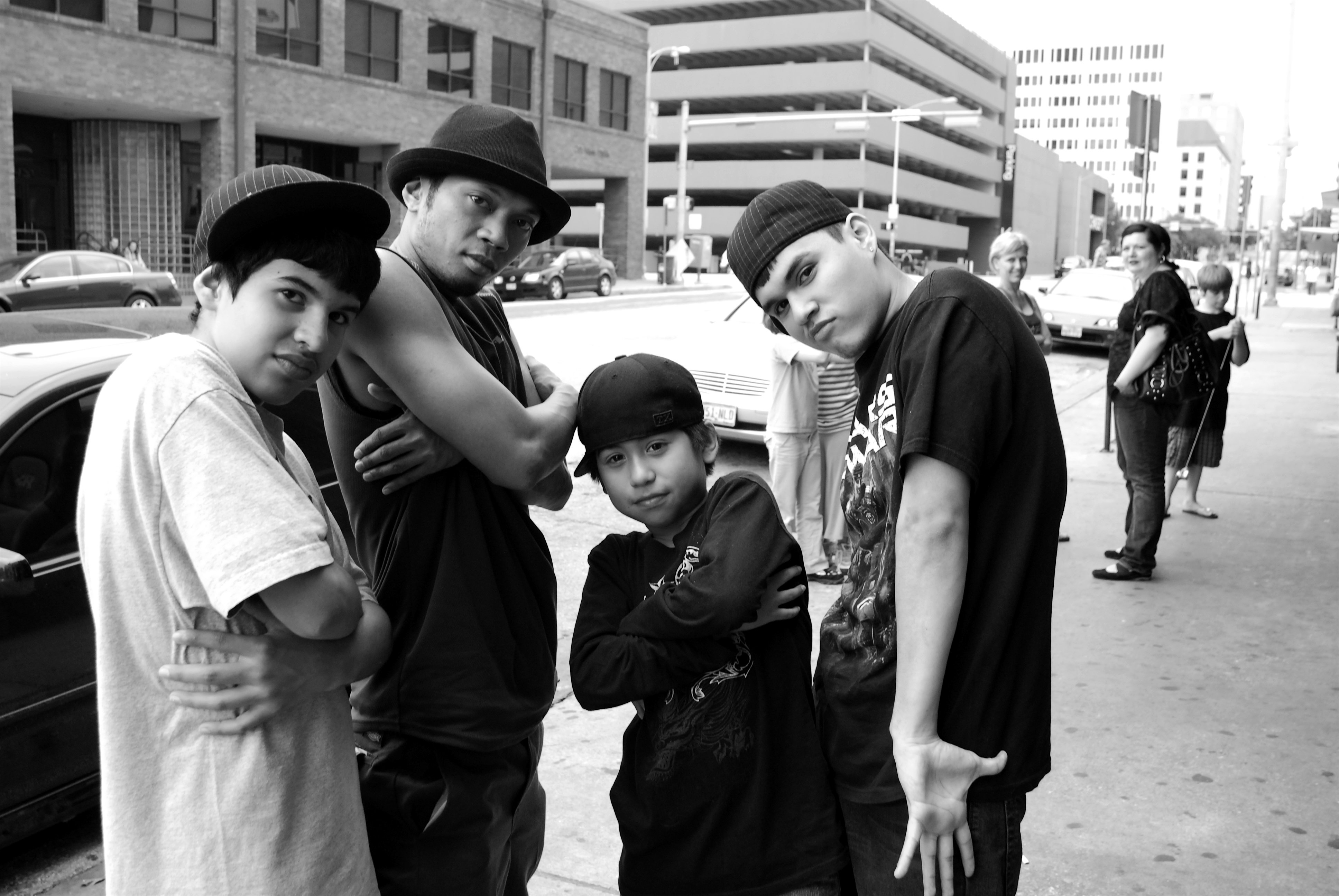

Once he established a certain “rank in the streets,” Navarro leveraged that power to shield younger dancers who ran into trouble on the streets. “Leave those kids alone, they’re just dancing, leave them alone,” he would tell their antagonizers.

After high school, Navarro left Austin to attend the Art Institute in Dallas, where he studied music and film for a few semesters. While away from home, he had a vision for how he could create “a future for our culture, just being a dancer.”

While rappers and DJs could sell tapes of their work and graffiti artists could design merchandise around their art, a means to monetize breakdancing remained elusive. He returned to Austin and started performing with breakdance crews, first C.B.S. and later Swing Team. They began to film themselves dancing, editing down performances and copying them onto VHS tapes they gave out around town. In the era before streaming, they understood the power of a moving picture passed from hand to hand.

“Everything is visual. That was our weapon,” Navarro said.

At the time, Austin clubs were wary of hip-hop, in part because of an association with gang culture. Racist attitudes toward the genre also have historically kept venues segregated.

“I told my crew, ‘We’ve got to change the way we talk to people. We’ve got to change the way we greet people. And we’ve got to change the way we dress,'” he said.

They swapped streetwear for more collegiate attire and began forging relationships with venue staff. They preached a message of nonviolence. They weren’t out looking for trouble, they just wanted to dance. And when they got going, they could make a club hype. “Because (we) were from the neighborhood, they were scared of us,” Navarro said. “We kind of broke that stigma. These guys, like they’re lions, but they’re tame.”

They danced at clubs like Catfish Station on Sixth Street and University of Texas-area dive Nasty’s, where a young turntablist named Mel Cavaricci, aka DJ Mel — who would go on to become a nationally renowned party-rocker who served as the DJ for President Barack Obama during his second term — was just getting started.

“We were all just really young and hungry. It was salad days for everybody. We were just going in hard,” Cavaricci said in early September.

Navarro and his crew established a rehearsal space in South Austin, and they began promoting their own events. Along the way, they documented everything they did.

“It’s like the way of the gun or the way of the camera, we both shoot, either way,” Navarro said. “We shoot to die, or we shoot to live. We chose to shoot to live.”

The first B-Boy City took place at the Montopolis Recreation Center in 1998. The theme of the event was a hip-hop kitchen, “food for your soul,” Navarro recalled. It was dedicated to the four elements of hip-hop. Emcees like Blakes and early standout Tee Double were in the house, and Cavaricci was among the turntablists who represented.

It “went off just with a whole lot of hands and feet, a lot of street team knowledge,” Roger Davis, who danced in a crew with Navarro and co-founded B-Boy City, said in early September.

Navarro and Davis met when Davis took a job at the rec center, where Navarro met to practice with neighborhood kids. Together they used hip-hop and dancing as “a bridge, a kind of medium just to get in these kids’ lives,” Davis said.

As they ramped up to the event, they sent their dancers out to beat the streets, drum up excitement about the event.

Word spread quickly. Young street dancers flocked to the rec center, ready to test their mettle and compete for bragging rights and cash prizes. “Hell, it was like 200 B-boys in there from all over Texas,” Navarro said.

“It was astronomical,” Davis said. “It was bigger than anyone thought it could ever be.”

Though the aggressive energy of the event scared away some parents who demanded their admission fees back, there were no fights. Navarro’s security team was made up of older kids from the neighborhood who “knew pretty much who’s who,” he said.

If they saw someone getting heated, their marching orders were to “exit them out right away and talk to them.”

“There was no 'too cool for school' element. It wasn’t a club scene. You were there because you wanted to be there,” Blakes said.

RELATED: 'What Happened to Austin?' This one-handed barber has a story to tell

Cavaricci didn’t know what to expect going into the event, and what he experienced was mind-blowing. Navarro’s crew brought in DJs from around the state, alongside California rapper Planet Asia. From the beginning, the event felt massive, and it was about to get much bigger.

“I think that has everything to do with Romeo’s tenacity. Not only as a B-boy, but also as a person,” Cavaricci said.

Navarro’s crew filmed the entire B-Boy City event. They sold tapes that made their way around the world. Isolated from the urban centers on the East and West Coasts, where older breakdancers passed foundations of the form to younger artists, Texas breakdancers were “just freestylin’ really,” Navarro said.

“I think that’s what separated us from the other areas of the world. ... We were doing our own style,” he said.

They studied classic breakdance movies like "Breakin'" and “Beat Street,” but they also incorporated moves from martial art forms, Capoeira and yoga, “everything we could get our hands on,” Navarro said.

“To me it was a street game,” he said. “It’s an American culture where we all come from different cultures and put in what we learned and what we know. That’s the beauty of being an American, you can have all kinds of flavor and put it into your style.”

Soon crews were traveling from Mexico and South America, Europe and Asia to compete at B-Boy City.

In 2001, filmmaker Marcy Garriott began following a few Texas breakdance crews for the documentary “Inside the Circle.” The film would further elevate the Texas scene when it was released in 2007.

Producer Adrian Quesada, who is touring the world selling out shows with the red-hot rock ‘n’ soul act Black Pumas, contributed to the score. He had been to B-Boy City before, and as he was working on the film, “trying to capture both the energy and pace of a B-boy battle and the emotional arc of the story,” he attended a competition.

He was struck by “how incredibly unique the scene was and how they funnel everything from passion, love, rage, aggression and art into something beautiful and positive,” he said in early September.

In 2013, Navarro announced he was stepping away from B-Boy City. The competition would continue in its other locations around the world, but he would retire the Austin event, feeling there were enough alternatives for kids. His life was going through monumental shifts. He had fallen in love and married and now, with a young son, he was determined to be the father that he never had.

“I promised my wife that I’m gonna bond with her and the baby for nine months and then a year until he’s ready to walk. If he can’t walk, I can’t walk,” he said.

He maintained that commitment, but the retirement lasted only a year.

“Some of the kids were like, ‘Rome, you’ve got to bring it back. It’s not the same. There’s other events but it’s not the same,’” Navarro said. They warned that kids were beginning to get into trouble. Persuaded by the argument, he resumed the competition, but still, he found himself searching for a higher purpose.

His friend and crew-mate, Roger Davis, had taken a position at the Austin Fire Department several years earlier. It was a natural transition for Davis, whose father was in the military.

“I came from a service family background,” Davis said. Working in the fire department aligned with his beliefs, his desire to serve a greater good.

“Not just at work, but at play, I represent something much bigger than myself,” Davis said.

He encouraged Navarro to follow his lead. The timing was fortuitous: There was an orientation for Manchaca Fire Department recruits in two days down the street from his house.

“God works in mysterious ways,” Navarro said.

Though he had built a life working with his body, the fire department’s physical test, a CrossFit-style course designed for firefighters, was the most grueling challenge Navarro had ever faced. He had eight minutes to complete it. He failed, missing the target by 24 seconds.

Still, a week later, the county chief called him in for an interview. He sat in front of 15 firefighters and talked about why he wanted to join their ranks.

RELATED: Riders Against the Storm do it for the community, the culture

He explained how his life’s work was centered on his community, “helping the youth at risk and trying to put them on the right path.”

“I grew up around here,” he said. “This is my neighborhood. I probably know everybody around here. If I’m in the front lines, I can do a lot.”

They agreed to give him a second shot. He trained harder than he ever had in his life, showing up to work out even on the days the academy wasn’t in session. When the going got hard, he thought of his son and pushed through. He was also buoyed by the support of the fire cadets who cheered him on. The camaraderie felt familiar.

“The B-boys, most of us grew up not having fathers, and we just needed to support each other in life,” Navarro said. “That’s what a crew is all about, having a crew, and that’s what the firefighters are, they just become crew.”

The next time he took the physical test, two months after his failed attempt, he improved his time by a full three minutes. He enrolled in the fire academy in January 2015.

Blakes, who works as a cultural proficiency and inclusiveness specialist for the Austin school district, runs a podcast called Hip-Hop Grew Up. He says Navarro and Davis are one of his favorite “hip-hop grew up” stories.

“You see the experiences they had in the culture informing the way that they’ve been able to transition onto other things. You can’t take that away,” Blakes said.

“Pretty much, I adapt what I’ve learned (about) how to survive in the B-boy world to now,” Navarro said. “Everything is a battle. Life is a battle. What you gonna do? Practice, get good at it? Or you gonna stay there and cry and don’t do nothing about it? What you gonna do? Just give up and die? Quit? No, you’ve got to keep living, keep fighting, keep surviving, keep learning life.”

These days, Navarro says he loves his life. “I’m forced to be physically fit, mentally fit and educated. Learning constantly,” he said.

And he loves the way his son’s eyes light up when he drives the fire truck to his elementary school for the annual fall festival. The younger Navarro dreams of becoming a firefighter like his dad, but Navarro encourages his son to keep his mind open.

“The difference is, he’s got so many doors,” he said. In his travels to establish B-Boy City’s sister competitions, Navarro developed lasting friendships around the globe. There’s a world of possibilities awaiting his young son. It’s a stark contrast to his own youth. “When I was his age, my whole world was just South Austin,” he said.

He considers the global reach of the movement he fostered a mark of his success. “To me, I made it. It’s going to continue to flourish,” he said.

One day, he hopes to hand over the reins of B-Boy City to the next generation. He’d like to see the city fund the event, which he considers “an Austin trademark.”

“People from all over the world come for that. Young folks, the future,” he said.

But for now, he’s content to run the event on a shoestring budget and serve his community as a first responder.

“I figure I’m not going to have this power or strength forever,” he said. “There’s going to be a time when I’ll be old, but I want to know that I did something this world a better place. To contribute.”