The cautionary tale of Mill Cove

How a crown jewel of the St. Johns River vanished after engineers redrew its course

By Christopher Hong & Nate Monroe

As the ugly warts of industry, like paper mills and shipyards, spread along Jacksonville’s riverfront during the first half of the 20th century, old Florida was alive and well in Mill Cove.

Back then, one of the St. Johns River’s main channels flowed through Mill Cove, a six-mile body of water that runs beneath the Dames Point bridge along the north shores of Arlington.

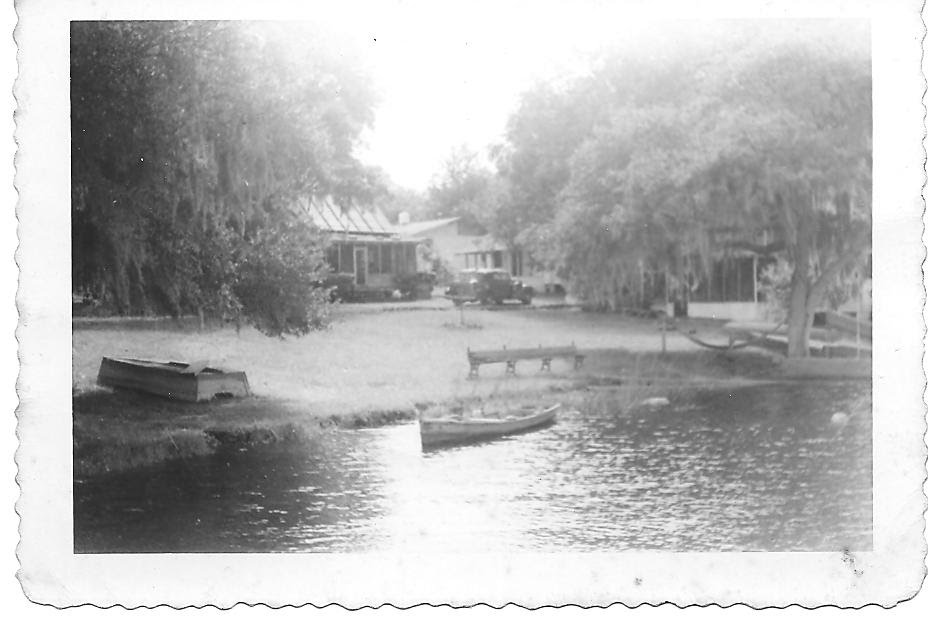

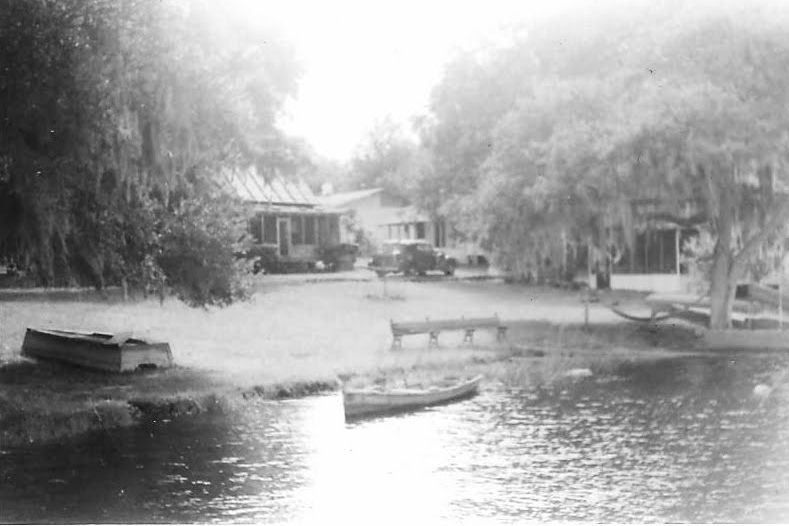

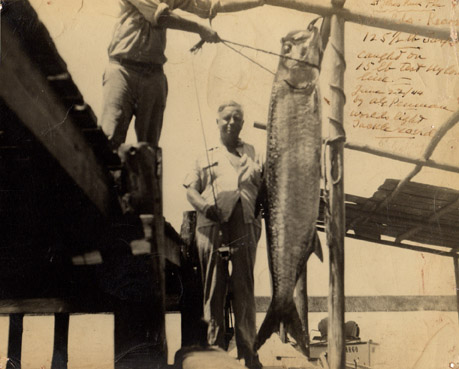

The river’s swift, clear waters carved a maze of sandbars and deep channels through Mill Cove that were surrounded by white sand beaches, a unique habitat that made for a fisherman's paradise.

Generations of commercial watermen supported families by pulling nets through the cove’s fertile waters for mullet, shad and shrimp. Mill Cove was also considered to be one of the best places in the world to catch tarpon, a hard-fighting game fish that grows as big as people.

Some locals even swear that Ernest Hemingway made a stop in Jacksonville to chase the silver kings of Mill Cove.

But the glory days of Mill Cove ended after the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers redrew the course of the river in the 1950s, triggering a series of unintended consequences that would permanently cripple the cove.

Today, Mill Cove is a stagnant, muddy backwater of the river. At low tide, most of the cove becomes too shallow for boats to venture outside of a man-made channel. Even kayakers can be left high and dry.

In many places, marsh grass and thick mud have replaced water. Homeowners long ago had to extend their docks over the new patches of marsh to access the water, which has receded further away from back yards and in some places, completely disappears during lower tides.

Residents once filled town hall meetings demanding the government restore their hallowed fishing and boating grounds, but the public outrage over Mill Cove’s demise fell silent decades ago.

Still, environmentalists say Mill Cove's cautionary tale is as relevant as ever now that the Army Corps and city officials are moving forward with another major change to the river: deepening its shipping channel from 40 to 47 feet.

St. Johns Riverkeeper Lisa Rinaman, a leading voice among opponents to the deepening project, said the Army Corps has downplayed or failed to examine the environmental impacts of the project, like salinity intrusion upriver and an increased risk of storm surge flooding in urban areas.

Rinaman said it wouldn’t be the first time the Army Corps underestimated the environmental impact of a project.

“(Mill Cove) is a sad example of how these underestimated impacts really devastate an ecosystem,” Rinaman said. “A once thriving cove is now just barely usable for recreational purposes.”

‘Hell of a way to grow up’

Carlton Higginbotham, 74, spent the early years of his childhood on the banks of Mill Cove, swimming among alligators, herding manatees like a cowboy and catching plenty of fish.

“We were a bunch of crackers,” he said. “It was a hell of way to grow up, let me tell you. Huckleberry Finn, I mean literally.”

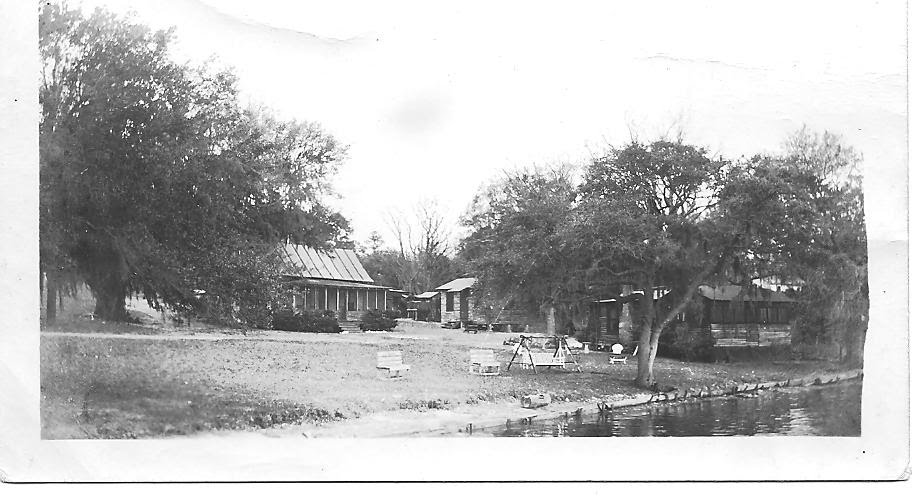

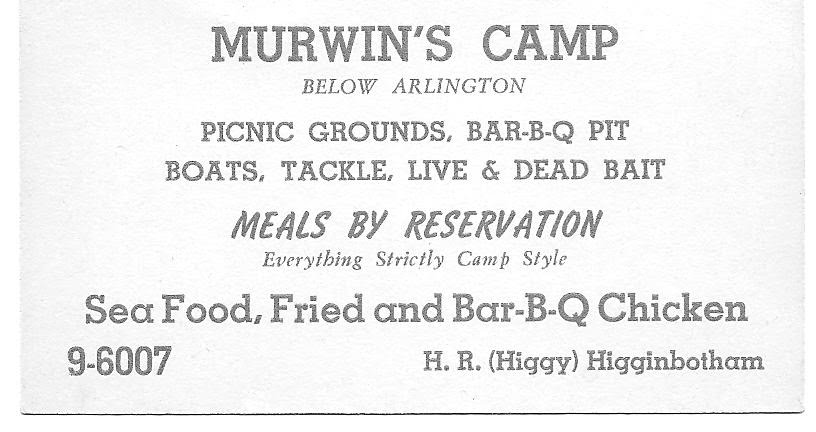

His family owned Murwin’s Camp, a long-defunct fish camp located near what is now Colony Cove. Lured by the cove’s remoteness and fruitful fishing, guests rented cabins and launched boats into deep water right off the bank.

Around the time Higginbotham turned 6, the Army Corps completed a project that forever changed the face of the St. Johns River.

Up until that time, the river was hardly an ideal course for cargo ships. While the Army Corps had successfully dredged a deepwater shipping channel, captains had to carefully navigate a series of sharp, dangerous turns as they passed Dames Point and Mill Cove.

Convinced a safer and shorter route between the port and Atlantic Ocean would increase cargo traffic and grow Jacksonville’s economy, city officials hired the Army Corps to create an improved version of the river.

The Army Corps dug through more than a mile of dry land to forge a new channel, which they named the Fulton Cutoff.To train the flow of the river into their new channel, engineers separated Mill Cove from the rest of the river by expanding an existing island with dredging spoils and built underwater dams at the cove's two entrances to impede water from coming in.

The project was a success, creating a straighter shipping channel and shortening the distance between the port and ocean by nearly two miles.

Shortly after the project was completed, patches of mud began staining Mill Cove’s white sand beaches, said Bob Sikes, who grew up fishing and shrimping on the cove.

Sikes’ roots in Mill Cove are deep: he is the great-great-grandson of Archibald Gilmore, an Irish-born fisherman who was one of the area’s original settlers.

The invasion of mud that Sikes witnessed marked the beginning of the end for old Mill Cove. Without the strong flow of the river to flush it clean, the cove began to fill with mud and sand, and the water became shallower.

Sikes, 79, said it was easy to catch more than a dozen fish in an hour when he was a young boy. But as he grew older and the cove shallower and more polluted, he said people lost interest in fishing there.

“It got to the point where it wasn't even worth going down. Hell, you were in the mud… At low tide, you couldn’t get your boat out,” Sykes said. “It was just a slow death is what it amounted to.”

‘Stagnant mudhole’

The changes to Mill Cove were noticeable to everyone by the late 1960s.

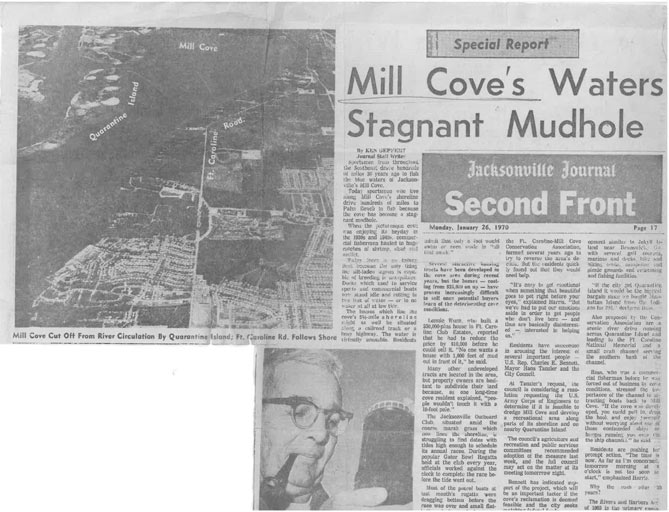

On January 26, 1970, the Jacksonville Journal ran an article about the troubles in Mill Cove with the headline: “Mill Cove’s Waters Stagnant Mudhole.”

The story reported that the once-booming commercial fishing fleet had entirely abandoned Mill Cove. The Jacksonville Outboard Club was struggling to schedule its annual boat races on days with tides high enough to allow safe navigation. (The club would shutter for good in the 1980's and sell its Arlington headquarters to residential developers.)

The once deep water behind homes was receding, leaving residents stuck with unusable docks and property that wasn’t quite waterfront anymore.

“No one wants a house with a thousand feet of mud out in front of it,” said resident Lonnie Wurn in the article, explaining how he had to drop the price of his “$50,000-plus home” by $10,000 in order to sell it.

The public outcry grabbed the attention of local leaders, and Mill Cove’s restoration became a hot-button political issue that lingered for the next three decades.

The Army Corps accepted fault for Mill Cove silting in and spent years looking for a solution. By 1981, engineers formulated a plan to dredge more than a million cubic yards of sediment and dig a new channel to flush the cove clean.

U.S. Rep. Charlie Bennett, who began his efforts to restore the cove in 1974, led the charge in Washington to get the millions of dollars needed to pay for the project. However, Bennett encountered a particularly tight fist in the Capitol.

The project struggled to gain support from President Ronald Reagan’s administration, which was frustrated with the city’s reluctance to commit its own money to the restoration. It was a tough time to get money for waterway projects, and the project was cut from the federal budget several years in a row as politicians bitterly fought for their own pet projects.

“It’s the slowest project I’ve ever had,” Bennett told the Jacksonville Journal in September 1984, a month before Congress cut the project from the budget as it faced a veto from Reagan.

Bennett finally landed a victory when Reagan signed legislation in 1986 that set aside $4 million for the restoration. After 15 years of fighting, residents and local leaders had fresh optimism about restoring the cove to its former glory.

In 1988, the Army Corps finished dredging the cove and clearing the east and west entrances to the river to allow in its cleansing current.

The Army Corps surveyed Mill Cove shortly after it completed the project. While engineers said it would take years to determine whether the project would permanently deepen the cove, they found water in some areas had already grown deeper.

However, some residents weren’t happy and said the water had become even shallower in other areas. The Army Corps survey confirmed their observations, finding the project caused some areas to further silt in.

Other residents questioned why boat access had not improved on the southern end of the cove, where most homes are located. While the Army Corps initially planned to dredge a boating channel near the southern shore, residents learned it was dropped from the project because the goal was to improve water flow, not boating access.

‘Little progress is made’

Several years after the dredging, little improvement had been made in the cove.

“The periodic surveys indicate material is moving around in Mill Cove, but it’s so minute, it’s hard to tell which direction,” said Gordon Holmes, a chief with the Army Corps, in a March 1991 story in the Times-Union. “Material is building up in spots. Sandbars are coming and going.”

By 1995, Arlington residents were again holding community meetings demanding more work to deepen the cove. This time, they wanted the boating channel on the south end of the cove.

The state and federal government eventually agreed to split the costs of a $2 million project. In 2002, engineers began dredging a 6-foot deep, 80-foot wide channel from Reddie Point to the eastern entrance of the cove.

In addition to providing deep water for boats, engineers hoped the channel would bring in enough water flow to stop the cove from silting in and even flush out existing layers of mud.

The Army Corps completed the project in the early 2000's, and it would be the last attempt to restore Mill Cove.

The navigation channel, which still exists today, improved boating access in some areas. Beyond that, Mill Cove mostly remained the same.

“There’s not enough water volume (to flush it out),” said Quinton White, a marine biologist and professor at Jacksonville University. “There was a lot of optimism among a lot of people. There was a group, even then, that said this was not going to work. We didn’t get a lot of press coverage at the time.”

Still, these days are better ones for the cove compared to 30 years ago. Anglers catch plenty of redfish, sea trout and flounder around Mill Cove's submerged grass and oyster bars. In the summer, the cove even gives up the occasional tarpon.

The oysters and grass are signs of a biological transformation unfolding: Mill cove has been slowly turning into a salt marsh since the Army Corps completed its fateful project in the 1950's, White said. If left alone, White said, most of the cove will completely fill in with mud and transform into a sea of green spartina grass.

In a state that has lost countless acres of marshland to development, White sees a certain beauty in a new marsh being born from another man-made environmental blunder.

“It’s amazing what nature will do sometimes to correct the mistakes we make,” he said. “Nature is amazingly resilient.”

About the reporters

Nate Monroe has covered City Hall at the Florida Times-Union since 2013, following reporting stints at the Pensacola News Journal in the Panhandle and the Daily Comet in Thibodaux, La.

Christopher Hong has covered City Hall at the Florida Times-Union since 2013. Previously, he was a reporter at the Citizens' Voice in Wilkes-Barre, Pa.

About this project

Times-Union reporters Nate Monroe and Christopher Hong spent months reviewing historical documents and data, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers reports, court records, City Hall documents, and interviewed researchers and legal experts. That work led to one unmistakable conclusion: A century of dredging and engineering has turned the once-lazy St. Johns River into a waterway that more resembles the Atlantic Ocean than at any other time in its past. The river on our doorstep has saltier water, faster currents, and tides that come earlier and are more extreme. In a major storm, dredging may have also led to more intense storm surge for neighborhoods that are even miles upriver. City leaders were blind to those risks.

Web design by Derek Hembd

Video footage shot by Michael Jones.

Special thanks to The Jacksonville Historical Society, whose archival records were invaluable; Chuck Meide for his article, "The Lost French Fleet of 1565: Collision of Empires," from which this report used information; Stefan Talke and Ramin Familkhalili at Portland State University, whose research was integral to this story; and many others quoted and not quoted in this story who were generous with their time and expertise.