Nav & Intro

A river runs through us

The Hawk Eye | 1.28.2018

The sun rises over the Mississippi River March 12, 2015 in Burlington. | Courtesy of Alice Tjaden

The Mississippi River — the name derives from the Indian phrase “Misi-ziibi,” meaning “Great River” — curves through our backyard; flint rock bluffs carved during the Great Ice Age, a region shaped by a freeze and thaw thousands of years ago. Both lively and ancient, the river runs through us.

From the gentle beginnings when tribes of Native Americans nestled on the bluffs to the territorial rights divided out of the Louisiana Purchase, people took refuge here. A river party organized by President Thomas Jefferson and lead by Lt. Zebulon Pike laid claim to our bluff in 1805.

The natural landing of Burlington soon was bustling with steamboats rolling on the river, providing a rich history full of commerce, charm, danger and excitement that flourishes to this day.

For the next eight days, The Hawk Eye clarifies our connection to the Big Muddy through history, floods, politics, nature and fun. Are you a proud river rat? Read the stories and find out.

History

A Barge heads south down the Mississippi River near the Cascade Boat Club (before the new clubhouse was built) on April 17, 2009, south of downtown Burlington. | John Gaines | The Hawk Eye

Shoquoquon turns into Burlington

BY WILL SMITH

Before Burlington became a city, the land it now occupies was known as Shoquoquon — the Native American word for Flint Hills.

It was a land of peace and neutrality for the Native Americans who lived around it — a land abundant in the flint that was needed for everyday survival.

"The various tribes would come here, get flint, and they agreed not to fight," said Burlington historian Russ Fry.

Legend and history often intertwine, and the truth is somewhere in-between.

"I've read that (the peace between Native American tribes in Shoquoquon) may not be true," Fry said.

Of course, the history of human interaction with the Mississippi River goes back much further — thousands of years. According to Fry, the river sits on a fault line that shaped it.

"The fault caused it to sink it, creating bluffs on both sides," Fry said.

The Perfect Spot for a City

In 1805, Lt. Zebulon Pike landed at the bluffs below what would become Burlington and raised the U.S. flag for the first time on what would become Iowa soil.

It was the perfect spot for a city. While many of the bluffs made it impossible to build a town right on the river, the future site for Burlington sat right on the shore line. There wasn't much worry about flooding, either. The lay of the land kept the high water north and south of Burlington, and the rest of the flooding occurred on the east side of the river, all the way to Biggsville, Illinois.

"This was an ideal place for river traffic, which was one of the major means of transportation," Fry said. Of course, the ease of transportation was a giant boon for industry. Logs cut in Wisconsin and Minnesota were floated to a number of Burlington lumber companies. Steamboats brought in passengers and new residents.

Settlement began in 1833 after the Black Hawk War, and Burlington was booming by the 1850. It hit it's peak in the late 1800s, Fry said.

"There were a lot of people headed west who came through Burlington. In the 1850s, there would be months where 20,000 people would pass through," Fry said.

The streets were in horrible condition back then, which led to the construction of the wooden plank road. Logging was also prominent in the Burlington area, and the deforestation of the area caused the formerly mild Hawkeye Creek to flood regularly. Flash floods would swamp Division Street with little warning.

"People had to get on top of their houses," Fry said.

Burlington Heritage

Until the early 19th century, Iowa was occupied exclusively by Native Americans and a few European traders, with loose political control by France and Spain.

Iowa became part of the United States of America after the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, but uncontested U.S. control over what is now Iowa occurred only after the War of 1812 and after a series of treaties eliminated Indian claims on the state. Beginning in the 1830s, Euro-American settlements appeared in the Iowa Territory, U.S. statehood was acquired in 1846, and by 1860 almost the entire state was settled and farmed by Euro-Americans.

Subsistence frontier farming was replaced by commodity farming after the construction of railroad networks in the 1850s and 1860s. Iowa contributed a disproportionate amount of young men to fight in the American Civil War. Afterwards, they returned to help transform Iowa into an agricultural powerhouse, supplying food to the rest of the nation.

The Capital of Iowa

Burlington was the second capital of the Wisconsin territory, and the capital of the Iowa Territory after Wisconsin became a state. Not until nearly twenty years had passed was the seat of government located at Des Moines, the present site. The capital moved westward by degrees, being for some years at Iowa City.

Burlington has twice been a capital. When Wisconsin Territory, which included what is now Iowa, was organized, in 1836, its Legislature met at Belmont, a small town which would now be in the state of Wisconsin.

The capitol at Burlington was to be used until March 4, 1839, unless the public buildings at Madison were completed before this limit. But only a few meetings were held in the structure, for fire destroyed it during the second session of the Wisconsin Legislature, in the fall of 1837. Legislatures used to assemble every year, instead of every two years, as now.

After the fire the Council, as the Territorial Senate was termed, met in the upper room of a store building; the House in a frame dwelling.

The third Wisconsin Territorial Legislature also convened at Burlington, in extra session, in the summer of 1838. This session received the notice from Washington that Congress approved an act making Western Wisconsin a territory, with the name of Iowa.

After he had seen a number of towns in Iowa Territory, Gov. Robert Lucas selected Burlington as capital, until the legislature should change the location.

The first Legislature convened in November, 1838, in Zion Church. The Council had 13 members, the House, 26.

The first Territorial Legislature decided to move the capital farther west. A commission sent out to select a location in Johnson County, in May, 1839, fixed on a site at Iowa City, or City of Iowa, as it was thought the town would be called. At this time the only building in sight from the spot where the stake had been driven was a half-finished log cabin.

Gov. Lucas issued a proclamation in 1841 changing the capital from Burlington to Iowa City. Pending the completion of a capitol building, a two-story frame structure, called the Butler Hotel, was used as headquarters, and here, in December, 1841, the fourth regular session of the Iowa Territorial Legislature was held. For five or six years, however, much of the executive business was transacted at Burlington.

Iowa became a state, with Iowa City the capital. But there was a feeling the seat of government should be near the center of the area. Des Moines was selected for the honor, and in November, 1857, the state effects were moved from Iowa City and the old capitol, to the new capitol, then hardly more than half finished. It was not until the close of the year that the last loads of State goods — in bobsleds drawn by oxen — reached Des Moines.

Snake Alley

Commonly known as the "Crookedest Street in the World," Snake Alley has been a source of tourism pride since it was constructed in 1894.

The physical limitations and steep elevation of Heritage Hill inspired the construction of Snake Alley. The alley was intended to link the downtown business district and the neighborhood shopping area located on North Sixth Street, of which Snake Alley is a one-block section.

Three German immigrants conceived and carried out the idea of a winding hillside street, similar to vineyard paths in France and Germany: Charles Starker, an architect and landscape engineer; William Steyh, the city engineer; and George Kriechbaum, a paving contractor. The street was completed in 1898, but was not originally named Snake Alley, as it was considered part of North Sixth Street.

Some years later, a resident noted that it reminded him of a snake winding its way down the hill, and the name stuck.

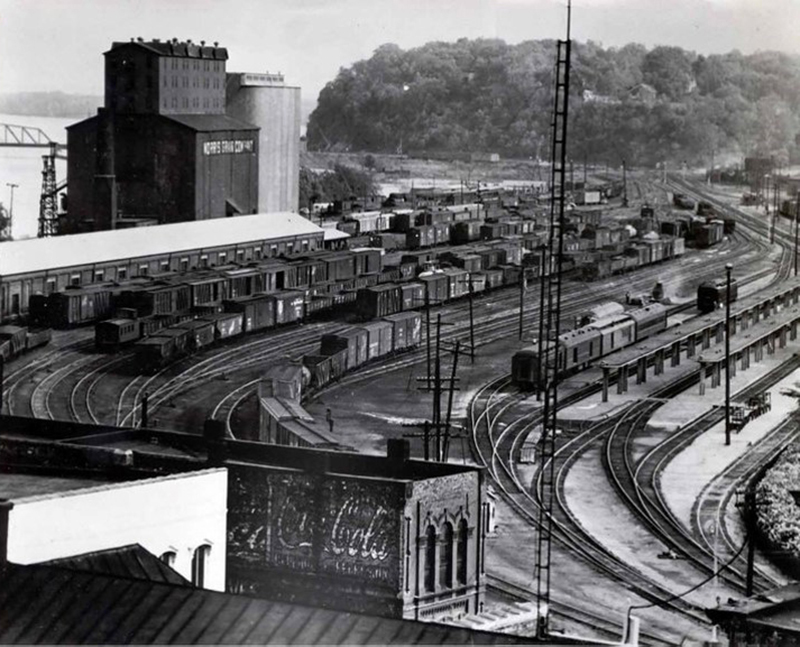

Rail Bridge and MacArthur Bridge

The railroad bridge across the Mississippi River between Burlington and Illinois has been a fixture of the landscape in 1868, and has been rebuilt twice since opening. The first was a single-track bridge that opened in 1868, and the second, a double-track bridge, was built in 1893.

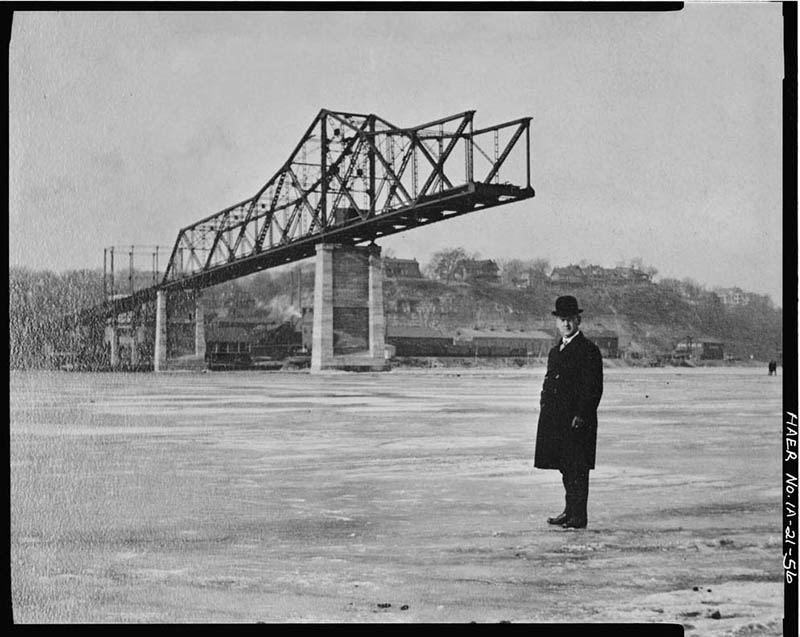

While the Great River Bridge has only been around for the past 25 years, the bridge that was there before — the MacArthur Bridge — had a history that reached back to 1916.

Replaced by the Great River Bridge in 1993, MacArthur Bridge generated millions in toll revenue by the time it was closed and dismantled in 1993. The bridge operated for 76 years, closing less than a quarter century short of its 100th birthday.

Nicknamed the “Golden Goose,” the MacArthur Bridge was constructed between 1916 and 1917, and stayed active until Oct. 4, 1993, when the Great River Bridge opened to take its place. For a short while, they existed side-by-side.

“I crossed that bridge thousands of times, and when it was replaced, we did a lot of work on the replacement bridge,” said Mac Coffin II, owner of Frank Millard and Co.

The Great River Bridge carries with it the Frank Millard legacy, which seems appropriate. MacArthur Bridge’s namesake is taken from John A. MacArthur, who developed an innovate financing plan to convince city leaders how much the bridge was needed. MacArthur, a son-in-law of Frank Millard who led the company into the coal industry, is Mac Coffin’s great-grandfather.

Though Coffin never had the opportunity to meet his great-grandfather, he moved into the man’s historic home about four years ago.

“When I was a kid, my parents had free passes to cross (MacArthur Bridge) in the 1950s. But that stopped,” he said.

Boating and skating

Despite popular misconceptions, people in the 1800s didn't work all the time.

They liked to play, too.

"The river was always a big part of recreational life," said Lindsey Schier, co-director of the Des Moines County Heritage Center. "You would have kids and adults who used the river for ice-skating. There was even a slide that went into the river in 1902."

Only the bravest skaters ventured out to skate on the Mississippi, and a few broke through the ice and drowned in the river.

The first ice skating rink in town, Champion Skating Rink, opened in December 1866 at the foot of Jefferson Street. But most preferred using the river over the rink, and it eventually closed. Other rinks also were unsuccessful due to a preference for skating on the river, until Lake Starker in Crapo Park opened up for the youth.

Boats can be just as fun, though, and Burlington was teeming with boat clubs.

"These places (boat clubs) were also social clubs. The Burlington Boating Association, their annual ball was one of the biggest social events. But you had to be a member or know a member to get a ticket to the event," Schier said.

Afternoon and evening boating excursions were quite popular throughout much of the mid to late 19th century. In the 1880s, boat clubs were so popular folks could charter a boat any time they liked.

"The Boat Club Band was one of Burlington’s leading musical organizations for many years. Other organizations include the Cascade Boating Club and the North End Boating Association," Schier said.

Cascade Boat Club

The Cascade Boat Club was founded in 1890 and located on the south side of Burlington. The 1888 bylaws indicate that the purpose of the organization was to promote hunting, fishing, shooting, and boating among its members and all citizens in the Mississippi River Valley around Burlington. It was also to maintain a club house and promote and manage social and recreational activities for its members and their guests.

One of the fundraisers for the organization was a shooting event that was held on Thanksgiving Day. This evolved from a turkey shoot to trap shooting. Later on this event also coincided with a feather party.

Feather parties were used by many organizations as fundraisers. These events were meat raffles. At the earliest feather parties, attendees had a chance to win turkeys, chicken, geese, or ducks; hence the name “feather party.” Eventually, other types of meat also were part of the event. Attendees would buy raffle tickets or enter drawings for a chance to win one of the prizes.

Building boats

Master boat builder James Jordan died in 1939 in Burlington, but built quite a few boats before he did. He, along with local jeweler Charles Walden, promoted one of the first boat races held in Burlington in 1869.

"He was an avid rower himself, and competed in many boat races," Schier said.

Jordan primarily built the more rounded St. Lawrence skiffs, and transitioned to flat bottomed boats that were more common in Burlington. He built more than 150 boats, starting in 1860.

Jordan competed in boat races and also won a few wagers. In his early 20s he and a friend won a $10 bet by beating out two members of the Burlington Boat Club. This race was 1 1/2 miles upstream and three-quarters of a mile with the current. Jordan and his partner finished in 13 1/2 minutes, and the representatives of the boat club came in a minute behind them.

Drinking and eating from the Mississippi River

The nice thing about a river is that it provides most of what the average person needs. Food. Water. Recreation.

Thanks to the industrial-scale ice harvest of river ice, the Mississippi played a part in cooling down drinks on a hot summer day. But those drinks didn't always taste the best — unless you like dirt and debris in your ice cubes.

"The city eventually put in sanitation regulations on the purity of ice that could be sold," Schier said. "There was so much debris that washed down the river, you couldn't use it (ice) for anything other than putting it into an ice box."

The Mississippi is also perfect for hunting and fishing — even in the winter. A January 1852 newspaper article stated that the ice fishing in Burlington was “excellent.” In the 1840s, there was a claim that a 40-pound salmon was pulled from the river, and catfish could weigh as much as 175 lbs.

Big Slough was a one of the most popular fishing spots in the area. Perch, bass, salmon, and catfish were all common. Fish were so plentiful in the 1880s that sportsmen would use artificial lures over live bait to create more of a sport.

Ice Harvesting

At its peak, the American ice industry would be recorded harvesting around 8 million tons of frozen water annually, of which around 3 million tons would account for melt loss while awaiting sale.

Harvesting at this time took place primarily along the banks of the Hudson river (near New York), where over a 150 mile stretch, 135 ice houses could be found (an average of one every 1.1 miles of coast). The industry's first major supply crisis arrived not due to warm winters or from the invention of commercial ice machines but rather pollution from one of the world’s fastest developing cities — New York. Regardless, ice harvesting would last as late as the 1950s and establish a global revolution for the chilled drink.

A Gentle Decline

It was the river industry that made Burlington. And it was the lack of river industry that started the city's decline in population. A decline that continues to this day.

Fry pointed out two major events that reversed Burlington's fortunes. The advent of the railroad, and the advent of corporations.

"Initially, the railroad allowed farmers to send their goods, livestock and grain out, so money was pouring in. It was the late 1800s, and Burlington was in it's heyday," Fry said.

Back then, corporations were formed for a single task — such as building the railroad bridge in Fort Madison — then disband when the mission was complete. That changed after the Civil War. Corporations became permanent, funded by the kind of cash that encourages monopolies.

"You could have a huge brewery in St. Louis and ship beer all over the country on rails. It would be cheaper than making the beer in your hometown. The money started going out of town," Fry said.

Progress continued to roll through Burlington, and not always for the better. Construction of the river levees began in the early 1900s, which caused persistent flooding in Burlington that continues to this day. The largest of the those floods —the Flood of 1993 and the Flood of 2008 — crippled Burlington's downtown for months and caused millions of dollars in damage.

But all hope is not lost. Fry said the Iowa Army Ammunition Plant helped the town survive and the Case company on Burlington's north side is a big employer, as is Great River Medical Center and General Electric. Over the past few years, downtown renovations have turned Jefferson Street sidewalks into social spaces.

The past of the river is set. But not even the encyclopedic Fry can see its future.

Great River Bridge through the lens

The Great River Bridge opened Oct. 4, 1993 and replaced the old city-owned toll-operated MacArthur Bridge. The five-lane cable-stay bridge spans across the Mississippi River from Burlington to Gulfport, Illinois. It has become a visual icon for the city of Burlington.

![Brian Cosgrove of McClain & Co. out of Waterloo works from a bucket truck over the Mississippi River inspecting the underside of the Great River Bridge April 12, 2013 in Burlington. [Brenna Norman/thehawkeye.com]](https://stories.usatodaynetwork.com/ariverrunsthroughus/wp-content/uploads/sites/44/2018/01/Great-River-Bridge-011.jpg)

Photography

The sun rises over the Mississippi River March 13, 2015 in Burlington. | Courtesy of Alice Tjaden

Photographer captures river's beauty at every sunrise

BY JULIA MERICLE

The first thing Alice Tjaden does every morning is look out her window to see if the sky over the Mississippi River is cloudy or clear.

Tjaden has been taking photographs of the sunrise over the river almost every morning for the past five years.

Equipped with a camp stool, two cameras and a cup of coffee, she captures the quiet moments of early morning while most of her neighbors are still asleep. The first flecks of sunlight glitter on the water.

Tjaden snaps her camera at the same time and in the same location nearly every day, but somehow she comes away with hundreds of unique photos. The sun and the river never look quite the same, she said.

Her best shots make it onto the Pictures of Burlington Facebook page, to share the beauty with over 11,000 members of the social media group.

Tjaden does not have to travel more than a few steps for her photography. Her backyard overlooks the expanse of water beyond a short, stone wall and framed by trees. Once covered in leaves, the trees now sit bare, their silhouettes still beautiful against the dark, early morning sky.

As she holds her camera to her eye, birds flit through the frame. Geese and gulls fly over “big island,” and if lucky, she captures an eagle mid-flight.

Tjaden said as the seasons change, the sunrise moves across the sky– in the far left of her yard in the middle of the Summer and in the far right by mid-Winter.

Her ideal circumstance for good photos is when there are a few clouds, the river is absolutely still, and when the sun comes up it turns the clouds into reflections on the water.

Tjaden often takes photos during the 30 to 45 minutes before full sunrise, just as the first spots of pink start to appear on the horizon.

“When it starts up you see a little bit of color, and a lot of times, when the clouds are up above it, the sun starts going up and all the clouds turn red,” Tjaden said. “Sometimes when everything is reflected on the river and everything on the sky it makes you feel like this is all one and you are part of it.”

Some days the sun paints a gold streak across the water. Tjaden has been trying for a while now to capture a towboat going through this “golden path.”

Other days puffy clouds cover the morning sky, and rays of light shoot through whatever spaces they can find making the “Jesus picture,” as Tjaden’s children called it when they were younger.

Tjaden has always taken photos, but they were not always of sunrises over the Mississippi River. She originally learned on a Brownie camera, and the switch to digital and its ability to “snap, snap, snap,” led to her interest in sunrises.

When the weather is warm, Tjaden also likes to capture images of cardinals and warblers perched on the fountain in her yard, next to big, overflowing pots of impatiens. She calls it her “bird photo booth.”

Every morning, she takes between 15 and 20 photos, and then sorts them into folders on her laptop, deciding which ones to delete and which ones to keep.

“You look and you look and you look,” said Tjaden. “Which one is absolutely in focus. Which one is the best.”

By the time the sun is high in the sky, and Burlington begins to stir, Tjaden is already packing up her camera and heading inside.

Floodwall

Flood ravages Burlington and covers Gulfport, Illinois, across the bridge as record river levels fall after a levee break Tuesday June 17, 2008. | John Gaines | The Hawk Eye

Burlington aims to tame the Mississippi River with flood wall

BY TANNER COLE

At its headwaters near Lake Itasca, Minnesota, the Mississippi River is about three feet deep. By its end at Algier's Point, Louisiana, it's a 200-foot drop.

The water takes about three months to flow there, according to the National Park Service.

Once it arrives, the river expels its waters in one last show of strength. It expels 593,003 cubic feet of water into the Gulf of Mexico every second.

All that water, and all that force, has left a mark on Burlington. But the engineers and the construction crews building a wall on the city's riverfront believe their work can withhold it all.

In 2008, it left a mark on Bonnie Baldwin's shop that's still there today. She memorialized it with a line drawn on the wall.

"I will be very happy to see the flood wall completed," Baldwin said.

Baldwin owns the Iowa Store — a tiny souvenir shop in a corner of the Port of Burlington. She leases from the city.

She remembers all the floods, because each one filled her store with water before making it to other riverfront businesses.

Standing behind her cash register, Baldwin pulled out records of the last year's sales. Leafing through, she made some estimations of the money floods have cost her.

The flood of 1993 closed the store for June, July, August and September. She lost $6,000 to $7,000 in sales a month.

They didn't have much warning that year, so much of the merchandise was removed by boat. Carpet needed ripping up.

"I'll just be so happy not to have to vacate the store again," Baldwin said. "The physical part is just about as bad as the financial."

Baldwin's mark on the wall isn't the only one of its kind. A fire hydrant outside Frank Millard and Co. bares a yellow-labelled "2008 FLOOD 25.73 ft." The 2008 and 1993 floods are marked in a horror movie-esque font on a wall in Big Muddy's.

"Having done this for two years, I don't want to do it again," Baldwin said.

But while riverfront shops like Baldwin's stand to gain protection from the wall, moves to contain the water may have an impact elsewhere.

Burlington's flood stages themselves could very well change. The National Weather Service in the Quad Cities sets flood stages by contacting local officials. Different stages are based off what levels of local damage occur at a given river level, according to NWS Meteorologist Alex Gibbs.

For instance, the NWS lists water entering the Port of Burlington parking lot as a 17-foot river. A 18-foot river marks a moderate flood stage in Burlington. That's when waters "affect" the Memorial Auditorium parking lot and Bluff Harbor Marina.

One of the local officials the NWS polls is Des Moines County Emergency Management Coordinator Gina Hardin.

Hardin remembers 2008 like a vivid nightmare. The flood brought national aid and attention, and Hardin dealt with much of the logistics. She's ready for a wall.

"Basically, we're trying to save all that effort and time we spend on flood protection, but on a continual basis," Hardin said. "In the long run, it's going to save basically everyone money."

Hardin said local officials were "concerned about the levee system north of town breaching" when Gulfport's levee broke, taking tension off other areas and destroying the Illinois town.

Kirk Siegle, chairman of the Two Rivers Levee and Drainage District Board, said the group hasn't had much discussion about the impact of the Burlington flood wall on local levees.

"As far as Two Rivers is concerned, we're not aware of any hydrology effects it may have on the river," Siegle said.

Siegle said he wasn't aware of any hydrology studies conducted on the wall.

Donna Dubberke, a NWS warning coordination meteorologist, said any specifics on the hydrological effects of the wall would have to come from such a study.

After the wall is built, Dubberke said, the river forecast center will add it to its modeling program. One thing is for sure, according to Dubberke: the water that ordinarily would be flooding Burlington's riverfront will now be going somewhere else.

"When a wall or any kind of levee is put in place, it takes away from given water storage," Dubberke said. "So the wall will basically remove areas behind it as potential storage."

Similar projects usually put the excess water in agricultural areas, she said. The only way to know for sure where it'll wind up this time is a specific study.

The flood wall included a hydrology study as part of its approval process, according to the engineering firm handling the wall for Burlington, Veenstra and Kimm. Project engineer Leo Foley said they had to submit a "no-rise" certificate to the Iowa Department of Natural Resources as part of the process.

"The no-rise certificate shows that in a 100-year flood, the wall or levee won't make the river rise anywhere else," Foley said.

Infrastructure

A series of barges are directed through a lock August 29, 2006 at Lock and Dam 18 north of Burlington. | Jess Lippold | The Hawk Eye

River transportation infrastructure investment sought

BY ELIZABETH MEYER

U.S. Rep. Cheri Bustos has taken the fight for improvements in river infrastructure to the White House this year, urging the president's budget director to include millions of dollars toward the cause in the 2019 budget.

“Our nation's inland navigation system provides a key strategic advantage to our nation's agriculture and manufacturing sectors,” Bustos said in a November letter to Mick Mulvaney, director of the Office of Management and Budget. “Unfortunately, the reliability of these locks and dams — constructed in the 1930s — will continue to decrease.”

Bustos, a Democrat representing Illinois' 17th Congressional District, which includes six counties along the Mississippi River, was advocating $10 million be included in the budget for the Navigation and Ecosystem Restoration Program (NESP).

Another $10 million, the congresswoman said, should go toward the Army Corps of Engineers' 2018 Work Plan.

“Shippers have legitimate concerns about increases in planned and emergency lock outages due to the age and status of this infrastructure,” Bustos said. “With 60 percent of our nation's grain exports traveling on the UMRS (Upper Mississippi River System), we cannot afford to let this situation worsen.”

In the Senate, Chuck Grassley of Iowa and Dick Durbin of Illinois were among a bipartisan group of senators that wrote a letter Dec. 22 to Mulvaney "urging the Administration to include sufficient funding" in the 2019 budget for NESP.

"Further investment in NESP would strengthen infrastructure and navigation for the entire river and recognize the significance of the UMRS (Upper Mississippi River System) ecosystem to surrounding communities and wildlife," the senators wrote. "With the expansion of world food and energy needs, the Mississippi River is poised to be more important than ever."

Lock and Dam 19 in Keokuk is one of many aging structures along the Mississippi River that could use the attention of more government funds.

Opened in 1957, Lock 19 saw more than 27 million tons of product shipped through its gates in 2016.

The primary commodities shipped through the lock are food and farm products, accounting for more than 19 million tons. “Chemicals and related products” come in second at 4.5 million tons. Other materials include coal, manufactured goods and petroleum.

Keokuk's system is part of the Army Corps' Rock Island District, which manages five river basins in five states: Iowa, Illinois, Wisconsin, Minnesota and Missouri.

“The biggest problem that the Rock Island District faces is the degradation of the locks and aging infrastructure,” said Allen Marshall, chief of corporate communications for the Rock Island District. “That said, we've got some pretty amazing maintenance teams that have done outstanding work to keep these infrastructure operating with little to no maintenance closures.”

Before President Donald Trump took office, he made bold promises about rebuilding what he called the nation's “crumbling” infrastructure.

As part of his transition to the White House, Trump pledged to invest $550 million in building projects and create an infrastructure fund.

One year in to his administration, that promise has not been fulfilled.

Even though Democrats and Republicans claim infrastructure improvements are a bipartisan priority, Congress did not tackle the issue in 2017.

“I am working to ensure that we are addressing the transportation needs of rural America, not just major cities,” said U.S. Sen. Joni Ernst, R-Iowa. “Improving Iowa's river infrastructure — by maintaining and modernizing locks and dams, streamlining the permitting process for projects, and helping secure federal funding for flood mitigation efforts — is a priority of mine and is critical to Iowa's economy, especially the ag sector.

“As discussions continue over an infrastructure package,” she continued, “I look forward to advocating on behalf of Iowans and the needs of our state.”

Keokuk lock master Allan Dickerson has been the lead man at Lock and Dam 19 for three years.

The Carthage, Illinois, native said concrete issues have been the biggest repair headache on site. However, Keokuk has been more fortunate than some in getting its construction needs addressed.

In 2014, the lock was rehabbed to include new lower gates and the upper guard gate is set to be replaced this summer.

“And the service gate, they're looking at it in the design phase,” Dickerson said.

Dickerson, 62, said he had no immediate plans to retire and he liked his job, despite the financial and mental toll it can take.

“You're in charge of a $3 billion site,” he said. “Basically a lot of my stress comes from personnel issues. I've got to keep it staffed 24 hours a day, 365 days and year and trying to keep everyone can be difficult.

“We don't have enough people a lot of times.”

Identity

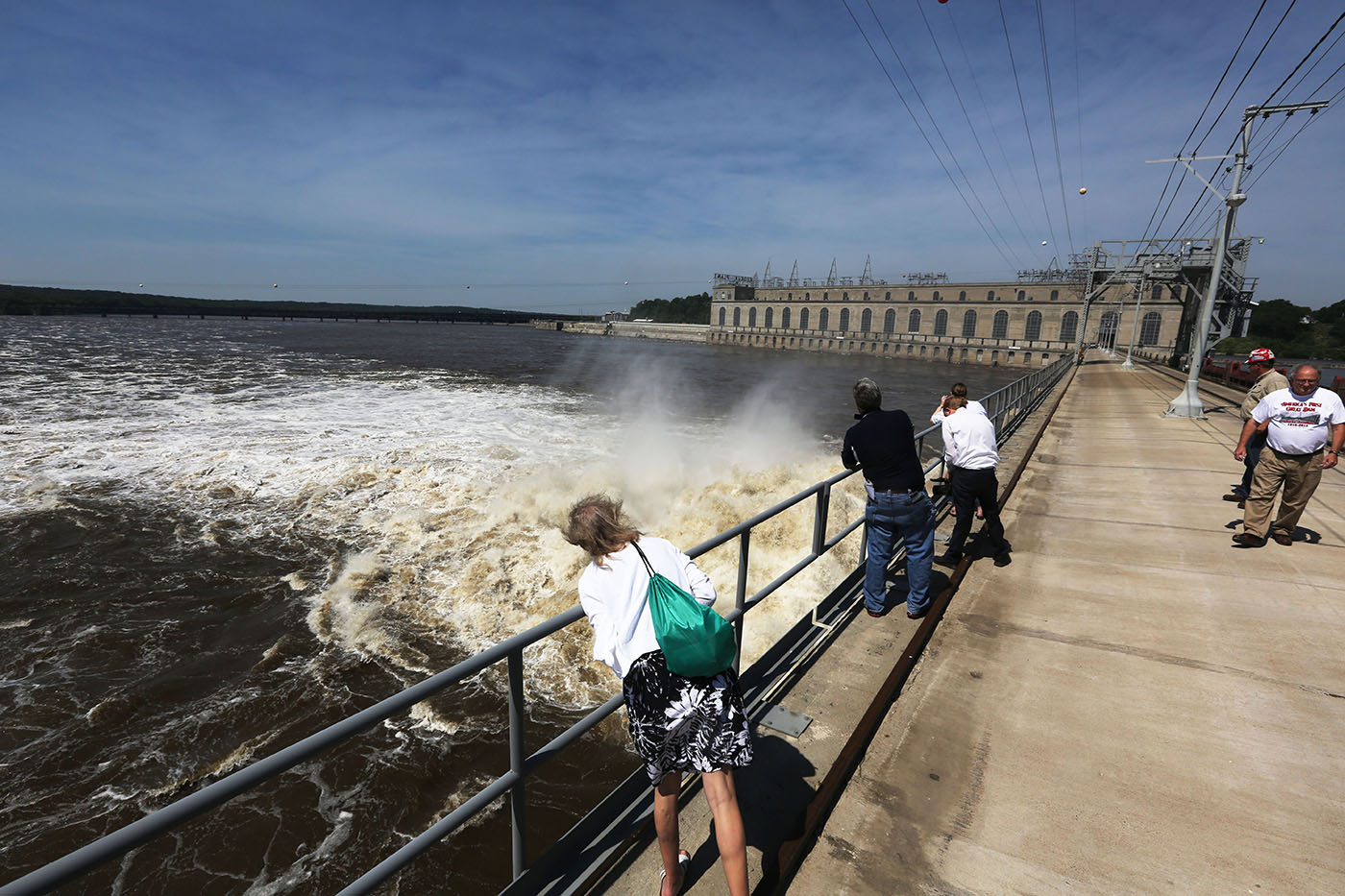

Visitors check out the Keokuk-Hamilton Dam during a media event for the 100 year celebration of the Dam and Powerhouse June 20, 2013 in Keokuk. | John Lovretta | The Hawk Eye

Towns find identity in Mississippi River

BY JULIA MERICLE

For most communities nestled along the Mississippi River, the waterfront location provides much more than a beautiful view.

A relationship to the river provides a strong sense of identity for many cities along its banks.

It offers a rich history, creates and sustains jobs and instills a source of pride.

Keokuk’s Energy Center and Dam

The Keokuk Energy Center and Dam, completed in 1913, turned the “Des Moines Rapids” into a source of power.

When constructed, the dam, which spans 7/8 of a mile wide, is 29 feet thick at the top, 42 feet thick at the base and 53 feet high, was the largest monolithic concrete dam in the world at the time of construction.

The Keokuk Energy Center and dam have put the Mississippi River town in the spotlight for many other “firsts” for hydroelectricity in the country. At the time it was built, the project marked the only commercial hydroelectric facility on the Mississippi River, the largest turbines, the heaviest rotating weight suspended on a single bearing and the first long-distance transmission line, to name a few.

“It was quite a feat because at the time they said this could not be done,” said Phil Tracy, a local historian. “That they could not build a dam where the rapids were. And Hugh L. Cooper, who was the chief engineer, proved them wrong.”

Today, the dam and energy center serves as one of three hydroelectric plants in the Ameren Missouri system, and the largest privately owned and operated dam on the Mississippi River.

The energy center has provided generations of local workers with employment, and still provides generations of people with electricity, especially from the St. Louis area near where the Ameren Missouri electric utility company is located.

In an effort to preserve Keokuk’s history, Tracy and a group of others are working to open a Hamilton Keokuk Dam Museum this Spring. He said plans for the museum include a historical timeline, photographs documenting the construction of the dam, and a virtual tour of the current energy center, which is not open to the public.

Fort Madison’s 'Old Fort'

While talking about Fort Madison, Andy Andrews of the North Lee County Historical Society called it, as many residents do, “where Iowa began.”

The old city began as the first permanent U.S. military fort on the Upper Mississippi, and the first legal settlement of white U.S. citizens in Iowa. Also the site of Native American leader Black Hawk’s first battle against U.S. troops, a plot of land off the river marks the only War of 1812 battlefield located in Iowa.

The fort was established to maintain control of land following the Louisiana Purchase and to trade with Native Americans in the river region. However, the historic land has created a lasting impact on the residents of Fort Madison for decades.

Any day now, Andrews hopes the battlefield site, located at an empty plot of ground across the street from the “Old Fort” and next to the Dollar General, will be added to the National Register of Historic Places.

When added, Andrews said, he and the North Lee County Historical Society can proceed with obtaining the War of 1812 tombstones for the 22 soldiers who died fighting there between 1808 and 1813.

Plans are in place to turn the site into a memorial park. Andrews said about $79,000 out of a goal of $500,000 have been raised to date, but the opportunity to apply for grants might become available soon.

“Hopefully when it gets put on the National Historic Register we can get more funding through other sources,” Andrews said. “Of course, it lies right next to the original site of the Old Fort Madison, which is already on the National Historic Register.”

Nauvoo’s Mormon Exodus

The Mississippi River does not currently provide much commercial or economic impact in Nauvoo, according to Susan Sims of Cedar Rapids. Rather, it serves a nostalgic and sentimental purpose.

Sims is currently assigned to manage public affairs for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Iowa and western Illinois.

The little peninsula jutting out into the river, which was once a mostly undeveloped town called Commerce, became the prosperous city of Nauvoo with the arrival of Joseph Smith and the Mormons.

The Mormon religion originated in Palmyra, New York, and after being chased out of a couple other towns because of their religious beliefs, the first Mormon prophet Smith deemed Nauvoo the headquarters of the religion.

The Mormon people built a thriving community along the river from 1839 to 1846. They arrived in Nauvoo with 5,000 members and by the time they left nearly 18,000 members from around the world had come to settle in the city. At its peak, the population of Nauvoo rivaled that of 1840s Chicago.

After Smith’s murder in 1845 and mob brutality toward the Mormons in Nauvoo, the second prophet Brigham Young led an exodus westward across the river to the current Mormon headquarters in Salt Lake City, Utah.

The Mormon community built a massive temple overlooking the river during their stay in Nauvoo, but arsonists burned the structure in 1848.

It was the economic opportunities of the river that helped Mormons settle in Nauvoo, but also the river that played a role in their leaving. Sims said right about the time the Mormon exodus began in February of 1846, the Mississippi River froze solid for a short time, allowing horses pulling wagons full of people to traverse the ice without the use of boats.

Many ferries were used in the exodus once the ice melted, but that first freeze allowed a large number to flee.

This was the beginning of the Mormon Pioneer Trail, and families walked hundreds of miles through the harsh winter weather to seek a new home for their religious community. The Mormon people had planned to wait until spring to head west, but rumors of government intervention and increasing hostility drove them out early. Due to the rushed departure, Mormons left behind many essential provisions, making the trek to Salt Lake City even more difficult.

Today, visitors come to see the rebuilt Nauvoo Temple and other historic sites from 1839 to 1846, driving the city of Nauvoo’s current economy. The 54,000-square-foot temple sits on the original 3.3 acre temple block, and reaches up 162 feet and 5 inches high. The structure is a nearly exact duplicate of the original Mormon temple from the 1840s, and can be seen for miles up and down the Mississippi River.

Boating

Sheriffs deputies and Department of Natural Resources officers return from a Mississippi River search May 25, 2015 at Lock and Dam 18. Two men went over the rollers of the dam late last night. | Josh Newell | The Hawk Eye

Respect key to boating safety

BY ANDY HOFFMAN

Many self-proclaimed "river rats" say the two most important things to remember while boating on the Mississippi River is to respect each other and, more importantly, respect the river.

Des Moines County Sheriff Mike Johnstone, himself a lifelong river rat, couldn't agree more.

"My dad always told me to treat the river with respect because it can take your life in a second," Johnstone said recently, as he reflected on the many decades he has spent on the Mississippi River. "I have always remembered that. If there is one thing my dad taught me about the Mississippi it's to respect it.

"I’ve seen that river in all its beauty and I’ve seen it in all its fury. The river is a wonderful thing to live next to. I love going out there every chance I get. But you have to respect it. It is constantly changing, not only by the day, but by the hour and minute. It is a moving, living, breathing thing."

Johnstone's comments were echoed by other law enforcement officers charged with enforcing rules and regulations on the Mississippi River, including Paul Kay, the Iowa Department of Natural Resources conservation officer for this area.

“Rivers are more dangerous than lakes because of the current,” he said. “If you have an engine failure on the river, you are at the mercy of the current. Floating objects also present a hazard, especially during high water.

"Just remember to know the river and know your own limitations. And always have an awareness for the other boaters around you."

Public safety groups take on different roles policing the river. While most agree DNR has the greatest exposure to boaters on the river, police and sheriff's departments, along with area fire departments, have unique duties.

In most instances, DNR and law enforcement agencies leave the water rescues to area fire departments, who have training in all types of water emergencies, including rescue and recovery operations.

According to Alex Murphy, a public information officer with DNR, through September of 2017 there had been four fatalities and 19 injuries related to boating accidents on rivers and lakes in Iowa. In 2016, there were six fatalities and 18 personal injuries in the state.

In the past five years, seven people have died in boating accidents in the area, including four Burlington youths killed on Memorial Day weekend in 2012 when two jon boats collided as they shuttled partygoers to and from an island north of Burlington; one man died on Memorial Day weekend in 2015 near Lock and Dam 18 when his small fishing boat overturned; and two commercial fishermen died in February near Montrose when their boat capsized in treacherous conditions.

In most instances, friends of the victims would tell you they were experienced, confident boaters.

"You have to understand the river is wild, it will take you in a heart beat if you are not careful and it won’t give you back," Johnstone said. "You simply just can't take it for granted. You always have to be aware of your own limitations, because the Mississippi River has no limitations."

During recent discussions with several law enforcement officers and emergency rescue teams, it became apparent there are many aspects of policing the Mississippi River that require joint efforts from agencies across the spectrum.

"We work very closely together," said Burlington Fire Chief Matt Trexel of the various state and local agencies that share responsibilities for handling a wide range of incidents on the river. "We share a boat with the Burlington Police Department. And we work closely with other agencies up and down the river. All the fire departments along the river have their own boats. We also have utilized dive teams from nearby cities in Iowa and Illinois when needed."

Kay also stressed the need to know the rules and regulations involving boating activities. He said DNR officers are on the Mississippi River on a regular basis, enforcing laws to ensure public safety.

While it doesn't occur as often in the winter as it does in the summer, alcohol intoxication is a year-around concern for officers on the river, he said.

“The alcohol limit for operation of a boat is 0.08, the same as driving a vehicle on a roadway,” he said. “It is not against the law to have an open container of alcohol in the boat, but the operator must be below 0.08 while operating the vessel.”

He also stressed “boats operating at speeds over 5 mph, must maintain a distance of 50 feet from each other. If a vessel is going faster than 5 mph and comes upon a vessel operating slower than 5 mph or is anchored, it must maintain a distance of 100 feet or greater.”

Another way to avoid being ticketed is to make sure you have your vessel properly registered. He said vessel registration lasts for three years.

Kay said in addition to the specific requirements, the DNR recommends boats include “ropes, oars, replacement bulbs for lights, a flashlight or spotlight and a cellphone or marine radio.”

Johnstone also recommended boaters carry an anchor on the boat.

"It's not required by law, but it sure can come in handy if your boat loses power or has other problems that would allow it to drift aimlessly with the current," he said. "It's hard for people to imagine how swift the current can be and how fast it will take you downriver towards the (Keokuk) dam."

While the duties of DNR and local law enforcement often overlap, Johnstone said the two entities have different roles on the river.

"DNR is very particular about rules and regulations," he said. "We will make stops of boats on the river to make sure they have the needed equipment — life jackets and that kind of stuff. They are looking for people violating boating rules, registrations and boating while intoxicated.

"We do some of that, but that is not our emphasis when we are in the river. We are just not going to pull people over. They have to be doing something that caught our attention that could be illegal. We don’t do what the DNR does — we rarely stop people to do safety inspections."

Johnstone likes to instruct his deputies, all of which can operate the department's boat, to approach their time on the river the same as if they were in their squad cars driving down a highway.

"We try to police boaters on the river the same way we patrol our roads and highways," he said. "If we see someone and it looks like they could be violating the law, we will stop and check them out. For example, we look for people operating their vessels recklessly or are possibly violating speed and distance regulations. If we see somebody operating a boat while intoxicated, we will arrest them."

For Johnstone, having members of his department train on the water is imperative.

Trexel agreed.

"It is very important as a department that we be trained for incidents on the river," he said. "It’s right next door to us. We can do ice and cold water rescues, but we don't do swift water rescues ... We call other agencies for assistance.

"We have a boat we share with the police department," he said. "The police department often uses the boat for patrolling the river during high-traffic times like Steamboat Days. We use it for rescues. We don’t do any patrolling."

Lee County Sheriff Stacy Weber said his department spends most of its time on the water assisting local agencies during a river incident.

"Right now we are in a difficult spot because we don't have our own boat," he said. "And that's a problem because if you look at ...... It could be better. A lot of times we find ourselves just walking the short lines. So, right now, we are proactively looking for grants to allow us to purchase a boat.

"We rely on the DNR to enforce rules on the river, such as operating while intoxicated. We would like to be able to police the river with our own boat, but that’s not possible right now.

Weber said it's frustrating for the sheriff's department not to have its own boat, especially since most of Lee County is surrounded by water.

"We would like to be able to assist the DNR in patrolling all the rivers that surround Lee County, not just the Mississippi," he said. "I don't know if you realize it, but Lee County is almost completely surrounded by water with the exception of a small portion in the northern part of the county near Henry County.

"Everywhere we go in Lee County we are around water. With the Mississippi, the Skunk, the Des Moines River … We are always doing something around or near water … It would be great to have a boat. I think it would be great to be able to assist our citizens who spend a lot of time on the river."

Like most others law enforcement officers who spend time in and around the river, Weber wanted to emphasize safety and respect for those taking to the water"

"It's just common sense, that's all it is," he said. "Use good judgment, follow the rules and respect the Mississippi and those around you and there won't be any problems.

Johnstone had one last tip for boaters:

"Have a float plan," he said. "Tell people where you are going and when you will be back. Take a phone with you. Have a designated boat operator. Have your flotation devices on you or nearby. And then you can relax and enjoy the wonderful experience of being on the Mississippi."

Fish

Jim Kent of Fort Madison clips a fishing hook out of a bass fish he caught Nov. 27, 2016 at the Bluff Harbor Marina on the Mississippi River in Burlington. | Erin Lefevre | The Hawk Eye

River fish offer excitement, trouble, food

BY MICHAELE NIEHAUS

If you’ve lived near the Mississippi River for very long, chances are you’ve heard the tale of a catfish that lurks along the murky river bottom, its eyes the size of Volkswagen headlights and its mouth big enough to swallow a man whole.

Having grown up in Burlington, Chris West, who now lives in Stronghurst, Illinois, knew the old wives' tale well when he started what would become a 12-year diving career with Davenport-based GOE Underwater and Marine Service. He never did see such a fish, but he did have a close encounter that may be similar to one that helped inspire the myth of the man-eating catfish.

About eight years ago, West was diving in Fort Madison searching for the Fort Madison and Niota, Illinois, water intake. It was the first time the company had done work on that particular pipe. The current was strong and the Mississippi was as muddy as ever.

Struggling to maneuver through the current, West grabbed onto what he thought was a severely clogged pipe. He reached under what turned out to be a tree and scratched the bottom, hoping to expose metal, which would indicate he had found the intake. But it wasn’t metal he was scratching.

“It was the inside of a catfish’s mouth,” West said. “He clamped down on my upper arm and started sucking my arm in, so I ripped my arm out and jumped underwater — which is pretty hard to do — screamed like a little girl, and went hand over fist on my tether umbilical rig trying to get myself out of the water.”

It was on his way back along the tether that he ran headfirst into the intake he was looking for, and fish encounter be damned, he stayed there to finish the job. The fish remained under the tree.

“The fish took about 2 foot of my arm in its mouth, so it had to have been pretty big. I wasn’t able or willing to stick around and see how big he was. I was out of there when he clamped down on my arm,” he said.

The myth of the man-eating catfish likely began in the 1670s, when Native Americans warned French explorers Jacques Marquette and Louis Joliet of demons and giant fish living in the waters ahead of their voyage down the Mississippi from the mouth of the Wisconsin River. Marquette wrote of their canoe colliding with the river monsters on more than one occasion.

Mark Twain gave credence to Marquette's claims in "Life on the Mississippi," in which he wrote of a six-foot-long, 250-pound catfish.

No such fish has been caught from the river, but Tim Pruitt's 2005 catch of a record-holding 124-pound blue catfish near Alton, Illinois, came close.

The Mississippi is home to 10 species of catfish that fall into three categories: blue, flathead and channel catfish.

"Catfish are just a good, adaptable fish. They can take muddy conditions," said Andy Fowler, a fish biologist with the Iowa Department of Natural Resources. "They're made for rivers. It's kind of their ideal habitat."

The river provides an ample food source, varied habitat and the cavities of which they are so fond and rely upon for spawning, which begins in spring and goes until May or June. About four to six days after eggs are laid, they hatch.

Flathead and blue catfish often live longer than 20 years. Blue catfish grow larger and more quickly than flatheads.

According to Fowler, a couple 40-pound flathead catfish the DNR identified not long ago were estimated to be 25 years old. The previous record-holding blue catfish, caught by Greg Bernal of Florrisant, Missouri, in 2010, was about 18 years old and weighed 130 pounds.

Blue catfish prefer warmer waters and tend not to travel further upstream than Missouri. The migratory fish used to be abundant in Keokuk in the summer months, but their numbers have declined with the construction of dams. Fowler said a couple have been seen just below Keokuk.

Flathead and channel cats don't mind the cold and flourish in the waters of southeast Iowa. Channel cats can live longer than 15 years and average about 2 to 7 pounds, though the record channel cat weighed 58 pounds.

Paddlefish

Another river giant is the American paddlefish, easily distinguishable from other fish by its long gill covers, shark-like mouth and elongated snout. According to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, this species, also known as the spoonbilled catfish and a cousin of the sturgeon, has been around for at least 400 million years.

Despite this, the exact function of the paddlefish's long snout remains unknown, though the sensory system the snout contains suggests it is used to detect food. Another theory is that it's used to stir up food from the river bottom. It also has been suggested it serves as a kind of rudder to guide the fish.

It's numbers have dwindled in recent decades due to over-harvesting — they are said to be quite tasty, as is the caviar they produce — and destruction of habitat. Dams interrupt natural spawning migration, for which they require access to areas with sand or gravel bars.

Paddlefish fishing was banned in the Missouri and Big Sioux rivers for 29 years due to concerns about their declining population before the DNR reopened paddlefish fishing season in 2015, so long as anglers obtained a paddlefish license and an unused transportation tag.

Such regulations were not put in place for paddlefish fishing on the Mississippi, of which they now occupy only certain parts where water is slow-moving and deep, such as Pool 19 in Lee County and slightly down river from wing dams. They also have been found in the Skunk River. Most are caught in spring below dams.

"They're an open-water species," Fowler said.

These fish, which can weigh more than 100 pounds, can only be caught by snagging. With this fishing technique, a fishing line is pulled quickly out of the water as soon as any movement is felt on the line, with the intention of piercing the fish in the flesh with the hook.

Anglers need no bait to catch these fish.

That's because paddlefish are filter feeders that eat only on zooplankton, a microscopic creature in increasingly high demand by the Mississippi's inhabitants.

"(Paddlefish are) one of those species that we worry about when we have Asian carp," Fowler said.

Unwelcome residents

Bighead carp, one of three Asian carp species that eat zooplankton, have been found to school with paddlefish, according to netting studies in the Mississippi River conducted by the Illinois DNR, and may compete with them for food.

The invasive Asian carp have been in Mississippi waters since the 1980s. First brought to U.S. fish farms in the 1960s and '70s, the four carp species — bighead, silver, black and grass — were never meant to make it into natural bodies of water, but they eventually did due to flooding.

Since then, the carp have been making their way upriver in the Mississippi, as well as the many rivers that flow into it.

Fowler said because three of the four prolific species feed on zooplankton, the base of the aquatic food chain, they're a threat to other fish species all the way up the line. They also make for serious competition for other filter feeders.

"It seems like the Asian carp are more adept at reproducing than paddlefish," Fowler said.

Asian carp lay up to 300,000 eggs per clutch, though the bighead carp can lay up to 750,000. They're also hardy fish that adapt well to varying environments.

They are thought to lower water quality and are known to push other fish out of their environments, both because of the physical space they take up and because of the strain on resources they cause.

Silver carp also are a hazard to boaters. The fish, which can weigh more than 60 pounds, respond to boat motor vibrations by jumping as high as 10 feet out of the water. Getting hit with a fish that size can cause serious injury.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the National Wildlife Federation and DNR have been trying to come up with ways to combat the spread of the invasive species before they make their way into the Great Lakes, but it's proving to be difficult.

"It's a hard political issue. You can't really shut down the river," Fowler said.

Instead, the agencies are trying electric, acoustic and bubble barriers aimed at assaulting the carps' senses in the hopes they turn around before entering more waterways. The corps also is testing a carbon dioxide barrier at Lock and Dam 14 in the Quad Cities, but the barrier's effects on water quality must be considered before its ability to repel fish can be examined.

The Corps also has adjusted the gate at Lock and Dam 8 near Genoa, Wisconsin, and before last year, DNR officials were hopeful Lock and Dam 19 in Keokuk would be able to keep the fish at bay.

"It's one of our highest drops in the river, and so it really was a good barrier," Fowler said. "Last year is when we first saw them getting by Lock and Dam 19."

Another proposed way to combat the carp is by stocking the waters in which they live with predators, such as alligator gar, but that also would have drawbacks.

The DNR has begun radio tagging Asian carp so they can be tracked. It is hoped that this will allow the state agencies to determine range and feeding locations, as well as other behaviors. That information could allow the DNR to target specific areas at certain times of the year to target the fish, but Fowler said there so far hasn't been an evident pattern.

On the plus side, carp make for good eating, if you don't mind dealing with the spine. They're high in protein and— because they don't eat other fish — low in mercury. They also lack a "fishy" taste, allowing the meat to easily absorb the flavor of sauces, spices and herbs.

Like the paddlefish, Asian carp must be snagged.

Birds

An American Bald Eagle flies by the Great River Bridge Feb. 17, 2016 on the Mississippi River near the Port of Burlington. | John Lovretta | The Hawk Eye

Port Louisa a Mississippi Flyway rest stop

BY MICHAELE NIEHAUS

While the many dams and levies along the Mighty Mississippi protect infrastructure and people living along its banks from flooding, they’re not conducive to the natural habitats relied upon by the hundreds of bird species that take to the Mississippi River Flyway during migration.

That’s why Port Louisa National Wildlife Refuge was established in 1958 to protect migratory birds that travel along the major flyway, its four divisions — Louisa, Keithsburg, Illinois, Big Timber and the Iowa River Corridor — spanning 18,373 acres. Port Louisa is part of the National Wildlife Refuge System network, which began with the establishment of Florida’s Pelican Island in 1903.

During the long and arduous journey each spring and fall, a plethora of songbirds, raptors and waterfowl land at the refuge for rest and food before taking off again en route to their summer or winter homes.

"One of our main purposes is to provide that sanctuary and refuge habitat," said Port Louisa biologist Jessica Bolser. "So for migrating water birds, to minimize disturbance to those birds, we’ll close certain portions of the refuge to public access."

The Louisa and Keithsburg divisions are closed from Sept. 15 to Jan. 1, and the Horseshoe Bend Division is closed from Sept. 1 to Dec. 1.

Hunting is not allowed in the refuge, but it is at nearby Lake Odessa. Migration requires much effort and energy expulsion from the birds, so it's important they have safe, quite places to rest along the way.

In December, waterfowl stopped in the Louisa Division wetlands in droves, the honks of geese giving way to the distinct calls a group of trumpeter swans coming from a nearby pool.

Trumpeter swans are making a comeback in Iowa, a state in which they used to nest and flourish. Human settlements and agriculture gradually took over and drained the wetland habitats in which they lived, and their population quickly dwindled.

From 1883 to 1998, Iowa had not a single pair of wild nesting swans. The Iowa Department of Natural Resources started the Trumpeter Swan Restoration Project in 1993, and their numbers in the state since have slowly and steadily improved.

As the swans trumpeted and dove beneath the water's surface in search of food, more than half-a-dozen bald eagles circled overhead. Another perched in a nearby tree, where it either was preparing or protecting a nest. Eagle populations along the Mississippi River, where thousands of eagles spend the winter, begin to grow in September and reach their peak in January.

“We’re starting to see more activity around those nests,” Bolser said.

She and others who work on the refuge note bird behaviors while doing fieldwork. Aside from conducting surveys to provide a rough estimate, the refuge does not monitor the birds.

Like many bird species, eagles mate for life and, unlike other raptors, tend to return to the same nest each year, adding onto it ahead of each clutch of eggs. Some will stay there year-round, and others will fly north during the summer months.

"There’s adult eagles on that nest again this year," Bolser said of another nest in the area. "So they’re trying it again. Last year, their eggs didn’t hatch."

In the spring, as some eagles leave the refuge in search of cooler temperatures, songbirds and waterfowl will make their way back into the area from South and Central America.

Songbirds like the Dickcissel will flock to grasslands and meadows, where they'll build nests near the ground in small shrubs or dense grasses.

Other bird species, like the prothonotary warbler and wood duck, will seek out flooded bottomland forests and wooded swamps, habitats that are ideal for cavity dwellers.

"While many warbler species are migrating through and moving north, some (prothonotary warblers) will utilize this habitat we have here on the refuge," Bolser said.

The prothonotary warbler is the only warbler species to nest in tree cavities.

Among her favorite bird species that frequent the refuge, Bolser said, the prothonotary warbler's bright yellow plumage and song are seen and heard most in the late spring and early summer.

"The warblers are not very shy," Bolser said. "They’re just singing and kind of flying around."

Because the feathered visitors' food and habitat needs vary so much by species, those who manage the refuge do all they can to ensure variety is readily available.

“We try to provide a lot of variety of different wetland types, a lot of depths,” Bolser said.

The refuge uses levies to create these varied depths.

Port Louisa's land lies within the historic floodplains of the Mississippi and Iowa rivers. Most of that land now is behind levies built by the Army Corps of Engineers.

"What used to be a very natural river system is no longer, so what we try to do is mimic what naturally would occur within those floodplains," said Sally Flatland, who manages the Port Louisa refuge.

The refuge is able to manage some divisions more heavily than others. Part of the levy system in the Horseshoe Bend Division — which is on the lower part of the Iowa river slightly north of where it flows into the Mississippi — is breached, so the refuge is observing the area as water levels fluctuate naturally. Flatland hopes doing so will give the refuge and DNR insight as to how to better plan future water control structures.

In the Louisa Division, the refuge lets spring flooding run its course. As the waters begin to recede in the summer, it uses pumps to draw down water further, where needed, to expose mudflats and soil. This allows for vegetation stimulation.

"If it's all under water, you're not going to get that vegetation response," Flatland said.

Among the desired species of vegetation are sedges and smartweed, typical wetland plants that thrive in moist soil and produce large amounts of seed for migratory waterfowl and other wildlife. The plants also attract insects, another food source for migrating birds.

"Variety is very important, because each plant, depending on the timing of growth — not everything comes up at once — so you can spread variety or species of plants throughout longer periods of the season it provides a longer period for food and also a diversity of different levels of protein produced by the different plants," Flatland said.

Once stimulation has occurred and plants begin to grow, water is drawn back into the area. Flooding the area helps the vegetation to grow and spread, making for an attractive rest stop for birds along their migratory route.

River Rats

Ginny Ritchey cast her fishing pole fishing along the Mississippi River with her friend Emma Ferguson June 30, 2017 behind Memorial Auditorium. The two women decided to try their luck fishing while their husbands played golf. | John Lovretta | The Hawk Eye

River rats not extinct on the Mississippi

BY BOB SAAR

You don't have to integrate with river rats, at least not on their level — which is water level. What, exactly, is a river rat?

Merriam-Webster says this: "One who spends his leisure time on or along a river."

Around here, that would include the lowly muskrat or a stray dog roaming Tama Road, but we're talking about the human variety.

A river rat knows America was built along her great waterways — the Hudson, the Ohio, the Mississippi, the Columbia and the mighty Missouri.

John Archer is a born and bred river rat. He began going out on the Mississippi when he was 3 with his father, Jack. He's run Archer Auto Marine in Burlington since 1989.

"A river rat?" Archer wondered. "It's somebody born and raised on the river. Somebody who's obsessed with the river. Is best friends with the river. They respect it highly, and know it can be dangerous. They take care of it, the beaches, the nature — all of that; they respect it and look after it."

He said 'rats help police the river.

"The people who dump beer cans on the beach? A river rat doesn't do that," he said.

Local river rats are folks who venture forth on the Mississippi for economic purposes as well as for entertainment.

Commercial fishers spend day after day on the water, seeking catfish, carp and buffalo, a carp-like species of rough fish. They fish year 'round, risking their lives on the winter ice when an open hole is the only piscary. Some of them die doing their job.

Smoked carp is a delicacy on our river, but people on the west coast turn their noses up, preferring salmon and other seagoing royalty to our lowly bottomfeeders.

River rats don't worry about that. Smoked roughfish goes great with cold beer on a hot summer's day.

Ryan McSparen of Stronghurst, Illinois, started 'ratting with his fisherman father.

"I grew up on my dad's plate boat that he still, to this day, commercial fishes with," McSparen said. "He's been fishing the river for 50 years with one."

A plate boat is a big, heavy flatbottomed rig constructed of heavy-gauge, high-tensile aluminum alloy, or "plate," with a sub-floor frame under welded-in aluminum. It doesn't go "wham-bang!" when you slam it over a barge's wake.

The coal barges that ply the Father of Waters, running from the Twin Cities to Memphis and on down to Baton Rouge, are populated with roughnecks who scurry across the decks, keeping things shipshape as their captains raise or lower their vessels through the Upper Mississippi lock-and-dam barriers from Upper St. Anthony Falls in Minneapolis, Minnesota, to Chain of Rocks in Granite City, Illinois.

A river rat is someone who knows it's far easier to dock a boat in the mysterious gravitational currents of the Mississippi than in the placid, lifeless lapping of a still body like Lake Geode.

Following World War II, from the 1950s into the early 1990s, pleasure craft swarmed our pool, Pool 19 below Lock and Dam 18 — technically, it's above Lock and Dam 19 in Keokuk, but the dam just upriver from Burlington is "ours."

Pool 19 is 46.3 miles and 30,466 acres of aquatic habitat. The lower portion is mostly wide-open water, but the upper half is a mini-wilderness of islands, sloughs, and backwaters corralled by levies, which have degraded much of the off-channel habitats. The Iowa DNR’s Blackhawk Bottoms Wildlife Management Area is located in the floodplain of Pool 19.

A river rat can navigate all of Pool 19 without charts.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers used to dredge up plenty of clean sand beaches for the families that swarmed like, well, rats, filling those man-made meccas — incorrectly called sandbars, which are caused by river currents — with little kids, picnic baskets, charcoal fires and sand-encrusted hot dogs. Waterskiing thrived, and on big days — Memorial Day, the Fourth of July and Labor Day — it paid to have a lookout in the boat to help driver and skier alike negotiate the hordes of people on ski pairs, slaloms, innertubes and surfboards dragged behind fiberglass runabouts, jon boats, and anything else that could roar up and down the river powered by an outboard motor.

A river rat is someone who's been piloting the Mississippi in a boat of some kind since he was 12 years old.

McSparen is an administrator for the Pool 19 River Rats, a Facebook group that shares knowledge of events and happenings occurring on or around Pool 19.

It's also where inexperienced boaters can learn river safety and etiquette from veteran boaters.

Where wet-behind-the-ears pups can grow up to be river rats.

"A river rat, to me and my river family, is a group of people who pretty much consider ourselves family who hang out, do things, spend the holidays together throughout the year, even when the river season isn't available and the river's froze up," McSparen said, echoing Archer. "People who love and enjoy the river with everything they can, spending time with Mother Nature down to the conservation part of it, keeping the places picked up and tended to, respecting the river."

During the family picnicking heyday, waterskiing was the summertime replacement for football and basketball games, but not all river kids liked hanging onto the towbar for dear life.

"My parents owned a cabin up by the dam," musician David Schwarm of Burlington said. "My dad was an avid walleye fisherman, so I did a lot of that when I was younger."

Schwarm and his father would fish up by the Dam 18, right by the rollers with other walleye addicts, but he liked hanging out with his friends, too.

"I wasn't that good at waterskiing, so I decided tubing was more my style. We'd tube up and down the straightaway. I was a river rat in my younger days, middle school and before," he said. "Then I discovered Van Halen and I didn't want to go on the river anymore."

You can see by now that a river rat is someone who grows up going out on the river with dad.

The Great Flood of 1993 changed everything on the Upper Mississippi: Pelicans returned to their traditional summer backwaters and the Corps of Engineers lost its enthusiasm for dredging beaches.

All except the mighty ISU Beach south of Burlington.

The Iowa Department of Natural Resources maintains the deepwater beach near the Iowa Southern Utilities plant off Sullivan Slough Road south of Burlington. It can accommodate up to 100 boats of all kinds, regardless of river level.

You can hang out with ISU Beach fans online at Facebook, under "ISU Beach."

A popular low-water sandbar is Jon Boat Beach on Baby Rush island, between O'Connell and Otter islands upriver from Burlington, in the sloughs east of the Tama area.

"When the river's down below 9, 10 feet, you can get a hundred boats on Jon Boat Beach," McSparen said. "Everybody knows it's really only accessible to smaller boats, like jon boats, when the water is at deathly low levels." Draft on a jon boat is typically 10 to 12 inches. "Most speedboats, you're going to want to be running in at least 3 or 4 feet of water."

The beach near Dallas City, Illinois, is popular with Fort Madison boaters.

"It's straight across and maybe a hundred yards south of Ike's Riverfront Tavern," McSparen said. "You've got to cut across the channel diagonally just north of Dallas City. A lot of the big boats will cut around the south end of that beach because it drops off 50, 60 feet. On the west side of that island, if the water level's down low, you can walk out for a hundred yards from the beach."

Besides jon boats and speedboats, many Pool 19 'rats have pontoon boats, which are basically a flat platform with a sun shield, sitting atop a couple of long, aluminum float tubes. Pontoons are the easygoing, no-hurry element of summertime river fun.

"With a jon boat, you're getting a shower of water, speedboats can go really fast, and pontoons, you can pile a lot of people on it, plus equipment, tents and firewood," McSparen said with a laugh.

The alternative to those types of pleasure craft? Houseboats and cabins, river-based homes for many people with their own history and living nuances.

Besides, a river rat is someone who has to actually be out on the water, racing up and down Pool 19.

You can see all the varieties of boats during Burlington Steamboat Days, when they raft up off the Port of Burlington seawall to listen — sort of — to the music coming off the main stage.

A river rat knows that Steamboat Days is a great time to kick back without getting sand in your shoes.

"I believe they are people who want to use their boat and enjoy the music," former BSD vice president of entertainment Mac Coffin Jr. said. "I think most have tickets and come sometime during the week."

Steamboat Days has long guarded the visual portion of their musical menu by positioning a line of food kiosks along the seawall in order to block the view from the water.

"The only way they hinder BSD is if they never buy a ticket or spend any money. I think that might be a small percentage," Coffin said.

Part of the 'Boatin' boating fun is sending a skiff to shore to stock up on corndogs and other carnival treats.

But what does it mean to own a boat, anyway? Ask the local river rats and they'll tell you this: "Break out another thousand."

True: A boat is also a hole in the water you pour money into, and the two happiest days in a boat owner's life are they day they buy it and the day they sell it.

The bottom line is this: Whether someone spends a lot of time — and money — on the Mississippi River, for a living or just living it up, a river rat is a waterman for life.

The gender-neutral, politically correct term "waterperson" just doesn't have the right feel here, which is why those men and women are all properly called river rats.